We’ve been willing to sue. We’ve gone to court on a lot of things.

Airman John Rowan flew in planes over North Vietnam with a team listening in on the enemy’s communications and translating them into English to guide or warn American pilots.

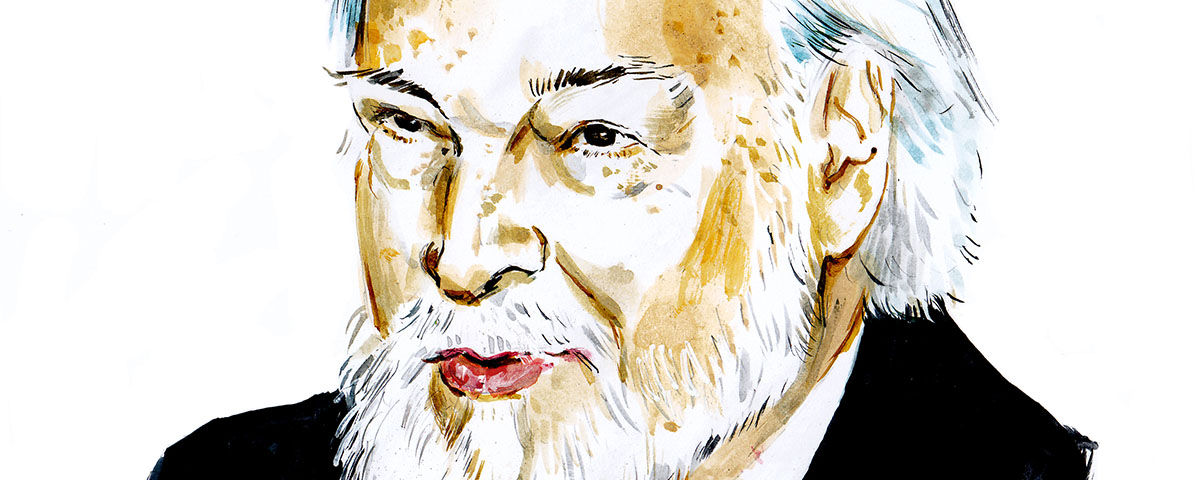

Today, as president of Vietnam Veterans of America, he is listening to his fellow veterans and making sure policymakers understand what they are saying.

Rowan began working on behalf of veterans almost immediately after returning to the States, while also building a career in public service with various government organizations in New York City. He was an investigator in Comptroller’s Office when he retired in 2002.

Rowan has been with the VVA since it was founded in 1978 as the Council of Vietnam Veterans (the name changed in 1979). He helped start the Queens chapter in 1981 and served as president of the New York State Council from 1995 to 2005, when he became the national president. At the VVA convention in August 2017, Rowan was elected to his seventh two-year term as head of the 83,000-member organization, based in the Washington suburb Silver Spring, Maryland.

In an interview with Editor Chuck Springston, Rowan talked about the VVA’s beginning, achievements and likely future.

Why did you decide to join the Air Force? I joined the Air Force, frankly, to avoid the draft. It was 1965, and I was 19. I had dropped out of Baruch College after one horrible semester. I had gone to a very good high school, Brooklyn Tech, so I went to work as a technician for AT&T. A buddy of mine had gone to the Air Force’s electronics school. And so I figured I would get into that. I took the Air Force qualifying tests and aced them.

After basic training, they said, “How’d you like to take a test in languages?” I said, “Yeah, sure.” I took this language aptitude test and went to school for the Indonesian language in California at the Defense Language Institute in Monterrey for 10 months. After I finished the Indonesian language, they said, “Who would like to cross-train in Vietnamese?” I volunteered and was sent to D.C. to study Vietnamese.

You joined the Air Force to avoid the draft and Vietnam. Then someone said, “Do you want to learn Vietnamese?” Wasn’t that a clue? [Laughs.] Yes, but I wasn’t going to be out in the field. I wasn’t toting a gun, and I thought I was really safe.

I was shipped to Japan in April 1967 at Yakota Air Base outside of Tokyo. Since my Vietnamese wasn’t very good, I was trained on an air-to-ground crypto communications machine, which was a glorified typewriter. I was in the 6988th Security Squadron and trained on the RC-130 while flying off the Russian coastline.

They were shifting crews back and forth from Japan to Da Nang for 30-day TDY [temporary duty] rotations. We were flying missions on RC-130s out of Da Nang off the coast of North Vietnam. We were doing voice intercepts of the pilots/ground controllers, monitoring any air traffic that came off the ground, as well as communication between the commanders and operators of the SAM [surface-to-air missile] sites. My job was to communicate any vital information through the ground site to those units that needed the information.

