On April 5, 1869, Timothy Griffin woke from a disturbing dream. In it a presence conveyed to him that if he entered the Yellow Jacket mine once more, a terrible fate would befall him. Griffin treated the vision seriously, for he well knew that though the Yellow Jacket yielded ample silver, it exacted a toll in blood. After all, the previous July his cousin James from Cork, Ireland, and two fellow miners had been ascending the south shaft when the cage caught on a stray timber, snapping the hoist rope. Plummeting 260 feet, the cage struck the bottom of the shaft, instantly killing all three.

Unsettled, Griffin checked out of Gold Hill’s Vesey House the next morning, quit work and that night began the 240-mile journey west from Nevada to San Francisco. He left just in time. Early the next morning the Yellow Jacket was ground zero for the deadliest mine disaster in the history of the Silver State.

At 4 a.m. on the morning of April 7 the night crews of the Yellow Jacket, Kentuck and Crown Point mines—collectively known as the Gold Hill shafts—rose to the surface.

Although competitors, the men were well acquainted, for all three mines intersected. Partly this was to increase ventilation, for in the depths of the Comstock Lode, whose shafts descended more than 1,000 feet, temperatures could exceed 110 Fahrenheit. At other points the mines connected where crews—sometimes accidentally, often deliberately—had dug through into a rival shaft. With more wealth in silver concentrated in the mile-and-a-half stretch between Gold Hill and Virginia City than in all the gold discovered in California, playing dirty became second nature.

Of the managers of the three mines, those of the Yellow Jacket were the most aggressive. Its principal owner was William Sharon, one of the most notorious robber barons of the Gilded Age. In April 1864 the men of the Yellow Jacket waged a subterranean war with those of the neighboring Gentry. It began when Yellow Jacket miners cut a drift into the Gentry, set a garbage fire and smoked out the Gentry crews. The Gentry men responded by sealing off their shaft above the opening, which sent the smoke and foul vapors through the drift into the Yellow Jacket, driving their foes from the mine. The smudge war kept up for days, nearly asphyxiating one incautious Gentry miner, while the wind carried the stench to neighboring houses.

Five years later the Yellow Jacket would learn the consequences of playing with fire.

“Sure and Speedy Death”

Although no one knew exactly how the fire started, the prevailing theory was that a Yellow Jacket miner on the night crew negligently left a candle burning 800 feet below the surface, igniting the pine timbers between the Yellow Jacket and Kentuck. A few cried arson, a theory that would garner political consequences years later. Whatever the case, the fire smoldered for hours, generating billows of black smoke and a reserve of suffocating carbon monoxide that lingered in the depths of the mine.

At 7 a.m. 25 miners—most working the Crown Point, a handful the Kentuck—stepped onto the Crown Point cage. Descending rapidly, the men clung to the crossbar, knowing that any appendage carelessly extended between the cage and the timbered shaft risked amputation. A pair of miners were deposited at the 230-foot level, and several more at the 600-foot, 800-foot and 900-foot levels. Several Kentuck men unloaded as well—including B.F. Rogers and Martin Clooney. It took about 30 seconds to hoist up the empty cage, whereupon another group of Crown Point and Kentuck men stepped forward. Simultaneously, 100 feet to the north several dozen men from the Yellow Jacket descended in their own cage.

Yellow Jacket miners on the upper levels blithely began lighting candles. Meanwhile, the fire—fed by the sudden influx of oxygen—roared to life. Unable to support the weight of the earth, the weakened framework at the 900-foot level near the Kentuck boundary collapsed. The cave-in further fanned the flames and spawned a hellish gale of smoke and carbon monoxide that rushed outward with stupendous force.

John Murphy, who’d mined the Comstock Lode since its discovery in 1859 and served as stationman at the 800-foot level of the Yellow Jacket, had never felt anything like it. When the blast caught him, it snuffed out all 15 of his candles, leaving him choking in darkness. As chants of “Fire!” chorused throughout the mine, Murphy wrapped his rubber coat about his face. Even then, he was nearly insensible when pulled into a cage with Crown Point foreman George F. Kellogg and the Yellow Jacket’s underground foreman, Isaac S. Hubbell.

