On August 2, 1972, standing near a taxiway at Wittman Field in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, I pressed a check for $200 into the hand of a short, fat guy in a red shirt. His name was Jim Bede and he was promising to deliver, at some unspecified future date, the parts and materials for me to build a tiny single-seat airplane that looked like a rocketship and was powered by a snowmobile engine. The kit, he promised, would take only about 600 man-hours to assemble—just four months of full-time work—and cost no more than a new Volkswagen Beetle.

The tiny plane was called the BD-5 Micro. More than 3,000 people—many of them, like me, with imaginations fired but zero experience building airplanes—eventually purchased BD-5 kits. A handful of factory prototype BD-5s made test flights, triggering paroxysms of excitement among us kit-buyers. But plagued by the lack of a reliable engine and reckless financial mismanagement, Bede never delivered a single complete BD-5 kit. The company eventually went bankrupt, and thousands of Bede customers ended up losing some $10 million.

Yet the plane’s allure remained undimmed. A number of diehard builders managed to complete and fly jury-rigged BD-5s powered by improvised engines. In the process, they crashed and killed themselves in horrifying numbers.

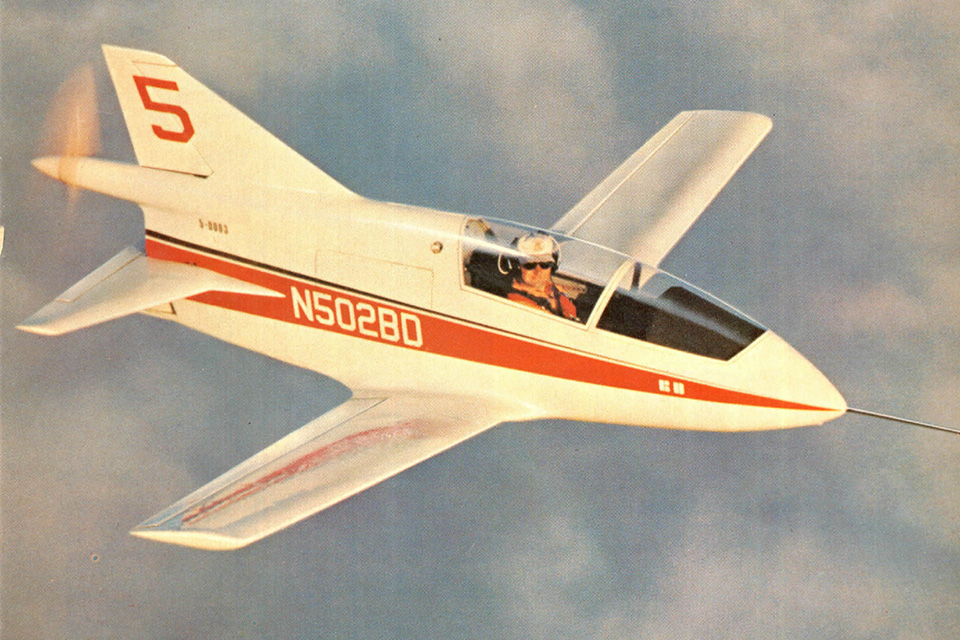

But when I recall watching an airshow trio of jet-powered BD-5Js swoosh by at 300 mph, or think back on my brief 1974 flight in a factory prototype, there’s no doubt in my mind: Almost 50 years later, the BD-5 is still the coolest lightplane ever, still the ultimate private pilot’s fantasy.

Jim Bede’s place in aviation history is that of both visionary and charlatan. An aeronautical engineer with an upbeat, fast-talking personality (“100 words a minute, with occasional gusts to 150,” as he put it), Bede was part of a grassroots clan of sport pilots frustrated and bored by expensive, stodgy Cessnas and Pipers.

In the early 1960s, Bede designed and promoted the BD-1, a conventional-looking two-seater intended to be fabricated by amateur homebuilders. In a harbinger of things to come, he ran out of money before he could finish the project. Outside investors took over, kicked Bede out and redesigned the BD-1 as an FAA-certified production aircraft, the American AA-1 Yankee.

His next project was the BD-4, a boxy, easy-to-build four-place homebuilt. He started selling BD-4 construction drawings in 1968, and in 1970 introduced prefabricated kits—a new idea at the time. And a splendid idea it turned out to be; several hundred BD-4s were completed, and many are still flying.

