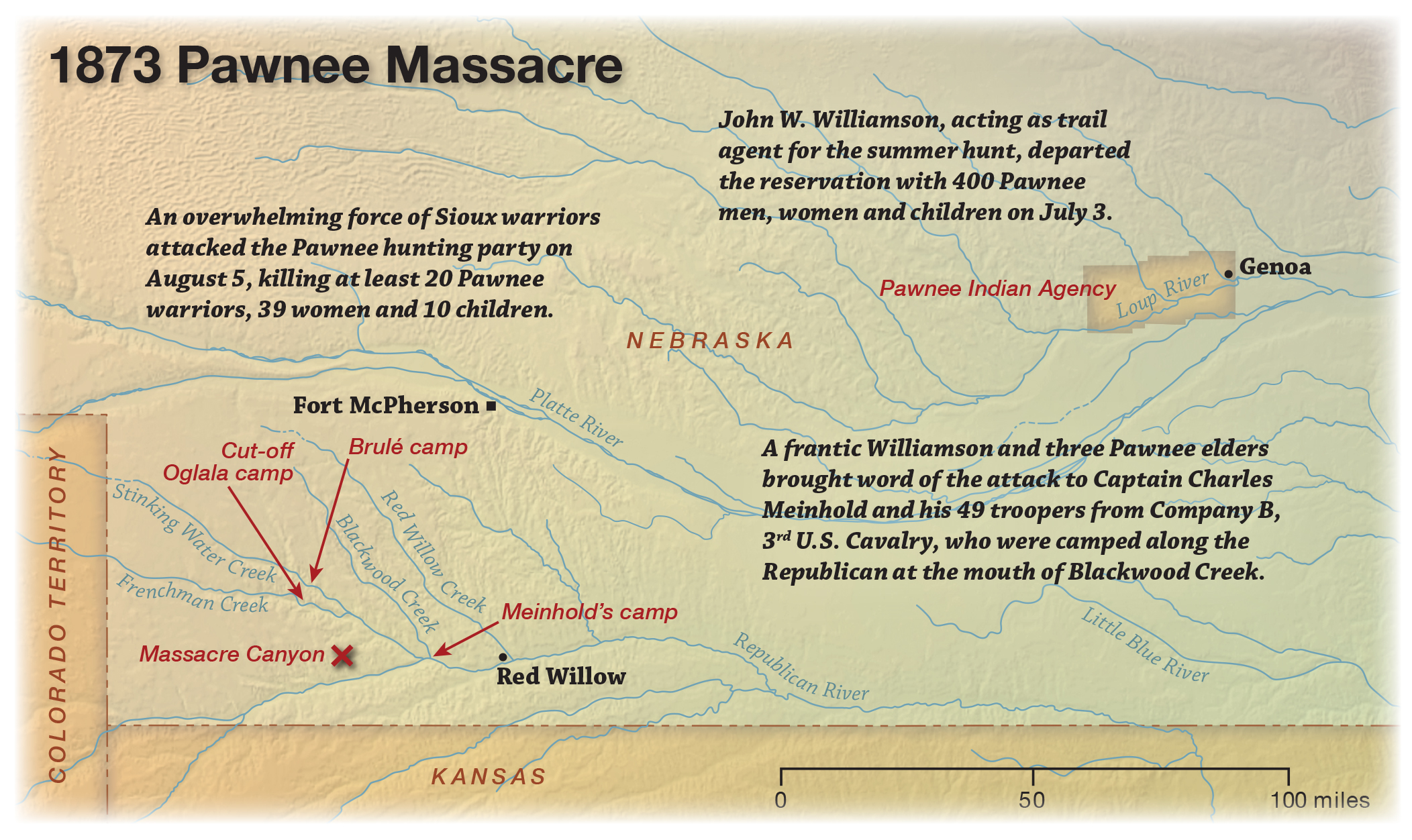

Captain Charles Meinhold may well have hoped to complete his assignment without incident as he led the sweat-stained troopers of Company B, 3rd U.S. Cavalry, plodding methodically across the monotonous broken plains of southwest Nebraska. Tasked to monitor nominally peaceful reservation Indians then hunting in the area, Meinhold’s patrol along the Republican River also served to curb rowdy frontiersmen and protect surveyors then busily delineating homesteads for white settlers. There was little relief from the oppressive heat and humidity during the tedious march. Five days of probing south from Fort McPherson had proved uneventful. But as the soldiers busied themselves about camp at the mouth of Blackwood Creek on Aug. 5, 1873, Meinhold’s routine patrol unraveled.

