In the 1960s as Americans began to hear more and more about a place unfamiliar to most of them, they were also learning the name of a man added to a growing list of leaders carrying the banner of communism and threatening Western ideals after World War II. The country was Vietnam, and the man was Ho Chi Minh, who led communist-controlled North Vietnam and wanted to take over South Vietnam to create an independent, unified communist country.

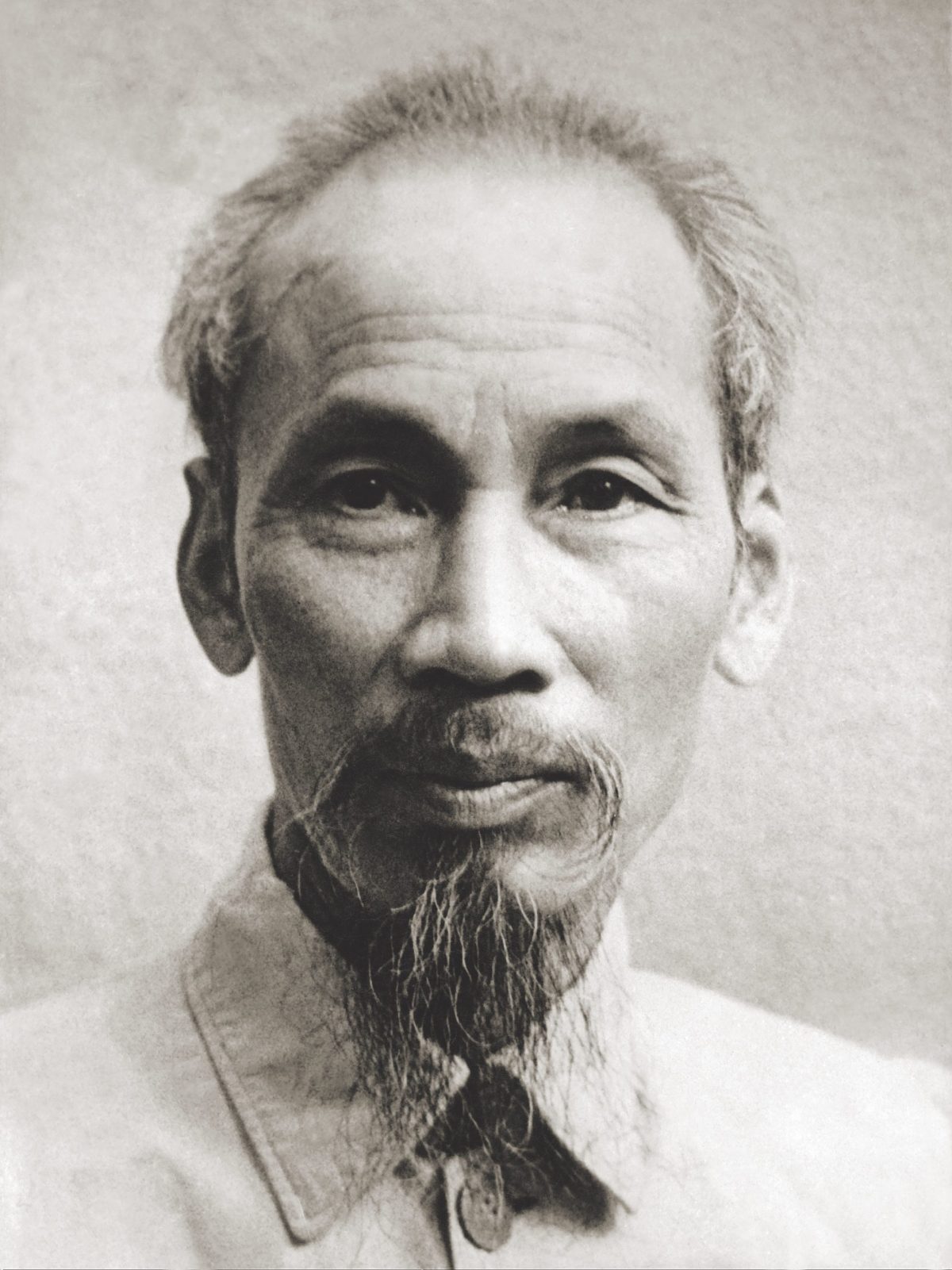

Although Ho’s name was largely unknown to Americans, he had been arguing for—and then fighting for—independence since the end of World War I. By the time the first U.S. combat units arrived in South Vietnam in March 1965, Ho was nearly 75 years old and would not get to see the last U.S. troops leave in March 1973. Ho died in September 1969.

Fifty years later, many Vietnamese still revere “Uncle Ho,” as he is affectionately called, for his relentless pursuit of independence. (U.S. troops in Vietnam also called him “Uncle Ho,” but mockingly.)

In forming his arguments for independence, theories of warfare and plans for a new social system in Vietnam, Ho drew on his own experiences and philosophies from the diverse array of cultures that he had studied.

Ho’s publicly espoused views meshed the tenets of Confucianism, the ideals of independence and freedom championed in democracies, and the common ownership characteristic of Marxist communism. He hoped those principles would inspire revolutionary fervor in the Vietnamese, while a concerted propaganda campaign instilled fear in opponents and weakened their will to endure a long war.

Ho acquired much of his knowledge of the East and West by living in both. He learned French, English, Russian and Chinese.

Born Nguyen Sinh Cung on May 19, 1890, in Kim Lien in Nghe An province in central Vietnam, he began using Ho Chi Minh (“Ho the Enlightened One”) around the early 1940s. Ho was immersed in Confucian beliefs, which emphasize loyalty, respect and “collective independence”—a focus on the independence of a society overall rather than the independence of the individual members of that society.

He left Vietnam in 1911, at age 21, to visit France, the colonial power that had conquered Indochina in the mid-to-late 1800s. That travel adventure also took him to New York and Boston (1912-13), then back to Europe for a stay in London before returning to France, where he attended the 1919 Paris Peace Conference at Versailles after World War I and promoted independence for Vietnam. While living in France, England and the United States, Ho had seen democracy and representative government at work.

