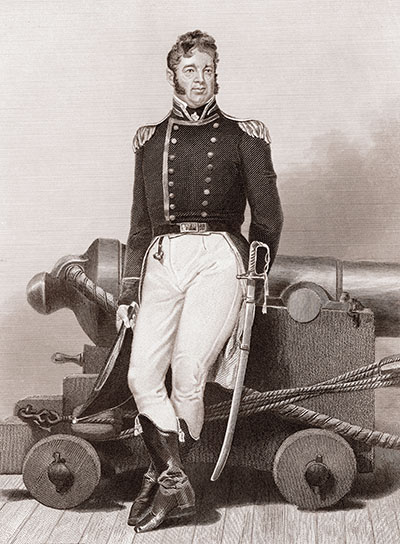

Stephen Decatur Jr. was 25 when he led the boarding party that destroyed the captured American frigate Philadelphia. (Orlando S. Lagman/U.S Naval Historical Center) (Orlando S. Lagman/U.S Naval Historical Center)

In recent years, piracy and hostage-taking off East Africa and the response by the

United States and allies have recalled the First Barbary War. During that 1801-05 conflict on the Mediterranean Sea off North Africa, President Thomas Jefferson, after many years of the United States paying ransoms rather than standing up to maritime brigands, forged a new national approach to foreign affairs. An electrifying episode in February 1804 reversed that pattern, crystallized Jefferson’s new policies, forcefully illustrated the maturation of American will and ferocity, and made a hero of a young U.S. Navy officer. In burning the U.S. Navy frigate Philadelphia, captured the year before and held by pirates in Tripoli Harbor, Stephen Decatur Jr. set a benchmark for audacity and martial enterprise.

The American shipping industry, which prospered in colonial times under the protection of the Royal Navy, entered the era of independence under French naval guardianship—until 1793. When the United States remained neutral in the French Revolution, France withdrew its protection at sea. Lacking a navy, the new nation now had to cope with ocean-borne outlaws who threatened American credibility and commerce. American merchant crews came under particular pressure along the Barbary Coast—today’s Morocco, Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria—at the time, home base for pirates sailing out of the Ottoman Empire’s North African holdings.

Piracy was a longstanding and persistent Mediterranean practice. Maritime outlaws, known as corsairs, had sailed there since the ninth century, taking ships and cargoes, and enslaving crews. The 1700s brought corsairs into contact with European pirates, who shared their techniques. Operating from ports like Algiers, Sale, Rabat, Tunis, and Tripoli, pirates aboard dhows, galleys, and captured European vessels—sometimes freebooting, sometimes allied with this European power or that—plundered at will.

Historically, Europeans had accepted as a cost of doing business the ransoming of crews, cargoes, and vessels, and the United States did the same. Short on cash and ill equipped to wage war, Presidents George Washington and John Adams authorized payments to free enslaved merchant crewmen.

In 1794, under Adams, Congress established the Department of the Navy and approved construction of six frigates for defense. Across the Atlantic, the hijackings, kidnappings, and ransom payments continued. As minister to France, Jefferson personally commissioned envoys to negotiate treaties and payoffs. In 1800, the United States paid tribute of $1 million—10 percent of annual government revenue—to Algiers alone.

Taking office as president in March 1801, Jefferson faced a populace weary of Americans being taken hostage and of paying dearly to free them. For their part, the pirates chafed at laggard American tribute. That May, the pasha of Tripoli, Yusuf Karamanli, angry at not being bought off more quickly, had his forces cut down the flagstaff at the American consulate. A waffling Jefferson authorized the Navy to send a squadron to the Barbary Coast, bearing gifts for various pashas but also orders to patrol the Mediterranean to protect American citizens and shipping. Gifts—and the display of naval power—mollified Morocco, Algiers, and Tunis. Tripoli stood alone.

Among that expedition’s five vessels was the 36-gun, 1,240-ton frigate Philadelphia, commissioned the year before at its namesake city, where in a week citizens had raised more than half the vessel’s $179,000 construction cost. The frigate’s first voyage, commanded by Captain Stephen Decatur Sr., was to the Caribbean, a scene of naval conflict with France. Under Captain William Bainbridge, the ship and its cohort then spent a year in the Mediterranean, after which Philadelphia returned stateside.

From a prison ashore, William Bainbridge, Philadelphia’s captain, sent intelligence to countrymen. (Getty Images) (Getty Images)

In February 1802, Jefferson, irate at continuing pir-acy, got Senate approval to use force against Tripoli. A new squadron commander, Commodore Edward Preble, negotiated with King Ferdinand IV of the Kingdom of Naples to base American ships at the Sicilian ports of Syracuse, Palermo, and Messina. Ferdinand also provided sailors, ship’s carpenters, and supplies. In Tripoli, the pasha seized the U.S. consulate and made it a prison.

