Rear Adm. Isaac Campbell Kidd

KIA Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941

Isaac Campbell Kidd was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on March 26, 1884, graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1906 and taking part in the Great White Fleet’s globe-girdling “show of the flag” in 1907-1909. During World War I he served aboard the battleship USS New Mexico.

Kidd had attained the rank of rear admiral, commander of Battleship Division 1 and chief of staff and aide to the commander of the Battleship Battle Force at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by Dec. 7, 1941. He was ashore when a force of six Japanese aircraft carriers attacked Pearl Harbor that morning.

Hastening aboard his flagship, the battleship USS Arizona, he directed its defense until bombs penetrated its bridge and magazine, destroying the ship and killing 1,177 of its crew. Although Kidd’s body was never found, his Academy ring was found fused to the bridge’s bulkhead, as was a trunk containing his personal effects, which were returned to his widow. The first U.S. flag officer killed by a foreign enemy, Kidd was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Adm. Sir Tom Phillips

KIA Kuantan, Dec. 10, 1941

Born in Pendennis Castle, Falmouth, Cornwall on February 19, 1888, Sir Thomas Spencer Vaughn Phillips was nicknamed “Tom Thumb” due to his stature. He came from a long line of military figures and chose the Royal Navy in 1903. During World War I he led destroyers in the Mediterranean Sea and Asia.

From 1920 to 1922 he was a military adviser on the Permanent Advisory Commission for Naval, Military and Air Questions Board at the League of Nations. On Jan. 10, 1939 he was made rear admiral and naval adviser to King George VI. In May 1941 he was given command of the Far Eastern Fleet with the rank of acting admiral. It was not until Dec. 2, however, that he boarded the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, which became the flagship of Force Z, along with battlecruiser HMS Repulse and four destroyers.

On Dec. 8 (simultaneously with the attack on Pearl Harbor, across the International Dateline), Japanese forces landed at Kota Bharu, British Malaya. On Dec. 9 Adm. Phillips led Force Z out of Singapore to disrupt another Japanese landing at Kuantan, but was spotted and reported by Japanese submarine I-65. Japanese naval support, including battleships Kongo and Haruna, was dispatched to intercept, but failed to make contact. The next day, 86 Mitsubishi G3M2 and G4M1 bombers of the Saigon-based Genzan, Kanoya and Mihoro kokutais (air groups) attacked the force, which had no air cover of its own.

The result was the first victory of air over naval power on the open sea, with both capital ships torpedoed and sunk. Repulse took 426 crewmen down with it, while Prince of Wales’ 327 fatalities included its captain, John C. Leach, and Phillips, who chose to go down with their ship.

Karel Doorman

KIA Java Sea, Feb. 28, 1942

Karel Willem Frederik Marie Doorman was born in Utrecht on April 23, 1889 and in 1906 he and his brother enlisted in the Royal Netherlands Navy as midshipmen. In 1910 Karel received his officer’s commission and was first assigned to the Dutch East Indies. In March 1914 he requested transfer to aviation and from 1915 to 1921 he served as a flight instructor. As commander of Naval Air Station De Kooy at Den Helder, his outstanding organization and running of the base led to his being awarded the Knight of the Order of Orange-Nassau. In 1934 he went back to the Indies and in 1938 was placed in command of aviation there.

After the Netherlands was overrun by the Germans in May 1940, the Netherlands maintained a government- in-exile in Britain and held on to their Far Eastern colonies. On May 16 Doorman was made a rear admiral and on June 13 was given command of the naval squadron there, flying his pennant from the light cruiser De Ruyter.

When Japan entered World War II and sent invasion forces to the Netherlands East Indies, Doorman was put in command of ABDA Command, a polyglot collection of available American, British, Dutch and Australian warships. Japanese aircraft foiled an attempt to stop them at Makassar on Feb. 4. Another attack against Japanese landings on Bali ended in failure in the Bandung Strait on Feb. 19, with destroyer Piet Hein sunk by Japanese destroyer Asashio.

When an invasion force moved on Java, Doorman led ABDA force to oppose it on Feb. 27, only to be engaged by the Japanese escort force, including heavy cruisers Nachi and Haguro and light cruisers Jintsu and Naka. The two sides were fairly evenly matched, but Doorman had the handicap of trying to coordinate efforts of commanders of four different nationalities.

He held his own for seven hours, but on the 28th Nachi managed to torpedo De Ruyter, Haguro torpedoed light cruiser Java and the Allied formation disintegrated—and with it, Allied hopes of saving Java. Doorman chose to go down with his flagship. He was posthumously made a Knight 3rd Class of the Military William Order.