Ho also studied—and came to embrace—the alternative political philosophies of socialism and communism promoted in the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He saw governments operating under those philosophies in the 1920s while he spent time in Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik-controlled Soviet Union and in China, where a Communist Party had formed and Mao Zedong was an emerging leader.

Paul Mus, a French author of books on Vietnam, quotes Ho as saying: “When I was young I studied Buddhism, Confucianism, Christianity as well as Marxism. There is something good in each doctrine.” To American journalist Robert Shaplen, Ho stated simply: “I am a professional revolutionary.”

During the 1919 Versailles conference, Ho presented a petition with a list of eight demands in accordance with the right of self-determination. The document had echoes of the American Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights as well as the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. Ho argued that as long as Vietnam was a colony of France, the Vietnamese should have the same rights that French citizens have. His petition was ignored.

Ho came to see a Marxist revolution as the route to independence. His tone toward Vietnam’s colonial occupier became more strident. In a speech at Tours, France, on Dec. 26, 1920, during a congress of the French Socialist Party, which voted to become the French Communist Party, he stated:

In [France’s] selfish interests, it conquered our country with bayonets. Since then we have not only been oppressed… shamelessly, but also…poisoned pitilessly. Plainly speaking, we have been poisoned with opium, alcohol, etc. I cannot, in some minutes, reveal all the atrocities inflicted on Indochina…. We have neither freedom of press nor freedom of speech…. We have no right to live in other countries or to go abroad as tourists. We are forced to live in utter ignorance and obscurity because we have no right to study…. Such is the treatment inflicted upon more that 20 million Vietnamese…. And they are said to be under French protection!

Ho understood that the average person in France knew nothing of Vietnam, so he tried to gain support through stories about the harsh treatment the Vietnamese received.

