William S. Love of the 1st Special Battalion of Louisiana Infantry had little time to revel in his army’s victory at the First Battle of Manassas. For nearly three weeks, the Confederate surgeon from New Orleans found himself “constantly employed” treating wounded from both sides at the Carter House, a Manassas hillside homestead now serving as a field hospital. Finally, on August 9, 1861, Love fired off a quick note to his father, apologizing that it had taken him so long to do so. “I have had charge of some thirty or forty wounded prisoners,” he professed. “I got rid of them two or three days ago and have now here only [Captain] George McCausland who had gotten into a conflict wounded in a duel [and] is not in a condition yet to be moved.”

The Civil War’s first major battle on July 21, 1861, had sent a shockwave across both sides of the fractured country. As the clash on the plains of Manassas, Va., teetered on the edge of an expected Union victory that many believed would quell the Southern states’ burgeoning rebellion, fate played its hand, allowing the combined armies of Confederate Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston to storm back and claim a victory.

Hand-picked to win it all, Union Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell attempted a bold advance that morning against the Southern forces assembled both on Matthews Hill and along the Warrenton Turnpike. Buckling under intense pressure on Matthews Hill, Love’s Louisiana Tigers—along with their beleaguered comrades from South Carolina and Virginia cobbled together in Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans’ 7th Brigade—withdrew in disarray toward Henry Hill, where the Southern commanders settled into a defensive posture.

Flush with grandiose visions of victory, McDowell ordered his troops to “press the Confederates.” At midday, astride his horse, he galloped along his lines shouting, “Victory! Victory! We have done it! We have done it!” The Union commander’s euphoric cries, however, produced ill-advised inaction among many of his troops—and soon a Herculean effort by their Confederate counterparts.

Patiently awaiting the Union advance behind a slope near Henry Hill were an unassuming former Virginia Military Institute professor named Thomas Jonathan Jackson and his contingent of Virginia infantry. The subsequent stand by the Old Dominion native would become immortal, of course, as was the Confederates’ remarkable rally on the field, which by evening had the Union troops and hordes of resident bystanders scampering back to Washington, D.C., as fast as the roads would allow.

The Southerners had indeed grasped victory from the hands of defeat.

A Duel… and a Prince

The letters Love finally sent to his father, parts of which are published here for the first time, were heartfelt and in places detailed, particularly his descriptions of the incident involving Captain George McCausland and a visit to the battlefield by Prince Napoleon, the cousin of French Emperor Napoleon III.

Joining Wheat’s Tigers in Colonel Evans’ Brigade at Manassas were the 4th South Carolina; the 30th Virginia Cavalry, Troops A and I; and a section of the Lynchburg (Va.) Artillery. Poor McCausland, a volunteer aide-de-camp on Evans’ staff, had gotten into an altercation with Captain Alexander White, commander of the 1st Special Battalion’s Company B. Only 24, McCausland was a native Louisianan—considered “a strikingly handsome man,” but a little unwise perhaps. White was a notorious character, having once been convicted of murder during a poker game. When McCausland made insulting remarks about the Tigers in the wake of the victory, White was outraged. To satisfy his honor, he challenged the youngster to a duel.

McCausland accepted the challenge, and on July 24 the two squared off near their camp with Mississippi Rifles at “short-range.” White fired first, sending a .54-caliber bullet through both of McCausland’s hips. McCausland, who had fired but missed, languished with the wound in Love’s hospital for more than a month and ultimately perished “in great agony” of pneumonia on September 17. His body was returned to New Orleans for burial at his home in West Feliciana Parish.

Corporal Robert Gracey was among the captured Federals for whom Love also cared at his field hospital. As Gracey later conveyed to a New York newspaper, his two-week stay at the Carter House had been pleasant enough. He revealed that after being wounded he was taken to the hospital “in one of our own ambulances, captured at Bull Run,” and had been “placed…under [the] guard of Lt. Thomas Adrian and his command of Tiger Rifles, of Louisiana.”

The kindly Confederates, Gracey recalled, furnished him with “more condiments, luxuries and personal attentions than were bestowed upon their own sick. Lt. Adrian frequently and jocularly remarked, as an excuse for this, that his object was a selfish one. He wanted to take [him] to the South, and exhibit him, a la [Phineas T.] Barnum, as a fine specimen of the living Yankee who couldn’t be killed.”

