A Vermont farm boy went to Vietnam as an aid worker and came home, in the eyes of the government, as one of the reasons the U.S. lost the war

Alongside members of the U.S. military, many aid workers, civilian government employees and contractors braved the risks of the Vietnam War and had their lives remade by the experience. One of those was Don Luce, who lived and worked in Vietnam from 1958 until his expulsion in 1971.

Luce was first a civilian aid worker, then a journalist; first a supporter of the American war effort, then a pacifist and war opponent. In 1970, he assisted a congressional delegation that investigated a South Vietnamese prison where captured Communist troops and others were kept in tiny cells, “tiger cages,” and often abused, even tortured. Luce’s sincerity and intimate knowledge of Vietnamese life—he is still fluent in Vietnamese, a notoriously difficult language to master—made his writings and speeches about Vietnam so effective that the last U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, Graham Martin, said Luce was one of the principal reasons the U.S. lost the war. Luce wound up spending much of his life focused on the people of Indochina.

The aid worker

Luce grew up on a 220-acre farm in East Calais, Vermont, a small village of some 200 people. He studied agriculture and received a master’s degree from Cornell University in 1958. Afterward, Luce joined International Voluntary Services, a nongovernmental organization that was the model for the Peace Corps. IVS’ biggest project at that time was in South Vietnam. There were no U.S. combat troops in the country then, just a small group of military advisers and intelligence operatives. Virtually all of the money for the IVS program in Vietnam came from the U.S. Agency for International Development, commonly known as USAID.

In 1958 Luce saw himself as a typical farm boy with no real interest in politics. He thought Dwight Eisenhower was a good president, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles was a great man and support for South Vietnam was important in saving America from communism. Luce arrived in South Vietnam on Nov. 8, 1958, and was sent to Ban Me Thuot, a provincial capital in the Central Highlands, largely populated with Catholics who fled Communist North Vietnam.

For the first month, he studied Vietnamese language with a 15-year-old boy, much of the instruction transmitted by playing the Vietnamese dice game called Horse. By Christmas Eve, Luce was able to appear at the local church and give a simple speech, which he describes as, “Hello, my name is Don. I am fine. I am glad to be in Vietnam. Thank you very much.” His language skills improved as he worked to introduce a higher-yielding strain of sweet potatoes to the peasant farmers.

Luce became associate country director for IVS in 1960 and moved to the organization’s compound near Tan Son Nhut Airport in Saigon. In 1961 he was promoted to IVS country director for Vietnam. During his time as director, the IVS team expanded its mission, adding teaching and community development to its original agriculture services. It also started accepting female volunteers. By 1967 the organization had 120 volunteers in Vietnam. Luce and some other IVS staffers were among the Americans most fluent in Vietnamese, giving them an intimate knowledge that eluded most U.S. policymakers and administrators concerned with Vietnam. Henry Cabot Lodge, a former U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, called the work of IVS “one of the success stories of American assistance in Vietnam.”