In Le Paria, a magazine Ho founded in France in 1922, he wrote that French soldiers entering a village found two old men and two women with a baby and a little girl. The soldiers demanded money, brandy and opium. “Becoming furious because nobody understood them,” Ho wrote, “they then beat one of the old men to death … roasted the other old man over a fire of twigs. Meanwhile, the rest of the group, having raped the two women, followed … the little girl and murdered her.” In response, French Indochina Governor-General Pierre Marie Antoine Pasquier (in office 1928-34) issued an apology to Ho and the Vietnamese people, promising better behavior—but not a withdrawal from Vietnam.

Ho studied Lenin’s theses on “National and Colonial Questions,” which cast Marxist revolutions as not just revolts against capitalism but also as rebellions against colonial empires. After Lenin’s death on Jan. 21, 1924, Ho wrote in the Communist Party newspaper Pravda that Lenin, “after having liberated his own people” during the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, “wanted to liberate other peoples too. He called upon the white peoples to help the yellow and black peoples to free themselves from the foreign aggressors’ yoke.”

Ho, who attended the Fifth Congress of the Comintern (Communist International organization) in Moscow in June 1924, praised Lenin again in 1926, writing in the French magazine Le Sifflet, “Lenin was the first to realize and assess the full importance of drawing the colonial peoples into the revolutionary movement. He was the first to point out that, without the participation of the colonial peoples, the socialist revolution could not come about.”

Writing for the Soviet publication Problems of the East in 1960 Ho stated: “At first, patriotism, not yet Communism, led me to have confidence in Lenin…. By studying Marxism-Leninism parallel with participation in practical activities, I gradually came upon the fact that only Socialism and Communism can liberate the oppressed nations and the working people.”

Ho, who entered political life as a nationalist seeking independence for Vietnam, had decided fairly early in his quest that communism was the philosophy best-suited to achieve his goal. He founded the Vietnamese Communist Party in Hong Kong on Feb. 3, 1930, long before he presented himself to World War II’s Western Allies as simply a “Vietnamese nationalist.”

He said in a written message to the party on Feb. 18, 1930, that in the growing opposition to French rule “workers refuse to work, the peasants demand land, the pupils strike, the traders boycott,” adding that “while the French imperialists are frenziedly carrying out terrorist acts, the Vietnamese Communists…have now united into a single party.”

Once independence was gained, Ho said in that message, his Communist Party would establish a worker-peasant and soldier government; confiscate businesses and plantations so they could be distributed to peasants; implement an eight-hour work day; abolish public loans, waive unjust taxes; give the masses freedom; implement universal education; and establish equality between men and women. Essentially, these were the same desires touted, then quashed, by Lenin’s Bolsheviks in 1917-18.

By July 1939, the Vietnamese Communist Party’s democracy program, presented by Ho at a Comintern meeting in Hong Kong, included freedom to organize and assemble, freedom of speech and freedom of political thought.

After German troops overran France in 1940, the Japanese took control of French Indochina but kept the administration in French hands. Ho realized he would now have to fight both the French and Japanese.

In January 1941, Ho wrote a pamphlet, “The Road to Liberation,” which outlined a two-week training course for young cadres. It covered utilizing mass organizations, methods of propaganda and organization, training and revolutionary struggle.

Then in May, Ho and other Vietnamese communist leaders formed the Viet Minh, an organization that also included noncommunist nationalists, to fight for independence. At a meeting that month of the Central Committee of Vietnam’s Communist Party, Ho trumpeted: “Compatriots throughout the country! … Rise up quickly … to fight the French and the Japanese.”

Ho believed he could win independence if the Vietnamese people felt that the fight was for freedom, justice and equality—achieved through the vehicle of communism.

Ho thought the teachings of Confucianism could also assist him. Confucianism teaches that everyone can attain a “superior person quality,” and Ho felt that each soldier and citizen could attain that quality.