As for Prince Napoleon, he did visit the Manassas area in the days following the battle and shared a carriage with Beauregard, escorted by more than 100 cavalrymen under that flamboyant Virginian, Colonel J.E.B. Stuart. According to one unidentified observer, Beauregard and his guest disembarked at the now-famous Stone Bridge and strolled about before returning to their carriage and arriving “on the bare plateau rising above the Bull Run, at the very center of the action, amidst corpses, dead horses and freshly-dug graves.”

The battlefield excursion would end at 11 a.m.

Winter in Virginia

Desperate for news from home to distract him from his exhaustive duties, Love implored his father to direct any letters to him “at Manassas, Wheat’s Battalion. The letters all go addressed to it into our box are taken out and sent as directed.”

“I hope to join the Battalion soon,” he divulged. “[I]t is encamped at Bull Run, where the Battle of the 18th alto [Blackburn’s Ford] was fought. I hear that we are to be kept to the sea, but I hope not.” Love also informed his father that he had sent him “by the Southern Express Company fifty dollars some days ago. I now enclose you the receipt for it lest you might have trouble getting it. I would have sent it long since….[but] the Post Office is at Manassas some eight miles from here and I could not get them to mail a letter….”

By the end of November, Love wrote his father again about the “very cold” weather where he was staying at Camp Florida, outside Centreville, Va. It was something to which the Louisiana native was certainly not accustomed. “I would have obtained a furlough ’ere this to have gone to Richmond probably to New Orleans,” he explained, “but that being in daily expectation of a grand battle with [George] McClellan’s whole Yankee army, I did not like to be absent from the company.”

By mid-December, Wheat’s Tigers were still recuperating their strength. Now camped east of Manassas Junction, they stored their flimsy canvas tents and built more substantial log cabins to weather the increasing winter temperatures. It had been less than a year since they had arrived in Virginia.

Although, as Love noted, offensive actions in the area had halted for the most part as winter approached, he elaborated: “Our scouts report the Yankees to be advancing in immense force. The battle is expected to take place in two days. Whole brigades of our army are sent out on picket duty and daily are capturing bodies of Yankee scouts and foraging parties. We are all sanguine and entertain no apprehensions as to the result. From all accounts it will be a bloody battle. But pray God will give us victory.”

The only “grand” battle of any consequence nearby would be known as the Bog Wallow Ambush, occurring December 4. Tired of Confederates capturing their men, the Yankees began probing enemy positions and finally launched a trap that produced a narrow victory, with five Confederate and four Federal casualties.

Eager for a Fight

The group that had first organized six months earlier at Camp Moore in southeast Louisiana proved a raucous assortment of men. Recruited from the alleyways and docks in the seedier side of New Orleans, they were at least experienced fighters, just not disciplined. While at Camp Moore, a young private from another company, John F. Charlton, wrote in his diary: “Our excitement in camp with the Tiger Rifles was our first experience being often aroused during the night by cries of ‘fall in fall in’ expecting to be attacked by the Tigers. They never liked us because we often accused them of Stealing.”