Philadelphia again sailed to the Mediterranean, taking up a position off Tripoli. Chasing a pirate vessel on Halloween 1803, the frigate ran aground less than two miles from shore, near enough to come under fire from enemy land batteries and pirate vessels. Bainbridge and crew attempted to free, then to scuttle the beleaguered ship, but pirates overpowered the American sailors, imprisoning them at the former consulate.

Pirates salvaged and refitted Philadelphia, planning to rename the ship Gift of Allah and make it their fleet’s largest, most heavily armed element. The frigate loomed in Tripoli Harbor, a symbol of American disgrace, as Karamanli demanded the United States return Tripolitan ships and property the Americans had seized.

The rest of the American squadron remained on station nearby in the Mediterranean, periodically returning to Syracuse, 272 nautical miles and, under clear conditions, a five-day sail north. Constitution, commanded by Preble, blockaded Tripoli Harbor in tandem with Enterprise, a 12-gun schooner that had Lieutenant Stephen Decatur Jr., 25, at its helm. On December 23, 1803, the American warships stopped Mastico, a two-master departing Tripoli. Mastico’s crew carried questionable papers and had aboard items from Philadelphia. Claiming the would-be merchantman as a prize of war, the Americans armed the vessel and rechristened it Intrepid.

Preble and Decatur, each for his own reasons, itched to deal with Philadelphia. Preble, who would have preferred Bainbridge and crew fight to the death, thought Karamanli’s aggressiveness would encourage other Barbary states to break treaties with the Americans. Decatur, like his seafaring father a Philadelphian, wanted to free the vessel named for his hometown. Meanwhile, Preble and U.S. Consul General Tobias Lear were negotiating to obtain the crew’s release.

Preble and Decatur had unlikely assistance onshore. From captivity in the seized consulate, Bainbridge was gathering information. Using a spyglass he got from the Danish consul, who also carried his letters—the pasha believed free flow of prisoner mail encouraged ransom payments—Bainbridge monitored Philadelphia. In coded messages the Dane delivered to Preble, Bainbridge made clear the frigate was in no shape to sail. He also reported on other vessels and defenses in Tripoli Harbor.

Preble considered swooping into the harbor to seize, tow, and, once his men made repairs, sail Philadelphia out of enemy hands. But Intrepid was too small and Philadelphia too ragged. The better approach would be to burn the captured vessel.

The eager Decatur hatched a plan. He would lead a contingent of sappers including his brother James, all skilled at demolition, and U.S. Marines from the squadron’s ships. All were volunteers and, like their commander, ambitious as well as patriotic. Combat was a ticket not only to glory but also to promotion, and this mission promised plenty of fighting and no shortage of casualties.

Intrepid might have been too small to serve as a towboat—and leaky and rat-infested to boot—but it was the perfect vessel for a sneak attack. The Americans would disguise the former Mastico with short masts and triangular lateen sails to simulate a Tripolitan dhow. Flying Union Jacks, the little ship might fool pirates and guards into thinking it British. Crewmen did the makeover dockside at Syracuse.

“Board the frigate Philadelphia, burn her, and make your retreat good,” Preble told his force. “After the ship is well on fire, point two of the 18-pounders shotted [sic] down the main hatch and blow her bottom out.”

The 16-gun Syren, under Lieutenant Charles Stewart, accompanied Intrepid out of Syracuse on February 3. Aboard the disguised vessel were five Sicilian volunteers, including Salvador Catalano, an Arabic-speaking pilot who would do the talking once they entered Tripoli Harbor. Thomas McDonough, a Philadelphia crewman who had been on shore leave when his shipmates ran aground, would lead the team working below decks; he knew the frigate’s interior in the dark.

Decatur concocted a cover story: They were a British transport bound for Malta that had lost its anchors in a storm and needed to dock at Tripoli for repairs. To support the tale, the 85 or so men aboard dressed as Barbary Coast civilian sailors. To torch Philadelphia, the team brought fuses and candles made of spermaceti, a waxy, highly flammable substance found in sperm whale skulls. For additional flammability, the spermaceti candles rode in a bath of turpentine.

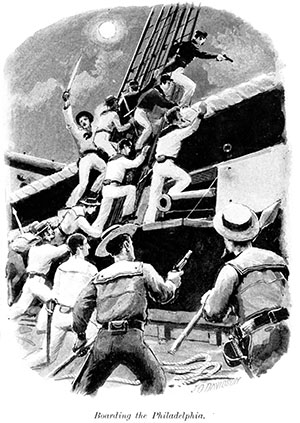

Decatur and his men scramble over Philadelphia’s rail. (U.S. Naval Historical Center) (U.S. Naval Historical Center)

Delayed by a gale en route, the force needed eight days to cross from Syracuse to Tripoli. Intrepid, built to carry 24 men, now had more than three times as many aboard. Heavy seas threatened to swamp the ship; seasickness slicked the decks with vomit. Decatur, however, was the picture of serene confidence. The gale subsided on February 12; three days later the ships linked up and Decatur ordered the attack for the night of February 16. The ships resumed course for Tripoli with Intrepid in the van and Syren in support.

