In a 1770 history of the Indies, French Jesuit Guillaime Raynal wrote, “Long distance voyages have given rise to a new species of nomad. I am referring to those men who travel to so many lands that they end up by belonging to none, who take wives where they find them, and take them only to satisfy their brute needs.” Raynal had in mind ambitious young fortune-seekers like Zephaniah Kingsley. Before he was 40, Kingsley, a roving merchant and slave trader, had sworn allegiance to the United States, Denmark, and Spain, meanwhile sometimes representing himself as a native of Mississippi or Louisiana. He fathered 9 children by four enslaved African women, one of whom was a 13-year-old from Senegal he purchased in Havana in 1806. Kingsley later would free and publicly acknowledge Anta Majigeen Ndaiye as his wife by the name Anna Kingsley, although the two never married. In Spanish Florida, where he ran vast plantations dependent on enslaved laborers, Kingsley came to recognize and champion a role for free Blacks as a moderating, power-sharing force for maintaining the stability of slavery. Unfolding on colonial Florida’s violent frontier, his story belongs to a paradoxical, pivotal chapter in the history of slavery in the United States.

Born in Bristol, England, in 1765 to a textile merchant, Zephaniah was 5 when his family emigrated to South Carolina. He saw the American Revolution result in his Tory father’s exile and steep financial losses. In 1793, Zephaniah, 28, swore allegiance to the United States in South Carolina. He became a globe-trotting opportunist, ranging as far as Zanzibar and Mozambique to deal in coffee, sugar, rum, and other goods, including human chattel. Returning from Africa he stopped on St. Thomas, a Danish holding in the Caribbean, where he pledged allegiance to Denmark. Kingsley bought a slaving vessel—perhaps hauling some 250 “new negroes”—and headed to Havana, Cuba, to do business. By 1803, he was appearing before authorities in St. Augustine, part of a Florida territory under Spanish dominion, to swear an oath to defend the province and obey the laws of Spain’s Catholic king. Among slaves he later brought to his Florida property was Anta, daughter of a captive Senegalese tribal leader.

Spain invited Kingsley and other white settlers to Florida to reinforce the population and help defend that Spanish holding against incursions by Native Americans and the British. In this northeast corner of Florida, gigantic plantations grew citrus, indigo, and rice under management by Kingsley and others. On and around Fort George Island, Kingsley acquired more than 1,000 acres of his own, cultivated at times by hundreds of enslaved Africans. His father’s Revolutionary-era losses haunted him, likely encouraging his participation in what he once called “the hideous traffic” in slaves. In 1802, he had written: “Insurance & other debts here have become like wild geese[:] the more you run after them the farther they are off.” For a time, he imported Africans, whether to work on his land or to sell them.

Sporadic violence flared throughout this Spanish frontier, intensifying during the so-called Patriots War of 1812-1814, which erupted when Americans from Georgia and South Carolina fomented a violent insurrection in Spanish Florida. That conflict was intermittently and secretly supported by President James Madison. Under coercion, Kingsley threw in with the Americans. Urged on by East Florida’s Spanish governor, Seminole warriors attacked and ravaged Kingsley’s plantations, nearly taking his life: “….I begin to hold scalping in less dread & think I may escape myself by very good luck….” he wrote.

In this lawless hinterland, blacks, enslaved and free, enjoyed some rights granted by their Spanish overlords. Not only could slaves and free blacks marry, but free blacks could own property, and slaves could buy their freedom. In his travels Kingsley had seen the advantages afforded by this leniency. On Hispaniola and Barbados, as well as in Guyana and Brazil, free Blacks had aided white plantation owners in suppressing slave rebellions, and Spanish Florida’s defense included free black militias. During the American Revolution, free blacks had fought on the side of the rebels, even though the British promised liberty to any slave who fought for the king. Kingsley’s plantation mirrored this three-caste system. He freed Anta and her children in 1811; he also freed his other three sexual partners and their mixed-race children. He encouraged his slaves to buy their freedom, provided they met his conditions.

By 1821, acknowledging its tenuous hold on them, Spain ceded its possessions in Florida to the United States. More white settlers poured into the territory, many bringing multiple slaves. A surge in cotton prices powered by a growing British market sent the price of slaves—crucial for working cotton—rising. Over the next decade, the territorial council drew an ever more restrictive color line. Free Blacks were barred from entering Florida; those already present could not assemble, carry guns, vote, or serve on juries; sex of any kind between whites and Blacks was banned. Ordinances made it prohibitively expensive to free enslaved people, and, once freed, they had to leave Florida within 30 days.

Kingsley disputed this approach, arguing that “color ought not to be a badge of degradation.” Instead, he said, the critical divide was between enslaved and free. He approved of slavery, and repeatedly argued in pamphlets he published that for maximum stability the system needed three castes: free Blacks, slaves, and whites. “In short consider that our personal safety, as well as the permanent condition of our slave property is immediately connected with, and depends upon our good policy in making it the interest of our free colored population to be attached to good order and have a friendly feeling towards the white population,” he wrote.

No record exists of Anta’s relationship with Kingsley. But Kingsley rightly feared that under Florida law, Anta and his other mixed-race partners and children stood in peril of being re-enslaved. In 1837 he purchased a redoubt in Haiti; his 32,000 acres were on what is now the northeast corner of the Dominican Republic. He sent his sons, 50 of his slaves—freed and recategorized as indentured servants—and other willing settlers, to establish a plantation there. Anta and other mixed-race family members, to whom in a will written in 1843 Kingsley left assets and 83 slaves, later joined the first arrivals. The settlement in Haiti eventually failed.

Kingsley nearly had it right about the subjugation of his kin. After his death in 1843, his sister Martha Kingsley McNeill and other white relatives contested his will. The plaintiffs alleged that the heirs, being of mixed race, had no right to inherit property. Sailing from Haiti to New York to protect the inheritors’ claim, Kingsley’s executor, Anta’s son George, drowned. Anta continued the fight and in 1848, a Florida judge with longstanding ties to Zephaniah Kingsley ruled in her favor. By then, however, legal fees had consumed much of the estate.

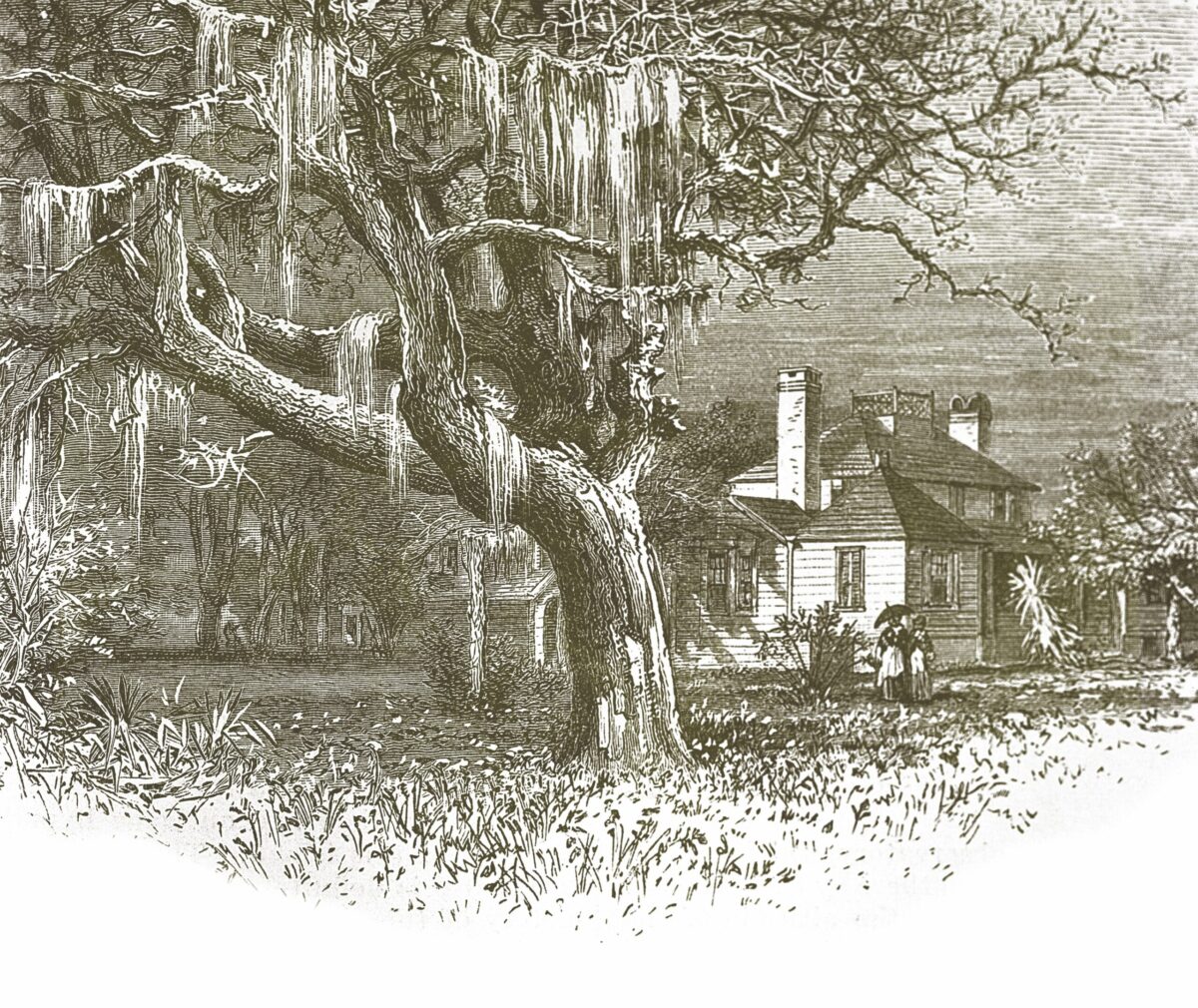

When the Civil War began, Anta, despite owning slaves, sided with the Union, and Federal troops occupied her Florida plantation. But the war ruined the land, and she went to live with a daughter nearby. In 1870, Anta was buried in an unmarked grave. The Kingsley estate in Duval County, with Zephaniah’s home and ruins of 25 slave cabins still standing, is part of the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, operated by the National Park Service.

The Kingsley saga continued to intertwine with American life. Martha Kingsley McNeill, who sued for her brother’s estate, was the grandmother of the painter James McNeill Whistler. Mary Kingsley Sammis, great-granddaughter of Anta, married Abraham Lincoln Lewis, who founded insurance company Afro-American Life. Lewis’s enterprise, which made him one of the first Black millionaires, also underwrote mortgages for Blacks. The company created American Beach, a resort on Amelia Island, Florida, that welcomed African Americans then barred from public strands.

This Cameo column appeared in the June 2020 issue of American History.