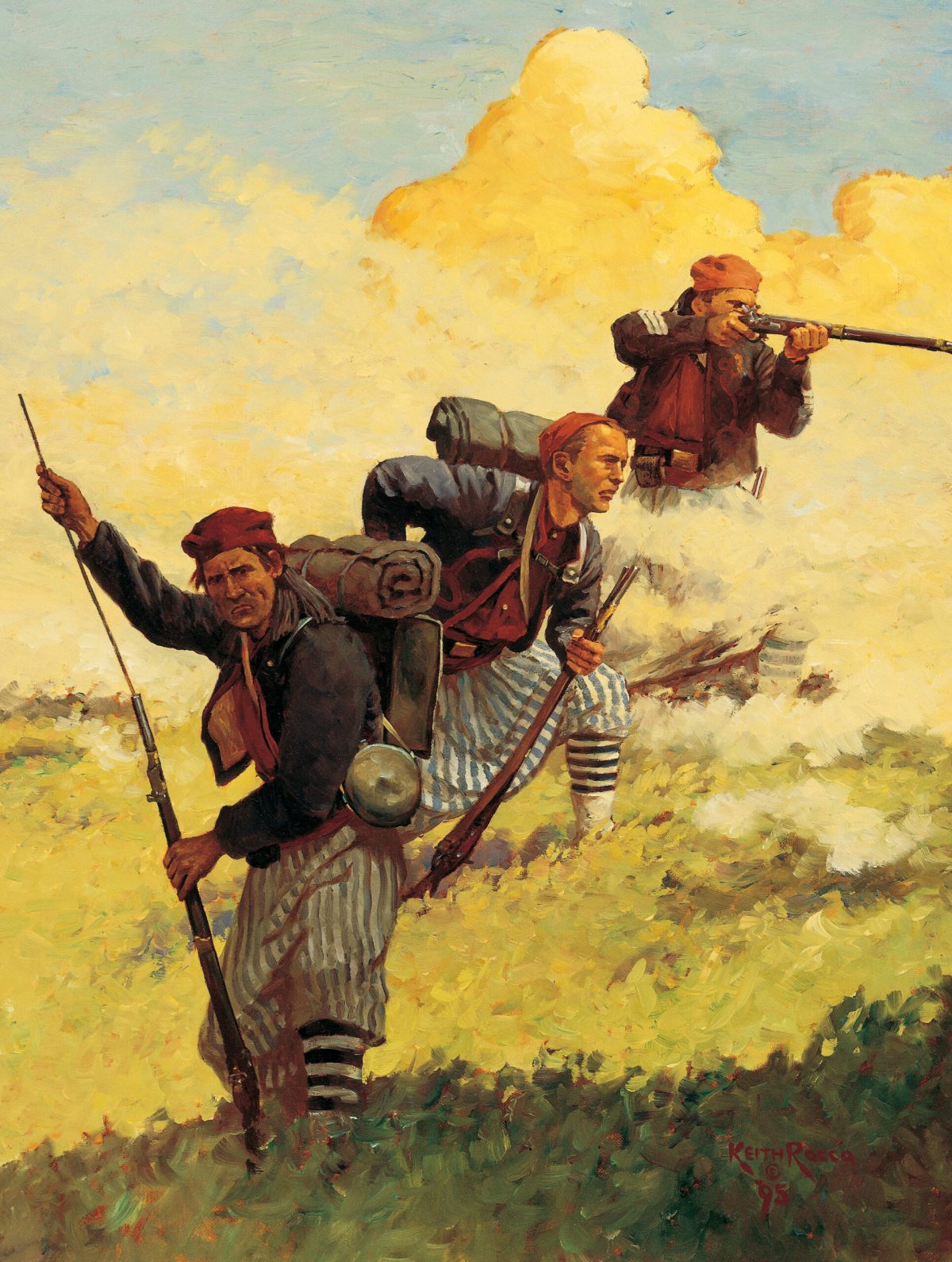

Initially they were all adorned with regular-issue Confederate uniforms, but they did wear distinctive wide-brimmed hats with slogans painted on the bands such as “Lincoln’s Life or a Tiger’s Death” and “Tiger in Search of Abe.” A rich benefactor, Alexander Keene Richards, admired them and purchased one company (the “Tiger Rifles”) wildly colored Zouave-style uniforms consisting of a red fez and shirt, a dark blue jacket trimmed in red, baggy blue-and-white-striped pants, and white gaiters to fit over most of their blue-and-white-striped socks. They were armed with .54-caliber Mississippi rifled muskets and had huge Bowie knives strapped to their waists. Stitched on their flag, ironically, were the words “As Gentle As” adjacent to a resting lamb in the center.

A Virginia native, Chatham Roberdeau Wheat was a veteran of many wars, and during the fighting in Mexico in 1846-48 received particular praise from General Zachary Taylor, who described him as “the best natural soldier he had ever seen.” He followed that up with military forays in Cuba, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Italy.

In addition to being a born leader, Wheat was a physically imposing figure, standing 6-feet-4 and weighing nearly 275 pounds. He demanded respect from the soldiers serving under him and was stout enough to earn it. At one point, Wheat was overheard screaming at his men, “If you don’t get to your places, and behave as soldiers should, I will cut your hands off with this sword!” It was widely acknowledged that his men feared him and that he was the only person able to control them.

Despite his rough exterior, Wheat interacted gentlemanly with the ladies of New Orleans. One Crescent City girl, 16-year-old Clara Solomon, was highly impressed with the major and was a family friend of one of his company commanders, Captain Obed P. Miller. Before the Tigers were scheduled to head off to war on June 15, 1861, Solomon traveled to Camp Moore in a desperate attempt to see “Maj. Wheat’s first special battalion.”