Encouraged by the BD-4’s success, in November 1970 Bede offered for sale a $5 information packet about his latest concept: a plane so small and sleek that the pilot had to lie semi-supine beneath its fighterlike canopy. The promised specs were astounding: a top speed up to 270 mph, full aerobatic capability and a basic kit price of just $1,800. He cashed the first $200 deposits for the still-imaginary plane in February 1971.

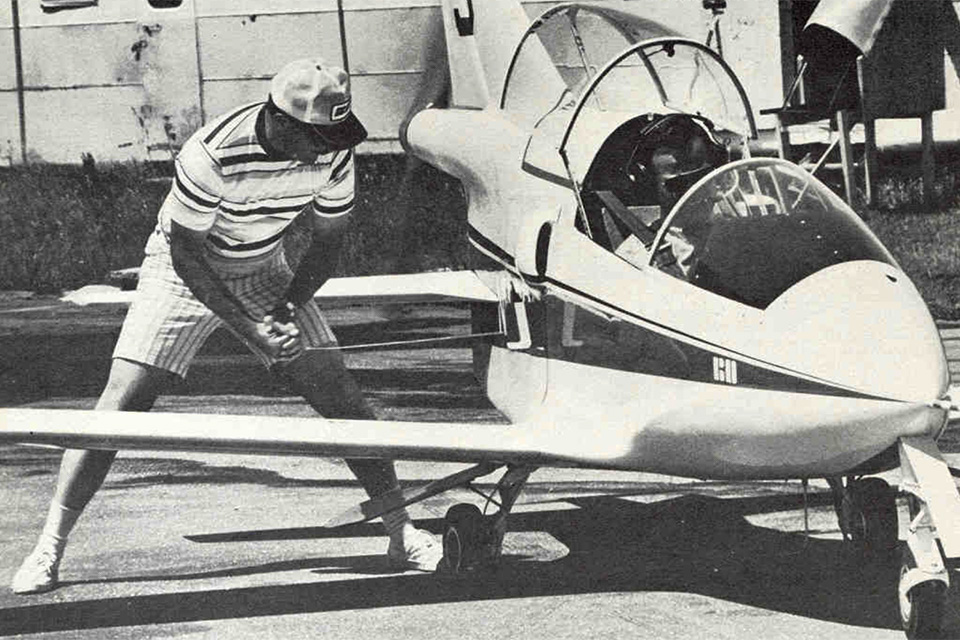

The tangible BD-5 made its public debut in July 1971 at the Experimental Aircraft Association’s annual Oshkosh fly-in. Not yet flyable, but looking very badass indeed, the tiny red plane was an instant sensation. By the end of the show, the bullhorn-wielding Bede, ever the carnival barker showman, had collected more than 800 deposits.

That first BD-5, N500BD, had a fiberglass fuselage, a V-tail and a 36-hp Polaris snowmobile engine. It flew, briefly and barely, on September 13, 1971—a short hop down the runway, with Bede at the controls. The little plane proved wildly unstable. A second brief hop was equally precarious, and it never flew again. But in another ominous harbinger of things to come, a subsequent Bede newsletter cheerily reported that the company was “quite pleased with the results….of these flight tests,” conveniently neglecting to mention that the plane never got more than a couple feet off the ground.

Soon thereafter Bede made what was perhaps the best decision of his aviation life: He hired a 28-year-old stability-and-control engineer from Edwards Air Force Base in California to be his director of development. The young fellow’s name was Burt Rutan.

Rutan arrived at Bede headquarters in Newton, Kansas, in March 1972. The second BD-5 prototype, N501BD, was then under construction. The new version was made of aluminum and had a conventional vertical tail, a swept horizontal stabilator and a 40-hp Kiekhaefer snowmobile engine. Rutan’s job: get the airplane ready to fly and conduct the flight-test program. One of his first moves was to hire a friend and fellow engineer from Edwards, Les Berven, as chief test pilot.

Rutan quickly discovered that 501 was hideously tail-heavy. (Solution: Fill up the nosecone with lead.) The flaps had to be redesigned. High-speed taxi-testing led to a complete redesign of the stabilator. After a deal to buy production engines from Kiekhaefer fell through, a German-made 40-hp Hirth snowmobile engine was substituted.

