The American commander was pressured to hang a Redcoat officer in retaliation for a patriot’s murder

The conflict that rent the United States 1861-65 was not America’s first civil war—the American Revolution was. The fight for independence pitted neighbor against neighbor and family member against family member, exemplified by the split between Founding Father Benjamin Franklin and Tory son William, the final royal governor of New Jersey. Violence arising from these and countless other personal breaks rendered expanses of the former colonies “danger land,” as one historian has called the impact of the internecine warfare that raged between loyalists and patriots.

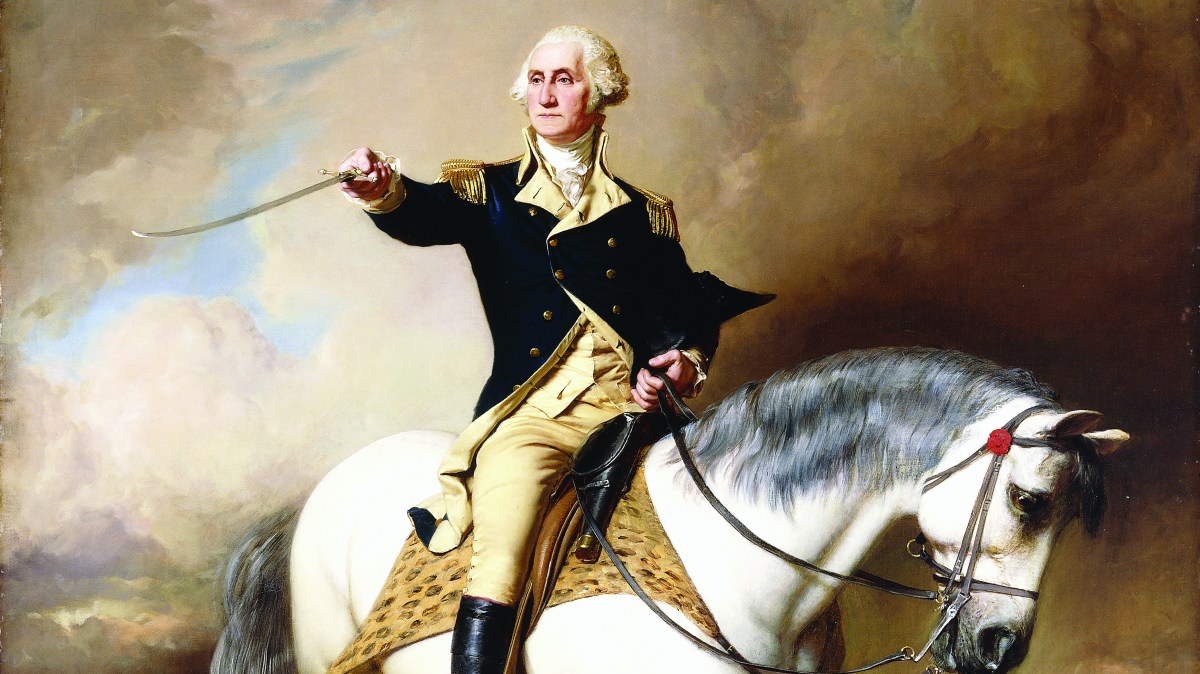

In one instance, Continental Army commander George Washington, seeking to control a fractious military and political situation in the aftermath of the surrender at Yorktown, attempted to answer an act of loyalist outlawry. Washington undertook a tenuously logical reprisal that in satisfying rebel militia anger stood to besmirch his own reputation and vastly complicate reunification of former colonists at odds over the rebellion. That neither eventuality occurred testifies to the practicality of which Washington was capable, even in very personal circumstances.

The phrase “danger land” certainly defined northern New Jersey in 1782. Following patriot victories at Trenton and at Princeton in 1776-77, militia in New Jersey had driven hundreds of loyalists, including the younger Franklin, to flee into British-held New York. Once Refugees—as loyalists called themselves—had Crown protection, some returned to avenge themselves on those who had dispossessed them. In 1780, upon forming a Board of Associated Loyalists headed by William Franklin, King George III created a Refugee army under the Board’s control.

