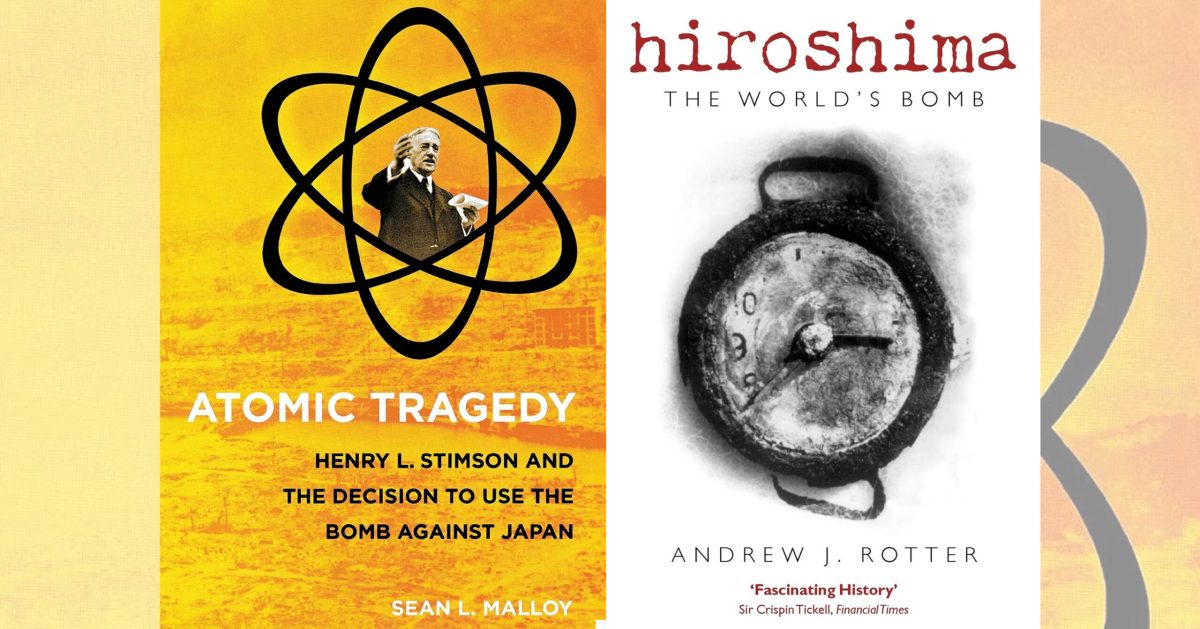

Atomic Tragedy: Henry L. Stimson and the Decision to Use the Bomb Against Japan By Sean L. Malloy, 233 pp., Cornell University Press, 2008, $26.95.

Hiroshima: The World’s Bomb By Andrew J. Rotter, 368 pp., Oxford University Press, 2008, $29.95.

Taken together, these two very different new works on the end of the Pacific war illuminate much of the current disputed terrain of this unending controversy. While Atomic Tragedy focuses a narrow lens on the role of Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson in the first use of atomic weapons, Hiroshima: The World’s Bomb strives for a wide-angle look at events from well before until long after the bombing.

Malloy’s stated purpose in Atomic Tragedy: to provide a context for the bombs’ use that incorporates a host of technical, diplomatic, military, political, and moral questions. He excels at untangling the chain of decisions that foreclosed or limited options long before Harry Truman entered the process. One key insight he advances shows how developers abandoned early concepts for weapons for underwater use against harbors (which might have significantly limited civilian casualties, in keeping with Stimson’s and army chief of staff Gen. George C. Marshall’s stated wishes), and instead shifted to designs for open-air use against cities. Malloy also properly emphasizes that Stimson had a key formal position, as well as great informal power by virtue of his high-level experience with foreign and military affairs, as well as his keen moral sensibilities.

Malloy’s volume earns many positive marks. In a refreshingly measured tone, he fully acknowledges the multiple challenges and uncertainties faced by Stimson and other American leaders. He also underscores a point now acknowledged by some revisionists: that Japan’s leaders bear the primary responsibility for the ultimate use of the bombs. In fact, both Malloy and Rotter jettison the incendiary revisionist argument that Japan’s leaders, recognizing they were hopelessly defeated, were on the cusp of surrender in August 1945.

Echoing historians like Gar Alperovitz and Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Malloy also posits that a promise to preserve the emperor, along with the Soviet signature on the July 1945 Potsdam Declaration (carrying the implicit threat of imminent entry into the war against Japan), might have secured Japan’s surrender without recourse to atomic weapons.