In May 1972, eight months after the first runway hop and 15 months after the first deposit checks had been cashed, the BD-5 finally made its first up-and-away flight. It was brief; the Hirth engine overheated within seconds and the cockpit filled with smoke. Berven shut down the engine and glided back to a safe landing. But at least the flight-test program was finally underway.

The smoke and overheating problems were quickly fixed. Berven reported that the plane flew beautifully, with good stability and “the best-harmonized controls I’ve ever flown.”

But, recalls Rutan, “We had many engine failures.” One came during a demo flight in front of FAA officials, from whom Bede was seeking a permit to fly at the 1972 Oshkosh confab. With the FAA men watching, the engine seized 90 seconds after takeoff. Berven managed to glide back to the runway, but ran off the end and crunched the nose gear. No permit.

The plane’s failure to fly at Oshkosh that year didn’t dissuade me, nor many others, from handing Bede deposit checks. (Hell, the thing looked like it was going 200 mph just sitting there on the ground!) A month later, 6,000 people showed up at Bede’s home field to watch the first public flight demonstration.

The following month, however, 501 crash-landed on a road after another engine failure. Rather than repair the substantial damage, Bede scrapped it and focused on the next prototype, N502BD, scheduled to fly in a couple of months. But vibration problems with a new belt-drive system persisted, and by the time Bede began to ship the first partial kits to long-yearning builders in early 1973, 502 had still not flown.

At this point, Rutan was having second thoughts about Bede’s business practices: “I was thinking, if we can’t even fly the airplane for two minutes, how can we be sending out kits?”

Perhaps money had something to do with it. The BD-5 program had been puttering along for more than two years on Bede’s personal funds and about $600,000 in kit deposits. But once the first partial kit packages were ready for shipment, builders had to come up with the full balance—in my case, $2,385. Multiplied by 3,000 customers, that worked out to about $7 million.

UPS dropped the first two big cardboard cartons in my driveway in March 1973. They contained the canopy, airspeed indicator (it read up to 300 mph!), wheels and brakes, and prop spinner, plus the parts to build the vertical stabilizer’s framework. But no plans or instructions. I spent a lot of time staring at the airspeed indicator and fondling the spinner.

In April the wing kit arrived, with a set of excellent plans and instructions, and I at last began what I hoped would be my 600-hour journey to flying nirvana.

Meanwhile, back at Bede, with partial kits now shipping, the money flowed in. And out. The 502 prototype finally flew in March 1973, but the belt-drive system and the Hirth engine continued to cause problems, triggering more forced landings. The Hirth also lacked the power to meet the plane’s promised performance. “It was becoming clear that this was a junk engine,” notes Rutan.

Despite Bede’s desperately upbeat reports to its customers (“The basic twin-cylinder engine manufactured by Hirth is as good, or better, than any engine we have had the opportunity to study and test….”), it was around this time that the rumblings of discontent among us builders began.

Perhaps as a distraction from all the engine problems, in mid-1973 Bede fired a double-barrel shot of adrenaline into the Micro community: the promise of an FAA-certified production model, the BD-5D, and a real-life jet-powered version. Slick two-page color ads in aviation magazines (“You’ve just run out of excuses for not owning your own airplane”) sent ripples beyond the world of homebuilding. The ready-to-fly production BD-5D, it was promised, would cost less than half the price of the cheapest new plane then available, yet fly twice as fast. Send in your deposit now! Just $400! “He needed a new product, and he needed it fast,” recalls Rutan.

Powered by a minuscule 200-pound-thrust French Microturbo TRS-18 turbojet engine, the BD-5J set the 1973 Oshkosh airshow crowd agog. (A landing accident caused by a stuck thrust attenuator dampened spirits not a whit.) It flew so well and so reliably that six months later Bede let the first aviation journalist, former U.S. Air Force F-86D Sabre pilot Dick Weeghman, take a test hop. Weeghman rhapsodized, “It remains a haunting, indelible experience that got me as close to Birdsville as I ever expect to get.”

In June 1974 at the Reading Air Show in Pennsylvania, Bede unleashed a three-jet aerobatic team of BD-5Js that upstaged the Blue Angels with, among other stunts, quadruple vertical snap-rolls. That day may have been the zenith of Bede hype, the last gasp of fantasy before reality started to set in.