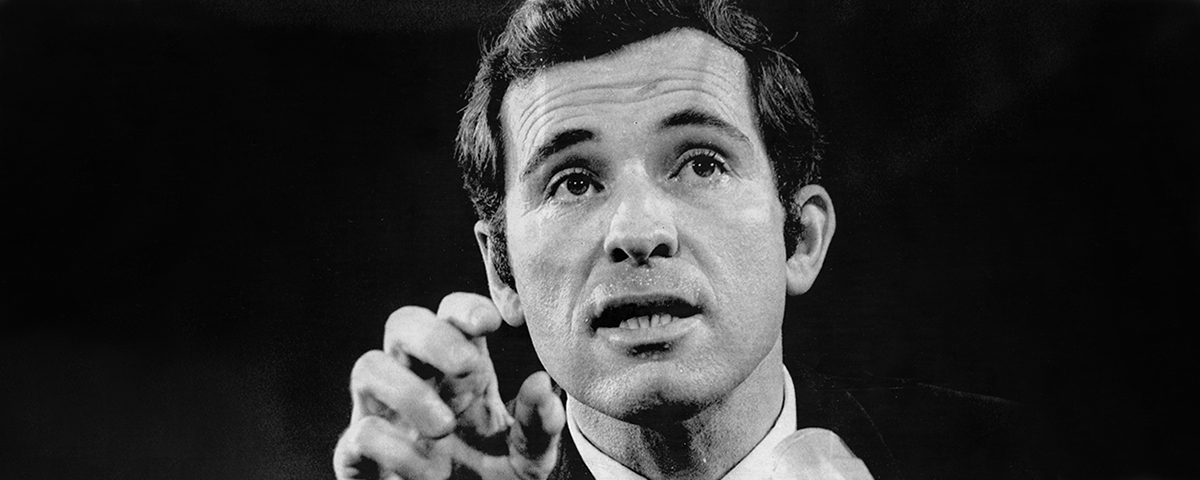

Luce was known for being soft-spoken and relying on a low-key, understated style of leadership. He worked constantly, was very determined and was “consumed with the Vietnamese cause,” in the words of one former volunteer. Even those who disagreed with his later anti-war turn thought him an effective leader.

Gloria Emerson, The New York Times’ Vietnam correspondent for three years, described Luce as “a gentle and austere man, born without a temper, almost unable to return anger.” A 1972 report from IVS to USAID later described him this way: “Though short of administrative skill, the knowledge of Vietnam which Luce acquired, and his competence in dealing with government officials, gave this [director] prestige which was respected and acknowledged by the volunteers who worked under his authority.”

When conflict arose, Luce generally avoided personal attacks to focus on institutional or policy failures and persuading people to make changes. Asked about his calm approach, Luce quotes a line from the poetry of the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, “Remember, brother, remember / Man is not our enemy.”

The IVS volunteers in Vietnam were idealistic, but working with peasants in the villages, they saw firsthand the debilitating effects of bureaucratic inertia, corruption, discrimination against ethnic minorities and the crackdown on Buddhist monks and other dissidents. A Buddhist monk who had befriended IVS volunteers in Ban Me Thout died in a suspicious accident — just after he refused to teach a propaganda course for the government. One IVS volunteer narrowly avoided injury when South Vietnamese tanks fired into a crowd of peacefully protesting Buddhists in Hue. An IVS jeep was shot up.

Luce began having doubts about the efficacy of the American effort. Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara’s speech to a large crowd of Saigon civil servants and government supporters in 1964 seemed to symbolize the problem. Luce was there with some university students. At the end of McNamara’s remarks in English, the defense secretary raised his arms to shout in Vietnamese, “Viet Nam muon nam,” intending to say “Vietnam will win.” He was apparently unaware that Vietnamese is a tonal language in which words have very different meanings depending on the accent and inflection. What McNamara had actually said to the bemused crowd— astute enough to nevertheless cheer loudly—was: “The southern duck wants to lie down.”

As the U.S. military effort in Vietnam ratcheted up in 1965, IVS found itself being dragged into the conflict. One volunteer, Peter M. Hunting, was killed in what appeared to be a guerrilla ambush in late 1965. Luce had been a good friend and was deeply affected by his death. Max Sinkler was hit by a Korean military truck and died in 1966. Other IVS volunteers came under fire when traveling. By early 1966 most of them were living in provincial capitals rather than in the villages.

In the meantime, American leaders wanted closer coordination between IVS and U.S. government agencies, which had the effect of publicly tying the organization to USAID and the CIA, thus alienating the Vietnamese that IVS worked with.

Luce and other IVS staffers started to openly question the merits of their work. As they saw it, the military strategy and tactics, as well as the government programs for civilians, were destroying the fabric of village life. They were leading to hunger, forced migration, prostitution and alienation from the South Vietnamese government. Sometime between 1965 and 1967—Luce doesn’t remember any single defining moment—the destructiveness and futility of the war turned him into a pacifist.