The Americans were within sight of the African coast when the wind dropped, leaving the heavier Syren lagging in deeper water. Waiting for Syren would delay the attack and perhaps arouse suspicion. Decatur decided Intrepid would proceed alone. “The fewer the number, the greater the glory,” he told his men.

The bogus British vessel made Tripoli too early; unless he slowed down, Decatur would be sailing into an enemy harbor in broad daylight. Suddenly trimming sails would alarm watchmen ashore. Decatur had the crew tie ladders, spars, buckets, and other gear to a line and heave the impromptu sea anchor overboard to

retard their progress. Intrepid arrived at Tripoli Harbor after 7 p.m. beneath a waxing crescent moon. As if to endorse the ship’s disguise, personnel at the British consulate, seeing those false colors, raised their station’s flag to Intrepid. The impostor ship sailed along the coast toward Philadelphia, moored about a mile southwest of the consulate, in front of the pasha’s castle.

In his instructions, Decatur reminded Catalano, the Arabic speaker, which lies he was about to tell. The men of the boarding party, carrying only swords and pikes, would work in silence. As Intrepid neared Philadelphia, whose deck loomed 10 feet above the smaller vessel’s, Catalano called up to the frigate, spinning his yarn and asking if he and his mates could tie off Philadelphia for a night. Aboard the captured American frigate, the mood was suspicious. Someone spied Intrepid’s anchors. Others noticed knots of men lying on its deck, too many for a merchant ship of that size.

“Americanos!” a man shouted.

The closer Intrepid got, the more fraught the scene—until Decatur shouted “Board!” and leaped for chains dangling along the frigate’s hull. His men followed, some climbing over the rail, others shinnying through gun ports. Pirates panicked, scrambling overboard and screaming from the water to harbor watchmen; a few rowed for shore. About 20 Arabs stood and fought. All but one died—and he expired within hours. The attackers hacked the corpses to pieces and dumped them into the harbor. In 10 minutes, Decatur’s men, only one with wounds, and those minor, had secured Philadelphia.

The boarding party withdraws, having torched the Philadelphia, too badly damaged to save, to keep it from being used as a pirate warship. (Edward Moran/ U.S. Naval Historical Center) (Edward Moran/ U.S. Naval Historical Center)

There was no salvaging the ravaged frigate. Decatur instructed the below-decks team to get cracking. Men passed spermaceti candles up from Intrepid and positioned them around Philadelphia’s gunroom, berth deck, and cockpit storerooms. Walking the frigate’s deck, Decatur shouted “Fire!” into each open hatch. Flames licked planking and beams. Decatur gave the order to withdraw; he was the last to go, inches ahead of the fire. But the sappers’ luck did not hold. The night was dead calm, and the draft from the burning Philadelphia threatened to suck Intrepid into the blaze. Decatur had men drop rowboats tied to his little ship and put their backs into their business; the sailors towed Intrepid far enough away for a breeze to fill its sails.

Tripoli came alive. By the burning frigate’s glow, gunners at shore batteries and in Karamanli’s castle aimed for Intrepid; their rounds passed above the sails and between the masts but generally missed the mark. Soon the attackers were out of range and clear of the blazing Philadelphia. As they reached open water, Intrepid’s occupants gave three cheers.

By 11 p.m., Philadelphia’s last mast was collapsing. The mooring cables parted; the flaming hulk began to drift, visible to Syren, 40 miles north. The attackers’ ships met the next day. A two-day sail brought them near enough Syracuse that Decatur could signal Constitution, “Business, I have completed, that I was sent on.”

The business Decatur had completed proved a morale boost for his service and his country. “The most bold and daring act of the age,” declared British Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson. President Jefferson barely had time to seethe about Philadelphia’s capture when he was called upon to rejoice at its destruction. He made Decatur a captain, the Navy’s youngest ever, effective the date of the raid. Congress awarded him a ceremonial sword and voted his men two months’ pay as a bonus.

The United States was not done with pirates. A second, conclusive Battle of Tripoli Harbor would take place in August 1804, again featuring dramatic martial flourishes by Decatur. A painting of that engagement made decades later by artist Dennis Malone Carter would cement the young captain in the public’s imagination as the very model of an American fighting man. The shores of Tripoli—by way of the Battle of Derne in 1805—would

enter the American musical lexicon. There would be another Barbary War against Tripoli, Algiers, and Tunis, in which Decatur would reprise his leadership role—but the daring and deftness of the Philadelphia mission would make Stephen Decatur a household name. ✯

This story was originally published in the September/October 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.