Galloping frantically toward the troopers late that morning were a young white man and three Pawnee elders bearing shocking details of a brutal massacre just upriver. Underscoring their agitation, a column of blood-spattered, bedraggled refugees slowly staggered into view from the west. As Meinhold struggled to comprehend their anguished accounts, it became clear an overwhelming force of Sioux (Lakota) warriors had attacked the hapless Pawnees, slaughtering several men alongside many women and children.

Although the vicious attack had left the Pawnees dazed and demoralized, their chiefs assured Meinhold they could rally to counterattack the Sioux, if only the soldiers would assist them. The captain wisely declined, explaining that his 49 troops could accomplish little against the host of warriors the chiefs had described. He advised the Pawnees to continue down the Republican and regroup near the settlement of Red Willow, some 20 miles farther east, while he investigated.

Troopers approached a shallow canyon that contained the first bloody evidence of the brutal struggle—mutilated bodies that lay as they had fallen, filling the canyon with a reeking carnage

After a westward march of a dozen miles, Meinhold’s troopers approached a shallow canyon that contained the first bloody evidence of the brutal struggle—mutilated bodies that lay as they had fallen, filling the canyon with a reeking carnage. Meinhold’s worst fears were confirmed.

Civilian contract surgeon David F. Powell later wrote of his own pained reaction:

It was a horrible sight. Dead braves with bows still tightly grasped in dead and stiffened fingers; sucking infants pinned to their mothers’ breasts with arrows; bowels protruding from openings made by fiendish knives; heads scalped, with the red blood glazed upon them—a stinking mass, many already flyblown and scorched with heat.

Green troopers may have vomited as they probed the silent, gore-spattered gully. Among the bloating corpses, thousands of pounds of jerked bison meat and hundreds of furs lay strewn in disarray, testifying to the panic sparked by the sudden and murderous Sioux attack.

The clustered earth lodges of the Pawnees, who had tentatively accepted reservation life as early as 1857, made tempting and easy targets for their nomadic Sioux enemies. As they sought to walk the white man’s road, the Pawnees soon learned that federal promises of protection meant little in the face of persistent incursions by Brulé and Oglala raiders.

Despite their sedentary appearance, the Pawnees by necessity ventured off the reservation to supplement their meager crops and uncertain annuities with meat gathered during two broad-ranging annual buffalo hunts. President Ulysses S. Grant’s recently appointed Quaker Indian agents deplored the practice, which they believed permitted the Pawnees an unwarranted freedom from agency control.

The Quakers demanded an unrealistically rapid and uncompromising transformation of the Pawnees’ lifestyle. By 1873, however, the grim realities of reservation life had left the tribe nearly destitute. Although their previous summer hunt, shepherded by Buffalo Bill Cody associate John B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro, had temporarily replenished their larders, the subsequent unchaperoned winter hunt had ended poorly when Sioux raiders stole more than 100 of their horses and scattered the Pawnees, forcing them to cache their meat, walk back to the agency and endure a humiliating and hungry winter.

Following a grand council that spring, Pawnee leaders eagerly anticipated the forthcoming summer hunt, even though the nearest buffalo herds were upward of 150 miles away. Omohundro reportedly applied for the 1873 trail agent position, but he found the prospect of appearing onstage in New York City with Cody too tempting to turn down. Or perhaps it was his costar, Italian dancer Giuseppina Morlacchi, he found so alluring—enough to marry her that summer. Regardless, Texas Jack was unavailable.

The previous winter Quaker William Burgess had assumed control of the Pawnee Indian Agency at Genoa, near Columbus in eastern Nebraska. Luther North, of the famed Pawnee Scouts, rated the incoming agent as wholly unqualified, noting, “His judgment, where the Pawnee are concerned, if anything is poorer than any of the other agents the Pawnees have had.” Shocked by the tribe’s starvation and poverty, Burgess at first sought early distribution of annuity goods for his starving wards. By June, however, he had reluctantly authorized the summer hunt. Sixty-year-old Sky Chief, considered among the ablest of the Pawnee leaders, would be in charge, aided by Sun Chief and Fighting Bear.