That same month, Burt Rutan resigned. “I didn’t want to be around when he went bankrupt and the lawsuits started,” Rutan says now.

The engine woes continued. Bede worked closely with Hirth to build an engine specifically for the BD-5, but the underlying problem was that airplanes are different than snowmobiles. “We broke every part of the engine on the test stand,” Les Berven later admitted. “Rings, cylinders, pistons, bearings, crankshafts. Everything went at one time or the other.”

At about the same time, the ever upbeat (delusional? lying?) Jim Bede wrote in “Bede News,” Vol. 1 No. 3, “We have completed all testing of the BD-5.”

By the summer of 1974, a new prototype of the prop-driven plane, N503BD, was finally deemed ready to be flown by journalists, although the engine had to be pull-started by hand like a lawnmower and would stop dead if the plane encountered turbulence. I was lucky (?) enough to be invited, despite my meager 400 hours flying time.

Slipping into the tiny cockpit, I felt as if I were pulling on an aluminum body suit (or perhaps climbing into a coffin). Instead of the normal control wheel or stick, there was a tiny joystick control on the right armrest—just like the YF-16, the revolutionary new Air Force fighter prototype that had recently made its first flight.

I lack the words to describe the half-hour of giddy dream fulfillment that followed. N503BD was extremely stable, yet responsive to a flick of the wrist. I indeed felt as if I were soaring among the birds, albeit at only 170 mph, not 270. Forty-five years later, it still rates as the peak moment of my flying career.

Not long after my flight, Hirth went bankrupt. At that point it dawned on me that my dream might never be realized. I’d been plugging away in my barn workshop for almost two years, and had a beautiful set of wings, a fuselage shell and a vertical stabilizer. But many of the kit parts and materials—including, of course, the engine—had not been delivered.

With his cash flow dwindling, Bede turned his focus to the FAA-certified airplane, leaving us homebuilders feeling abandoned. Worse, he was also spending money—our money—developing two new projects, the BD-6 and BD-7. A new engine from the Japanese manufacturer Xenoah was tested, with the usual results: many promises, no reality.

By mid-1976, I had concluded the BD-5 was doomed, and sold my partially completed kit. I’d put $3,500 and 400 hours of labor into the project, but felt lucky to get $1,500 for it. (I recently heard from the fellow who bought it; the pieces remain in his basement, untouched to this day.) Looking back, I had probably done no more than 10 percent of the work to complete the job. Even with all the parts, it’s now obvious I lacked the skills and determination to ever finish it.

In November 1976, the 503 prototype was destroyed in a crash. Bede Aircraft Corp. was by then a dead company walking. Having burned through some $7 million in kit payments and $2.7 million in production model deposits, it had no money left to build a new prototype, produce kit parts, find an engine or pursue FAA certification of the BD-5D. Multiple attempts to secure financing foundered, and bankruptcy mercifully arrived in 1979. Accused of fraud by the Federal Trade Commission, Bede signed a consent decree promising to not accept money for any aircraft project for a period of 10 years.

(Ten years later, almost to the day, Bede announced the BD-10, intended to be the world’s first supersonic homebuilt. Five examples were built and three crashed, killing their pilots. None ever got close to supersonic speeds. In 1995 Bede began taking deposits for the BD-12, a two-seat version of the BD-5 with a standard aircraft engine. It crashed on its first flight attempt. Jim Bede died of natural causes in 2015.)

In the four decades since Bede’s bankruptcy, an estimated 150-200 determined and resourceful BD-5 builders have managed to complete and fly improvised planes. BD-5s have flown with Honda Civic, Volkswagen and Subaru engines; Mercury outboards; Wankels; Rotaxes; and even an updated version of the accursed two-cylinder Hirth that seems to run just fine. There was a turboprop version, powered by a gas generator from a Chinook helicopter. Perhaps 50 BD-5s are currently airworthy worldwide.

Almost as many have crashed and killed their pilots. The Aviation Safety Institute database shows a total of 25 fatal BD-5 crashes—12-15 percent of all BD-5s that ever flew. Many occurred on the first flight of newly finished aircraft, with engine failures and subsequent stalls a common thread. Of the first four homebuilt BD-5As, a version with shorter wings, three crashed and killed their builders on their first takeoffs. The fourth survived long enough to crash on its first landing.

