As a housekeeper for the German Embassy in Paris, Marie Bastian had two tasks. She was expected to gather the day’s paper trash twice a week…unless she recognized something worth pocketing to pass to her other employer, Maj. Hubert-Joseph Henry of the Section de Statistiques (“statistics section,” the innocuous-sounding title for French counterintelligence). Making her rounds on Sept. 26, 1894, she noticed a handwritten note in French lying torn up in the wastebasket of German military attaché Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen. She wasted no time in taking it to Henry, who passed it to his superior, Lt. Col. Jean Sandherr.

Pieced together, it proved to have only minor military secrets. Far more serious was the evidence of its origin. Someone in the French General Staff was passing secrets to the Germans.

A Spy In Their Midst

It had been 23 years since the Franco-Prussian War, in which the Second Empire of Napoleon III collapsed and the collection of kingdoms and duchies that brought it down united into a single entity called Germany. Peace had reigned since then between the French Third Republic and the German Second Reich, but each power eyed the other suspiciously.

Behind a seeming high point in European civilization, spy games went on as secret agents from all the powers sought out any foreign secrets that might give them an edge, should another war ever break out. Although the French army had recovered from its humiliating defeat, it remained insecure to the brink of paranoia. This new revelation seemed to suggest that the paranoia was warranted.

Sandherr had been aware that someone was leaking information to Schwartzkoppen, but the note was the first solid evidence to fall into his hands. Matching the handwriting against documents among the General Staff, he found at least two specimens that seemed to match. Since the intelligence being passed was a list of new artillery components, including technical details for a hydraulic brake in a new 120mm howitzer and modifications to artillery formations, Sandherr narrowed the search down to an artillery captain on the staff: Alfred Dreyfus.

Soldier and Patriot

A thorough examination of Dreyfus suggested dubious spy material. Born on Oct. 9, 1859 in Mulhouse, Alsace, he was the youngest of nine children whose father had risen from a street peddler to a textile manufacturer. When the Germans seized Alsace and Lorraine in 1871, the Dreyfus family moved to Basel, Switzerland, then to Paris. There Alfred chose to pursue a career in the army, enrolling in the Ecole Polytechnique to study military sciences.

In 1880 he was commissioned a sub-lieutenant and from then until 1882 studied artillery at Fontainebleau before being assigned to the 31st Artillery Regiment at Le Mans and then the 1st Mounted Artillery Battery of the First Cavalry Division in Paris. In 1885 he was promoted to full lieutenant and in 1889 served as adjutant to the director of the Etablissement de Bourges with the rank of captain.

Dreyfus married Lucie Eugènie Hadamard on April 18, 1891. Three days later he was admitted into the Ecole Superieure de Guerre (war college), from which he graduated ninth in his class in 1893. He was assigned to the headquarters of the Army General Staff—and ran into the first serious career obstacle stemming from his being the only Jewish officer on the staff.

One of his evaluators, Gen. Pierre de Bonnefond, gave him high marks for his technical acumen but lowered his overall score with a zero rating for “likeability” (what in modern U.S. Army jargon amounted to an “attitude problem”), adding that “Jews were not desired” on his staff. Although admitted to the staff, Dreyfus and some supporters protested Bonnefond’s blatant bias—an act that would be used against him when he came under investigation.

Dreyfus Framed

Recommended for you

Despite two of three examiners expressing doubts as to the similarity between Dreyfus’ writing samples and the handwriting on the note, Sandherr made it the cornerstone of his evidence against the captain. On Oct. 15, Dreyfus was ordered to appear at work in civilian clothes and was questioned by a self-styled handwriting expert, Maj. Armand du Paty de Clam, who, feigning an injured hand, asked Dreyfus to write a letter for him. Dreyfus did, giving no indication that he recognized the message he was transcribing as the same one to Schwartzkoppen. Upon his completing it, Du Paty fleetingly examined both documents and informed Dreyfus he was under arrest.