That spring John W. Williamson, a 22-year-old homesteader from Wisconsin, had signed on at Genoa as an agency farmer, or “agriculturalist.” The genial farmer was well-liked by the Pawnees, who named him “Curly Head,” due to his shoulder-length wavy brown hair. Of Norwegian descent, he was in excellent physical condition and spoke passable Pawnee. Despite Williamson’s good press, North gave him mixed reviews, dismissively charging that the Scandinavian agriculturist knew no more about the Pawnees than did the Quaker agent. North did admire Williamson’s pluck, though, asserting he “showed himself a man all the way.”

Pawnee leaders urged Burgess to appoint the longhaired farmer as trail agent for the summer hunt. As Williamson hadn’t applied for the position, he was surprised when a chief informed him of his appointment. He undoubtedly knew less about being a trail agent than Omohundro did, a deficiency the tribal elders may have hoped would result in less stringent oversight. In defining his responsibilities, Burgess cautioned Williamson to avoid interfering with the Pawnees’ traditional mode of hunting, while authorizing him to provide such counsel as he saw fit in all other matters. Ominously, the agent also warned Williamson to guard against incursions by the tribe’s traditional enemies.

Lester Beach Platt, a young man out from Baltimore to visit his Indian trader uncle, asked to join the hunt. Feeling he might prove good company, Williamson consented, though he suspected the young man might be a tenderfoot of the first degree. Platt confirmed the trail agent’s suspicions during their first buffalo chase on nearly being thrown from his horse and trampled. The Pawnees called the young man Keats-ko-toose Kittabutsk, which translates roughly as “Little Platte River,” a play on both his surname and his relationship to the older Platt at the agency.

In 1873 the agency at Genoa supported upward of 2,300 Pawnees, including some 600 warriors. Of these, 250 men left the agency on July 3, accompanied by 100 women and 50 children. Most of the men were armed with bows and arrows, their preferred and most efficient hunting weapons. Others carried obsolete muzzleloading muskets, while a few had obtained seven-shot Spencer carbines or percussion revolvers. The Pawnees were thus well armed for hunting if woefully unequipped for battle.

Though ragged, their pageant presented a dramatic spectacle, sweeping across the prairie in a column that stretched nearly a mile. Curious white settlers gathered along the route to marvel as they passed.

For a month the Pawnee hunt proved successful, reaping a harvest of some 800 animals. Both Williamson and Platt described the process as well-organized and efficient. Nights often featured joyous feasts Williamson compared favorably to Christian prayer meetings. In the wake of the first hunt the trail agent endeared himself to his Pawnee colleagues by wolfing down a blood-sopped slab of raw buffalo liver.

The evening of August 4 found the Pawnees camped along the north bank of the Republican River. With the hunt winding down, they made preparations to begin their return trek to the agency the following morning. Around 9 that night John Deary and two fellow buffalo hunters stopped by camp to warn the hunting party that a large band of Sioux was camped 25 miles to the northwest, seemingly bent on attacking the Pawnees.

In response to an earlier warning Williamson had enforced a precautionary detour, a move that had only irritated the Pawnee hunters when they encountered neither Sioux nor buffalo. Understandably, they greeted news of this latest warning with great skepticism. Sky Chief wasted little time in denouncing the buffalo hunters as liars who sought to frighten off the Pawnees in order to slaughter the animals themselves for their hides. When Williamson again counseled caution, Sky Chief flew into a rage, denouncing the young field agent as a woman and a coward. His ego stung, Williamson barked back: “I will go as far as you dare go! Don’t forget that.”

Meanwhile, in the Sioux camps, a party of warriors from the Cut-off band, led by Oglala Chiefs Little Wound and Pawnee Killer, had reported sighting the Pawnee hunting party. Little Wound decided to attack immediately from his camp on Frenchman Creek. Smarting from recent losses to Ute horse thieves, Pawnee Killer was also ready for a fight. It had required every bit of diplomacy possessed by their own trail agent, Antoine Janis, to prevent the Sioux from mounting a bloody reprisal against the Utes. They would not be denied again.

With their inveterate enemies nearly in hand, Little Wound demanded to know whether his warriors were free to attack them. Janis demurred. While he forbade attacks on the Pawnee reservation or near white settlements, he cryptically left the present question hanging. Little Wound haughtily responded that as Janis had quashed the reprisal against the Utes, the young Sioux warriors would no longer listen to the trail agent.

