Fitz John Porter’s arrival at the U.S. Military Academy in 1841 gave him a perfect opportunity to erase the black mark his alcoholic father had left on his family’s name, and he made the most of it. Only a quarter of the young men who reported to West Point alongside Porter would graduate with their class, with the New Hampshire native ranking eighth out of 41 cadets in the Class of 1845.

Less than a year later, Porter landed on the coast of Texas, and in the spring of 1847 his regiment joined Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott for the U.S. Army’s campaign against Mexico City during the Mexican War. Porter helped guide artillery into position for the assault at Cerro Gordo, took part in the 4th Artillery’s epic bayonet charge at Contreras, and was even knocked unconscious by spent grapeshot at the Garita de Belén in the final assault on Mexico City.

Porter ended the war as a first lieutenant, with brevets as captain and major. Assigned to the West Point faculty in early 1849, he remained at his alma mater more than six years as an instructor of “natural and experimental philosophy,” artillery, and cavalry tactics. Toward the latter part of his sojourn there, he stood in as acting adjutant for the academy’s superintendent, Robert E. Lee.

Frustrated, however, by the glacial pace of promotion, Porter relinquished his seniority as a line officer in 1856 to accept an appointment in the adjutant general’s office, which would take him to Kansas Territory during the hunt for abolitionist John Brown. Then, in the autumn of 1857, he served as chief of staff to Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston during the Utah Expedition. After a brutal winter in the mountains on short rations, Johnston’s force marched into Salt Lake City in 1858, establishing a military post and spending the next two years amid a covertly hostile Mormon population.

After returning to New York via California and Panama in 1860, Porter played a part in some of the more renowned preludes to the Civil War. As secession loomed that November, he inspected federal facilities in Charleston, S.C., and recommended a more energetic officer to command it—which led to the assignment of Major Robert Anderson. Early in 1861, Porter sailed to the mouth of the Rio Grande to help bring home hundreds of U.S. troops trapped by the secession of Texas.

With the war’s outbreak in April, Scott, serving as Lincoln’s chief military adviser, sent Porter to Harrisburg, Pa., to organize volunteers. On April 22, while in the Pennsylvania capital, Porter intercepted a telegram indicating that the Army’s department commander in St. Louis, a suspect Southerner, had impeded the mustering of volunteers to protect the U.S. arsenal there. Audacity had always been part of Porter’s personality. On his own initiative, he issued orders in Scott’s and Secretary of War Simon Cameron’s names to muster in those volunteers.

Through the summer of 1861, Porter served as chief of staff to Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson, whose missteps as a commander in the Shenandoah Valley contributed to the Federals’ stunning defeat at First Bull Run on July 21. Promoted to brigadier general in August, Porter assumed command of a division in the Army of the Potomac. By autumn, it was widely recognized as the best-drilled in the entire army.

Before long, Porter became the favored adviser of his commanding officer, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, a former West Point comrade. During the Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862, McClellan elevated Porter to 5th Corps command, and his reliance on Porter was soon evident—to the displeasure of the army’s more senior generals. Porter led the Federals’ first clear victory in the campaign in an engagement at Hanover Court House, Va., and also commanded Union forces in a tactical victory at Malvern Hill during the Seven Days Campaign in late June-early July.

Despite Porter’s success at Malvern Hill, the Seven Days would be a calamitous defeat for McClellan, who having failed to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond was ordered to pull his army back to Washington. On August 16, Porter’s corps was instructed to join Maj. Gen. John Pope’s newly created Army of Virginia. On August 29, during the Second Battle of Bull Run, Porter halted a risky noontime assault at the behest of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell, commander of that army’s 3rd Corps. Later that day, Porter called off what he considered a more injudicious attack Pope had ordered, insisting the general was mistaken in doing so—ignorant of enemy dispositions.

Second Bull Run proved another devastating Union defeat, and Pope would be quick to blame it on Porter’s inaction at critical points of the battle, accusing his subordinate of deliberate subversion. A political element became entwined in the fallout from the defeat, particularly when information reached the White House about pre-battle correspondence from Porter—like McClellan, a conservative Democrat—revealing his poor opinion of Pope. That would be presented as evidence of Porter’s guilt when he was finally brought before a court-martial on November 25, 1862.

That court-martial is perhaps unequaled in American military history. Although it wasn’t settled until January 22, 1863—nearly two months after it began—Porter was likely doomed from the start. He would be convicted of criminal disobedience of orders and misbehavior before the enemy, and dismissed from the Army in disgrace.