Were you ever in a plane that was fired upon? No, but in July of ’67, they rocketed the hell of out of us while I was in Da Nang. I spent the night in a bunker. The explosive power was pretty strong, especially when the planes [on the ground] blew up. When I got out in the morning, there was a jet engine sitting in front of the bunker. There was a rear stabilizer of an F-4 stuck in the side of the laundry building, looked like somebody threw it like a tomahawk. They killed about four to five guys that night, could be more, including two guys in my unit who were in wooden barracks.

After they brought us back up to Japan, a whole new squadron was created, the 6990th Security Squadron, which was based on Kadena Air Base in Okinawa. We flew brand new RC-135 jets on 18-hour missions off the coast of North Vietnam. We could hear everything the [North Vietnamese] air traffic controller said to the pilots and whatever they said back. SAM sites have a radar location, a command post and the actual missile, so there’s three locations that are talking to each other all the time. We were intercepting their communications and knew when they were locking on to our pilots. We could warn them. We could also help them identify where the SAMS were so they could try to take them out.

When I was based in Okinawa, I would fly occasionally, but became a squadron clerk because I wanted to go back to school. I figured I would take some courses while I was there. Then my father got lung cancer, so they said, “Go home, kid,” as I was an only child with a job waiting for me. I got out in December of ’67.

You became involved in veterans issues almost immediately after you got home. Why? I went to school at Queens College in the fall of ’68 and was one of the first Vietnam veterans to show up on campus. The head of the political science department was a retired colonel who had taught in the war college and was an expert on Southeast Asia. He was really against the war, not so much ideologically, but he thought the war was being run horribly, that nobody really understood the Vietnamese. He kept feeding me a million books. I read a lot of stuff.

I got involved with Vietnam Veterans Against the War in 1970, but then that got silly really fast.

How so? You had a lot of people who wanted to get us out of the war for a lot of reasons. You had the Marxists who didn’t know what the hell they were talking about, the Leninists and every other freaking-ist. And you had the FBI trying to infiltrate us. But a lot of us weren’t ideologically pro-North Vietnam or any of that crap. We just thought the war was being run very poorly. The Vietnamese weren’t picking up the slack they needed to under the Nixon plan. Vietnamization was a farce. A lot of us were just saying get the hell out of there. Our guys are getting killed for no reason.

But you did have the ideologues, and the crazies ran away with it. A lot of us moved on, got into the VVA. In ’72, I went to work for [Democratic presidential candidate George] McGovern, which was a fiasco.

Fifty years later, how is Vietnam Veterans Against the War seen today? A lot of my guys look at it as left wing and communist. But there was no other Vietnam veterans group out there. The American Legion and the VFW didn’t want us. They were older vets. The guys from World War II didn’t talk about mental health. When Agent Orange [the poisonous herbicide sprayed to kill foliage that hid enemy troops] came up, a lot of them said, “What are you bringing that up for?”

The shrinks who studied the mental health issues were VVAW guys who came up with the term PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. Before that it was Post-Vietnam syndrome. We were the first ones that talked about drugs.

How did the Vietnam Veterans Association get started? It started in 1978 as the Council of Vietnam Veterans, a lobbying group for all these issues that were cropping up—PTSD, Agent Orange, a crappy GI bill [less generous than the one for World War II vets], and the bad treatment the Vietnam vets were receiving. It was founded by Bobby Muller, a Marine officer, who got shot in Vietnam and is a paraplegic. Bobby came out of the VVAW.

We had our first convention in 1983. You had a bunch of Vietnam vets from all walks of life, from cowboys out West to city kids. All kinds of backgrounds, all kinds of service, shoved in a room creating an organization out of whole cloth.

During those years what veterans’ issues did you personally work on? In New York in the late ’70s I was on the board of directors of a program called the Veterans Upgrade Center. We got federal money to help guys who had “bad paper”— generally less-than honorable discharges. There were half a million bad paper discharges issued during the Vietnam era, most of them administratively, for non-court-martial offenses. If you got court-martialed, the odds are you deserved it. You shot somebody or whatever.

But kids were getting bounced out for drug use, AWOL, other stupidity. A lot of them were guys who should have never been in the military in the first place. They [military officials] said, “Sign here and go home.” You’re some 19-year-old, and you don’t care. “Get me out of here.” Now you’ve got an albatross around your neck. You can’t get a job, benefits. You’re screwed for the rest of your life. That’s what we tackled with this discharge upgrade program in New York. We were able to write briefs that would win 70 to 75 percent of our cases [taken to military discharge review boards].

What are the major services that VVA provides today? The biggest is lobbying. Our government affairs operation is the biggest thing we do.

What are your legislative priorities? A bill passed in 2016 called the Toxic Exposure Research Act, which we fought for, and now we’re fighting to get it funded to study the effects of toxic exposure from Vietnam to the present day on the children of veterans. We’ve been holding town hall meetings all around the country, and we believe that a lot of veterans’ children have been affected. Unfortunately, the long list of illnesses is hard to boil down, and nobody’s done any research.

