The Vietnam War is the commonly used name for the Second Indochina War, 1954–1975. Usually it refers to the period when the United States and other members of the SEATO (Southeast Asia Treaty Organization) joined the forces with the Republic of South Vietnam to contest communist forces, comprised of South Vietnamese guerrillas and regular-force units, generally known as Viet Cong (VC), and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). The U.S., possessing the largest foreign military presence, essentially directed the war from 1965 to 1968. For this reason, in Vietnam today it is known as the American War.

It was a direct result of the First Indochina War (1946–1954) between France, which claimed Vietnam as a colony, and the communist forces then known as Viet Minh. In 1973 a “third” Vietnam war began—a continuation, actually—between North and South Vietnam but without significant U.S. involvement. It ended with communist victory in April 1975.

The Vietnam War was the longest in U.S. history until the Afghanistan War (2002-2014). The war was extremely divisive in the U.S., Europe, Australia, and elsewhere. Because the U.S. failed to achieve a military victory and the Republic of South Vietnam was ultimately taken over by North Vietnam, the Vietnam experience became known as “the only war America ever lost.” It remains a very controversial topic that continues to affect political and military decisions today.

Facts

when was the vietnam war?

1954–1975

LocationS

- South Vietnam

- North Vietnam

- Cambodia

- Laos

who won the vietnam war?

North Vietnam

Troop Strength

- South Vietnam: 850,000

- United States: 540,000

- South Korea: 50,000

- Others: 80,000+

Casualties

South Vietnam

- 200,000–400,000 civilians

- 170,000-220,000 military

- Over 1 million wounded

United States

- 58,200 dead

- 300,000 wounded

North Vietnam

- 50,000+ civilian dead

- 400,000–1 million military dead

- Over 500,000 wounded

more vietnam war Stories

how many people died in the Vietnam War?

The U.S. suffered over 47,000 killed in action plus another 11,000 noncombat deaths; over 150,000 were wounded and 10,000 missing.

Casualties for the Republic of South Vietnam will never be adequately resolved. Low estimates calculate 110,000 combat KIA and a half-million wounded. Civilian loss of life was also very heavy, with the lowest estimates around 415,000.

Similarly, casualty totals among the VC and NVA and the number of dead and wounded civilians in North Vietnam cannot be determined exactly. In April 1995, Vietnam’s communist government said 1.1 million combatants had died between 1954 and 1975, and another 600,000 wounded. Civilian deaths during that time period were estimated at 2 million, but the U.S. estimate of civilians killed in the north at 30,000.

Among South Vietnam’s other allies, Australia had over 400 killed and 2,400 wounded; New Zealand, over 80 KIA; Republic of Korea, 4,400 KIA; and Thailand 350 killed.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

North Vietnam, South Vietnam

Vietnam has a long history of being ruled by foreign powers, and this led many Vietnamese to see the United States’ involvement in their country as neo-colonialism. China conquered the northern part of modern Vietnam in 111 BC and retained control until 938 AD; it continued to exert some control over the Vietnamese until 1885. Originally, Vietnam ended at the 17th parallel, but it gradually conquered all the area southward along the coastline of the South China Sea and west to Cambodia. Population in the south was mostly clustered in a few areas along the coast; the north always enjoyed a larger population. The two sections were not unlike North and South in the United States prior to the Civil War; their people did not fully trust each other.

France’s military involvement in Vietnam began when it sent warships in 1847, ostensibly to protect Christians from the ruling emperor Gia Long. Before the 1880s, the French controlled Vietnam. In the early 20th century, Vietnamese nationalism began to rise, clashing with the French colonial rulers. By the time of World War II, a number of groups sought Vietnamese independence but as Vo Nguyen Giap—who would build Vietnam’s post–WWII army—expressed it, the communists were the best organized and most action-oriented of these groups.

During the Second World War, Vichy France could do little to protect its colony from Japanese occupation. Post-war, the French tried to re-establish control but faced organized opposition from the Viet Minh (short for Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi, or League for the Independence of Vietnam), led by Ho Chi Minh and Giap. The French suffered a major defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, leading to negotiations that ended with the Geneva Agreements, July 21, 1954. Under those agreements, Cambodia and Laos—which had been part of the French colony—received their independence. Vietnam, however, was divided at the 17th parallel. Ho Chi Minh led a communist government in the north (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) with its capital at Hanoi, and a new Republic of South Vietnam was established under President Ngo Dinh Diem, with its capital at Saigon.