For the next 35 years, Porter worked as a mining engineer and construction superintendent, as New York City’s director of public works and one of its police and fire commissioners, and as the treasurer of private corporations and the New York Post Office. He devoted the bulk of his leisure time to a determined crusade to clear his name. Pope and his cronies blocked Porter’s every request for a rehearing until 1878, when President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed a board of officers to review the case.

Those officers dismissed every accusation made against Porter in his court-martial, characterizing his Second Bull Run performance as prudent and obedient, and recommending his reinstatement. But Republican congressman James Garfield of Ohio, who as a brigadier general had sat on the 1862 court-martial, worked behind the scenes to deny Porter hope of justice, continuing to denounce the dishonored general, probably to further his own presidential ambitions. In 1881, after Garfield was assassinated four months into his presidency, Senator John A. Logan—another former Union general and presidential aspirant—continued Garfield’s vendetta.

Finally, in 1886, Porter was restored to his old Regular Army rank of colonel and retired immediately. He never received a penny of back pay or retirement, having waived such reward for service in hopes of restoring his good name, as he had always desired. But his success was limited. Thanks to the efforts of Garfield and Logan, doubts about Porter’s honesty and faithfulness persisted a century after his death.

Porter’s abrupt fall from military prominence was startling considering his pedigree and his momentous start in the war. The Union army’s inaugural disaster at First Bull Run in July 1861 had emphasized the need for better training and discipline—and for organizational genius—which brought Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan to Washington to take command of the army. McClellan recommended numerous acquaintances from the antebellum Army for appointments as brigadier generals, including Porter, Porter’s West Point classmates Charles P. Stone and William F. “Baldy” Smith, and William B. Franklin. Upon Porter’s arrival in Washington in late August, McClellan handed him a two-brigade division—assigned to Fort Corcoran, a log-and-earthwork bastion constructed on the heights of Arlington, Va., across the Potomac River from the capital.

There had already been trouble in three of Porter’s regiments. Hundreds of the men believed they had enlisted for three months’ service only to learn they had been mustered in for two years. Many refused to perform any more duty after the last of the 90-day militia went home. Only days before, Porter’s predecessor had confronted the disaffected camps with Regular cavalry and a battery of charged guns, taking the most stubborn mutineers away in irons.

These sullen soldiers composed one-third of Porter’s new command. The 13th New York evinced the greatest bitterness, and equipment shortages deepened their resentment. Desertions, dismissals, and discharges—not to mention arrests—had reduced the regiment to barely a third of its complement.

Porter, whom one volunteer officer called “the extreme West Pointer,” imposed a series of courts-martial as he strove to improve discipline. He had several dozen officers and men from the 13th, 14th, and 41st New York and the 9th Massachusetts regiments arrested, for offenses ranging from minor insubordination to mutiny and assault with a deadly weapon. Over the next 10 weeks, different courts cashiered officers and sentenced men to drumming out of camp or hard labor with ball and chain for anywhere from two months to a year.

Two new brigadier generals joined him the first week. John Martindale and George W. Morell, both 46-year-old New Yorkers, had graduated together in the West Point Class of 1835, Morell ranking first and Martindale third. Both had also quickly left the Army: Martindale never served on active duty, and Morell spent two years in the Engineers. Both then practiced law in their native state. Now, both commanded brigades under Porter.

Porter imposed a rigorous training schedule, alternating drill with fatigue duty, and he emphasized bayonet practice. He roused the men at all hours to respond to real or imagined alarms, hardening them to the rigors and uncertainty of soldiering. Much like the commander of his army, he emphasized vigilance against an enemy he assumed to be much stronger than it was. From the start, McClellan had tended to credit exaggerated estimates of Confederate strength, and his closest subordinates shared that credence, including Porter. On September 13, 1861, McClellan reported that the enemy had amassed as many as 170,000 men in front of the Union army’s lines in Arlington, Va., and was about to spring. In fact, barely 35,000 Confederates stood present for duty within striking distance of Washington.

Porter took keen interest in a novel means of observing the enemy. Thaddeus S.C. Lowe, known as the “Professor,” offered his services to the government as an aeronaut. After bringing his hydrogen balloon to the Virginia side of the Potomac, Lowe made his first ascent from Fort Corcoran within hours of Porter’s arrival there. He took General McDowell aloft, and on the sultry afternoon of September 4, Porter went up over the fort with them. From an elevation of 800 feet, they could see Confederates digging earthworks on Upton’s and Munson’s Hills, a few miles in advance of the constricted Union perimeter.