By 1967 Luce and others decided their work with IVS could not really help the Vietnamese in the midst of the American war effort. At a big staff meeting over the July 4 weekend in 1967, Luce and three other senior IVS staff members announced they were resigning.

A group of volunteers drafted a letter to President Lyndon B. Johnson expressing their dismay with the war; 49 volunteers signed it. They agreed to each chip in $5 toward the cost of publishing the letter as a full-page ad in The New York Times. When they learned the price of an ad—many thousands of dollars—the IVS workers, each making $75 a month, realized they could not afford it. But a Times reporter wrote a story about their actions and quoted the letter, making a far larger impact than an ad would have.

The letter to Johnson, released in September 1967, caused a minor uproar: Young, idealistic and brave volunteers in Vietnam were turning against the war. Vice President Hubert Humphrey later called the IVS resignations “one of the greatest disservices to the American effort in Vietnam,” and even some IVS staffers in Vietnam, who had opposed the letter, continued to back U.S. policy in Vietnam. On the other hand, many Vietnamese were supportive of the letter. “We thought you were CIA, but now we know differently,” one Vietnamese acquaintance said.

After the Communists’ 1968 Tet Offensive, a series of attacks that struck towns and military bases throughout South Vietnam, IVS decided to scale down its operations in Vietnam for security reasons. Meanwhile, the deeply divided views of the volunteers made IVS’ relationship with both the U.S. and South Vietnamese governments more fractious. In 1971, the Saigon government terminated IVS’ contract, and the volunteers all left.

Luce returned to the U.S. in September 1967 and spent several months at Cornell as a research associate. He also gave speeches around the country on his misgivings about the war. Luce and former IVS team leader John Sommer used that year to write a book, Vietnam: The Unheard Voices, which described the destruction that the war was causing.

The book, published in 1969 by Cornell University Press, had an impact because it was written by Americans who spoke Vietnamese and knew the country’s culture well after spending long days and weeks with peasants, slum dwellers, students and families who had become refugees inside their own country after fleeing the fighting or being displaced by government decrees. “We were trying to find a way to give the Vietnamese a voice in the debate,” Luce said in an interview.

American policy was crafted by leaders who could not communicate with or understand the people they were supposedly helping, Luce and Sommer stated in their book and then explained the consequences. “Because American understanding of the people has been so limited, the tactics devised to assist them have been either ineffective or counterproductive. They have served to create more Viet Cong than they have destroyed.”

Unheard Voices was a plea on behalf of the Vietnamese who were not wealthy or powerful and suffered the brunt of the war and its consequences.

The journalist-advocate

In mid-1968 Luce returned to South Vietnam, this time funded by the World Council of Churches to ostensibly write a report dealing with reconstruction of Vietnam after the war, which some in 1968 apparently thought would end sooner than it did. Most of his efforts, however, went into freelance journalism.

Luce worked with Vietnamese friends and acquaintances to uncover stories about prisons, poverty, urban slums and camps that housed people left homeless by the fighting. He also looked at what voluntary agencies were doing.

Luce generally shunned a byline and focused on providing story ideas, verifiable information and reliable witnesses to established journalists like Emerson of the Times, Morley Safer of CBS News, Carl Robinson of The Associated Press and Beth Pond of The Christian Science Monitor so important stories would find their way into credible outlets.

Luce lived in a top-floor apartment of a seven-floor walk-up on Avenue Louis Pasteur in the heart of Saigon. The floors below him housed a brothel catering to American soldiers. Luce used to spend time in conversation with the sex workers. He saw them as similar in many ways to the political prisoners, being degraded and held hostage by the war. Luce’s modest apartment had one major convenience: a balcony that would provide visiting anti-government activists with access to a fire escape that enabled them to safely avoid the Saigon police.