I’ve always been puzzled by this rash of fatal crashes. The plane I piloted was easy to fly, with dead-on pitch stability. Its stalls were gentle and predictable, with instant recovery when back-pressure on the stick was released. Yet the same plane I flew, N503BD, later stalled and crashed. I still don’t get it.

Perhaps poor workmanship degraded the flying qualities of some customer-built planes. And most homebuilt BD-5s, with their bulkier engines, were much heavier than the factory prototypes, which increased stall speeds. The heavier engines may also have caused center-of-gravity problems; the BD-5’s safe CG envelope was literally a matter of inches. But one thing is clear: An amateur pilot with less recent practice in flying than building has no business in the cockpit for the first flight of a homemade airplane with a kludged-together engine. That’s a job for a professional test pilot—and a very brave one at that.

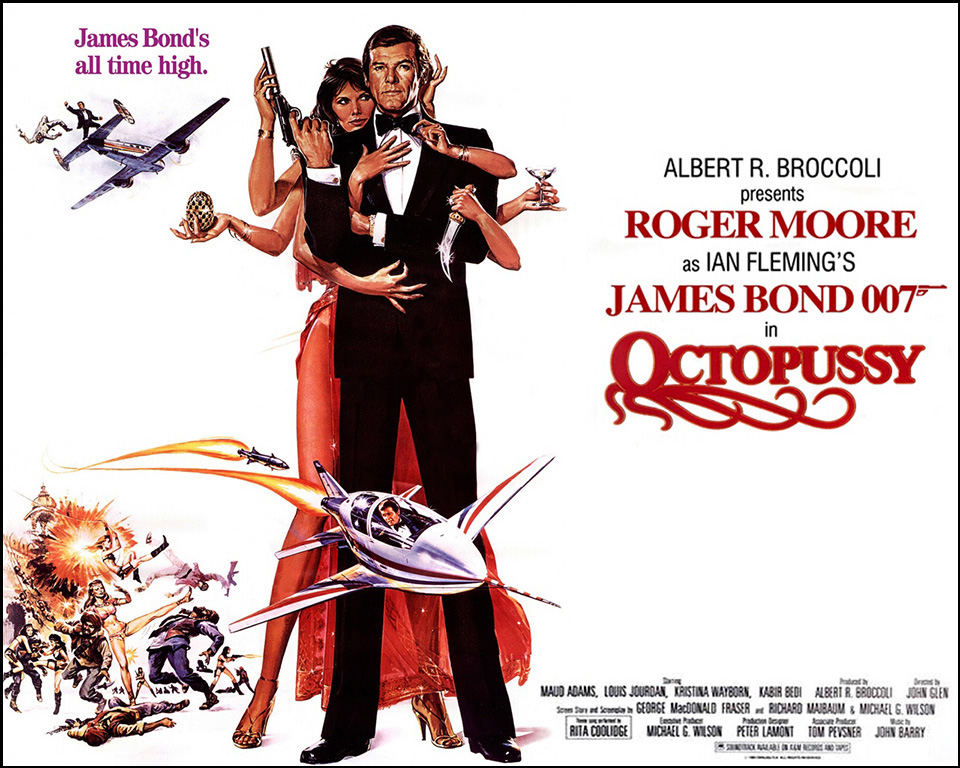

The BD-5J, with its more reliable jet engine, has been by far the most successful Micro. (Who can forget James Bond’s miraculous jet escape in Octopussy?) About 25 BD-5Js have flown over the years, mostly as aerial stunt planes for purveyors of liquid refreshment. A dozen or so Microjets are currently active.

Surprisingly, pilots newly smitten with BD-5 fever can still pursue their fantasies. A company called BD-Micro Technologies, in Siletz, Oregon, has decades of BD-5 experience and a stockpile of original Bede kit parts. It makes all the missing pieces (with many design improvements) and has set up construction tooling and jigs. An aspiring BD-5 builder can today, after writing a check for about $90,000 and putting in 200-300 hours of supervised hands-on labor at BD-Micro’s production facility, fly away in a new, Hirth-powered BD-5 that’s way better than the original.

Believe me, I’m tempted.

David Noland is a former editor at Air Progress and Aviation Consumer magazines now drifting into semi-retirement. He currently flies only in his imagination. For more information on BD-Micro Technologies, see bd-micro.com.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2020 issue of Aviation History.