Refugee militia attacks on New Jersey patriot towns intensified, at times degenerating into vendetta. Both camps repeated stories of rape, mutilation, and murder that, accurate or not, inflamed deeply embittered animosities. These emotions and the violence they engendered persisted long after October 1781, when British forces surrendered at Yorktown. The terms of that capitulation, while not ending the war, guaranteed that the hundreds of British officers yielding at Yorktown to American and French forces were safe from reprisal or retaliation.

But reprisal and retaliation had become a steady diet for both loyalists and patriots. For example, in 1780 a band of Associated Loyalists that included one Philip White attacked the Monmouth County, New Jersey, residence of patriot John Russell. Raiders burned Russell’s home, wounded him, killed his father, and slipped back to New York. Two years later, in late March 1782, Philip White left New York for Monmouth to visit his wife or to undertake another raid—accounts vary. Patriot militiamen, including John Russell, caught him. Within hours, White was dead, his mutilated corpse shoveled into a makeshift grave. However, that militia’s commander, Captain Joshua Huddy, did not participate in that action. Earlier that month, the highly regarded Huddy had been trying to protect a blockhouse at the little town of Dover, today known as Toms River, when he was taken prisoner. At the time of White’s death, Huddy was in British military custody in New York.

Deciding to avenge Philip White’s murder, the Board of Associated Loyalists gulled British commander-in-chief Sir Henry Clinton into believing that the rebel Huddy was to be exchanged for a captive Associated Loyalist. On April 2, 1782, loyalists led by Captain Richard Lippencott—Philip White’s brother-in-law—took custody of Huddy at Sandy Hook, New Jersey. Lippencott and company promptly lynched the militiaman, leaving Huddy’s corpse to dangle overnight plastered with placards, one reading, “Up went Huddy for Philip White.”

Huddy’s men retrieved his remains, laid them in state at Monmouth Courthouse, and swore vengeance, declaring that if General Washington did not respond to the slaying with a reprisal, they would bring about “a scene at which humanity itself may shudder.” The ultimatum put Washington, stationed at Newburgh, New York, in a fix. Under normal conditions, he was not one for retaliation, but these were not normal conditions. Washington took Monmouth’s dare, calling Huddy’s death “the most wanton, unprecedented and inhuman Murder that ever disgraced the Arms of a civilized people.”

Before his officers could discuss the lynching, Washington individually polled them, seeking each man’s written opinion on the matter. Reactions were nearly unanimous: retaliation, one officer wrote, was “justifiable and expedient,” not only to discourage loyalist atrocities but to keep New Jersey patriots from taking the law into their own hands. Washington’s officers agreed that the victim selected to die in retaliation should be of Huddy’s rank—captain—and should have surrendered at his own discretion and not under terms of convention or capitulation that guaranteed exemption from reprisal.

Washington notified the Continental Congress of his decision to retaliate for Huddy. Early in May he learned by letter that members unanimously approved his proposal.

Delegates were, they said, “deeply impressed with the necessity of convincing the enemies of the United States … that the repetition of their unprecedented and inhuman cruelties … will no longer be suffered with impunity.” They offered “their firmest support.”

On April 21, 1782, Washington wrote to Clinton, curtly demanding that the British army deliver self-appointed hangman Lippencott into American hands. “To save the innocent, I demand the guilty,” Washington wrote. “In Failure of it, I shall hold myself justifiable in the Eyes of God and Man, for the measure to which I shall resort.”

