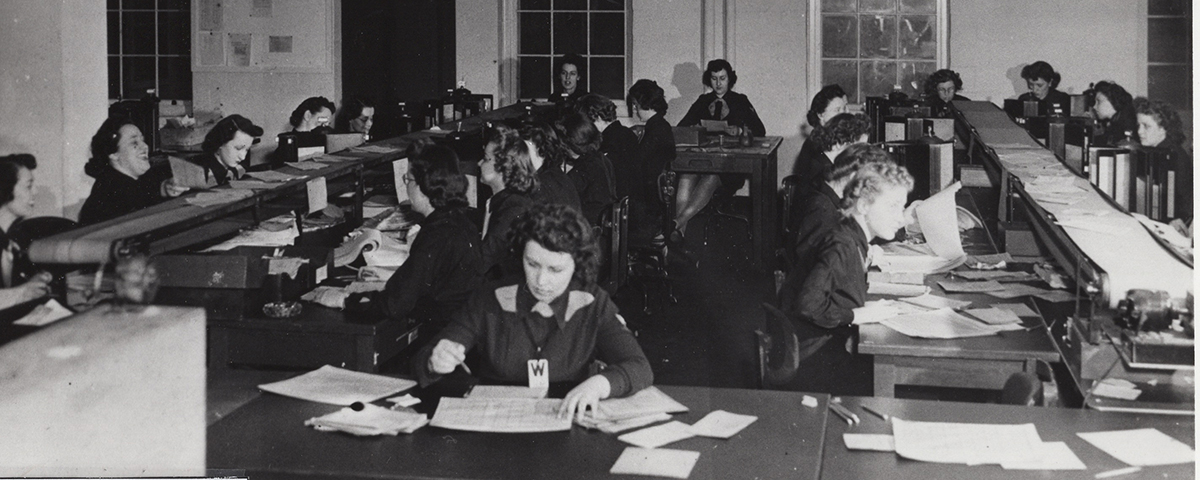

America counted on bright young women to break Axis codes

DURING WORLD WAR II, the American armed services recruited more than 10,000 women to do what pioneering code breaker Elizebeth Friedman (see p. 16) did and more. Like Friedman’s, their story was suppressed (See related online interview, “Elizebeth Friedman: Hidden Heroine”)

In Code Girls, Liza Mundy introduces the smart, lively, very human women whose exploits stayed secret too long. Officialdom needed these cryptanalysts to free men for combat, but also saw

(Bettmann/Getty)

them as suited to tasks initially deemed menial. “It was generally believed that women were good at doing tedious work—and I discovered early on, the initial stages of cryptanalysis were very tedious, indeed,” recalled Ann Caracristi, who went on to a distinguished career at the National Security Agency.

Code girls had to be intelligent and roundly educated. Some came from the Seven Sisters colleges—the class-conscious Navy wanted only the best, the brightest, and the oh-so-social. The Army sent handsome recruiters to state colleges and in 1943 began seeking female schoolteachers for the work.

The Navy commissioned most of its collegiate code breakers. These WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service) occupied the campus of Mount Vernon Junior College in northwest Washington, DC, renamed the Naval Annex. As the Army code breaking unit outgrew offices in Washington, DC, its women moved to nearby Arlington, Virginia, living and working at a commandeered women’s junior college, Arlington Hall. Unlike the Navy, the Army had little interest in commissioning code girls. Often a male Army officer answered to a female civilian. Mundy writes delightfully of the outfits’ rivalry, with Army civilians grumbling about careerist WAVES and the Navy harping on Arlington Hall’s less military mien—rowdiness and men.

Army code girl Wilma Berryman broke Japanese Army administrative codes communicating details about troop strength, ration allotments, and transportation,

By Liza Mundy

Hachette Books, 2017

$28

extrapolating from those data to set up American submariners to torpedo enemy transports. Navy code girls pieced together Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s inspection itinerary. American fighter pilots downed his plane, vengeance for Yamamoto’s hand in planning Pearl Harbor.

The Navy assigned enlisted WAVES to a top-secret Dayton, Ohio, facility where the women meticulously constructed electromagnetic machines that turbocharged

the American version of the German Enigma enciphering device. By 1944, analyzing Enigma messages and others from Japanese diplomats in Europe, code girls isolated key intelligence about Germany’s Atlantic Wall, helping D-Day along.

After V-J Day, the services told the women that as patriots, they should go home and keep their lips zipped or face perdition. A few had the clout to stay on and fight the Cold War. Caracristi in 1980 was named the first female deputy director of the National Security Agency.

Most code girls married, raised families, and took their wartime secrets to their graves, unaware that NSA had declassified their work in 1995. In a race with mortality, Mundy was interviewing surviving former code breakers as late as 2017. Their stories often astonished these heroines’ families.

—Nancy Tappan is senior editor of American History