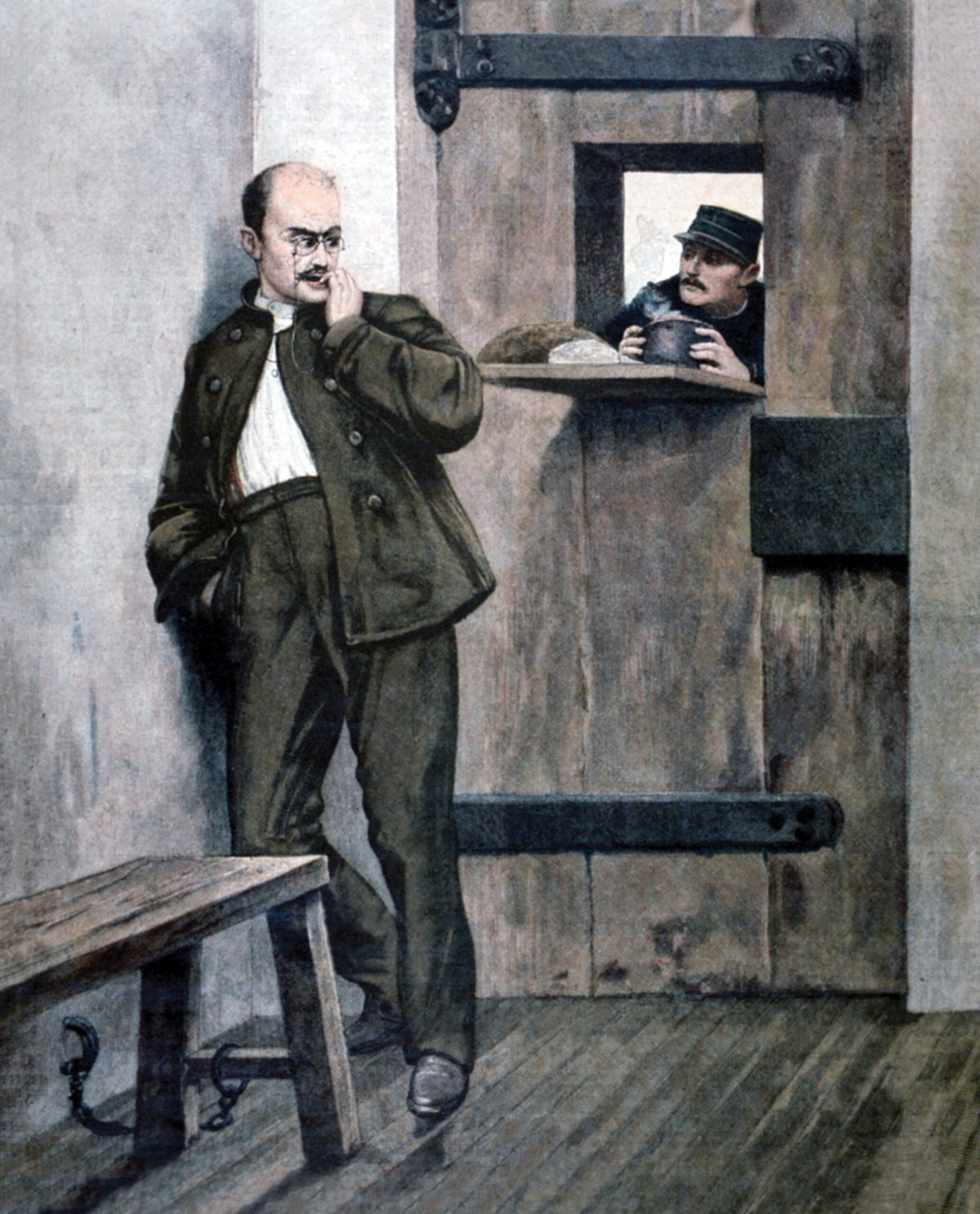

After four days of a secret court martial, Dreyfus was convicted of treason on Dec. 22 and sentenced to life imprisonment. At a public ceremony on Jan. 5, 1895, he was publicly stripped of every accoutrement on his uniform and had his sword broken before being sent to serve his life imprisonment at the penal colony on Devil’s Island in French Guiana. His last statement before being taken away was: “I swear that I am innocent. I remain worthy of serving in the army. Vive la France! Vive l’Armée!”

As Dreyfus was led away, he faced a barrage of insults, not only from brother officers but crowds stirred up by army provocateurs to undermine any sympathy for the traitor. The emphasis was on his religion, the most common cry being “Death to the Jews!” One Hungarian correspondent covering the event for the Austrian Neue Freie Presse took special notice.