Washington’s sharp words stung Clinton. “I cannot conceal my surprise and displeasure at the very improper language you have made use of,” Clinton replied. He declared himself “greatly surprised and shocked” at the news of Huddy’s death, which had come to him only four days before he received Washington’s letter. Clinton already had ordered a “strict enquiry” into the case, he told his counterpart. Based on the results of that inquiry, which was under way, Clinton wrote, the perpetrators would be brought to trial. However, he added, no matter what his staff learned about the Huddy case he had no intention of giving Lippencott or anyone else into Washington’s charge. “Violators of the Laws of War” are best “punished by the Generals under whose Powers they act,” the British general wrote.

If the British refused to hand over Lippencott, Washington concluded, he was “under the disagreeable necessity of retaliating, as the only means left to put a stop to such inhuman proceedings.” The sacrificial captain was to be chosen from among peers. Washington assigned General Moses Hazen to find a cadre of POW captains who had surrendered on their own, Hazen’s search for a proper target of reprisal foundered. Inexplicably, when he could not find unconditional prisoners of war, Washington decided to make the fatal selection from a group of 13 British captains who had surrendered with Cornwallis at Yorktown in October 1781 and were being held near Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Under the terms of their surrender, they were guaranteed haven from reprisal.

“It was much my Wish to have taken for the purpose of Retaliation, an Officer who was an unconditional prisoner of War—I am just informed by the Secty at War, that no one of that Description is in our power,” Washington wrote Hazen. “I am therefore under the disagreeable necessity to Direct that you immediately select, in the Manner before presented, from among all the British Captains who are prisoners either under Capitulation or Convention One, who is to be sent on as soon as possible, under the Regulations & Restrictions contained in my former Instructions to you.” This directive to Hazen calls into question Washington’s grasp of the surrender agreement with Cornwallis. Article 14 of the capitulation terms protected those surrendering against retaliation or reprisal. Was His Excellency unaware or forgetful of the terms, or was he ignoring them? For a man regarded as having astute judgment, Washington was making one of his poorest decisions ever.

The mechanism for choosing the sacrificial victim was a macabre lottery. On Monday May 27, 1782, with the 13 captains and other British POWs present at the Black Bear Inn in Lancaster, two sets of paper slips were put into separate baskets. Slips in the first basket bore the names of the 13 captains. The second basket also held 13 slips—12 blank, one bearing the chilling message “unfortunate.” A drummer boy drew a slip from the first basket, called the name, and then took a slip from the second basket. Ten times he called names and ten times he drew blanks. The 11th name called was that of Captain Charles Asgill, 19. A soldier with the First British Regiment of Foot since enlisting at 16 against his father’s wishes, Asgill was his parents’ only son. His pro-American father, also Charles, had been lord mayor of London. Mother Sarah Theresa, Lady Asgill, was of a wealthy Huguenot émigré family. The drummer boy now reached into the second basket. The slip he selected read “unfortunate.” The sight of his fate nearly unmanned Asgill. His commanding officer, Major James Gordon, steadied him, saying, “For God’s sake, don’t disgrace your colors.”

Gordon accompanied Asgill to confinement at Monmouth, New Jersey, where execution awaited, and remained as a companion through the younger man’s captivity. Among Asgill’s tasks was composing a letter to his ill father, asking forgiveness for joining the army. Asgill expected that by the time his father read his letter he would be dead. His jailers took delight in reminding him that a gibbet had been built in Monmouth and a sign attached to it reading, “Up Goes Asgill for Huddy.”

General Washington felt empathy for the young soldier, but also wanted to make sure he was held securely, which at first appeared not to be the case. “I am informed that Capt. Asgill is at Chatham, without Guard, & under no constraint,” the General wrote in orders to the troops at Monmouth. “This if true is certainly wrong—

I wish to have the young Gentleman treated with all the Tenderness possible, consistent with his present Situation—But until his Fate is determined, he must be considered as a close prisoner & be kept in the greatest Security.”