Rear Adm. Tamon Yamaguchi

KIA Midway, June 5, 1942

Born Aug. 17, 1892 in Koishikawa Tokyo, Tamon Yamaguchi came from a samurai family and was given the childhood name of a legendary 14th century samurai, Kusunoki Masashige. In 1912 he graduated 21st out of 144 cadets from the Naval Academy. July 1918 saw him aboard Kashi, part of a squadron based at Malta. From 1921 to 1923 he attended Princeton University, N.J. and in 1927 he served on the General Staff. During the war in China, he commanded the light cruiser Isuzu, battleship Ise and the 1st Combined Air Group, rising to rear admiral on Nov. 15, 1938.

By Dec. 7, 1941, Yamaguchi was in command of the 2nd Koku Sentai (air division) of Vice Adm. Chuichi Nagumo’s 1st Kido Butai (air fleet), consisting of aircraft carriers Soryu and Hiryu, which attacked Pearl Harbor and supported the invasions of Wake and Ambon islands, a bombing strike on Darwin, Australia and carrier raids on Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

By the Battle of Midway on June 4, 1942, Yamaguchi had shifted his pennant from Soryu to Hiryu. When reconnaissance planes spotted the carrier USS Yorktown in the vicinity, he urged Adm. Nagumo to launch all his Nakajima B5N2s against the American ships with the bombs they held, rather than wait to replace them with torpedoes.

Nagumo overruled him, resulting in the Americans arriving just in time for Douglas SBD-2 dive bombers from carriers Enterprise and Yorktown to inflict fatal damage to carriers Akagi, Kaga and Soryu. They failed to find and destroy Hiryu. Its B5N torpedo planes and Aichi D3A1 dive bombers struck back, crippling carrier Yorktown before Hiryu was disabled by Enterprise’s SBDs. On June 5, Yamaguchi ordered his crew to abandon ship. He and Captain Tomeo Kaku chose to go down with the doomed vessel.

Rear Adm. Aritomo Goto

KIA Cape Esperance, Oct. 12, 1942

Born in Ibaraki Prefecture on Jan. 23, 1888, Aritomo Goto graduated from the Naval Academy in 1910 and served aboard a wide variety of ships. In World War I he manned a radio outpost in the South Pacific. On Nov. 15, 1939 he was made rear admiral and given command of the 2nd Cruiser Division.

On Sept. 10, 1941, Goto was put in command of the 6th Cruiser Division, consisting of heavy cruisers Aoba, Furutaka, Kinugasa and Kako. His cruisers played supporting roles in the second assault on Wake on Dec. 23, 1941, and in the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942. August 1942 saw the 6th Cruiser Division based at Kavieng and Rabaul, New Britain, when U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal.

Goto joined Vice Adm. Gunichi Mikawa for the nocturnal Battle of Savo, and the sinking of heavy cruisers USS Astoria, Quincy and Vincennes, and RANS Canberra. While returning to Kavieng, however, Kako was waylaid and sunk by the U.S. submarine S.44.

The tables were turned on the night of Oct. 11. Goto, leading a mission to bombard Henderson Field while Japanese army reinforcements were being shipped to Guadalcanal, ran into an ambush of U.S. Navy cruisers and destroyers under Rear Adm. Norman Scott off Cape Esperance. The Americans lost the destroyer USS Duncan, but sank Furutaka and badly damaged Aoba, whose casualties included Goto, who died of his wounds the next day.

Rear Adms. Daniel J. Callaghan and Norman Scott

KIA Guadalcanal, Nov. 12-13, 1942

Daniel Judson Callaghan was born in San Francisco, California on July 26, 1890 and graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1911. After commanding the cruiser New Orleans during World War I, he served as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s naval aide from July 1938 to May 1941, when he was given command of the heavy cruiser San Francisco. In April 1942 he was made a rear admiral and chief of staff to Vice Adm. Robert L. Ghormley.

Born in Indianapolis, Indiana on Aug. 10, 1889, Norman Scott graduated from the Naval Academy in 1911. He was executive officer on the destroyer USS Jacob Jones when it was torpedoed between Brest, France and Queenstown, Ireland by the German submarine U-53 on Dec. 6, 1917. With 66 sailors killed and two captured by U-53 (which then radioed its victim’s coordinates to Queenstown), Jacob Jones was the first American warship sunk in action during World War I. Scott later served as naval aide to President Woodrow Wilson and commanded Eagle boats in 1919.