In spring 1969 Sommer somehow wrangled a meeting with Henry Kissinger, the national security adviser to newly inaugurated President Richard Nixon. Luce, in the U.S. briefly, and Sommer met Kissinger in his White House basement office, where the president’s aide confidently assured them that he and Nixon wanted to end the war, the war had to be ended and they had a plan. Luce expressed skepticism, while Sommer was inclined to believe the assurances. “And, of course,” Sommer now says, “Don was right.”

Luce helped organize a project to get members of Congress to lobby the American Embassy and U.S. government for release of political prisoners held by Saigon. At the urging of Saigon student leaders opposed to the South Vietnamese war effort, he began visiting a prison warden who, after receiving hospitality gifts of Johnny Walker Scotch whisky and cartons of Marlboro cigarettes, became amenable to releasing student dissidents from their cells.

In 1970, when three American journalists were captured by either North Vietnamese or Viet Cong forces, Luce was invited to chat with unidentified men at the Brodard ice cream parlor, where he vouched for the honesty and integrity of the reporters. The journalists were shortly released; Luce hopes he had been helpful but was never quite sure how important his efforts had been.

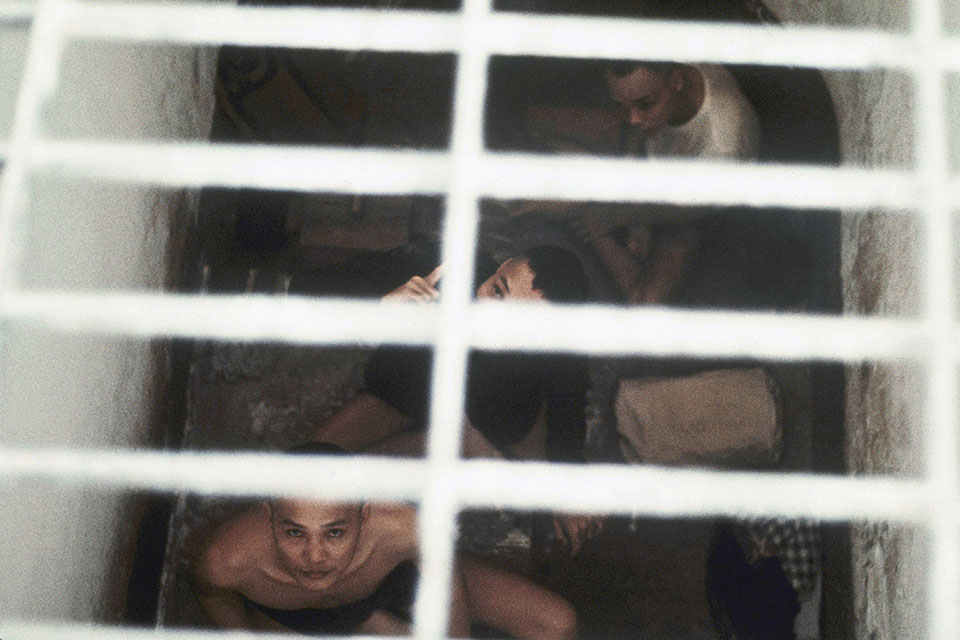

Undoubtedly, Luce is principally famous—or infamous, depending on one’s views—for his role in uncovering the tiger-cage cells. In 1970 South Vietnam’s prison on Con Son, the main island of the Con Dao archipelago, about 60 miles off of the coast, housed almost 10,000 prisoners. Some 500 were political prisoners kept in small cages in a walled-off section.

Luce had heard about the tiger cages from former prisoners and relayed what he knew to Tom Harkin, a staff aide for a delegation of 10 congressmen visiting Vietnam in July 1970. Harkin (an Iowan who later became a member of the U.S. House and then a senator) arranged to have two of the congressmen travel to Con Son and try to find the secret tiger cages—cages the South Vietnamese and U.S. governments said no longer existed. Luce accompanied them as an interpreter.

The delegation succeeded in a dramatic fashion, bringing out a firsthand account and photographs of the miserable conditions. The tiger-cage story, appearing shortly after the U.S. invasion of Cambodia in April 1970 and campus demonstrations across America in May, received widespread international coverage that frequently included quotes from Luce. The South Vietnamese government soon announced that the tiger-cage unit was being demolished and treatment of prisoners upgraded.

The U.S. and South Vietnamese governments took a dim view of Luce’s activities. In October, the Saigon government informed Luce that his press card would be revoked. In January 1971, the U.S. Embassy suspended Luce’s mail privileges and started returning his mail to senders. Luce’s landlady, happy to run a large brothel but nervous about tenants who criticized the government, evicted him.

Luce, who took an apartment in Tran Hung Dao Street, was followed while walking around the city. A friend in Saigon military intelligence warned: “Don, you’ve got to be more careful. They’re out to get you.” One evening, Luce returned to his apartment to find his front door lying on the ground and his possessions scattered on the floor. However, his bed was neatly made, and since Luce never made his bed, he was suspicious. He carefully pulled back the covers to find tied in the sheets a snake that he identified as a “two-step” because its poisonous bite was widely believed to kill you before you could take more than two steps.

On April 17, 1971, Luce received an official letter expelling him from the country and requiring him to leave no later than May 16. On May 5, he flew home.

The activist

Back in the U.S., Luce became a full-time anti-war activist. He and other IVS veterans created the Indochina Mobile Education Project, affiliated with the Indochina Resource Center and Project Air War. The three nonprofits operated from a small four-story office building in Washington. (I first met Luce in the fall of 1972, a year out of college, while I was working as a researcher at the Indochina Resource Center and living in a group house with former IVS volunteers.)

Luce was rarely in Washington. He and others toured the country in a minivan to talk about the war and its terrible effects on both Vietnam and America. They hit almost every state and spent a lot of time in small towns. The main event always featured a Vietnamese dinner that Don and his team would cook, usually thit ga (stewed chicken). One colleague remembers Luce as a persuasive speaker, quiet but firm, speaking about values, not ideology. Luce would say that he was just a farm boy and proceed from there.

The war ended with the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, and the evacuation of U.S. personnel. A subcommittee of the House Committee on International Relations conducted hearings on the evacuation, and Martin, the ambassador during those final days, testified on Jan. 27, 1976. He assured Congress that the collapse of the South Vietnamese government had nothing to do with the policies of Saigon or Washington but was caused “by one of the best propaganda and pressure organizations the world has ever seen,” largely organized by the Indochina Resource Center and “the multi-faceted activities of Mr. Don Luce.”

Postwar

Luce stayed involved with Asia, working for aid organizations, leading study groups to Vietnam and providing money for programs supporting HIV awareness. His activities included arranging for Vietnam Prime Minister Pham Van Dong to be interviewed for Penthouse magazine and, in 1979, joining the murderous Pol Pot for chicken dinner while accompanying a television crew to a Khmer Rouge hideout in northwestern Cambodia.

Luce, who turned 82 this past September, currently lives in Niagara Falls, New York, and works as an administrator for Community Missions, a soup kitchen and homeless shelter. In his 30s and 40s, Luce says, he tried to change big national policies, but “now I try to concentrate on helping a few people have an easier life.” He looks at life “from a Niagara Falls soup kitchen perspective.” Luce picks up food donations from supermarkets for the soup kitchen, raises money to support the homeless shelter and spends time at home listening to music with his longtime partner, Dr. Mark Bonacci.

There are many Americans, particularly Vietnam veterans, who vigorously disagree with Luce’s perspective about U.S. policy in Vietnam and with his activities during the war. But Luce came by his beliefs honestly through his experience in working with Vietnamese peasants and students during the war. He lived his beliefs in the face of government threats and attacks on his integrity—and his life—and never lost his affection for the people of Vietnam.

Ted Lieverman is a freelance documentary photographer and writer based in Philadelphia. His website is www.tmlphotojournal.com. He also writes for www.consortiumnews.com.