From 100 feet below him Murphy heard Jack Hogan weakly call out: “Murphy, where is all the smoke…? Send me a cage, I am suffocating to death.”

Instead, the desperate men aboard the cage signaled to be hoisted up. “These are the last words I heard from him,” Murphy later testified.

The blast hit the Kentuck equally hard. Rogers and Clooney were at the 800-foot level in that mine when the noxious gale engulfed them, dousing their candles. Blindly, the miners groped toward the Crown Point shaft. Rogers—who had cut his teeth as a Forty-Niner 20 years earlier—somehow made the shaft and ascended. Clooney fell behind, asphyxiated and died.

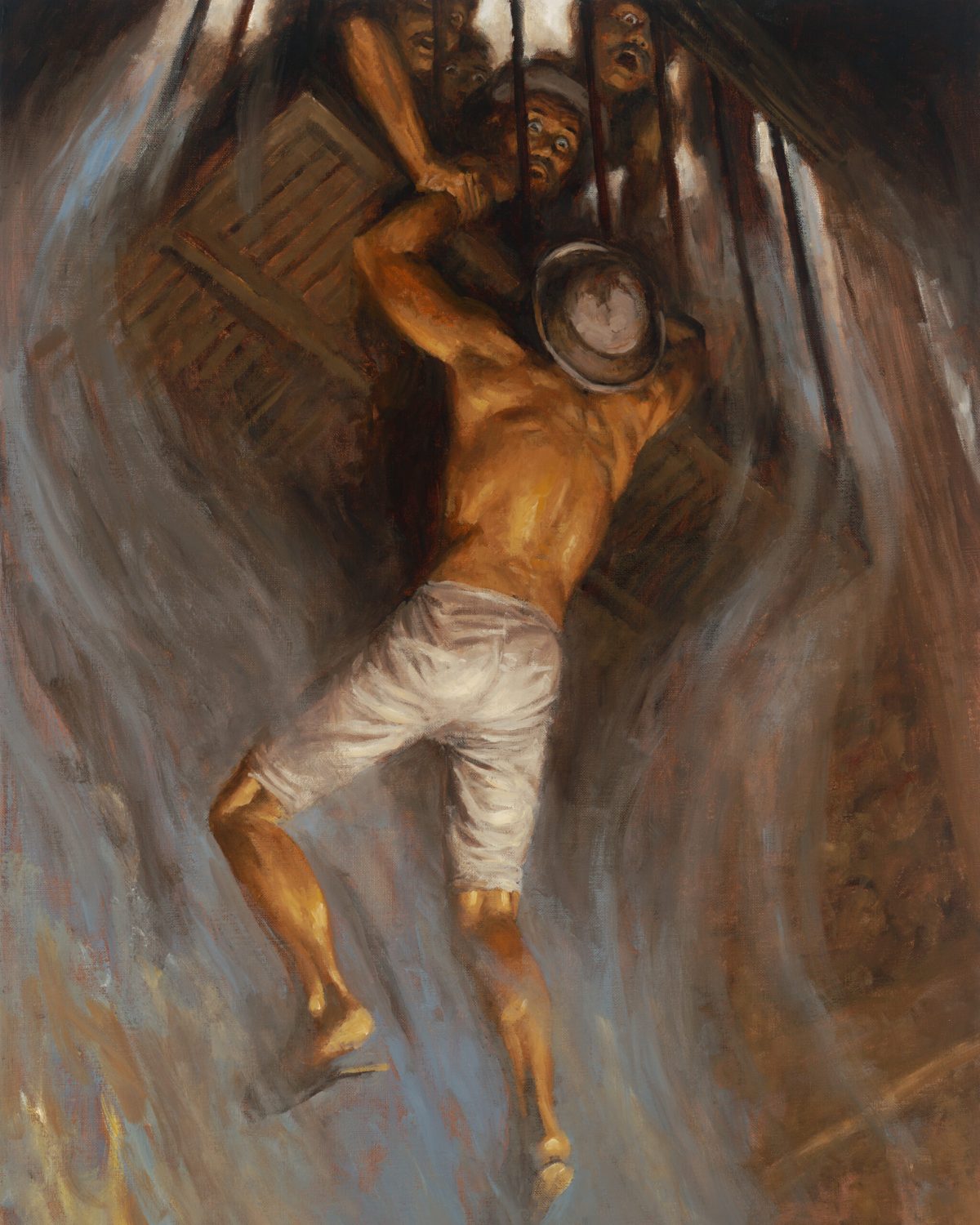

As dreadful as the events in the Yellow Jacket and Kentuck were, they played second fiddle to the nightmare unfolding in the Crown Point. The second cage had just passed the 700-foot level in its descent—having let off miners at various stations along the way—when the torrent hit. At the 800-foot level they came upon fellow miners gasping and choking in the smothering smoke. The Bickle brothers—James, George and Richard, strong young men from Yorkshire, England—were among them. The Englishmen and the others rushed to the cage but to their horror realized they would not fit. As the bell was pulled and the cage rapidly hoisted up, the men waited in darkness.

Thirty seconds later the cage reached the surface in a cloud of smoke. Once the men were clear, the engineers sent the cage back to the 800-foot level. Leaving brother James behind, George and Richard Bickle and just four others managed to stumble into the cage before someone pulled the bell. By the time they surfaced, only George drew breath. Although unconscious, he had an iron grip on the body of older brother Richard, who had slumped down while riding the cage. Having leaned too close to the edge, Richard had his head taken off at the jawline, and his left arm hung by a shred.