Over the next week, Porter asked Lowe to make an observation nearly every clear day. He arranged for the balloon to go up where McClellan and other prominent officers could see it in action, advising Lowe to make the most of the demonstration, and when it went well he assured Lowe that he was “of value now.” Porter recommended more balloons, pointing out that such reconnaissance would prevent any significant number of the enemy from approaching unseen within eight or ten miles. “It costs several lives now to obtain a portion of the information which may be derived by means of the balloon,” he noted.

The first aerial surveillance for active operations took place on September 25 when Baldy Smith, whose division lay on Porter’s right, launched a foraging expedition to the village of Lewinsville. Porter sent Lowe up to watch for enemy interference, but the Confederates seemed preoccupied with parading their troops for spectators crowding the slope of Munson’s Hill.

McClellan coveted Munson’s and Upton’s hills, in the middle of the Confederate line, to the left of Porter’s position, and Lowe’s surveillance may have led the enemy to suspect as much. On September 28, Union pickets before Munson’s Hill detected that their Rebel counterparts had slipped away, and McClellan sent orders to ease forward cautiously. A Michigan regiment swept up the hill and seized the abandoned works, which it turned out had served mainly as an observation post, with “artillery” consisting of painted logs and pasteboard tubes—so-called “Quaker Guns.”

As other troops occupied Munson’s and Upton’s hills, Porter moved one brigade three miles forward from Fort Corcoran and seized two taller crests in the western corner of D.C.’s original boundary. He bivouacked most of the brigade on Hall’s Hill, where he and his staff slept under a tree the night they occupied the place. His pickets also occupied Minor’s Hill, a couple of miles away, which offered the highest vantage point within the old district line. From there Porter could look down on Falls Church, where Rebels had left rumors behind to discourage pursuit. Inhabitants told Porter that Confederate leaders had recently discussed plans to pull back to a stronger position and thus lure McClellan into pursuit, hoping to pounce on him with 175,000 men.

Porter had called Alexandria home for some years. He probably credited the local inhabitants with greater fidelity than the times warranted, and his credence in them may have helped McClellan to accept such inflated numbers. Porter tried to cultivate spies and informants wherever he served, but some of his operatives proved useless, or worse. Lest they be caught by surprise, Professor Lowe began making observations from Upton’s Hill almost immediately, taunting the Rebels with the portrait of General McClellan painted on his balloon, Intrepid.

On October 10, Porter moved his staff and the rest of his division from Fort Corcoran to Hall’s Hill. His division had just been augmented by a third brigade commanded by Daniel Butterfield, an antebellum officer of gentlemen militia and the son of the founder of the Butterfield Overland Mail Company. Porter had met him in the summer campaign, as colonel of the 12th New York. Judging Butterfield a strict disciplinarian and an effective drillmaster, Porter had suggested him to McClellan.

Over the next several months, Porter devoted most of his attention to drilling the troops and acquainting himself with the officers of the dozen infantry regiments in his division. McClellan had given him two regiments of Pennsylvania volunteer cavalry, with experienced officers from the West Point Class of 1855 commanding both, and Porter’s artillery consisted of two Regular Army batteries.

The volunteer infantry brought the greatest trouble in the way of undesirable officers. In Martindale’s brigade, the 13th New York began floundering again, and Porter court-martialed more officers, forcing others to resign. The latest of several colonels who commanded that regiment was John Pickell, who had graduated from West Point two months before Porter was born but had been out of service for decades. Colonel Pickell harbored intense abolitionist sentiments, and when a cavalry officer from Washington brought his own slave to the camp at Hall’s Hill, Pickell lured the lad away and hid him in his quarters. Porter ordered Pickell to turn the youth out, and the old man surreptitiously raised a stink over it.

Porter eventually asked a board to examine Pickell’s fitness for service. Pickell had solicited an appointment as brigadier general, but Porter gently suggested that the old man was already expending “as much energy as his age and bodily strength will permit.” The examining board showed less tact, finding him pathetically deficient, and one officer recorded that Pickell was “the merest child in his profession: he could not answer the simplest questions.” He was particularly deficient as an administrator, and his muster rolls were a shambles, carrying enlisted men as officers while vacant commissions went unreported. The man acting as adjutant of his regiment turned out to be a private.

Pickell was summarily discharged. Porter’s confirmation as brigadier general came under attack by Radical Republican senators soon thereafter, and Porter understood that Pickell had carried to them an exaggerated tale about the runaway slave.

