Mathew Brady ’s photograph gallery on Broadway in New York City welcomed a seemingly unbroken line of people. Once inside, the visitors entered an upstairs exhibition room where 95 small album cards were on display. Quietude pervaded the room as the onlookers gazed upon scenes never before photographed. Brady had described his new offering as “The Dead of Antietam.”

In October 1862, the art of photography had existed for less than three decades. The earliest processes involved daguerreotypes, ambrotypes or tintypes. A positive image was produced on a plate of silver-coated copper, glass or tin. None of the processes used a negative, and the images could not be reproduced.

In 1851 an Englishman developed a glass-plate negative, a process that allowed a photographer to mass-produce copies from a single negative. During the next few years, firms created three-dimensional stereoscopic photographs and cartes de visite, or visiting cards, of famous people and places. By the beginning of the Civil War, photographs in various forms had become common items in many American homes.

With the firing on Fort Sumter, American photographers faced a novel situation of historic importance. During the mid-1850s, cameramen had accompanied British, French and Russian armies during the Crimean War, taking photographs of fortifications, campsites and groups of officers and men. It was pioneering work, but the scenes depicted lacked the reality of a battlefield. The American Civil War, however, altered both the face of warfare and of war photography.

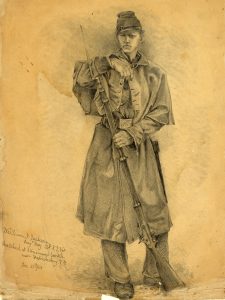

Like their European predecessors, American cameramen captured initially on glass the eager faces of volunteer soldiers, the martial postures of officers, tented camps, gun emplacements and landscapes scarred by earthworks. Brady sent employees to cover Union operations along the South Carolina coast, and the Peninsula, Seven Days’ and Cedar Mountain campaigns. But it was not until September 1862 and the Battle of Antietam that an unparalleled opportunity was offered to a pair of photographers.

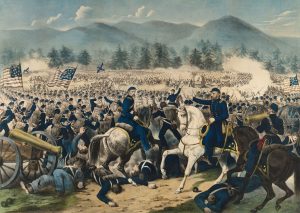

The engagement, fought on September 17, encompassed a savagery beyond the experience of even veteran troops. A participant likened the sound of the combat to “a great tumbling together of all heaven and earth.” Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac exacted a fearful price from each other—more than 4,000 killed or mortally wounded, and nearly 20,000 wounded or captured. Carnage engulfed the battlefield. It was, and still is, the bloodiest single day in American history.

On the day of the battle or the next Alexander Gardner and his assistant, James F. Gibson, employees of Brady, arrived in the rear of the Union army. During the night of September 18-19, Lee’s Confederates crossed the Potomac River into Virginia. With the Federals in control of the battlefield, Gardner and Gibson set out to record scenes never before captured by photographers.

The two men set up their camera at places that would resonate through history—Miller’s Cornfield, East and West Woods, Dunker Church, Bloody Lane and Burnside’s Bridge. Gardner and Gibson photographed the Pry house, McClellan’s headquarters; the stone-arched bridges across Antietam Creek; a Pennsylvania battery deployed for action; the ruins of Samuel Mumma’s farm; the dead horse of a Southern officer, looking as if it was asleep; a field hospital; and a burial detail. Antietam’s wreckage lay before them, and they captured it.

Most important, however, Gardner and Gibson traversed the battlefield before burial details had finished their tasks. For the first time in the immediate aftermath of an engagement, cameramen were able to make images of the corpses of slain men. They took photographs of dead Confederates, their bodies already bloated and darkened, on David Miller’s farm, along Hagerstown Turnpike, near West Woods, on the southern portion of the battlefield and in the Bloody Lane, where they appeared to be stacked like cordwood. The only photographs of Union dead were of Irish Brigade soldiers who had fought the Rebels at the Bloody Lane. The images evoked a stark reality and a haunting sadness.

In all, Gardner and Gibson produced 70 glass negatives. Gardner returned to Sharpsburg, Md., at the beginning of October and took another 25 photographs of the village and of Abraham Lincoln’s visit to the army. It was these 95 scenes that Brady placed on display and offered for sale in his gallery on Broadway.

A New York Times reporter looked at the album cards and wrote: “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it.” Brady’s “The Dead of Antietam,” wrought by Gardner and Gibson, was a turning point, a landmark in the history of war photography. Tragically for the country, their work and that of other combat photographers had only just begun.

Originally published in the August 2006 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.