The giddy teen jotted in her journal:

“But hush! we are nearing Tangipahoa [where Camp Moore was situated]! The whistle is sounding! we are at the depot! ‘What hope, what joy our bosom’s swell!!’ Quickly my head is thrust out the window in search of one familiar, well beloved form [Battalion Adjutant Allen C. Dickinson]. The report! It is seen!! A moment more and we are with it. Our fears are ended. They have not gone! But one received the ‘kiss salute.’ How tantalizing!! He [Dickinson] was glad to see us! Sufficient! We slowly wind our way to the Hotel. We remain there a few moments and then proceed to the seat of action, ‘The Camp,’ accompanied by Capt. White and his wife.”

Unexpectedly, the unit’s departure to Virginia was delayed until the following Thursday. The soldiers were eager for a fight and seemed somewhat blue because of the delay. As Solomon would recall, “When we arrived at our quarters, the first object that attracted our attention was our ‘handsome Major [Wheat],’” who, she wrote, “greeted them very cordially.” Lamenting that Wheat was without a female companion, she offered to be his escort for the evening activities and later chided the major for not relaying his “proper” goodbyes to her at night’s end.

Once Wheat and his men finally departed on trains to Virginia, they found themselves packed tightly in the rail cars, much like sardines in a can. The companies comprising the battalion consisted of the Walker Guards (Robert A. Harris, commander); Tiger Rifles (Alexander White); Delta Rangers (Henry C. Gardner); Catahoula Guerrillas (Jonathan W. Buhoup); and Old Dominion Guards (Obed Miller). It was a plodding, uncomfortable ride, but it allowed for overnight stops. Local crowds cheered them on and often convinced the train to stop so they could pass out goodies to the Louisianans. One gift was a big cake made especially for Wheat.

The trip, though, was not entirely pleasant. During a stop at Opelika, Ala., Wheat’s men left the train and seized control of a hotel, including the bar inside. Unable to clear the troublesome men out of the building, the local authorities sought assistance from the major, who at the point was fast asleep on the train. Wakened, Wheat rushed to the scene, pistol drawn, and immediately ordered the belligerents to disperse and return to their railcars. But for a few men, all obeyed the order. Of those continuing to resist, two ruffians were clearly identified as the ringleaders. A witness, Colonel William C. Oates of future Gettysburg fame, later disclosed: “Wheat shot both of them dead. He told me the only way to control his men was to shoot down those who disobeyed or defied him, yet they loved him with the fidelity of dogs.”

Upon the battalion’s arrival in the Old Dominion, the men made an impression on the soldiers of the 18th Virginia Infantry, one of whom recalled witnessing “one freight car…pretty nearly full of Louisiana ‘Tigers’ under arrest for disorderly conduct, drunkenness, etc., most of which were bucked and gag[ged].”

At Lynchburg, former bookstore-clerk-turned-Catahoula Guerrilla Lieutenant William D. Foley wrote: “Our destination is ‘Manassas Gap’. We will have the gratification to participate on the ‘Big Fight’ on Virginia’s soil, the first of Louisiana’s troops. The enemy outnumber us, but we are all prepared, and more than anxious for the Conflict. Troops from Richmond are being sent to the Gap. Tiz a place we must and will hold. The God of battles being with us.”

Before they could reach Manassas, however, the battalion clashed with Federal soldiers at Seneca Dam on the Potomac River.

“Our blood was on fire”

Many of the Tigers were immigrants—a large number from Ireland who had fled that country’s potato famine. As the New Orleans Daily Delta noted, “As for our Irish citizens—whew!—they are ‘spiling’ for a fight.”

It wouldn’t take long for them to get their wish. After McDowell’s forces were rebuffed attempting to cross Bull Run Creek at Blackburn’s Ford on July 18, the Union general was convinced it was too heavily defended and began looking for another point along the Confederate lines to assault. He moved his forces upstream and on the morning of July 21 put his renewed attack plan in place.

Just before daybreak, Southern pickets near the Stone Bridge heard a large movement of troops approaching their position. Colonel Evans deployed one of Wheat’s companies and some of his South Carolinians as skirmishers by the bridge, while the rest of his brigade took position on the nearby hills overlooking the bridge and the Warrenton Turnpike. The Union threat at the Stone Bridge, however, was merely a demonstration. The bulk of McDowell’s force was intending to cross 2½ miles north at Sudley Ford.