Insubordination was the rule in the 25th New York, which reportedly consisted of “New York roughs, Bowery boys, ‘Dead Rabbits,’ etc.” Desertions averaged three a week for two years, including the major and quartermaster. Colonel James E. Kerrigan, a Tammany Democrat freshly elected to Congress, finagled commissions for three of his brothers and ruled the regiment like a gang, ignoring both drill and discipline.

Martindale, whose brigade also encompassed this problem regiment, inspected it in mid-October and reported it in abominable condition. Officers and men were drinking, arguing, and fighting, and when called into formation many of those in the ranks stood half-dressed and barefoot. In defiance of Martindale’s direct order, Colonel Kerrigan refused to stand inspection with them. Martindale had him arrested.

Kerrigan enjoyed the loyalty of his most obstreperous men, who might resist any effort to confine him. On October 18, Porter called the 25th New York into line and brought all his nearby regiments out under arms while a guard detail seized Kerrigan and escorted him to Washington.

Porter supported Martindale’s efforts to weed incompetents out of the 25th and promote promising officers. Two of Kerrigan’s brothers resigned immediately after his arrest, and the third was fatally wounded—by whom was never established. Over the next few weeks, more than a dozen officers left the regiment, including a surgeon who had been filching from the hospital fund. Private soldiers who still refused to go on duty were given the choice of compliance or prison, and most submitted. Another man took temporary command, and his strict discipline momentarily accelerated the desertion rate, but the erstwhile mob started to look military.

Just as Porter relied on firmness and competence among his regimental and brigade commanders to mold their men into trustworthy components of his division, McClellan needed generals with similar talents to lead his divisions. Porter was hardly the most senior of McClellan’s generals, but many thought him the best of the lot, and some already suspected that he was the commanding general’s favorite. His calm and thoughtful nature made him a valuable confidant and counselor. His talent for training raw recruits and reconciling them to strict discipline gave McClellan an excellent opportunity to showcase the development of his army—and McClellan needed such a display by late October, after a disastrous little battle at Ball’s Bluff, near Leesburg, Va., where Charles P. Stone’s division had taken a pounding.

Porter proposed a review for Saturday, October 26, with a division drill and sham battle. He formed his three brigades, batteries, and cavalry in a 25-acre field, with McClellan and his staff in attendance. Porter led the various brigades through the evolutions of drill, maneuvering them by regiment, battalion, company, and file, and finally formed them in double ranks, three brigades deep. From there they wheeled out by companies and marched before the assembled visitors, then resumed their formation. McClellan and his guests trotted between the ranks, and as they approached each regiment its band would erupt in brass and percussion, falling silent as the next band began another selection.

For the finale, Porter deployed the division in line of battle, bringing each company into line by regiment at the double-quick. Each rank loosed a blank volley before retiring behind another rank to load, while the new front rank fired in turn. The sound of the exercise carried into the streets of Washington, where the unexpected echo of gunfire roused apprehension.

Three members of the Orléans family, claimants to the throne of France, attended the review. François d’Orléans, the somewhat deaf Prince de Joinville, rode along as a civilian observer and deemed himself an unofficial consultant to McClellan. His young nephews, Philippe d’Orléans (nominally the Comte de Paris) and Robert d’Orléans (the Duc de Chartres), held volunteer commissions as captains, with appointments as aides-de-camp to McClellan. These nomadic noblemen saw life at McClellan’s headquarters from a unique perspective, and Philippe kept a dense journal of his adventure.

The troops moved with admirable speed, thought Philippe. Of the brigadiers, he deemed Martindale “the true soldier, glaring always and swearing without cease, but briskly leading his brigade.” The prince considered Butterfield “the beau of New York transformed into a general.” He saw nothing noteworthy about Morell, but he thought Porter might be the most distinguished man in the army, “slim and delicate in appearance, with a black beard and a small and lively eye.” Porter evinced a reserved but determined air, according to the rightful king of France, and he maneuvered his troops “perfectly.”

That review of Porter’s division came just as McClellan expected to assume command of the entire U.S. Army, in place of General Scott. Scott intended to retire once an acceptable replacement appeared, and McClellan considered himself eminently acceptable. He led three Republican senators to believe Scott was impeding his efforts to move against the enemy, and those senators waited on the president, urging him to shelve the old general.