The division was supposed to be temporary: elections were to be held in both sections in 1956 to determine the country’s future. When the time came, however, Diem resisted the elections; the more populous north would certainly win. Hanoi re-activated the Viet Minh to conduct guerilla operations in the south, with the intent of destabilizing President Diem’s government. In July 1959, North Vietnam’s leaders passed an ordinance called for continued socialist revolution in the north and a simultaneous revolution in South Vietnam.

Some 80,000 Vietnamese from the south had moved to the north after the Geneva Agreements were signed. (Ten times as many Vietnamese had fled the north, where the Communist Party was killing off its rivals, seizing property, and oppressing the large Catholic population.) A cadre was drawn from those who went north; they were trained, equipped and sent back to the south to aid in organizing and guiding the insurgency. (Some in the North Vietnamese government thought the course of war in the south was unwise, but they were overruled.) Although publicly the war in the south was described as a civil war within South Vietnam, it was guided, equipped and reinforced by the communist leadership in Hanoi. The insurgency was called the National Liberation Front (PLF); however, its soldiers and operatives became more commonly known by their opponents as the Viet Cong (VC), short for Vietnamese Communists. The VC were often supplemented by units of the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), more often called simply the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) by those fighting against it. Following the Tet Offensive of 1968, the NVA had to assume the major combat role because the VC was decimated during the offensive.

United States Military Advisers in Vietnam

The U.S., which had been gradually exerting influence after the departure of the French government, backed Diem in order to limit the area under communist control. Mao Zedong‘s Communist Party had won the Chinese Civil War in 1949, and western governments—particularly that of the U.S—feared communist expansion throughout Southeast Asia. This fear evolved into the “Domino Theory”; if one country fell to communist control, its neighbors would also soon fall like a row of dominos. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) advised that was not the case—America had a strong military presence in the Pacific that would serve as a deterrent. Earlier, “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the World War II forerunner of the CIA, had also advised that the U.S. had nothing to gain and much to lose by becoming involved in what was then French Indochina.

A different feeling prevailed among many within the U.S. government. The communist takeover of China and subsequent war in Korea (1950-53) against North Korean and Chinese troops had focused a great deal of attention on Southeast Asia as a place to take a strong stand against the spread of communism. During President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration (1953–1961), financial aid was given to pay South Vietnam’s military forces and American advisors were sent to help train them. The first American fatality was Air Force Technical Sergeant Richard B. Fitzgibbon, Jr., killed June 8, 1956. (His son, Marine Corps lance corporal Richard Fitzgibbon III would be killed in action in Vietnam September 7, 1965. They were the only father-son pair to die in Vietnam.) In July 1959 Major Dale Buis and Master Sergeant Chester Ovnand were off duty when they were killed during an attack at Bien Hoa.

Ho Chi Minh had been educated in Paris. There is considerable debate over whether he was primarily nationalist or communist, but he was not especially anti-Western. (An American medic treated him during World War II, probably saving his life.) Ho attempted to contact Eisenhower to discuss Vietnam but received no answer. “Ike” may not have seen the message, but at any rate he was focused on establishing NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) as a wall against additional communist advances in Europe and was intent on securing France’s participation in NATO. That would have made any negotiation with Ho politically ticklish. A lingering question of the war is what might have happened if Eisenhower and Ho had arranged a meeting; possibly, an accord could have been reached, or possibly Ho was simply seeking to limit American involvement, in order to more easily depose the Diem government.

American Military Involvement Escalates

American involvement began to escalate under President John F. Kennedy‘s administration (January 1961–November 1963). North Vietnam, had by then established a presence in Laos and developed the Ho Chi Minh Trail through that country in order to resupply and reinforce its forces in South Vietnam. Kennedy saw American efforts in Southeast Asia almost as a crusade and believed increasing the military advisor program, coupled with political reform in South Vietnam, would strengthen the south and bring peace. Two U.S. helicopter units arrived in Saigon in 1961. The following February a “strategic hamlet” program began; it forcibly relocated South Vietnamese peasants to fortified strategic hamlets. Based on a program the British had employed successfully against insurgents in Malaya, it didn’t work in Vietnam. The peasants resented being forced from their ancestral lands, and consolidating them gave the VC better targets. The program, which had been poorly managed, was abandoned after about two years, following the coup that deposed Diem.

Diem fell from favor with his American patrons, partly over disagreements in how to handle the war against the VC and partly because of his unpopular suppression of religious sects and anyone he feared threatened his regime. Buddhists, who comprised South Vietnam’s majority, claimed Diem, a Catholic, favored citizens of his religion in distributing aid. He, in turn, called the Buddhists VC sympathizers. On June 11, 1963, an elderly Buddhist monk named Thich Quang Duc sat down in the street in front of a pagoda in Saigon to protest Diem’s policies. Two younger monks poured a mix of gasoline and jet fuel over him and, as the three had planned, set fire to him. Associated Press correspondent Malcolm “Mal” Browne photographed him sitting quietly in the lotus position as the flames consumed him. The photo was published worldwide under the title “The Ultimate Protest,” raising (or in some cases reinforcing) doubts about the government that the democratic United States was supporting. Seven more such immolations occurred that year. To make matters worse, Diem responded by sending troops to raid pagodas.

In November, a coup deposed Diem, with the blessing of Kennedy’s administration, which had quietly assured South Vietnam’s military leaders it was not adverse to a change in leadership and military aid would continue. The administration was caught by surprise, however, when Diem was murdered during the coup, which was led by General Duong Van Minh. This began a series of destabilizing changes in government leadership.

That same month, Kennedy himself was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. His successor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, inherited the Vietnam situation. Johnson wanted to focus on instituting “Great Society” programs at home, but Vietnam was a snake he did not dare let go of. His political party, the Democrats, had been blamed for China falling to communism; withdrawing from Vietnam could hurt them in the 1964 elections. On the other hand, Congress had never declared war and so the president was limited in what he could do in Southeast Asia.

Gulf of Tonkin Incident

That changed in August 1964. On August 2, two North Vietnamese torpedo boats in broad daylight engaged USS Maddox, which was gathering communications intelligence in the Gulf of Tonkin. Two nights later, Maddox and the destroyer USS Turner Joy were on patrol in the Gulf and reported they were under attack. The pilot of an F-8E Crusader did not see any ships in the area where the enemy was reported, and years later crew members said they never saw attacking craft. An electrical storm was interfering with the ships’ radar and may have given the impression of approaching attack boats.

Congress swiftly passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that removed most restrictions from the president in regards to Vietnam. By year’s end, 23,000 American military personnel would be in South Vietnam. Though a congressional investigative committee the previous year had warned that America could find itself slipping into in a morass that would require more and more military participation in Vietnam, Johnson began a steady escalation of the war, hoping to bring it to a quick conclusion. Ironically, the leadership of North Vietnam came to a similar conclusion: they had to inflict enough casualties on Americans to end support for the war on the U.S. homefront and force a withdrawal before the U.S. could build up sufficient numbers of men and material to defeat them.

On September 30, 1964, the first large-scale antiwar demonstration took place in America, on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. The war became the central rallying point of a burgeoning youth counterculture, and the coming years would see many such demonstrations, dividing generations and families..

On Christmas Eve, in Saigon, a VC set off an explosive at the American officers’ billet in the old Brink Hotel, killing two Americans and 51 South Vietnamese. This would be a war without a front or a rear; it would involve full-scale combat units and individuals carrying out terrorist activities such as the Brink Hotel bombing. Both the Army of the Republic of South Vietnam (ARVN) and the VC used torture, to extract information or to cow opposition.

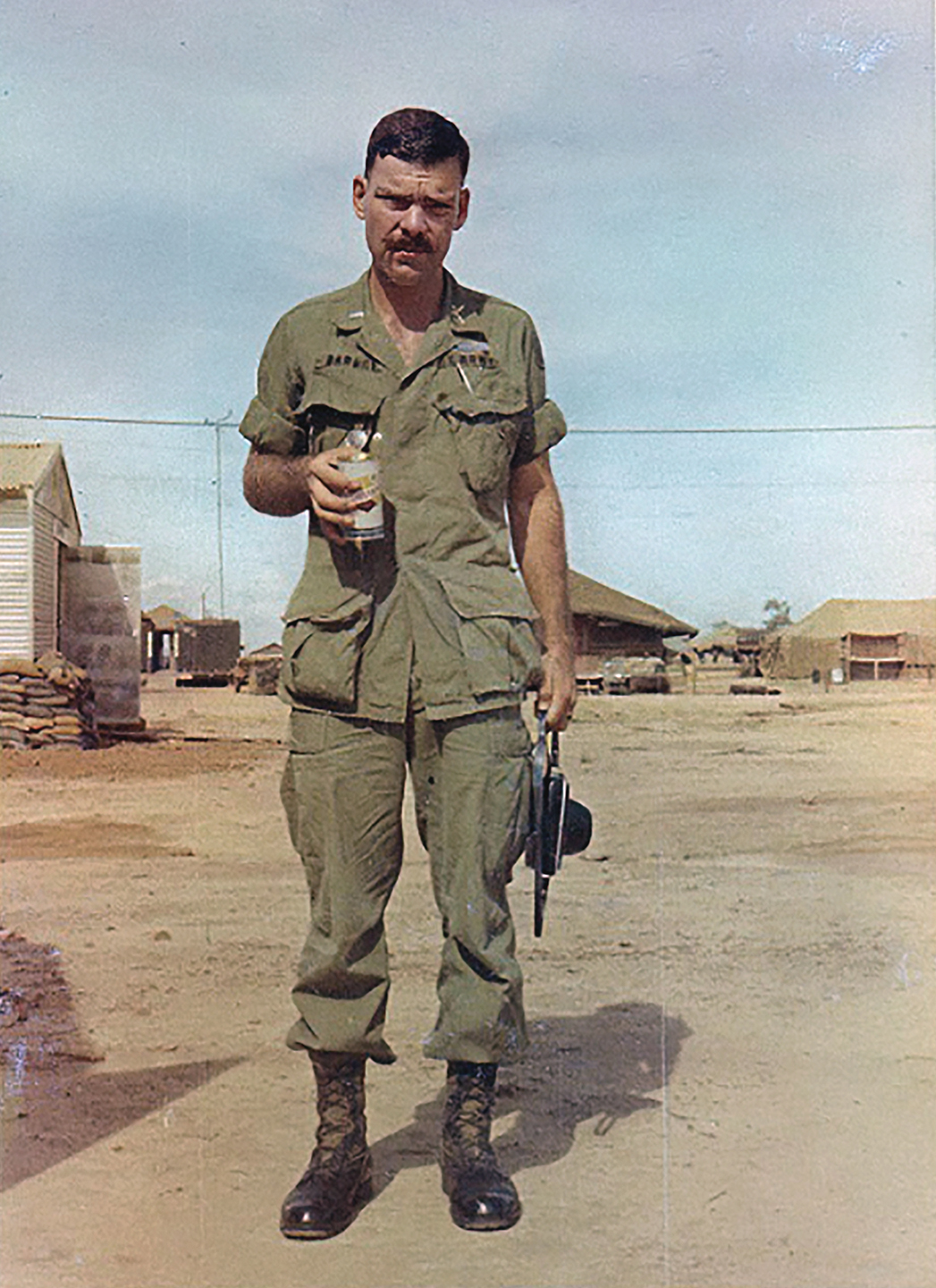

Gen. William C. Westmoreland

In previous war, progress and setbacks could be shown on maps; large enemy units could be engaged and destroyed. Guerrilla warfare (asymmetrical warfare) does not permit such clear-cut data. This presented the new MACV commander (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam), General William C. Westmoreland with a thorny challenge: how to show the American people progress was being made.

Westmoreland adopted a search-and-destroy policy to find and engage the enemy and use superior firepower to destroy him. Success was measured in “body count.” It was to be a war of attrition and statistics, a policy that suited Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who distrusted the military and often bypassed the Joint Chiefs of Staff in issuing directives. Every major engagement between U.S. forces and VC or NVA was an American victory, and the casualty (body count) ratio always showed significantly larger casualties for the communist forces than for the Americans. The body count policy fell into disfavor and was not employed in future American wars; in Vietnam it led officers to inflate enemy casualties. The VC and NVA dragged off as many of their dead and wounded as possible, sometimes impressing villagers into performing this task during battles, so determining their casualties was guesswork based on such things as the number of blood trails.

On the other side, the same thing was occurring, with even more inflated numbers—vastly more. Both sides were fighting a war of attrition, so communist commanders sent Hanoi battle reports that often were pure fantasy. One example, cited in Grab Their Belts to Fight Them: The Viet Cong’s Big-Unit War Against the U.S., 1965–1966, by Warren Wilkins (Naval Institute Press, 2011), is a description of the first major battle between the VC and American Forces—U.S. Marines—near Van Truong, from the VC point of view. It claimed,”In one day of ferocious fighting we had eliminated from the field of battle a total of 919 American troops, had knocked out 22 enemy vehicles and 13 helicopters, and had captured one M-14 rifle.” Marine losses actually were 45 dead, 203 wounded, and a few vehicles damaged.

On February 7, 1965, the U.S. Air Force began bombing selected sites in North Vietnam. This grew into the operation known as Rolling Thunder that began on March 2, 1965, and continued to November 2, 1968. Its primary goal was to demoralize the North Vietnamese and diminish their manufacturing and transportation abilities. An air war was the most that could be done north of the 17th parallel, because the use of ground troops had been ruled out. North Vietnam was a prodigy of both the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and Red China. On July 9, 1964, China had announced it would step in if the U.S. attacked North Vietnam, as China had done in the Korean War. North Vietnamese officers, after the war, said the only thing they feared was an American-led invasion of the north, but the U.S. was not going to risk starting World War III, and at the time that seemed to loom as a distinct possibility.

Tet: the Turning Point

By the end of 1967, there were 540,000 American troops in Vietnam, and the military draft was set to call up 302,000 young men in the coming year, an increase of 72,000 over 1967. Financial costs had risen to $30 billion a year. But the war news was hopeful. The South Vietnamese Army was showing improvement, winning 37 of their last 45 major engagements. American troops had won every major battle they fought, and General Nguyen Van Thieu had come to power in South Vietnam in September; he would remain in office until 1975, bringing a new measure of stability to the government, though he could not end its endemic corruption. Antiwar protests continued across America and in many other countries, but on April 28, 1967, Gen. Westmoreland became the first battlefield commander ever to address a joint session of Congress in wartime, and Time magazine named him Man of the Year. In an interview he was asked if there was light at the end of the tunnel, and he responded that the U.S. and its allies had turned a corner in Vietnam.

On January 30, 1968, during Vietnam’s celebration of Tet, the lunar new year, VC and NVA units launched a massive attack in every province of South Vietnam. They struck at least 30 provincial capitals and the major cities of Saigon and Hue. American intelligence knew an attack was coming, though the Army had downplayed a New York Times report of large communist troop movements heading south. The timing and scale of the offensive caught ARVN, the U.S. and other SEATO troops by surprise, however. They responded quickly, recapturing lost ground and decimating an enemy who had “finally come out to fight in the open.” Communist losses were extremely heavy. The VC was effectively finished; it would not field more than 25,000–40,000 troops at any time for the remainder of the war. The NVA had to take over. It was one of the most resounding defeats in all of military history—until it became a victory.

News footage showed the fighting in Saigon and Hue. The Tet Offensive shocked Americans at home, who thought the war was nearing victory. Initially, however, homefront support for the war effort grew, but by March Americans, perceiving no change in strategy that would bring the war to a conclusion, became increasingly disillusioned. CBS evening news anchor Walter Cronkite returned to Vietnam to see for himself what was happening. He had been a war correspondent during World War II and had reported from Vietnam during America’s early involvement. In 1972 a poll determined he was “the most trusted man in America.”

In a February 27, 1968, broadcast he summed up what he had found during his return trip to the war zone. He closed by saying:

To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion. On the off chance that military and political analysts are right, in the next few months we must test the enemy’s intentions, in case this is indeed his last big gasp before negotiations. But it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.

President Johnson, watching the broadcast, said, “If we’ve lost Walter Cronkite, we’ve lost the country.” In May, Johnson announced he would not run for reelection. He also said there would be a pause in the air attacks on North Vietnam as “the first step to de-escalate” and promised America would substantially reduce “the present level of hostilities.”

Adding to Americans’ disillusionment was the race issue. Tensions between Blacks and whites had been intensifying for years as African Americans sought to change centuries-old racial policies. The Civil Rights Movement had produced significant victories, but many Blacks had come to describe Vietnam as “a white man’s war, a Black man’s fight.” Between 1961 and 1966, Black males accounted for about 13 percent of the U.S. population and less than 10 percent of military personnel but almost 20 percent of all combat-related deaths. That disparity would decline before the war ended, but the racial tensions at home began to insert themselves into the military in Vietnam, damaging unit morale.

Even white troops were beginning to protest. One day in October 1969, fifteen members of the Americal Division wore black armbands while they were on patrol, the symbol antiwar protestors wore in the states. Earlier, in March 1968, the Americal Division had been involved in what became known as the My Lai Massacre, in which over 100 men, women and children were killed. Similar, even larger, atrocities were conducted by VC and NVA units—such as an NVA attack on a Buddhist orphanage at An Hoa in September 1970 or the execution of 5,000 people at Hue during the Tet Offensive—but the concept of American soldiers killing civilians in cold blood was more than many Americans could bear. Support for the war eroded further. Some antiwar protestors blamed the men and women who served in Vietnam, taunting them and spitting on them when they came home. Military personnel, including nurses, were warned not to wear their uniforms in the States. However, polls consistently showed the majority of Americans supported the war.

Richard Nixon’s War

Republican Richard Nixon won the presidency in the fall elections. Emphasis switched to “Vietnamization,” preparing South Vietnam’s military to take over responsibility for continuing the war. Gen. Westmoreland had been promoted to Army Chief of Staff and replaced in Vietnam by Gen. Creighton Abrams. For the first time, MACV worked with South Vietnam’s government to create annual plans. Security was improving even as American forces were in the process of withdrawing.

Then, on March 30, 1972, the North Vietnamese attacked across the 17th parallel with 14 divisions and additional individual regiments. Better armed than ever before, thanks to increased aid from the Soviet Union, they employed tanks for the first time.

The ARVN bent but did not break. By June they had stalled the invasion, with the help of American airpower. The NVA suffered some 120,000 casualties. American drawdown continued, with only 43,000 personnel left in-country by mid-August.

In retaliation for the invasion, and in hopes of forcing Hanoi to negotiate in good faith, Nixon ordered Haiphong harbor in North Vietnam to be mined and he intensified bombing of North Vietnam. Hanoi offered to restart peace talks, yet remained intransigent in its demands. Frustrated, Nixon ordered the big bombers—B-52s—to strike Hanoi, beginning December 16 (Operation LINEBACKER). In less than two weeks, these strategic bombers had shattered the north’s defenses. On January 27, 1973, peace accords were signed between North Vietnam and the U.S.

The ceasefire allowed Nixon to declare “peace with honor,” but no provisions existed for enforcing the terms of the accords. North Vietnam spent two years rebuilding its military; South Vietnam was hamstrung in its responses by a fear the U.S. Congress would cut off all aid if it took military action against communist buildup. Its army lacked reserves, while the NVA was growing.

On March 5, 1975, the NVA invaded again. ARVN divisions in the north were surrounded and routed. No American air strikes came to aid the overstretched South Vietnamese, despite Nixon’s earlier assurances to Thieu. To its own surprise, Hanoi found its forces advancing rapidly toward Saigon, realized victory was at hand, and renamed the operation the Ho Chi Minh Offensive. On April 30, their tanks entered Saigon. American helicopters rescued members of its embassy and flew some South Vietnamese to safety, but most were left behind. North and South Vietnam were combined into the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in 1976.

The domino fell but did not take down any of those around it. Although America’s war in Vietnam failed to salvage the Republic of South Vietnam, it bought time in which neighboring countries improved their economies and defensive capabilities, and it may have discouraged greater communist activism in places like the Philippines.

The Media and Vietnam

One of the lingering legacies of the Vietnam War is the widespread belief in America that “the media cost us the war in Vietnam.” Images such as the burning monk; South Vietnamese Police Chief Lt. Col. Nguyen Ngoc Loan about to pull the trigger of a pistol pointed at the head of a bound VC prisoner; of a naked young girl running crying down a road after an American napalm strike that left her badly burned—these images and others became seared into the minds of Americans on the homefront, and in those of civilians in allied nations such as Australia.

Never before or since have journalists been given such complete access to cover a war. Unlike previous wars, where only still images or short movie newsreels were available for conveying images, this was America’s first television war. Images of fighting, of dead and wounded soldiers, of POWs held in North Vietnam were beamed into America’s living rooms night after night, as was footage of hundreds, sometimes thousands of antiwar protestors marching through the streets. Such images pack tremendous emotional punch but often lack context. The photo of the South Vietnamese police chief, for example, cannot by itself explain he had just seen the dead body of a close friend minutes before; even Eddie Adams, the photojournalist who snapped the photo felt it unfairly maligned Lt. Col. Loan.

Undoubtedly, news media played an important role in Americans saying, “Enough.” Indeed, Vo Nyugen Giap had always envisioned using media as one of his spear points for victory. He has written that he was prepared for a 25-year war; he realized he did not have to achieve military victory; he only had to avoid losing.

Yet, to say the media cost America victory in Vietnam is vastly oversimplifying a very complex situation. As noted above, a number of sources warned U.S. leaders against becoming embroiled in Southeast Asia. Corruption and instability in South Vietnam’s government did not instill confidence in its people, or in the Americans working with it. Ruling out an invasion of North Vietnam assured that a purely military victory would not be possible, a fact that was at odds with many Americans’ expectations for the war.

The Vietnam War remains a very controversial subject. It is unlikely historians will ever agree on whether it was necessary or what benefits derived from it.