Soon, a Confederate signal station in Manassas—manned by future Confederate luminary Edward P. Alexander—alerted Evans that a large Union force was moving to turn his left flank. Evans and Wheat agreed they had to shift their lines to meet this new enemy front, hoping reinforcements would hastily arrive. With no desire to abandon such an important position entirely, the commanders left Lieutenant Adrian and a contingent of Tigers guarding the Stone Bridge.

Confusion among the Louisiana and South Carolina troops proved a problem, as the latter unwittingly fired on their Pelican State comrades while navigating a wooded area, and the Louisianans returned the fire. Wheat rushed to the scene to stop the shooting, but not before two of his men lay mortally wounded.

At about 9:45 a.m., Union Colonel Ambrose Burnside’s men advanced with bayonets fixed through a heavily wooded area into a clearing and found themselves flushing out the Catahoula Guerrillas, then hiding in the tall brush. Relayed Guerrilla Sergeant Robert Richie: “[T]he enemy opened on us, and we had the honor of opening the ball, receiving and returning the first volley that was fired on that day….After pouring a volley, we rushed upon the enemy and forced them back under cover.”

The Guerrillas’ advance at the double-quick forced Burnside’s startled men back into the cover of the forest. The Union colonel, however, had six cannons total, and some were lined up to repulse the Southerners. Guerrilla Drury Gibson remembered the deadly fire, writing, “The balls came as thick as hail [and] grape, bomb and canister would sweep our ranks every minute.”

Some of the Tiger Rifles and Catahoula Guerrillas dropped their Mississippi Rifles, which were bereft of lugs to hold bayonets, and unsheathed their Bowie knives before charging the Federals with ferocity. In later describing the conflict, one Alabama soldier called the Louisianans “the most desperate men on earth,” crowing that when they threw their knives at the enemy, they “scarcely ever [missed] their aim.” Worse for the Yankees, those large knives had strings attached, allowing them to be retrieved after they plunged into an enemy soldier’s body.

Vividly portraying the attack’s desperate moments, Ritchie crowed: “Our blood was on fire. Life was valueless. They boys fired one volley then rushed upon the foe with clubbed rifles beating down their guard; then they closed upon them with their knives. I had been in battles several times before, but such fighting was never done, I do not believe as was done for the next half hour[;] it did not seem as though men were fighting, it was devils mingling in the conflict, cursing, yelling, cutting, shrieking.”

One Tiger’s account of the battle found its way into a Richmond newspaper:

“As we were crossing a field in an exposed situation, we were fired upon (through mistake) by a body of South Carolinians, and at once the enemy let loose as if all hell had been left loose. Flat upon our faces we received their shower of balls; a moment’s pause, and we rose, closed in upon them with a fierce yell, clubbing our rifles and using our long knives. This hand-to-hand fight lasted until fresh reinforcements drove us back beyond our original position, we carrying our wounded with us. Major Wheat was here shot from his horse; Captain White’s horse was shot under him, our First Lieutenant [Thomas Adrian] was wounded in the thigh, Dick Hawkins shot through the breast and wrist, and any number of killed and wounded were strewn about.

“The New York Fire Zouaves, seeing our momentary confusion, gave three cheers and started for us, but it was the last shout that most of them ever gave. We covered the ground with their dead and dying, and had driven them beyond their first position, when just then we heard three cheers for the Tigers and Louisiana. The struggle was decided. The gallant Seventh [Louisiana Infantry] had ‘double quicked’ it for nine miles, and came rushing into the fight. They fired as they came within point blank range, and charged with fixed bayonets. The enemy broke and fled panic-stricken, with our men in full pursuit.

“When the fight and pursuit were over, we were drawn up in line and received the thanks of Gen. Johnston for what he termed our ‘extraordinary and desperate stand.’ Gen. Beauregard sent word to Major Wheat, ‘you, and your battalion, for this day’s work, shall never be forgotten, whether you live or die.’”

The Shreveport Daily News described the battalion as “a specimen of the toughest and most ferocious set of men on earth,” and an account that ran in the Wilmington [N.C.] Journal provided input by Tiger Lieutenant Allen C. Dickinson, who had been shot in the thigh by a Minié ball. “[O]ut of 400 which constituted that command, there were not more than 100 that escaped death and wounds. Maj. Wheat was shot through the body, and was surviving on Wednesday, although his case is exceedingly critical.” According to Dickinson, Captain Buhoup and his Guerrillas “fought with desperation.”