By then the air was alive with steam whistles, summoning firemen from Gold Hill, who blasted a stream of water down the Yellow Jacket shaft. As panic ensued, all of Storey County seemed to turn out. Father Pat Manogue came from St. Mary’s of the Mountains. Newspaperman Alfred Doten of the Gold Hill Daily News skipped breakfast and made for the mines. The families of the miners rushed to their loved ones, including the former Ann Hall, recently married to Kentuck miner Anthony Toy. Soon fire engines No. 3, 4 and 6 arrived from Virginia City. At about 9:30 a.m. the Kentuck cleared of smoke. Tom Smith, who had charge of the ropes, and another man descended into its shaft. A half hour later they emerged with the bodies of two men found at the 700-foot station: 30-year-old Patrick E. Quinn and 25-year-old Toy. After only 20 days of marriage Ann Toy was a widow. She wasn’t alone in her grief. Doten described “so many women hurrying wildly…at the scene of the disaster, loudly weeping or eagerly inquiring after the safety of those near and dear to them.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

As the smoke from the Yellow Jacket abated, Kellogg led down a rescue party of miners and firemen. They returned with four corpses from the 900-foot level. As for the Crown Point, the smoke blew so powerfully that no one dared enter.

Around noon John P. Jones—the industrious former sheriff of California’s Trinity County and current superintendent of the Crown Point and Kentuck mines—had an empty cage sent down the shaft to which was affixed a lighted lantern, a box of candles and a sheet of pasteboard scrawled with the following:

“We are fast subduing the fire. It is death to attempt to come up from where you are. We shall get you out soon. The gas in the shaft is terrible and produces sure and speedy death. Write a word to us and send it up on the cage, and let us know where you are.”

The hoistman lowered the cage to the 1,000-foot level, where a number of miners were known to have been working. Tense minutes passed. When the cage returned to the surface, all could see the lantern had blown out and the candles were untouched, signaling the worst. At that point roll was taken. One man was missing from the Yellow Jacket, four from the Kentuck and 23 from the Crown Point. Counting the six recovered bodies, that brought the death toll to 34.

“This is by far the most appalling, terrible and fatal calamity that has ever happened in the mines of the Comstock ledge,” Doten editorialized, “and not only falls like black clouds of terror over the whole community, but it carries deep sorrow and distress.”

The following day, at noon, George Bickle perished, bringing the probable total to 35. But George wasn’t the last to die. On Monday, April 19, William H. Williams was ascending from the 400-foot level of the Yellow Jacket when overcome by fumes. Swooning against the shaft wall, Williams was torn from the cage and fell 500 feet to the bottom. “Nearly every bone in his body was found to be broken,” Doten noted, “and his head torn completely off below the chin.”

Later that week, with the fires quashed and funerals over, the surviving Gold Hill miners returned to work. Three years would pass before rumors of arson sparked a political firestorm.

A Shocking Accusation

In the spring of 1872 James O’Donnell—who’d been foreman of the Yellow Jacket for eight years, although not at the time of the fire—met with mine owner William Sharon in San Francisco. To Sharon the onetime foreman confided having heard from a trusted source that the Yellow Jacket fire had indeed been arson.

According to O’Donnell, Ike Hubbell—underground foreman of the Yellow Jacket on April 7, 1869—had been approached by Crown Point foreman G.F. Kellogg the night before the fire. Hubbell alleged that Kellogg, in cahoots with Crown Point/Kentuck superintendent Jones, planned to set fire to the mine to crash the market, whereupon Kellogg and Jones would enrich themselves through the mining stock board. “Now, Hubbell, you stick to me, and I will stick to you,” Kellogg supposedly told Yellow Jacket’s underground foreman. “I know J.P. Jones will not throw off on me, for there is more money in J.P. Jones than in those sons of bitches Sharon and [Comstock investor] J.B. Winters.”

Hubbell, the story continued, wanted nothing to do with it. But several hours later, at 3 a.m. on the morning of April 7, Hubbell saw Kellogg at the 900-foot level with several carloads of blasting powder. A little before 7 a.m. Hubbell was on the 800-foot level when told the south end of the mine was on fire. Grabbing a pail of water, Hubbell dashed toward the fire, but the choking smoke forced him to crawl back to the shaft for fresh air. He and four or five other men then hopped aboard the cage. Before they could ring the bell, Kellogg joined them.

After being hoisted up, Hubbell whispered to Kellogg, “This is hell, and if it is found out, they will hang us all.”

Kellogg reiterated that if Hubbell stuck to him, he’d be all right. The superintendent then said aloud, “Everyone has come up—no one down there at all.” But that wasn’t the case. That evening Hubbell returned to the Yellow Jacket to help recover the bodies. The next day Kellogg cornered Hubbell, threatening to have him killed if he talked. Hubbell promised to keep silent. But Hubbell did tell his story to O’Donnell, who three years later shared it with Sharon.

“I had never believed that anyone had set the mine afire until hearing this man’s story,” Sharon reflected, “but then it at once flashed across my mind, from my knowledge of all the circumstances, that the story was true.”

Sharon instructed O’Donnell to bring Hubbell to San Francisco. O’Donnell did as bid, hopping a train to Carson, where Hubbell was employed as a guard at the Nevada State Prison. On April 29, 1872, Hubbell arrived on the noon train in San Francisco and checked into Room 330 at the Occidental Hotel. After dinner the next evening he returned to his room to find Sharon waiting in the sitting room. The mine owner introduced Hubbell to another man.

“This is my friend and private secretary,” Sharon said, “and whatever you say or agree to with him will be the same as if done with me.”

Sharon’s “secretary” had the look of a policeman about him and was, in fact, Captain Isaiah W. Lees, San Francisco’s chief detective. While Lees took notes, Sharon listened with interest to Hubbell’s yarn, particularly with regard to the culpability of Jones, who was in the running against fellow Republican Sharon for one of Nevada’s U.S. Senate seats. When Hubbell concluded his story, he expressed concern Kellogg or Jones would have him killed. On those grounds he refused to sign the affidavit.

Nonetheless, at 8 a.m. on May 6 Hubbell blurted to Jones’ friend Edmund Patten that he was about to sign an affidavit swearing Jones was behind the Yellow Jacket fire. Jones—who in 1870 had gained control of the Crown Point after striking a rich silver vein and subsequently purchased the Savage mine—was used to bunco artists and didn’t bite. Playing out the string, Hubbell met with Lees at the law office of Joseph P. Hoge, who had Hubbell’s statement transcribed into an affidavit. But when asked to sign the statement, Hubbell again refused, claiming fear of assassination.

“From his language I saw in a minute that he was talking money, and I would not lend myself to any such arrangement,” Captain Lees recalled. “He insinuated that he ought to be paid for his trouble, but I talked very severe to him, and that shut him up.”

Without a sworn statement the police could not move against Kellogg and Jones, but by then Lees doubted the entire yarn. Sharon still believed it, but whether anyone else would remained to be seen. Two days later all interested parties could judge for themselves. On May 8 the story broke in the San Francisco Chronicle. Hubbell’s accusation of arson proved so inflammatory that the paper sold out and was forced to print extra issues. Like wildfire the news spread to Gold Hill and Virginia City. If Sharon thought the “revelation” that Jones had masterminded the Yellow Jacket fire to make a fortune in stock market speculation would be met with outrage, he was correct. But he was dead wrong about at whom that outrage would be directed.

Rather than hanging Jones and Kellogg in effigy and demanding their arrest, residents on the Comstock Lode concluded Hubbell had created the story out of whole cloth. Furthermore, they accused Sharon of having paid Hubbell to blacken Jones’ reputation. Later that same day Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise issued the following broadside: “Aware that Mr. Jones is favored in his political aspirations by a majority of miners of Storey, Mr. Sharon, it is plain to everyone here, has resorted to this atrocious means.…Malevolence has never suggested a means of vengeance more monstrous, nor has hatred ever struck with fangs so envenomed.”

Things went worse for Hubbell. Pressed, he changed his story, claiming he’d only learned of Kellogg’s involvement indirectly and hadn’t personally seen the carloads of blasting powder. All the information he’d given Sharon had supposedly derived from witnesses.

Ultimately, Hubbell returned to Gold Hill to face the music. On August 9 a grand jury convened to rehash the particulars of the Yellow Jacket fire. Of the several witnesses called, none claimed they had seen any blasting powder, nor could any corroborate the allegations Hubbell had made in San Francisco. By then a new rumor was flying: Hubbell had told his tale to Sharon and leaked it to Jones in hopes of one of two outcomes—either Sharon would pay him to sign the statement, or Jones would pay him not to. Ultimately, the grand jury concluded that no evidence existed to suggest arson in the Yellow Jacket fire, further dragging Hubbell’s name through the mud.

On August 10 Doten noted in the Gold Hill Daily News that Hubbell had also been expelled from the Gold Hill Miners’ Union earlier that month “by a unanimous vote.” To Doten’s mind, at least, Hubbell had suffered enough. “He has been worried and harassed throughout this matter enough to drive a more sane man than he is crazy. He has no desire to make anymore ‘statements’ or create any more sensational reports.…Let Ike Hubbell alone.”

One man who couldn’t forget Hubbell was William Sharon. On March 4, 1873, Jones—whose image had only been helped by Hubbell’s scheming—assumed office as Nevada’s next U.S. Senator. His rival remained undeterred. Two years later, having successfully fought off allegations he’d put Hubbell up to it, Sharon was elected to Nevada’s other Senate seat, joining Jones in the U.S. Capitol. As for Ike Hubbell, having seen his career as a miner and a grifter flame out, he learned his lesson and stayed out of the headlines.

A frequent contributor to Wild West, Matthew Bernstein is the author of George Hearst: Silver King of the Gilded Age. For further reading he recommends Eliot Lord’s Comstock Mining and Miners and The Journals of Alfred Doten, 1849–1903. Special thanks to librarian Donnelyn Curtis for making those journals accessible.