This thesis retools the premier revisionist argument, but houses a number of fallacies. The first major defect in this framework is the assumption that ending the war turned solely on a decision in Tokyo, when it actually required two steps: a political decision in Tokyo to surrender, and the compliance of Japan’s armed forces, scattered across the Pacific and Asia. Fears about compliance weren’t limited to the abortive coup d’état of August 14–15, when a small band of field-grade officers sought to nullify the emperor’s decision to surrender. Much more serious was the threat of mutiny by two of three major overseas commanders, who together directed between a quarter and a third of Japanese forces. As late as August 19, Japanese commanders feared that the Imperial Army defenders were on the verge of defeating the first Soviet landing on the Kuril Islands, an event that would have unraveled the whole surrender process. It took repeated orders, including from the emperor himself to foreclose this peril. Omitting this vital aspect of the situation makes the actual outcome—the organized surrender of both Japan and its armed forces—seem like the inevitable finale rather than what it was: a near-miraculous deliverance that rerouted history before it plunged into an even deeper abyss.

And there is a second major infirmity in this revisionist scenario. As historian Robert Butow pointed out over a half-century ago in his pathbreaking Japan’s Decision to Surrender, only eight men controlled Japan’s fate: Hirohito, his principal adviser Koichi Kido, and an inner cabinet called the Big Six.

Not one of these individuals indicated on the record, prior to or after the war, that the revisionists’ proposed diplomatic initiatives would have prompted them to surrender. In fact, both the emperor and Kido had particular opportunity and powerful motive to make such claims; they did not.

Because he attempted to modify the Potsdam Declaration, Stimson figures critically in Malloy’s argument. But Stimson’s proposed draft additions stipulated only that the Japanese could maintain a “constitutional monarch under the present dynasty.”

They did not guarantee to leave Hirohito as emperor. This is enormously important, for Hirohito’s maneuvers demonstrated that preserving his own inviolability, not just the imperial institution, figured centrally in his actions. Unfortunately, Malloy’s discussion of this becomes so confused that the reader cannot grasp that crucial distinction.

This leads to an error uncharacteristic of Malloy’s otherwise earnest efforts. He states that on August 10, 1945, the Japanese government offered “to accept the terms outlined in the Potsdam Declaration with the sole reservation that the institution of emperor should be allowed to continue after the war.” He cites Hasegawa’s Racing the Enemy as authority for this proposition, which is crucial to his argument. But Hasegawa, accurately reflecting recent scholarship, emphasizes that the Japanese proposal demanded the Allies guarantee the emperor’s supremacy over not just the Japanese government but also the commander of the occupation, thus giving the emperor veto power over occupation reforms.

Another serious error appears in Malloy’s approach to radio intelligence. Acknowledging that my book Downfall asserts the significance of diplomatic and military intercepts of Japanese messages, he holds up Alperovitz’s Atomic Diplomacy to buttress his interpretation that they were “ambiguous” and not worth extended discussion. The problem is, Atomic Diplomacy appeared in 1965, before the classified diplomatic and radio intelligence material was released. So Alperovitz could hardly bear accurate witness about the material’s import.

Rotter’s Hiroshima, if not wholly original in concept, is both exceptionally intelligent and elegant in execution. His powerful major theme: that a vast international cast contributed to both the development of nuclear weapons and the context of their only combat use in 1945.

The book opens with a deft description of the global “republic of science” peopled by physicists, which respected achievement but not national boundaries. Foremost in this “republic” was Niels Bohr, a Dane who believed physicists should be the final arbiters of man’s relation to the atom. Rotter shrewdly points out that the moral context for the use of atomic weapons really begins in World War I, when the republic of science fractured along national lines, and poison gas, an indiscriminate weapon like the atomic bomb, was created and universally used with devastating, lingering results.

A few examples must serve to illustrate Rotter’s thoughtful probe into a maze of critical issues. In a remarkably concise section, he dissects the German and Japanese efforts to build an atomic bomb and dismisses the myth that the top German physicist, Werner Heisenberg, and his colleagues sabotaged their efforts for humanistic reasons. Rotter finds ample evidence that American leaders thought about the atomic bomb’s possible effects on their fraying alliance with the Soviets, including its use as leverage.

But he finds more compelling the insight originated by Barton Bernstein: that any effect on American-Soviet relations was not a cause but a “bonus” accruing from the development program’s driving rationale that the bombs would be used against the Axis. Finally, Rotter sees little prospect that a promise to preserve the emperor would have secured Japan’s surrender, and correctly notes the ominous implications of the radio intelligence available to American leaders.

Rotter is subtle about the moral issues. He emphasizes that there had been a worldwide “moral eclipse” among leaders by 1945, after years of mounting bloody horrors, but points out that American policymakers could not really “imagine the destruction and horror” the bombs would wreak. (Some of them, like Truman, engaged in self-deception about the likely mass death of civilians.) Unlike Malloy, Rotter provides a nuanced account of Japan’s surrender, concluding that both the bombs and Soviet entry were important. He also highlights two other important factors: Hirohito’s fears of domestic revolution and of the military’s noncompliance with his order to surrender.

Readers will differ on whether Hiroshima is burnished or marred by venturing beyond 1945 to describe various atomic bomb programs. But where Malloy provides some new insights and thoughtful revisionism, Rotter casts a brighter, more extensive light.

Originally published in the November 2008 issue of World War II Magazine. To subscribe, click here.