As the Cut-offs prepared for battle, they dispatched runners to Spotted Tail’s Brulé camp, upstream on Stinking Water Creek. In 1872 Spotted Tail’s band, as a peaceful gesture to whites, had entertained Russia’s Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich during Cody and Lt. Col. George Custer’s extravagant winter buffalo hunt only a few miles away. It is uncertain whether Spotted Tail personally joined the gathering war party against the Pawnees, though he likely refrained. Stephen F. Estes, trail agent in charge of the Brulés, later asserted, “I used every effort to induce the Indians under my charge to make peace with the Pawnees…but the young men would listen to nothing.”

In the predawn darkness of August 5 Pawnee scouts spotted some 50 head of bison near their line of march. The hunters promptly galloped off for one last chase, leaving their women, children and older men to press eastward with the pack animals. Some noted a distant mass of dark, moving objects, suggesting an even larger herd.

As they rode along, a remorseful Sky Chief apologized to Williamson for his outburst the previous evening. Still convinced the white hunters had lied, however, the Pawnee chief had neglected to send scouts toward the reported Sioux encampment. The last time Williamson saw Sky Chief was when he rode off to join the chase.

On sighting the buffalo, one young Pawnee begged to borrow Williamson’s rifle and raced away with it to join the hunt. Williamson never saw the young man or the rifle again.

The pack train had nearly eased out of sight to the east when Williamson noted a commotion near the head of a small canyon. He spurred forward, discovering to his alarm Sioux warriors were approaching. Women’s war chants and wailing rose from the canyon as Pawnee warriors rallied to screen them.

Waging the initial attack was a Sioux vanguard of perhaps no more than 100 warriors. Nevertheless, they slammed into the Pawnees with a shock and surprise that enabled them to kill the few hunters who had dismounted to begin skinning slain buffalo. Among the latter was the heedless Sky Chief, who was surrounded and died fighting as he tried to reach his horse.

In the initial confusion Williamson urged the Pawnees to retreat down canyon to a stand of timber that offered a more promising defensive position, but Fighting Bear angrily disagreed, insisting the warriors hold their ground. He had often fought the Sioux and trusted his men could whip them in an open fight. With no time to argue, the Pawnees deployed to defend themselves where they stood, skirmishing bravely for perhaps an hour.

Having failed to sell a retreat, Williamson felt duty bound to forestall the Sioux onslaught by himself, if possible. Riding to within 300 yards of the onrushing hoards, the agent and a companion wildly waved white handkerchiefs to draw the attackers’ attention.

As the Sioux thundered toward them, Williamson recalled an elderly lady friend who had teasingly remarked his long hair would make an attractive scalp

Memories fade, of course, especially under such duress. Within days of the battle Williamson reported he had ridden to the fore with Platt, and in his memoirs the young man confirmed his presence at the outset of the attack. Years later, however, Williamson wrote his companion had been mixed-blood interpreter Ralph Weeks. Still other sources suggest all three men may have advanced.

As the Sioux thundered toward them, Williamson recalled an elderly lady friend who had teasingly remarked his long hair would make an attractive scalp. He later wrote of that terrible realization:

When I saw the Sioux coming, I thought of what the old lady had said, and I did not lose any time in twisting my hair up and tucking it under my hat so it would not be so noticeable.

The Sioux answered Williamson’s peaceful overture with a fusillade of whistling bullets, prompting the agent to whirl his horse and race back toward the Pawnee lines. At the edge of the canyon his mount, struck by one or more bullets, collapsed. Stripping the saddle and bridle from the animal’s corpse, the agent transferred them to his hunting pony and soon rejoined the fight.

Only a few Pawnees lay dead when the main Sioux force arrived, swelling their ranks to perhaps 1,000 warriors. Outnumbered 4-to-1, Williamson’s wards grimly struggled to defend their women, their children and themselves.

Having lost his rifle, Williamson squeezed off shots at the oncoming Sioux with his revolvers. Suddenly, he encountered Fighting Bear, locked in a desperate mounted duel with a warbonneted Sioux, each man slashing wildly at the other with a tomahawk. Williamson fired at the Sioux, wounding him and providing Fighting Bear an opportunity to finish him. Jumping from his horse, the Pawnee chief scalped his adversary and retreated, leading the dead Sioux’s horse down canyon.

As the Sioux reinforcements coalesced around the head of the canyon, Pawnee elders finally ordered a full-scale retreat. Eager to kill their foes, the Sioux arrayed themselves along both walls of the shallow canyon, firing indiscriminately into the writhing mass below. The retreat soon degenerated into a panicked rout, accounting for most of the Pawnee casualties that day.