Washington’s retaliatory gesture outraged the British, who immediately upon learning of Huddy’s murder had condemned it. “Washington had determined to revenge upon some innocent man the guilt of a set of lawless banditti,” a Briton said. Some Americans agreed. Alexander Hamilton, who had resigned from the army after Yorktown and at the moment on the outs with Washington, forcefully critiqued the situation to General Henry Knox, an intimate of the commander-in-chief. Hamilton had sternly opposed the “rigid justice” of Washington’s decision to execute Major John André on October 2, 1780, for espionage in the Benedict Arnold treason plot, although Hamilton recognized that André had to die. The Asgill affair was of a different nature, Hamilton explained to Knox. “A sacrifice of this sort is entirely repugnant to the genius of the age we live in and is without example in modern history nor can it fail to be considered in Europe as wanton and unnecessary,” Hamilton said. “If we wreak our resentment on an innocent person, it will be suspected that we are too fond of executions. I am persuaded it will have an influence peculiarly unfavorable to the General’s character.”

Washington, never known for backing down, clutched hard at his decision. “My Resolutions have been grounded on so mature Deliberation, that they must remain unalterably fixed,” he said. “The Enemy ought to have learnt before this that my Resolutions are not to be trifled with.” Invoking the backing he had received from Congress and his officers, he said his position “cannot be receded from; Justice to the Army & the Public, my own honor, & I think I may venture to say, universal benevolence, require them to be carried into full execution.”

Washington’s claim that “universal benevolence” demanded he execute an officer protected under a surrender agreement clearly shows how far he was willing to contort logic to avoid losing face. Hamilton argued for “inconsistency” over “consistency,” but although Washington was hoping in some way to avoid executing Asgill, he had convinced himself that he could not retreat publicly. He was trapped by an inability to backtrack.

In August a British court martial exonerated Lippencott, accepting his counsel’s hoary argument that he merely had been a soldier following orders—in this case, from the Board of Directors of Associated Loyalists. Given that ruling, British revulsion at Huddy’s murder, and the fact that their leadership had disbanded the Board of Directors of Associated Loyalists while promising further investigation, Washington bumped Asgill’s fate to Congress. The case, the General declared, had become “a great national concern, upon which an individual ought not to decide.” He requested that Congress “chalk a line for me to walk.”

If Captain Asgill was to die, it would be on Congress, not on George Washington.

The matter indeed was expanding beyond “a great national concern” into an international cause célèbre, thanks in part to Lady Asgill and the headlines she was making on the Continent with her pleading for her son’s life. “The public prints all over Europe resounded with the unhappy catastrophe,” the Baron von Grimm recorded in his memoirs. The topic “interested every feeling mind … and the first question asked of all vessels that arrived from any port in North America, was always an inquiry into the fate of that young man, ‘Does Asgill still live?’”

Lady Asgill made an ally of French foreign minister Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, with a single powerful letter. “My son, my only son, dear to me as he is brave, amiable as he is beloved, only nineteen years of age, a prisoner of war, in consequence of the capitulation of Yorktown, is at present confined in America as an object of reprisal,” she wrote. “Let your sensibility, sir, paint to you my profound, my inexpressible misery, and plead in my favor; a word, a word from you, like a voice from Heaven, would liberate us from desolation, from the last degree of misfortune. I know how far General Washington reveres your character. Tell him only that you wish my son restored to liberty, and he will restore him to his desponding family; he will restore him to happiness. The virtue and courage of my son will justify this act of clemency.”

Vergennes, who had the ear of King Louis XVI, took up the cause. France had reasons other than his mother’s peace of mind to tilt Asgill’s way. Insofar as that nation was a signatory to the surrender Washington had accepted, the young captain was France’s prisoner as well as America’s. In a related effort to save Asgill, French General Jean Baptiste Donatien de Viemur, Comte de Rochambeau, unburdened himself to Chevalier de la Lazerne, France’s minister to the United States, in a letter Rochambeau instructed the minister to share with but not give to Washington lest the document land in the official record. In his communique, Rochambeau explained that he was sure Washington would not want to soil Cornwallis’s honorable capitulation by a deed of reprisal that the Americans had absolutely no right to commit, and which Europeans would regard as a barbarous injustice. Rochambeau said later that Washington, while unwilling to recant publicly, assured him in private that Asgill would not perish by his order. That exchange may have figured in Washington’s decision to now extend a very generous parole to Captain Asgill and Major Gordon, allowing them proximity to the British lines in New York. Perhaps Washington was hoping Asgill would escape and solve both their dilemmas. If so, he was disappointed.