Scott’s career continued through World War II, when he made rear admiral in May 1942. He commanded the light cruiser USS San Juan in August and in September was given command of cruiser and destroyer equipped Task Force 64, whose personnel he trained to realize his aggressive approach to combat, including night fighting. This paid off at Cape Esperance on the night of Oct. 11-12, when Scott “crossed the T” on Japanese Cruiser Division 6, killing Rear Adm. Aritomo Goto, damaging his flagship Aoba, and sinking heavy cruiser Furutaka.

Callaghan was in command of Task Group 67.4 when the Japanese sent two battleships and other warships under Vice Adm. Hiroake Abe to bombard Henderson Field at Guadalcanal on the night of Nov. 12-13, 1942. An aggressive officer who trained his men in gunnery, Callaghan was posthumously criticized for failing to issue a battle plan to his scratch force and not taking advantage of his newest radar. Scott was present aboard light cruiser Atlanta. At the time, many naval officers believed the battle would have turned out differently had Scott been in overall command.

Both forces advanced to point blank range before they became aware of each other, resulting in the wildest, most violent surface encounter of the war. Atlanta demolished the Japanese destroyer Akatsuki and damaged Ikazuchi but took a torpedo from either Ikazuchi or Inazuma. Nearby, San Francisco battled the battleship Kirishima, light cruiser Nagara and a destroyer, also landing 19 8-inch shells on Atlanta, striking its bridge and killing Scott. Badly damaged, Atlanta was scuttled three miles east of Lunga Point. San Francisco survived the carnage with 77 crewmen dead, including Callaghan. The Japanese, whose losses included the battleship Hiei, withdrew, leaving the Americans victorious. Both Callaghan and Scott were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Rear Adm. Henry Mullinnix

KIA off Makin, Nov. 24, 1943

Born in Spencer, Indiana on the Fourth of July 1892, Henry Maston Mullinnix graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy first in his class in 1916. Studying aeronautical aviation, Mullinnix qualified as an aviator on Jan. 11, 1923, going on to advance the use of air-cooled engines in naval aircraft.

On Nov. 13, 1942, Mullinnix was promoted to rear admiral and commanded the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga from April to August 22, 1943. After some shore duty with a carrier division, Mullinnix was sent to the Central Pacific in command of Task Group 52.3—Air Support Group of Northern Attack Force (Makin), Task Force 52—with the escort carrier USS Liscome Bay as his flagship.

On Nov. 20, U.S. Army soldiers of the 165th Infantry Regiment landed on Makin in the Gilbert Islands and the island was secured by the 24th. That day, however, Japanese submarine I-175 slipped into the task group and fired a spread of three torpedoes at the aircraft carrier.

At least one struck home, penetrating to the magazine and blowing the ship apart. Only 272 of its crew survived; the 644 killed included Adm. Mullinnix, Captain Irving D. Wiltsie and Cook 3rd Class Doris Miller, who earned the Navy Cross for his efforts to defend his ship during the Pearl Harbor raid. Mullinnix was posthumously awarded the Legion of Merit with Combat “V.”

Vice Adm. Shoji Nishimura

KIA Surigao Strait, Oct. 25, 1944

Born on Nov. 30, 1889, Shoji Nishimura graduated from the Naval Academy in 1911 and was widely characterized as a “sea dog” who abhorred onshore assignments. In November 1941 he got his first command, Destroyer Squadron 4. The death of his only son in an air accident on Dec. 23 left him with a fatalistic streak.

His performance in battle was mixed at best. Near Bali on Jan. 24, 1942, his squadron chased a Dutch submarine while four U.S. Navy destroyers savaged the convoy he was supposed to escort. At the Java Sea on Feb. 27, his squadron failed to score a single torpedo hit (including the eight launched from his flagship, light cruiser Naka). During the Second Battle of Guadalcanal on Nov. 14-15, 1942, Nishimura’s destroyers failed to land a single torpedo hit.

In spite of that poor record, Nishimura was promoted to vice admiral in September 1944 and put in command of Battleship Division 2. On the night of Oct. 24-25, 1944, he led his unit in attacking the American beachhead on Leyte from the south, only to run into most of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, including six battleships, at Surigao Strait. It was clearly a suicide mission.

Nishimura lost battleship Fuso and three destroyers to American destroyers’ torpedoes before he even reached the enemy battle line. He engaged the battleships until he went down with his flagship, Yamashiro, under an avalanche of shells and possibly four torpedoes. Of the seven warships he led up the strait, only the destroyer Shigure escaped intact.

Vice Adm. Seiichi Ito

KIA East China Sea, April 7, 1945

Born on July 26, 1890 in Miike County (now Miyama City, Fukuoka Prefecture), Seiichi Ito graduated from the Naval Academy in 1911 and rose rapidly though the Japanese naval staff. Like Isoroku Yamamoto, he was a staunch proponent of maintaining good relations with the United States. He rose to vice chief of staff of the Imperial Navy General Staff and on Oct. 1, 1941 was made a vice admiral. In December 1944 he commanded the 2nd Fleet in the Inland Sea.