The traits of this superior person include enlightenment, philanthropy, friendship, returning good for evil, consistency, respect for the majority’s wishes, a desire for learning, and an awareness of wealth without virtue and virtue without wealth. Ho also believed that if the Vietnamese thought he had attained the qualities of a superior person, they would eagerly join his revolutionary forces.

Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945, ending World War II, and signed the surrender papers on Sept. 2, 1945. That same day, Ho issued the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence, whose first words duplicated the “all men are created equal” passage in the American declaration. “This immortal statement was made in the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America in 1776,” Ho’s declaration proclaims. “In a broader sense, this means: All the peoples on the earth are equal from birth, all the peoples have a right to live, to be happy and free.”

Ho knew, however, that the end of World War II would not bring automatic independence. Even before the war was over, the Allied powers had decided to return Vietnam to French rule. By early 1946, France was back in control of Vietnam.

Ho wrote President Harry S. Truman on Feb. 15, 1946, to request the U.S. support for Vietnam’s independence:

Our Vietnam people, as early as 1941, stood by the Allies’ side and fought against the Japanese and their associates, the French colonialists…. But the French Colonialists… have come back and are waging on us a murderous and pitiless war…. we request of the United States as guardians and champions of World Justice to take a decisive step in support of our independence.

Truman did not respond. Rising tensions between the French and Vietnamese spun into a full-fledged war that began on Dec. 19, 1946.

In a message to the Vietnamese people on Dec. 21, 1946, Ho said the Vietnamese had an affection for France because they both held common ideals of freedom, equality and independence. But that relationship was ruined by the French colonialists who took profit from Vietnam and treated the natives as inferiors. Then Ho addressed the French soldiers directly: “Can you be content with sacrificing your bones and blood and your lives for the reactionaries?… The Resistance War will be long and fraught with sufferings. Whatever sacrifices we have to make and however long the Resistance War will last, we are determined to fight to the end.”

Ho knew his enemies wanted to fight a “lightning war,” but for him the cause was greater than any individual life. Ho explained in a November 1945 speech that “we are determined to sacrifice even millions of combatants and fight a long-term war of resistance in order to safeguard Viet-Nam’s independence.” And in a message to his people on Dec. 20, 1946, he elaborated on the cost, saying the Vietnamese must “sacrifice even our last drop of blood to safeguard our country.”

Following the success against the French in the second Hong Phong Campaign of Sept. 30 to Oct. 18, 1950—in which the Viet Minh cleared a route to the Chinese border and inflicted about 8,000 casualties on their enemy—Ho listed six tenets of war: 1) heighten discipline; 2) strictly carry out orders; 3) love the soldiers; 4) respect the people; 5) take good care of public property and war booty; 6) sincerely make criticism and self-criticism. He also added three factors for winning: 1) terrain conditions; 2) people’s support; 3) time ranges.

Ho believed guerrilla tactics were essential. After Japan occupied Indochina in 1940, he built a Sino-Vietnamese alliance to establish a united front and a base for guerrilla activities. Ho wrote an instruction manual on the tactics of guerrilla warfare. Ho knew his army was weak, so his soldiers had to be trained in guerrilla tactics that would wear down their opponents and enable the Vietnamese to make an all-out offensive when the time was right for a total victory.

Guerrilla warfare “consists in being secret, rapid, active, now in the East, now in the West, arriving unexpectedly and leaving unnoticed,” he wrote at the establishment of Vietnam Propaganda Unit for National Liberation in December 1944.

Enough guerrilla units must exist throughout the country to create “an iron net” so that “wherever the enemy goes he will be enmeshed,” Ho stated in a political report read at the Second National Congress of the Vietnam Workers Party in 1951. Guerrilla units included not only young men but also old men, women and youth.

But Ho realized that complete victory could only be obtained by a large, determined force. In his instructions for the propaganda unit, he said: “To act successfully, in the military field, the main principle is concentration of forces.” The men would be picked from the ranks of the guerrilla units in the provinces, and “a great amount of weapons will be concentrated to establish our main force.”