Vergennes sent Lady Asgill’s letter to Washington, along with a letter of his own stating that King Louis and Queen Marie Antoinette would be very grateful if the general could see his way to mercy. Washington, perceiving a solution, immediately sent a courier to Congress carrying Lady Asgill’s letter. Finally debating the matter, Congress had decided to call the question the morning of October 30, 1782. Members were expecting to vote to execute Asgill. Before that vote could be taken, however, Washington’s courier arrived, upending expectations. Upon reviewing the Asgill letter and one from Vergennes, Congress voted unanimously that Asgill’s life “should be given as a compliment to the King of France,” ordering the young captain freed and sent home. “We got clear of shedding innocent blood by a wonderful interposition of Providence,” Elias Boudinot, representative from New Jersey and later president of the Continental Congress, wrote in his journal. Washington happily wrote Asgill with the good news. The captain decamped for home, paying a crew to row him to the departing British ship Shallow, whose call to board before casting off from a New York wharf he narrowly had missed.

Within a few years, word began to come from London that Asgill was complaining about the “peculiar hardships” he had endured for six months in a New Jersey prison. Tench Tilghman Sr., whose son had been an aide to Washington, told the general in 1786 that among other allegations Asgill apparently was telling people his captors had erected a gibbet outside his prison window as a taunt, that Washington countenanced such abusive behavior, and that only Rochambeau’s intervention had saved his life.

George Washington was notoriously thin-skinned, especially on matters involving personal honor. The general angrily responded that Asgill’s statements were baseless calumnies. He described in considerable detail a generous parole he had extended Asgill and Gordon, forgetting that earlier he had tightly limited Asgill’s movements. Calling his former captive “defecting in politeness,” he observed that Asgill, upon being repatriated, had lacked the grace to write and thank him.

Washington ordered aides to publish his letters regarding the affair. The New Haven Gazette and Connecticut Magazine carried the correspondence in their editions of November 1786. In December, Asgill, reading the American newspapers, composed and sent an angry retort that went unpublished. No gibbet was placed outside his cell, he acknowledged in his letter, but he heard often about those Monmouth gallows labeled “Up Goes Asgill for Huddy.” It had deeply distressed him during his captivity to be denied delivery of mail from his family, a hurt he traced directly to George Washington. As for not thanking Washington for not hanging him, Asgill wrote, “My judgement told me I could not with sincerity return thanks [which] my feelings would not allow me to give vent to.

Following his release, Captain Asgill rose to the rank of general. Serving in Ireland during the Rebellion of 1798, he was to oversee the execution of a rebel named William Farrell. However, his wife, Lady Sophia Asgill, argued that since Queen Marie Antoinette’s petition to General George Washington had saved Asgill’s life, he was duty bound to do the same at her request. He did as she asked. Asgill was 60 when he died in 1823, 40 years after his near-execution.

Captain Joshua Huddy’s brutal lynching strenuously taxed George Washington’s logic and ethics. Public opinion on the slaying overwhelmingly favored a tough response. Had Washington not threatened retaliation, he might not have been able to retrieve the situation. He maintained control by committing to a dangerous course from which his personality would not allow him to deviate. Needing a sacrificial victim, he somehow justified executing a convention prisoner even as he agonized over that path. Moved to seek a way out, he bought time, consulted Congress, and gratefully took the escape Vergennes proffered, avoiding a self-inflicted and permanent stain on his reputation.

This story appeared in the February 2020 issue of American History.