What was a bitter George Pickett thinking when he ordered the hanging of Union prisoners at Kinston, N.C., in 1864?

On a raw mid-February day in 1864, two brigades of Confederate soldiers stood at attention around a makeshift gallows. They had been formed up to witness the deaths of 13 Union prisoners. Following the reading of the execution order, a signal was given and the platform upon which the bound and hooded Yankees stood dropped away. The deed sent shockwaves across the North and sections of the South, as well as calls for a reckoning against the hangings’ perpetrator that outlasted the war itself. This, however, was not the first execution of Union prisoners to be ordered that month by Confederate Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett. Nor would it be the last.

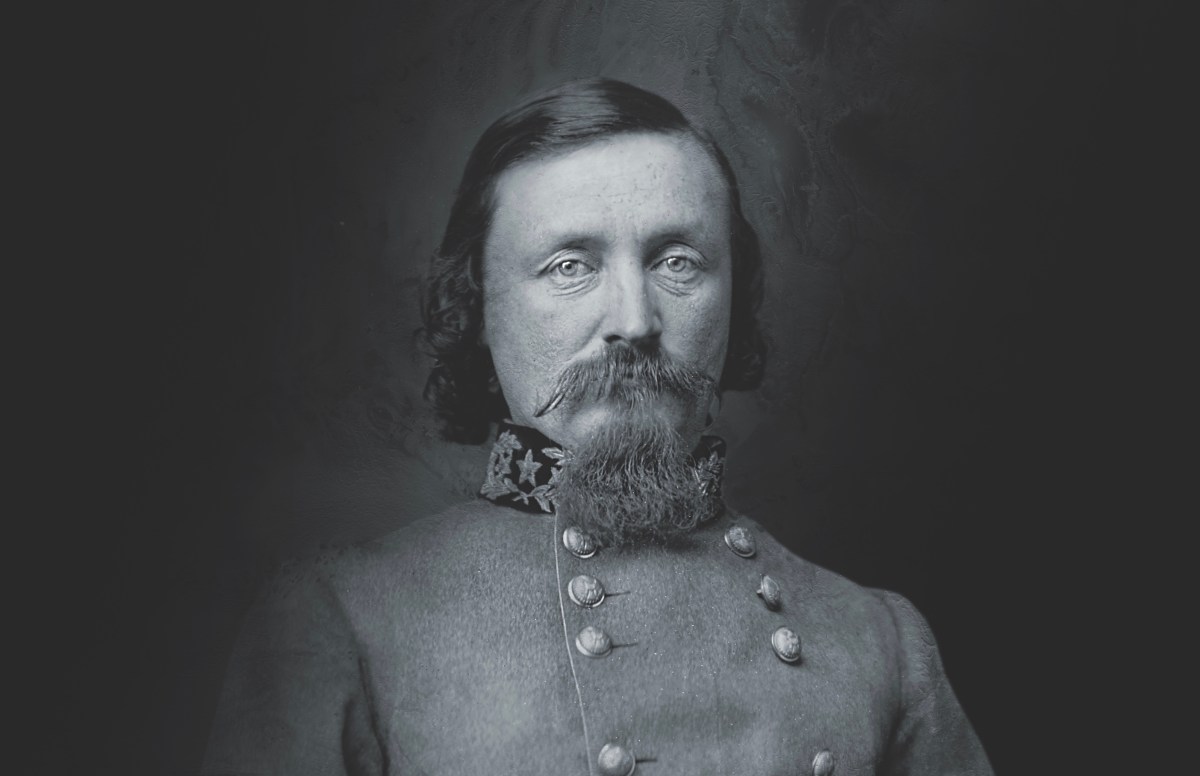

Throughout the war, the charming, foppishly vain Virginia aristocrat, who had famously finished last among an elite class of 59 cadets at the U.S. Military Academy in 1846, had been neither the brightest nor the most inspired of the South’s generals. Typically, Pickett’s inflated self-opinion had far outstripped reality; however, since the doomed July 3, 1863, charge at Gettysburg for which he is best remembered——the Confederates’ bloody frontal assault on Cemetery Ridge known as Pickett’s Charge—the general was clearly a changed man.

The order for that decisive Gettysburg assault had come not from Pickett but from the storied commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, General Robert E. Lee. Nevertheless, Pickett watched in helpless frustration, tears coursing down his cheeks, as nearly 9,000 troops from his own and two other Confederate divisions fell before the Yankee guns or were rounded up as POWs, marking the bitter conclusion to Lee’s second Northern invasion and presaging the South’s eventual defeat in 1865. It was a disconsolate, vengeful Pickett who retired from the field that day, replying with acrimony to Lee’s post-charge order to “rally” his division in case of a Union counterattack: “General, I have no division!”