We also fought very strongly for the new GI Bill [signed in August 2017]. We still have lots of issues with Agent Orange. We fought to get more diseases added to the presumptive list [of illnesses the Veterans Affairs Department assumes are related to Agent Orange exposure and thus entitled to disability compensation].

Are you involved in the search for the missing U.S. service members? For 23 years we’ve been going to the Vietnamese with information we have acquired from our members about their dead. A guy killed someone and took stuff home as a souvenir. Forty years later they don’t want it. They give it to us. We try to figure out what it was and bring it back to the Vietnamese by way of our relationships with, interestingly enough, the Vietnamese Veterans Association. Or we give them information on mass grave sites, resulting from large firefights.

Because of our efforts we’ve been on TV over there and in newspapers. We’ve developed goodwill. We’ve literally had someone say, “The guy [American pilot] landed in my backyard.” Now the DPAA [Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency] can go out and do the dig.

Looking back 50 years what do you think is the legacy of the Vietnam War in American history? There’s some bad legacies obviously, with Agent Orange and all of that, but there’s also a much better understanding of PTSD, which doesn’t affect just vets. Lots of people who go through hurricanes and floods are going to have PTSD. So hopefully the country has learned something about mental health issues that will help us out.

What do you think are the lessons of the Vietnam War? Learn what the hell what’s going on before you go somewhere. We didn’t understand Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh was an avid communist, no ifs, ands or buts, but so was [Yugoslavia’s Marshal Josip Broz] Tito, and we cut a deal with him to use him as a kind of a buffer [against Soviet expansion] in Eastern Europe. We probably could have done the same type of thing with Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam.

Is there anything we could have done to make the war turn out differently than it did? Possibly in the early, early days, if we would have really focused on the villages [pushing the Viet Cong out and then maintaining a presence there, while providing economic and military training assistance]. But how many times did we walk hills, blow them up, win everything and then leave it? They would come back again. We didn’t care.

Are there any political and military leaders you particularly admire? There are lots of military leaders and of government leaders that are pretty decent folk who try to do the right thing. Even in Vietnam, [Col. David] Hackworth [a critic of U.S. military commanders and policy] and some of these other guys were trying to tell people what was going on, and they didn’t want to listen. I think poor Johnson was put into a bad spot. He was trying to deal with poverty in the United States. And he was dealing with a freaking war that was costing him billions and bodies. And he was afraid to call up the college kids and make the draft universal, afraid of the Chinese, afraid of everything.

The 1960s and ’70s are remembered not only for the Vietnam War, but also for the pop culture of the era. What kind of music did you enjoy then? Rock. I liked The Who when I came back, Moody Blues, Chicago, lots of different groups.

How did you dress in those days? When I went back to college, I grew my hair down to my shoulders. I grew a beard immediately. Of course, bell bottoms and all that stuff. I remember I wore my big, blue Air Force overcoat in the wintertime going to school. It was heavy-duty serge wool, must have weighed 20 pounds. The funny part is I had never worn it in the military. I was never in a cold climate. So it here I am finally wearing my Air Force overcoat when I’m a civilian.

As the Vietnam generation ages, what’s the future of the Vietnam Veterans of America as an organization? It’s going to die someday. And we’re looking at that seriously. We have two working groups. One is figuring out how you go out of business gracefully over time. We’re going to look at the legal issues we’ve got to be concerned about. We also have a working group that’s looking at the feasibility of creating a new veterans organization, primarily with the younger veterans, that would continue some of the same ways of doing business that we do.

What do you mean by that? One of the differences between us and everybody else is we’ve been willing to sue. We’ve gone to court on lots of different things over the years, freedom of information stuff, Agent Orange issues, allowing those with less-than-honorable discharges into mental health programs.

And we’ve made sure that the folks who came home in the recent wars got a welcome. On many occasions the guys coming back at the airports were met by Vietnam vets. They thanked Vietnam vets for making sure they got what they deserved. That’s our motto: “Never again will one generation of veterans abandon another.” The old boys got pissed off at that [implied criticism of them]. Now we’re the old boys.

Residence: Middle Village (Queens borough), New York

Education: Queens College, bachelor’s in political science, 1970; Hunter College, master’s in urban affairs, 1972

Military service: U.S. Air Force, July 1965-December 1967; highest rank: sergeant

In Vietnam: June-July 1967; voice intercept processing specialist, 6988th and 6990th security squadrons

Professional career: Worked for Bronx Borough President Robert Abrams, 1973: community liaison for U.S. Rep. Ben Rosenthal, D-N.Y., 1973-77; district manager, Queens Community Board No. 4, 1977-85; chief investigator, New York City Council Office of Oversight and Investigation, 1985-96; manager-investigator, New York City Comptroller’s Office, 1996-2002

Today: Vietnam Veterans of America, president since 2005