McClellan spent most of October 31 with Edwin M. Stanton, composing a report for Secretary Cameron designed to persuade the president to name him general-in-chief. Stanton, who had briefly served in James Buchanan’s Cabinet, had begun ingratiating himself to McClellan soon after the general reached Washington. He drafted the opening part of McClellan’s report, which ended with the suggestion that Cameron show it to the president. When it was finished, McClellan and one of the French princes rode away to Hall’s Hill—“to seek refuge in Fitz Porter’s camp,” as McClellan told his wife. The three of them sat around the campfire late into the night while the two generals digested the news and discussed the possibilities. The next day Scott formally retired, and Lincoln appointed McClellan “to command the whole Army.”

Porter never recorded his thoughts about the retirement of Scott, whom he had seemed to hold in high esteem until Scott turned on Patterson, Porter’s former commander in the spring and summer of 1861. Thereafter he had begun finding fault with Scott’s tactical and administrative wisdom in letters to Manton Marble, the influential Democratic editor of the New York World. McClellan’s personal annoyance with Scott did not improve Porter’s image of the old hero, and Porter may have been prodding Marble to editorial criticism for McClellan’s benefit. Porter gave McClellan the same loyalty he usually accorded his superiors, but his personal affection and his faith in McClellan’s ability enhanced the intensity of that professional obligation. McClellan reciprocated both Porter’s friendship and his confidence, regarding him privately as his chief subordinate and causing them both trouble by betraying that view through word and deed.

On his fourth morning as general-in-chief, McClellan met the division commanders of the Army of the Potomac at his lodgings in Washington. Mathew Brady came to photograph all the generals alongside the Young Napoleon, as friendly newspapers were calling McClellan. The weather was clear and unseasonably warm, so they sauntered outside, using the rear wall of the house for a backdrop. Baldy Smith, Franklin, Samuel P. Heintzelman, Andrew Porter, and McDowell lined up on McClellan’s right, with George McCall, Don Carlos Buell, Louis Blenker, Silas Casey, and Porter on his left.

Philippe d’Orléans regarded McDowell as “simple, frank, and affable,” but showed less enthusiasm for McCall, who was nearly 60 and slowing down. He described Casey as “an old man with a head like a bald parrot, who mounts a horse like a sick monkey.” The prince heard it said that Buell and Porter were the best generals with the army at Washington, and he left no doubt that Porter had surpassed everyone in training his troops. Porter had the best-looking division in the army, thought the prince, and McClellan took enormous pride in it.

Porter’s division elicited grand compliments after a review McClellan arranged for November 9. It was raining, but Porter ignored the weather. His men followed the same choreography they had performed two Saturdays previously, including the sham battle, while the mud deepened beneath their feet. From lines of battle they swung into hollow squares, and once again the hillsides echoed with the dull, damp reverberations of musketry and cannon. The men marched back to camp at midafternoon drenched to the skin, but a week later McClellan issued a general order praising their proficiency in drill. He called Porter’s division “a model for the Army,” evidently hoping to initiate competition among other commands, but he also aroused jealousy among some of the older division commanders.

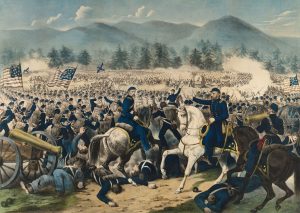

November 20 provided the premier military spectacle thus far in the war. Official Washington took a holiday, and all morning carriages crowded across the Long Bridge and down the Columbia Turnpike to Bailey’s Cross Roads, at the junction of the Leesburg Pike. There, on a broad and relatively level plain below Munson’s Hill, seven divisions—more than 60,000 men—formed ranks as a thick morning fog dissipated. The president and his family came, with most of the Cabinet and department functionaries galore. Thousands of spectators ringed the field. McClellan galloped onto the field at the head of a brigade of cavalry as 40 acres of massed troops cheered him. Batteries fired salutes, raising clouds of acrid smoke. After a barrage of anthems and accolades, McClellan, the president, and a long gaggle of officers and hangers-on mounted horses and threaded their way at a gallop through the long, deep ranks.

Many of the civilians clung nervously to their saddles. Lincoln rode with his elbows tucked into his sides, wrote the Comte de Paris, holding his hat out before the faces of the troops like a blind man begging. The tour consumed as much as an hour and a half, after which the riders returned to a rise at the front of the massive formation and gathered to watch as the army peeled off, one regiment or battery at a time, and marched past on its way to camp. When the last man had passed, one of the president’s private secretaries realized that it must have been the largest military parade the continent had ever seen.