Dickinson, a Virginia native who had been living in New Orleans for several years, had been the one to draw Clara Solomon’s interest back at Camp Moore. When news of the battle reached New Orleans, she lamented, “No news about our Lieut. Dickinson.” Informed of Wheat’s fate, she wrote: “Just think the two persons, for whom we care most in the war, we should hear, in the very first battle, of one being seriously wounded, and nothing of the other.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

A contributor to the Richmond Dispatch, writing under the pseudonym “Louisiana,” tried to clear things up, including the status of the battalion’s leader. “The gallant Colonel Wheat is not dead,” he wrote. “I have just got[ten] a letter from Capt. Geo. McCausland, Aid[e] to Gen. Evans, written on behalf of Major Wheat, to a relative of Allen C. Dickinson, Adjutant of Wheat’s Battalion.”

The contributor went on to describe Dickinson’s injury in detail: “The wound is in his leg, and although not dangerous….His horse having been killed under him, he was on foot with sword in one hand and revolver in the other, about fifty yards from the enemy, when a Minie ball struck him. He fell and lay over an hour, when fortunately, Gen. Beauregard and staff, and Capt. McCausland, passed. The generous McCausland dismounted and placed Dickinson on his horse. Lieut. D. is doing well and is enjoying the kind care and hospitality of Mr. Waggoner and family, on Clay Street, in this city.”

The Shreveport Weekly News published the lyrics of a song written expressly about the battalion’s exploits. Borrowing its tune from the song, “Wait for the Wagons,” it had three stanzas praising the Louisianans at First Manassas—the song’s title aptly changed to “Abe’s Wagons.”

We met them at Manassas, all formed in bold array,

And the battle was not ended when they all ran away.

Some left their guns and knapsack, in their legs they did confide,

We overhauled Scott’s carriage, and his epaulets besides.

[Chorus]

Louisiana’s Tiger Rifles, they rushed in for their lines,

And the way they slayed the Yankees, with their long Bowie knives.

They laid there by the hundreds, as it next day did appear,

With a countenance quite open, that gaped from ear to ear.

[Chorus]

The battle being ended, and Patterson sent back,

Because he did not fight us, for courage he did lack.

Abe Lincoln he got so very mad, when his army took a slide,

And we jumped into his wagons, and we all took a ride.

A British reporter recalled a peculiar tactic practiced by the Louisianans, writing, “[T]hey would maintain a death-like silence until the foe was not more than 50 paces off; then delivering a withering volley, they would dash forward with unearthly yells and [when] they drew their knives and rushed to close quarters, the Yankees screamed with horror.”

Lieutenant Adrian rejoined the battalion with his scant force, and after being wounded in the thigh fell to the ground. When he noticed some of the Tigers falling back, he propped himself up on one elbow and shouted at the top of his lungs, “Tigers, go in once more. Go in my sons, I’ll be great gloriously God damned if the sons of bitches can ever whip the Tigers!”

First-person reports were published in New Orleans’ Daily True Delta after the unnamed “vivandier of the Tiger Rifles” strode into their offices with letters from some Tigers to their friends back home. The newspaper cited:

“These letters give a detailed history of the Tigers’ sayings and doings since their departure hence, and especially their participation in the battles of…Manassas. The loss among them, we are pleased to say, is much less than has been reported. They have twenty-six of their seventy-six, wholly uninjured, and several more who are but slightly wounded. That they fought like real tigers everybody admits and Gen. Johnston, it is said, complimented them especially on the brave and desperate daring which they had exhibited.

“[Lieutenant] Ned Hewitt reported here as having been killed, did not receive the slightest wound. Moreover, none of the officers of the Company were killed. Two of the Tigers who had been missing for several days after the fight, made their way to Manassas on Thursday last, one being slightly and other pretty badly wounded. The kindness of the Virginia ladies to the wounded soldiers is said to be beyond all praise—like that of a mother to a child or a wife to a husband. Soldiers so nursed and attended can never be anything else than heroes and conquerors.”

Having defied death—and skeptical doctors—when gravely wounded at First Manassas, Wheat would not be so lucky when shot in the head 11 months later at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, the third of the Seven Days’ Battles on June 27, 1862. His purported final words—“Bury me on the field, boys!”—were to open a poem in his honor. Wheat had been the only one to truly rein in the rambunctious battalion, which formally disbanded on August 15, 1862. Fortunately, their legend survives.

A frequent contributor, Richard H. Holloway is a member of America’s Civil War’s editorial advisory board. He thanks Glen Cangelosi for his help in preparing this article.