After Gettysburg, Pickett was given command of the Department of North Carolina. It proved an impossible assignment. North Carolina had been a problem state for the Confederacy from the opening of hostilities. Unlike its sister state to the immediate south, which was the first to sever ties with the Union, North Carolina was the second to last to secede. From the beginning, its citizens had manifested mixed loyalties, and it remained so throughout the war. While some were staunch supporters of the Confederacy, others remained true to the Union. And many eschewed either cause, simply wishing to be left alone to tend to their hardscrabble farms. As historian Gerard A. Patterson wrote in Justice or Atrocity? General George E. Pickett and the Kinston, N.C. Hangings, “Whatever sectional discord existed between Northern and Southern states could in no discernible way relate to their own base and secluded existence. If they recognized any responsibility, it was to use whatever common sense they possessed to find ways to avoid being taken away from their bare board, ramshackle homes and near-worthless acres….”

Desertion in the ranks was a problem that bedeviled the Confederacy throughout the war. It only grew worse as the years of conflict passed, and various chroniclers have stated that the men of North Carolina headed the list. Soldiers “took leg bail” for a variety of reasons. Some had, in fact, long been loyal Southern soldiers. According to Michael Thomas Smith’s 2006 study, “Civil War Desertion”:“More than half the state’s deserters had served in the army for more than 18 months and almost 70 percent for more than a year. These men apparently felt a greater loyalty to their families, who desperately needed their assistance, or perhaps they recognized the futility of the Confederate cause, particularly in the last, hopeless days of the war.”

As the war progressed, Patterson wrote, some North Carolina soldiers “were deserting by squads and companies.” Some had been conscripted into the army against their will, either from their farms or out of local home guards and felt no particular drive to fight for the Confederacy. And when the chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that conscription was illegal, many draftees felt justified in quitting the ranks.

North Carolina was bleeding from other wounds besides desertion. A number of its coastal towns, vulnerable to Union naval power, had come under Federal occupation, and marauding Yankees—as well as organized bands of Rebel deserters—burned and pillaged at will.

Meanwhile, George Pickett was comfortably ensconced in his Petersburg, Va., headquarters with his new, young bride. (LaSalle Corbell Pickett, or “Sallie,” was 20 in 1863 when she married the 38-year-old George Pickett.) Given his limited resources—he frequently complained to Confederate officials in Richmond that he lacked sufficient forces to control so large and unquiet a region—Pickett was facing a challenge that would have daunted even the best of the Confederacy’s general staff, and his tenure in North Carolina was predictably ineffectual.

In January 1864, Robert E. Lee placed Pickett in charge of a major campaign. The coastal North Carolina town of New Bern had been under Union control since early 1862, with the Yankees well secured behind forts, blockhouses, and earthworks. Desperately in need of supplies, Lee determined that he could provision his army with the plentiful stores stockpiled in the town. George Pickett was given command of the combined land-and-sea expedition to recapture New Bern.

Using the town of Kinston as a staging area, Pickett led some 13,000 men—the largest force he personally had ever commanded—southeast toward New Bern. Eventually, nearly every aspect of the complicated plan went horribly awry, and the attack proved to be disastrous. Pickett’s attempt at redemption had resulted in yet another humiliating defeat, and although he tried desperately to shift responsibility onto his subordinates, this time the blame sat squarely on his own shoulders.

Over the next weeks, as word of the New Bern debacle spread, both Northern and Southern newspapers pilloried the hapless general. Worse yet, President Jefferson Davis himself was painfully aware of Pickett’s failure, writing in frustration to Lee, “General Pickett has returned from his expedition unsuccessful in the main object.”

In a drenching rain, an angry, despondent Pickett led his army the 35 muddy miles back to Kinston. The only positive result of the entire endeavor had been the capture of nearly 500 Yankee officers and men. As it turned out, most of the soldiers were native sons, a large number of them currently serving in the Union’s 2nd North Carolina. Several men had served in a home guard that had been forcibly absorbed into the Confederate Army. Its members had been given the choice of enlisting in the regular Confederate Army or being conscripted and, feeling no allegiance to the Confederacy, a number of them had simply “gone over” to the Union forces at the first opportunity.

Some of their own comrades, in an effort to cadge leniency from Confederate commanders, identified these men by name, pointing them out to their captors. One of Pickett’s lieutenants recognized two of the prisoners—Joe Haskett and David Jones—as soldiers who had formerly served under him in the 10th North Carolina.