The great review of November 20 demonstrated an impressive degree of competence in the army. Important people began wondering why it was not put to use, and early in December, Lincoln gently questioned McClellan about moving against General Joseph Johnston, who had assumed command of Confederate troops in northern Virginia. Then Congress reconvened, establishing a joint committee to investigate the conduct of the war. Republicans filled all but two of the seats, and the committee was soon dominated by Senators Ben Wade of Ohio and Zachariah Chandler of Michigan—the most visible and vocal of the Radical Republicans, who sought to steer the war toward abolition.

William Doubleday, whose cousin Abner had been at Fort Sumter, caught Chandler’s ear. The Doubledays were thoroughgoing abolitionists, and William offered Abner’s testimony to what he called the “proslavery” attitudes of McClellan, Porter, and dozens of other generals whose appointments would be coming to the Senate for confirmation. Chandler took the hint, especially in regard to McClellan and Porter.

As December progressed, the Comte de Paris claimed he knew McClellan had a campaign planned, and meant to launch it soon, but Porter allowed his men to build winter huts and McClellan asked him to parade his division again on December 21. McClellan’s wife had come to Washington, and attended the review. When it was over, Porter provided a banquet for McClellan, his wife, and their staffs. Two days later, McClellan came down with typhoid fever that he may have contracted at the feast. Headquarters tried for some time to pass McClellan’s illness off as a severe cold, but he grew worse for a week and could hardly leave his bed for over two weeks. His father-in-law and chief of staff had it, too, so there was no one to tell the president what should be happening to prepare the army for the field, or where it should go.

The joint committee immediately began interrogating McClellan’s troop commanders, and Porter testified late on December 28. Wade, Chandler, and the rest wanted to know whether the army could move against the enemy immediately and, if not, why. Porter said that as a division commander he knew little about the army as a whole, but he did suggest that the army could benefit from more preparation.

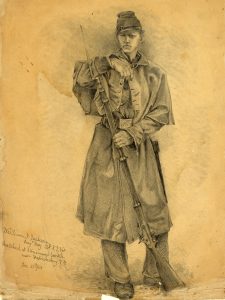

His own division illustrated how much the army could benefit. Porter’s distant, dignified manner, stern discipline, and attention to training had won the admiration and affection of men even in his most rebellious regiments. The adjutant of the once-mutinous 13th New York assured his brother that Porter commanded “the best 13,000 soldiers in the world,” and he described “Fitz John” as something of a father figure.

“A handsome man he is, slender but erect. A few gray hairs among his raven locks, a full black beard kept neatly trimmed, an eye like a diamond, slow and deliberate in his speech, with a low, clear, distinct utterance, prompt and decisive in his actions. Cold, heartless, unimpassioned, and a terrible, terrible, terrible disciplinarian….But such a splendid soldier….Ed, I honor, admire, revere, and could almost devote my life for that man.” Porter evidently had the magic touch.

Still, the president grew increasingly anxious about McClellan’s idle army and consulted with McDowell, Franklin, and some Cabinet officers on how it might be used. (Not yet aware that Porter had become Little Mac’s special confidant, Lincoln left him out.) On the morning of January 13, a wan and wary McClellan finally made an appearance, saying he had his own plans and his own schedule but declining to reveal them before so many people, lest details filter into the newspapers.

Secretary of War Cameron had been squeezed out of the Cabinet by then, replaced by Edwin Stanton, who had pretended to be McClellan’s best friend when the general seemed the foremost power in the land. McClellan initially greeted the appointment as a stroke of luck, but Stanton ended his first day as secretary in secret conference with McClellan’s worst foes among the Radicals, with whom he promptly allied himself.

A year later, McClellan and Porter would regret ever having heard Stanton’s name, and the new secretary quickly sealed his commitment to the Radicals by ordering the arrest of Charles Stone, the Union commander during the Ball’s Bluff debacle (see opposite). Stone’s efforts to impose discipline in his division had made him some enemies, and numerous officers, themselves of dubious repute, began impugning his loyalty. They fostered Radical hostility for him by pointing out that he returned runaway slaves to loyal owners, as required by law. Stone was imprisoned in New York Harbor early in February—on charges never formally specified—and the precedent had been set that political prejudice could be brought to bear to ruin a general.

The arrest cast a sudden pall over Porter’s demeanor. A staff lieutenant misunderstood that Porter feared some of the accusations might be true, but even Stone’s successor as division commander considered Stone perfectly innocent. Porter was troubled by Stanton, whom he and McClellan were already learning to mistrust. They recognized that Stone was being persecuted for his conservatism, and his failure to adopt Radical doctrine. They also knew that they might be next.