Although he then believed Dreyfus guilty, he commented on the nature of the aftermath in his diary in June 1895: “In Paris, as I have said, I achieved a freer attitude toward anti-Semitism…above all, I recognized the emptiness and futility of trying to ‘combat’ anti-Semitism.” Despairing of his co-religionists ever finding acceptance anywhere in Europe, Theodor Herzl turned his thoughts toward the idea of their finding a homeland of their own.

In Search of Justice

While Dreyfus endured heat, insects, malaria, dysentery and all the horrors that gave Devil’s Island its dreaded reputation, his older brother Mathieu spent all the time, energy and money at his disposal to have Alfred’s case reexamined, seemingly in vain. One appeal after another was rejected. The French army staff, obsessed with maintaining an image of infallibility, was not about to reconsider its rush to justice against the homegrown “foreigner” in its midst.

When Sandherr, promoted to colonel, left the Section de Statistiques to command the 20th Infantry Regiment at Montauban on July 1, 1895, his successor, Lt. Col. Marie-Georges Picquart, was instructed by Assistant Chief of the General Staff Charles-Arthur Gonse to find more incriminating evidence to ensure that Dreyfus stayed right where he was.

Picquart, however, proved to be of different moral fiber. Investigating more on his own than his superiors authorized, the more he found the less the case against Dreyfus rang true to him—especially in March 1896, when he found a telegram from Schwartzkoppen, intercepted before it left the embassy, addressed to the actual author of the note.

That and other handwritten documents revealed a more precise handwriting match than Dreyfus’s. The handwriting was traced to Maj. Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, another staff officer who had served in intelligence from 1877 to 1880. In a scenario common in the world of espionage, Esterhazy had fallen deeply in debt and sought a way out by selling secrets to the Germans. Confronted by Picquart on April 6, he made a full confession. Picquart submitted his revised report, with a recommendation that the Dreyfus case be reexamined.

A Military Cover-Up

The response was hardly what he expected. His demand ran into brick walls at every turn from senior officers like Chief of Staff Gen. Raoul le Mouton de Boisdeffre and Minister of War Gen. Auguste Mercier, who remained determined that army intelligence not be sullied with having to admit that a mistake led to a miscarriage of justice. In regard to letting the real traitor slip away, Gonse went so far as to say, “If you are silent, no one will know.” “What you say is abominable,” replied an outraged Picquart. “I refuse to carry this secret to my tomb.”

Picquart’s strong sense of justice led to his undergoing a series of transfers “in the interest of the service,” first to a unit in the French Alps and ultimately to command the 4th Tirailleurs Regiment in Sousse, Tunisia. In a further attempt to discredit his findings, Boisdeffre and Gonse ordered Picquart’s deputy in the Section de Statistiques, Maj. Henry, to fortify Dreyfus’ file with more incriminating evidence. This Henry did on Nov. 1 by producing what he declared to be further correspondence between Dreyfus and the Germans. However, when Boisdeffre and Gonse brought the most incriminating letter to then-Minister of War Jean-Baptiste Billot, they realized that it was a forgery clumsily created by Henry himself.

Dreyfus’ innocence was becoming too clear to deny. Yet Billot joined Boisdeffre and Gonse in agreeing that the verdict must stand—and to persecute Picquart, “who did not understand anything.” Henry conjured up an embezzlement charge against his former superior and sent him an accusatory letter. This only brought Picquart back to Paris, armed with a lawyer.

Far from being buried, by mid-1896 the Dreyfus case had grown into a cause célèbre attracting partisans on both sides. Most French journals upheld the guilty verdict and opposed a retrial, reinforcing their arguments with accusations that Jews could only be expected to betray any country they inhabited.

Besides the army, the partisans who came to be called “anti-Dreyfusards” were mainly conservatives, nationalists and traditionalists. The tradition they conserved was hundreds of years of antisemitism that had supposedly ended with the Revolution and the Rights of Man, but which the General Staff tacitly encouraged in its ongoing campaign to keep the brand of traitor on Dreyfus. Among the foremost civilian mouthpieces was Edouard Drumont, whose publication La Libre Parole became an open forum for anyone with bile against Jews in general.

The Spy Escapes

In spite of all this, a growing cross-section of the French intelligentsia began taking up Dreyfus’ case. The first of these “Dreyfusards” was anarchist journalist Bernard Lazare, who after examining the existing evidence published an appeal from Brussels, Belgium. The conflict between of the Revolution’s ideals and the revival of old prejudices in “defense” of a Catholic France came to virtually split the entire country in two, breaking up lifelong friendships even in the world of impressionist art. Claude Monet, Mary Cassatt, Paul Signac and Camille Pisarro, for example, were Dreyfusards, while Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were anti-Dreyfusards.

With evidence of Esterhazy’s guilt and Dreyfus’ innocence leaking into public scrutiny, the General Staff took a new step to address the matter head-on. On Jan. 10, 1898, it tried Esterhazy before a closed military court, Mathieu and Lucie Dreyfus’ appeals for a civil trial having been denied. The three army-supplied “experts” testified that Esterhazy’s handwriting did not match that on the bordereau. The next day, after three minutes of deliberation, the court acquitted Esterhazy and all officers present cheered. Dreyfusards protested in the streets, to be beaten down by mobs of rioting anti-Dreyfusards and antisemites.

Dreyfus suffered on, but the trial’s real victim was Picquart, who was discredited, subsequently arrested for “violation of professional security” and imprisoned in Fort Mont Valérien.

Having been publicly exonerated, Esterhazy was discretely discharged from the army and exiled to Britain via Brussels. Settling in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, he lived out his life comfortably until 1923.

The Dreyfusards swiftly changed tactics, doubling down on Lazare’s use of the press with a vehement 4,500-word open letter to President Félix Faure by novelist and social critic Emile Zola in the Jan. 13, 1898 issue of the newspaper L’Aurore. It was aimed directly at the high command’s perfidy with a title suggested by fellow journalist Georges Clemenceau:“J’Accuse!”

Clemenceau himself was equally accusatory when he declared, “What irony is this, that men should have stormed the Bastille, guillotined the king and promoted a major revolution, only to discover in the end that it had become impossible to get a man tried in accordance with the law.” Others who took up Dreyfus’ cause included Léon Blum, Anatole France, Marcel Proust, Sarah Bernhardt and even Mark Twain.

A Forgery discovered

J’Accuse exposed all that was known of the army’s morally corrupt handling of both Dreyfus and Esterhazy and included the General Staff members involved by name. L’Aurore’s circulation was normally 30,000 but it sold 200,000 copies on Jan. 13. The anti-Dreyfusards’ reaction was so violently negative that Zola needed a police escort to walk to and from his home. On Jan. 15 Le Temps called for a new public review of Dreyfus’ case. Minister of War Billot struck back by filing a public complaint against Zola and Alexandre Perrenx, manager of l’Aurore, for defamation of a public authority, which was approved by the Chamber of Deputies by a vote of 312 to 22.

Held at the Assises du Seine between Feb. 7 to 23, the trial ended with Zola condemned to the maximum sentence, a year in prison and a 3,000-franc fine. Again, the verdict was accompanied by street riots against Zola and against Jews. After another trial on July 18, Zola took friends’ advice and exiled himself to England for the following year. In the process, so much of the Dreyfus Affair was exposed to public scrutiny that Zola’s two courtroom defeats ultimately amounted to a tide-turning victory.

France got a new minister of war, Godefroy Cavaignac, who was eager to prove Dreyfus’ guilt but was completely in the dark about the high command’s obstruction of justice. He ordered the case files examined and was astonished to find out how much evidence had been withheld from Dreyfus’ defense.

On Aug. 13, 1898 one of his staff, Louis Cuignet, holding a key document before a lamp, noticed that the head and foot were not the same paper as the body copy. The forgery was soon traced to Major—now promoted to lieutenant colonel—Henry.

A court of inquiry was called for Esterhazy, who admitted his treason and revealed the high command’s collusion in framing Dreyfus. On Aug. 30 the council questioned Henry in the presence of Generals Boisdeffre and Gonse. After an hour of interrogation from Cavaignac himself, Henry broke down and confessed to having falsified the evidence. He was promptly arrested and imprisoned in the Fort Mont Valérien. The next day he was found with his throat cut. Nobody found a straight razor on his person when he entered his cell. How it got there—and whether his death was suicide or murder—remains a mystery.

With the news reports of Henry’s act of deceit, the anti-Dreyfusards declared him a martyr. Lucie Dreyfus pressed for a retrial. Cavaignac still refused, but the president of the council, Henri Brisson, forced him to resign. Boisdeffre also resigned and Gonse was discredited. While the partisans continued to struggle, sometimes violently, new revelations were gradually shifting the political landscape. A growing number of French Republicans recognized the injustice that hid behind the military’s veneer of “patriotism.”

Pardoned?

On June 3, 1899, the Supreme Court overturned Dreyfus’ verdict and sentence. Dreyfus himself had little or no access to news of the maelstrom brewing in the wake of his arrest. It was days later that he learned that he was being summoned back to France.

On June 9 Dreyfus departed Devil’s Island—only to be arrested again on July 1 and imprisoned at Rennes, where he was to undergo his retrial. This began on Aug. 7, presided over by Gen. Mercier, who was still determined to maintain the guilty verdict, and attended by as much popular rancor as before. On Aug. 14 one of Dreyfus’ lawyers, Fernand Labori, was shot in the back by an assailant who was never identified. As the original case against him crumbled, the president of the council, Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau, sought a compromise.

Although five of the seven court members upheld the original verdict, on Sept. 9 Waldeck-Rousseau declared Dreyfus guilty of treason “with extenuating circumstances” and reduced his life sentence to 10 years. The next day Dreyfus appealed for another retrial. Eager to put the “affair” behind France, Waldeck-Rousseau offered a pardon. Exhausted from his time on Devil’s Island, Dreyfus accepted those terms on Sept. 19 and was released on Sept. 21. Still, being pardoned implies guilt. Dreyfus’ supporters remained unsatisfied with anything short of exoneration. Beyond France, protest marches broke out in 20 foreign capitals.

Not Guilty

Among other literary responses, Zola added to his previous essays, L’Affaire and J’Accuse! with a third, Verité (truth). On Sept. 29, 1902, however, Zola died, asphyxiated by chimney fumes from which his wife, Alexandrine, narrowly escaped. In 1953, the newspaper Liberation published the dying confession by a Paris roofer that he had blocked the chimney. Dreyfusards like socialist leader Jean Jaurès kept up the pressure for the next several years.

On April 7, 1903 Dreyfus’ case was investigated once more—and eventually its conclusion was finally reversed. On July 13, 1906 he was declared innocent. He accepted reinstatement in the army with the rank of major, backdated to July 10, 1903, and was also made a chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. He commanded the artillery depot at Fort Neuf de Vincennes until June 1907, when he retired into the Reserve. Also exonerated was Georges Picquart, who rejoined the ranks, was promoted to brigadier general and served as Minister of War from 1906 to 1909. He died in a riding accident on Jan. 19, 1914.

On June 4, 1908 Dreyfus found himself literally the target of residual antisemitic hatred. As he attended the transfer of Emile Zola’s ashes to the Pantheon, journalist Louis Grégory fired two revolver shots, slightly wounding him in the arm. Although apprehended, Grégory was acquitted in court.

The question of Dreyfus’ loyalty to his country got a final test when World War I broke out. Returning from the reserves at age 55, he commanded an artillery depot and a supply column in Paris but as the French army suffered heavy attrition in the field, in 1917 he transferred to take up an artillery command on the Western Front, fighting at Chemin des Dames and Verdun. His son, Pierre, also served as an artillery officer, being awarded the Croix de Guerre. Two nephews also became artillery officers but were both killed in action. The only other major player in the Dreyfus Affair to see combat during the war was Armand du Paty de Clam.

In 1919 Dreyfus’ honors were upgraded to Officier de la Légion d’Honneur. He died on July 12, 1935, aged 75, and was buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery. For all the French military’s efforts to make it go away, the Dreyfus Affair long outlived its namesake, leaving behind a number of political, legal and social aftereffects. In France it held up a mirror that showed two psyches—which would recur five years after Dreyfus’ death with new evocative names, such as Charles de Gaulle and Pierre Laval. Sadly, it still hasn’t gone away.