Seething from his most recent disaster, and shamed by yet another blow to his reputation, Pickett detested deserters and refused to make distinctions. As Patterson pointed out, “Though his own dedication to duty frequently lapsed, he became a man virtually obsessed with the punishment of desertion regardless of motivation.”

Uncivilized Warfare

During the Civil War, as in most conflicts, it was accepted by both sides that desertion was punishable by death. Combatants captured in uniform, however, were generally accorded treatment commensurate with the rules of war. In the case of the Kinston prisoners, these disparate circumstances seemed to collide, leaving the men’s fate open to interpretation by their captors.

George E. Pickett, and the anonymous officers of what was in effect a kangaroo court, labeled the captives as traitors. This in itself is ironic, considering that Pickett—indeed, most of the general officers in the Confederate forces—had originally sworn an oath of loyalty to the very country against which they were now in rebellion. Some historians have, in fact, maintained that the very foundation of the Confederacy was laid on a single, massive act of treason, and that those responsible for perpetuating it could very well have shared the fate of the unfortunate Yankees at Kinston.

Perhaps the greatest irony as it pertains to the Kinston affair is that Pickett personally owed his military career to the commander-in-chief of the enemy forces. As a young man, Pickett sought acceptance as a cadet at West Point, only to discover that his state’s admissions quota had already been filled. He appealed to his uncle—an Illinois attorney—for help, whereupon the uncle’s associate, a young lawyer named Abraham Lincoln, persuaded a congressional representative to bend the rules and admit young George Pickett.

A further disgrace with Pickett’s execution of his prisoners was the manner in which he did so. Sarcastically thanking General John Peck for inadvertently providing him a convenient death list ran counter to all tenets of accepted military behavior, especially among officers. The total denial of counsel for the prisoners, the rough treatment accorded them both before and during their executions, and the callous way in which their bodies were disposed of, bespeaks a man who had gone beyond the limits of custom and courtesy, and who had given unbridled license to his thirst for vengeance. In the end, the scented hair, the frilly shirts, lace-trimmed uniforms, and high-born Virginia manners—what one soldier scornfully described as his “efforts at aristocratic airs”—proved little more than shallow affectations, masking Pickett’s own inadequacy as both an officer and a man of character.

Observed one expert: “In North Carolina, he lost all sense of restraint and exhibited the very behavior he thought only the enemy capable of practicing: uncivilized warfare.” –R.S.

In his fury, Pickett viewed all North Carolinians in blue uniforms as traitors; but he reserved his greatest contempt for those he believed had traded the gray for the blue. After his rain- and mud-soaked troops camped for the night on their retreat from New Bern, Pickett vented his spleen on the two soldiers his lieutenant had pointed out. “Goddamn you,” he thundered, “I’ll have you shot, and all other damned rascals who desert!”

Turning to two of his generals, he stated, “We’ll have to have a court martial on these fellows pretty soon, and after some are shot the rest will stop deserting.”

Dozens of the prisoners were crammed into Kinston’s cold, dungeon-like jail, where they were given a single hardtack cracker a day and denied bedding. The more fortunate had friends and relatives close enough to supplement their meager diets and provide them with blankets.

Pickett wasted little time on formal hearings. Immediately upon arriving back in Kinston, he convened a court-martial for Haskett and Jones. It was a mere formality, the verdicts and sentences a forgone conclusion. Even before the court’s findings were announced, a crew of soldiers was hard at work hammering together a gallows behind the jail, while an officer scoured the town for sufficient lengths of rope.

The court swiftly finished its business, and without preamble, the two men were led from the jail, placed in a wagon, and conveyed to the roughhewn structure. All the soldiers in the vicinity—two entire brigades—had been turned out to witness the executions. A young lieutenant read the charges—“desertion and taking up arms for the enemy”—and the fatal verdict of the court. Among the observers were several officers “who had received their training at the U.S. Military Academy. They had themselves once sworn a solemn oath of allegiance to the same flag these men had ultimately embraced.”

The hangman in the initial smaller procedures was a private of the 10th North Carolina who had been randomly ordered to perform the task, and who had been friends with the condemned. Since the customary black hoods could not be found, the doomed men’s heads were covered with rough corn sacks.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. John J. Peck, Pickett’s Union counterpart, began an exchange of letters with Pickett that would later come back to haunt the Confederate general. Having read a newspaper account of the earlier hanging of a black Union soldier at Pickett’s order, Peck wrote Pickett, reminding him of the rules of war and stating that he would execute a Rebel prisoner for every man in blue Pickett hanged. Pickett defiantly responded that he had “in my hands…some 450 officers and men of the U.S. Army, and for every man you hang I will hang ten….”