Ho’s forces won their war with France on May 7, 1954, in a stunning defeat of French soldiers at Dien Bien Phu in the northern part of the country. An agreement reached in July 1954 at a conference in Geneva ended France’s rule and split the country into North and South Vietnam. But Ho, head of the government in the North, still sought a unified Vietnam, and by March 1965 he would be at war with U.S. combat units supporting South Vietnam.

As the military fight wore on, so did the philosophical struggle between democracy and communism. Since Ho had lived in democratic societies, he believed some elements of democracy would work in conjunction with communism, and for a period he allowed more freedom of speech.

Publications such as the Nhan Van (Humanities), published between 1955 and 1957, and the Giai Pham (Masterpieces), 1956 to 1957, voiced criticisms of the party. However, in 1956 Ho abruptly reversed his professed democratic policies and cracked down on those publications as well as professors and other outspoken citizens,

Ho had concluded that communism and democracy were antonyms and that only one could survive. Pierre Asselin in Vietnam’s American War suggests Ho may have allowed democratic reforms only to expose enemies of the party, but he argues that it was more likely Ho believed democratization could work but underestimated its effects.

Three years after Ho’s death in 1969, Truong Chinh, who was Ho’s second in command 1941-57, stated that a mix of communism and democracy would be the common mission of the North and South Vietnamese. The North was to continue the socialist revolution and the South was to “sweep away the U.S. imperialists aggressors … and win back national independence and democracy for the people.”

Today, Vietnam is still the centrally controlled communist dictatorship that Ho created, but it has a Western capitalist economy that is thriving.

Arguably Ho’s greatest military theory concerned the effective use of propaganda to break the opposing side’s will. At the Comintern Congress in Moscow in 1924, Ho complained to the assembled body about a lack of emphasis on propaganda: “Why is it that where the revolution is concerned you do not wish to make your strength, your propaganda, equal to the enemy whom you wish to fight and defeat?”

Ho, always ready to be his own propagandist, never shied from an interview. On Aug. 13, 1963, he spoke to Wilfred Burchett of the National Guardian and the Algerian Revolution Africaine:

A savage war is being waged against our compatriots in South Vietnam …. U.S. pilots are daily bombing and burning peaceful villages, destroying food crops and orchards with noxious chemicals …. The U.S. directed military-political aims at present are to herd the entire population in the countryside of South Vietnam into concentration camps …. [T]ens of thousands had been massacred in cold blood and hundreds of thousands more herded into the slow death.

Replying to the American magazine Minority of One in May 1964, Ho pitted the American people against their government:

This so-called “special war” is actually a war of aggression waged by the U.S. Government and its agents, a war which is daily causing grief and suffering to our fourteen million compatriots in South Vietnam, and in which thousands of American youths have been killed or wounded … . The Vietnamese people are well aware that the American people want to live in peace and friendship with all other nations. I have been to the United States, and I understand that the Americans are talented people strongly attached to justice… The Vietnamese people never confuse the justice-loving American people and the U.S. Government.

The United States, Ho said over Radio Hanoi on July 17, 1966, “may bring in 500,000 troops, 1 million, or even more to step up the war of aggression in South Viet-Nam. They may use thousands of aircraft for intensified attacks…. But never will they be able to break the iron will of the heroic Vietnamese people…. The war may still last ten, twenty years or longer … our people and army … will resolutely fight until complete victory.”

Ho’s army was never the strongest, but he always outlasted the opposition by weakening their resolve.

By March 1973, more than two decades after the first U.S. military advisers came to Vietnam in 1950, all U.S. troops were out of the country. In April 1975, after the fall of Saigon and six years after Ho’s death, North and South Vietnam were united into a single country. Ho’s military theories and tactics had proved successful.

Joel Kindrick has a master’s degree in military history from Norwich University and was an instructor of history, government and language at Pepperdine University, California Lutheran University and Pacific Union College. He has done extensive interviews with veterans of American wars.