After the Americans landed on Okinawa on April 1, 1945, Ito was ordered to lead an operation in which the colossal battleship Yamato would force its way to Okinawa, run itself aground and shell the American beachhead until it ran out of ammunition. Ito protested that this would be a waste of resources.

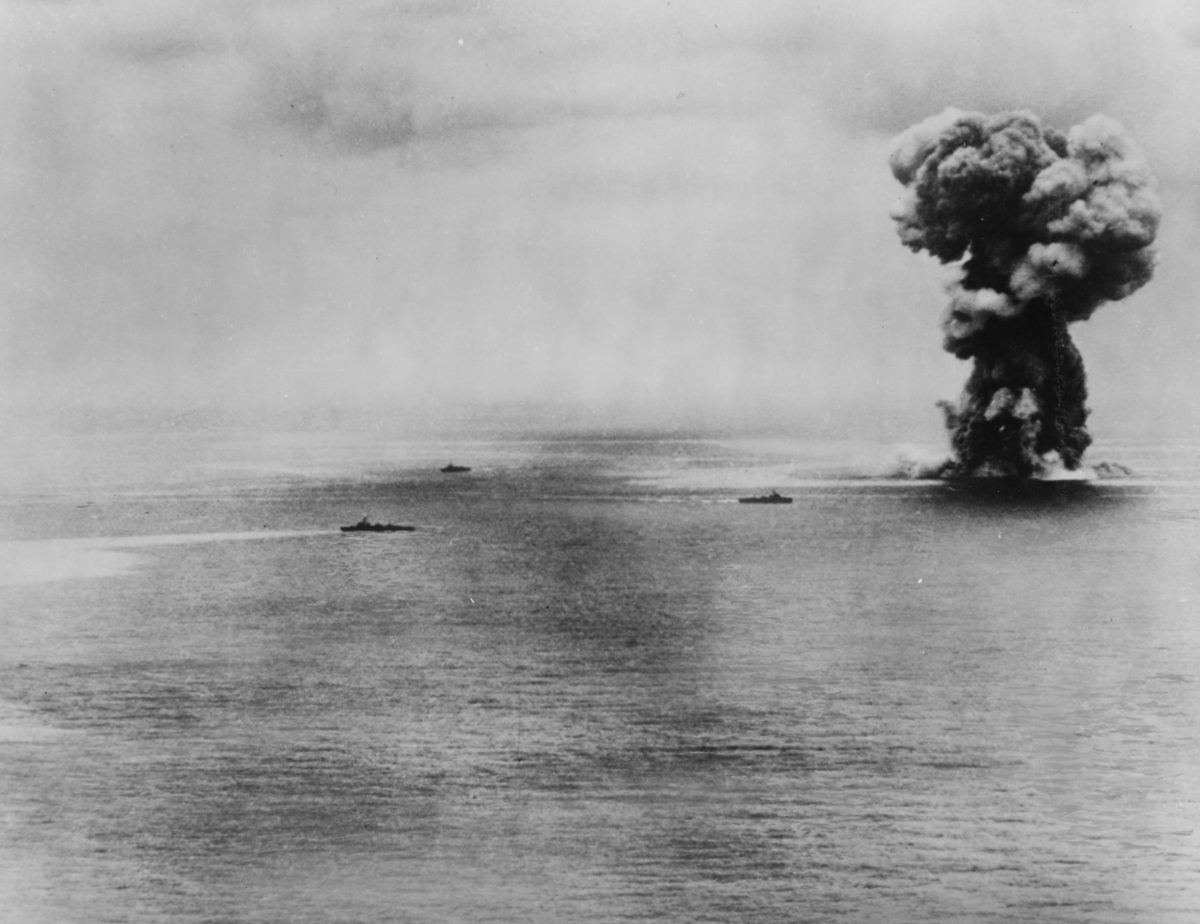

However, when told that the Emperor expected the High Seas Fleet to do something, he obeyed and personally led Yamato, escorted by the light cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers. The unit was spotted and came under attack on April 7, 1945 by hundreds of U.S. Navy carrier planes.

Hit by at least 11 torpedoes and six bombs, Yamato was sunk, along with Yahagi and four of the destroyers. Ito’s last order was to cancel the operation and have the remaining destroyers rescue whoever they could before he joined the 3,055 of 3,332 crewmen who went down with Yamato. Ito was posthumously promoted to full admiral. His only son was killed 10 days after his death flying a kamikaze plane to Okinawa.