An alarmed Peck, realizing that Pickett was holding the men of the 2nd North Carolina, sent another missive, pleading for their lives. Unfortunately, he did a foolish thing, one that he would regret for the rest of his life. In his letter, he listed, by name, 53 of the former Confederate soldiers in the Union 2nd North Carolina who had switched sides, asking that Pickett accord them the same courtesy as he would all other prisoners of war. Shortly thereafter, he read of the executions of Haskett and Jones and wrote yet again, redoubling his request that his men be properly treated.

Correspondence between combatants in the field was understandably slow, and by the time Peck’s letter reached Pickett, it was too late. Nor would it have mattered.

Pickett’s response to Peck’s most recent letter is a study in sarcasm and malevolence, and refers to the “list…which you have so kindly furnished me, and which will enable me to bring to justice many who have up to this time escaped their just deserts [sic]. I herewith return you the names of those who have been tried and convicted by court-martial for desertion from the Confederate service.…They have been duly executed according to law and the custom of war.”

Pickett ended with, “Extending to you my thanks for your opportune list, I remain, very respectfully, your obedient servant.” Soon thereafter, Pickett reiterated his threat to hang 10 Yankees for every Rebel the North executed—and few now doubted his brutal sincerity.

Peck’s rage over both the executions and Pickett’s threat to hang more prisoners is evident in every line of his subsequent reply. Pickett’s “announcement,” he writes in part, “evinces a most extraordinary thirst for life and blood.…Such violent and revengeful acts, resorted to as a show of strength, are the best evidences of the weak and crumbling condition of the Confederacy….”

Pickett had acted swiftly, consulting neither Robert E. Lee nor his corps commander, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. Within two weeks of his return to Kinston, his seven-man military court, which acted anonymously, kept no trial transcripts and allowed no defense counsel for the accused, had condemned 22 men in three separate sessions. With the exception of Haskett and Jones, they had all been members of the local home guard that had been conscripted into the Confederate Army. At least one of these was little more than a child. The March 11 issue of the Philadelphia Inquirer stated, “Ira Neal, a drummer boy, fifteen years old, who had never been in the Rebel service, was among the number hung at Kinston….” One man was so physically deformed that he had to “drag himself along behind the others to the gallows.”

The largest of the three doomed groups consisted of 13 men, and the means of their demise required special modifications, the original two-man gallows having been determined to be inadequate. Therefore, a massive scaffold was built, capable of dispensing all 13 at once. This time, the hangman was a local civilian, who had sought the position in exchange for a fee and the dead men’s clothes, proclaiming that he would “do anything for money.”

The night before their execution was heart-wrenching. The chaplain assigned to comfort the men in their dungeon, the Rev. John Paris of the 54th North Carolina, wrote, “The scene beggars all description….Here was a wife to say farewell to a husband forever. Here a mother to take the last look at her ruined son; and then a sister who had come to embrace, for the last time, the brother who had brought disgrace upon the very name she bore by his treason to his country.”

After each round of hangings, the bodies were stripped and left to lie naked at the foot of the gallows. Many were local men whose families claimed their bodies. Those who went unclaimed were unceremoniously buried in a mass grave in the sand near the looming instrument of their deaths.

One of the stated objectives of the New Bern Campaign had been the capture of deserters; in this alone, Pickett was successful. Ironically, what he could not foresee was the fact that his ignominious defeat at New Bern and subsequent treatment of his prisoners, far from discouraging further desertions, would impel increasing numbers of disheartened soldiers to escape from the Rebel army, and into the Union ranks. As a newspaper correspondent observed, “[T]he cruel massacre…is causing desertions from the Confederate service by the wholesale, and creating an indignation which, it is feared, will be uncontrollable.” Wrote Patterson, “[T]he

cost of his excessive punishment was to disgust his own men and horrify the civilian population.”

Ironically, as the war was nearing its end, one of the worst records for desertion was held by Pickett’s own division. His men generally disliked him, considering him an arrogant, vainglorious martinet, and discipline within the division was poor. In a 10-day period alone, 512 of his men quit the ranks, as compared with single- and double-digit desertions in the other divisions.

Pickett’s last major command was at the April 1, 1865, Battle of Five Forks, Va. It proved as decisive a disaster as had the ill-fated charge at Gettysburg and his New Bern debacle. Five Forks was a crossroads that lay only a few miles from the Southside Railroad, the Confederacy’s last working supply line, and Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had sent Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan to cut it. Ostensibly, this would end the nine-and-a-half-month siege of Petersburg, force the evacuation of Richmond, and potentially bring the war to a rapid conclusion.