Caught up amid the calamitous melee, Williamson failed to hear the command to retreat. But as women desperately jettisoned packed meat and scrambled to mount ponies with their children, he realized that he, too, had better run. He later lamented his haste:

I often have thought of a little Indian girl, who evidently had fallen from her mother’s back, in our retreat down the canyon. She was sitting on the ground with her little arms raised, as if pleading for someone to pick her up. As I passed, I tried to pick her up but only succeeded in touching one of her hands. I couldn’t return, so she was left behind to suffer a horrible death.

As the small, scattered groups of Pawnees fled toward the banks of the Republican, the Sioux unexpectedly broke off their pursuit. Those left behind suffered unspeakable horrors. The attackers raped any women who had fallen behind, then killed and mutilated them, though some were undoubtedly still breathing as the Sioux threw their bodies atop pyres of burning robes.

During the frantic withdrawal Platt became separated from the Pawnees and suddenly found himself surrounded. His prospects looked dim indeed when a warrior jumped him from behind to appropriate his revolver. For a moment Platt stared down the muzzle of his own weapon before recalling it wasn’t loaded. At that moment a chief among the Sioux interceded, seemingly deciding it would be impolitic to kill a white man. Released with a rousing round of handshakes, though relieved of his gun, Platt scurried off toward the river. Later that day, as Williamson and the three chiefs briefed Meinhold, the trail agent mistakenly reported the missing Platt’s death.

Williamson worked tirelessly to care for the shattered Pawnees who managed to escape the Sioux wrath, procuring sacks of flour from a store run by Frank Byfield and hiring a homesteader with a wagon to transport a dozen of the wounded. The field agent also wired Indian Affairs Superintendent Barclay White, who arranged for Union Pacific boxcars to transport survivors to Silver Creek, the rail stop closest to Genoa.

A subsequent agency census recorded 20 warriors, 39 women and 10 children slain. The Sioux had taken another 11 children captive, but agents soon arranged for their return. Scores of Pawnees had been wounded, some later dying of their injuries. The Sioux lost perhaps four to six warriors killed and an unknown number of wounded.

The recriminations began almost immediately.

Insisting the Pawnees had been attacked on land they were entitled to use by treaty, Burgess demanded $9,000 in reparations from Sioux annuities for the lost horses, meat, furs and other property. He squarely blamed Oglala trail agent Janis, contending his bungling had clearly established a governmental liability.

Brulé trail agent Estes initially faulted the absent military for the massacre, while Janis simply claimed he had been powerless to prevent the attack. When his attempts to blame the Army failed to gain traction, Estes pointed the finger at Janis:

My failure to avert the attack…was due in a great measure to the ignorance and bad advice given by subagent Janis to the Indians under his charge…[leaving] Little Wound impressed with the idea that he had a perfect right to make war upon the Pawnees.

The slaughter at Massacre Canyon represented only the final chapter in an almost endless litany of bloody, brutal intertribal conflicts that began long before Europeans arrived on the continent

Within months and after much debate the Pawnees reluctantly decided to cede their Nebraska holdings to the United States in return for compensatory reservation lands in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Realizing the government could never adequately protect them, the brokenhearted Pawnees left their ancestral homeland forever.

The slaughter at Massacre Canyon represented only the final chapter in an almost endless litany of bloody, brutal intertribal conflicts that began long before Europeans arrived on the continent. The Army and militia forces of course committed atrocities at such haunted places as Camp Grant, Bear River, Sand Creek, Marias River and Wounded Knee—disgraceful episodes that should never be rationalized, excused or forgotten. Yet the sad fact remains that some of the deadliest massacres of American Indians were perpetrated by rival tribes. Massacre Canyon reminds us that over the course of centuries countless Indians fell victim to such ceaseless and indiscriminate intertribal slaughter. WW

Dennis Hagen retired from the Denver Public Library’s Western History/Genealogy Department as an archivist and special collections librarian and continues to work there as a volunteer. For further reading he recommends The Pawnee Indians, by George E. Hyde; “The Battle of Massacre Canyon,” by Paul D. Riley, published in Vol. 54 of Nebraska History (1973) and available online; and The Battle of Massacre Canyon: The Unfortunate Ending of the Last Buffalo Hunt of the Pawnees, by John W. Williamson.