The railroad was vital to the Confederacy’s survival, and Lee ordered Pickett to “hold Five Forks at all hazards.” Lee’s urgency apparently failed to register with his subordinate. At the moment Sheridan’s forces attacked, Pickett was nowhere to be seen. He was, in fact, two miles to the rear, attending an impromptu shad bake with some of his fellow generals who failed to hear any sounds of the ongoing battle. As Pickett biographer Lesley J. Gordon states, “Completely losing all sense of the importance of his responsibilities, Pickett left the field….While he ate fish and perhaps drank whiskey, Pickett ignored repeated reports of the enemy advance. Several officers did not even know that Pickett had left the front, nor his location.”

By the time he returned, the battle was all but lost. The fallout was stunning. The Confederates lost nearly four times the number of casualties as the Yankees, with a large number of the Rebels taken prisoner. The Siege of Petersburg was indeed lifted, and the next day Lee informed President Davis that both Petersburg and Richmond had to be evacuated. On April 9, Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. In those final days, Lee spotted Pickett, who had been removed from command after the Five Forks debacle. According to Colonel John Singleton Mosby, quoting Lee’s aide-de-camp Charles S. Venable, Lee asked with disgust, “Is that man still with this army?”

Shortly after Lee’s surrender, Pickett discovered that his actions at Kinston had not been forgotten when two old friends in the Union Army alerted him that he was being sought by federal authorities to face war crime charges. In the words of Pickett’s wife, they advised him to “absent himself for a while until calm reflection should take the place of wild impulse.”

It was sound advice; a court of inquiry was convened in October 1865, to investigate the “murder of Union soldiers.” The tribunal called several witnesses, including widows of the executed soldiers, who testified that their husbands had been coerced into the Confederate service under threat of arms. They further stated that while their husbands were incarcerated, Rebel patrols visited their homes and systematically stripped them of their goods, livestock, and winter provisions.

The tribunal found that the victims had been forcibly conscripted from their local home guard, an action that the state’s highest court had declared to be illegal, and technically they “had never been Confederate soldiers.…Therefore, a Confederate state court martial had no jurisdiction over them.” They recommended that Pickett be brought before a military commission for trial, under Brig. Gen. Joseph Holt, the Union Army judge advocate.

In his deliberations, Holt, as director of the Bureau of Military Justice, supported the board of inquiry’s opinion that the Kinston victims had never voluntarily served the Rebellion. “Submission to that service,” he wrote, “was, in itself, a crime from which it was their bounden duty, as men and as patriots, to flee at the first opportunity.”

When Holt read the letters between Pickett and Peck, he was livid, writing Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that Pickett’s “imperious and vaunting temper” showed “his readiness to commit this or any kindred atrocity.” Holt further determined that “the rebel Major General G.E. Pickett…was the guilty party…by whose order these sufferers were arrested and prosecuted, and by whose order executed.”

The board agreed: “While other prominent rebels seem to have been concerned in these shameful transactions as accessories, the evidence clearly shows that General Pickett was the prominent authority under whose direction…the murder of our soldiers took place.” On December 30, 1865, he ordered Pickett’s immediate arrest.

The order proved impossible to carry out. By now, a terrified Pickett had gathered his wife and newborn son and escaped to Montreal, where he was living under an assumed name, surviving on borrowed money and his wife’s salary as a Latin teacher. To further mask his identity, he cut his trademark perfumed locks, so long a source of pride.

Efforts by well-connected friends—many of whom were fellow West Point graduates and old U.S. Army buddies, and who were willing to overlook the Kinston affair as a mere lapse in judgment—failed to move President Andrew Johnson to overlook Pickett’s alleged offenses. Ultimately, however, Ulysses S. Grant, an old comrade of Pickett’s from their Mexican War days, interceded with Johnson on the fugitive’s behalf. Pickett returned to Virginia, and in June 1866 took the oath of allegiance to the Union.

Life was not kind to the repatriated Pickett. His health, which had suffered badly late in the war, had worsened significantly in exile. Prior to Lee’s surrender, Union troops under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler had burned down Pickett’s ancestral Virginia home, possibly in retaliation for Kinston. Now, Pickett and his family were forced to live in a nearby cottage. He made a half-hearted attempt at farming, but proved “singularly inept,” as Patterson writes. Finally, he became a salesman for the Virginia branch of New York’s Washington Life Insurance, a job that bored him, and at which he enjoyed only middling success.

George Pickett had always been a heavy drinker, which well might be the reason, in August 1875, his liver failed him. He died a bitter, broken man at age 50, leaving his 32-year old widow to defend—and in many instances, invent—his wartime experiences.

Ron Soodalter, who writes from Cold Spring, N.Y., is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader.