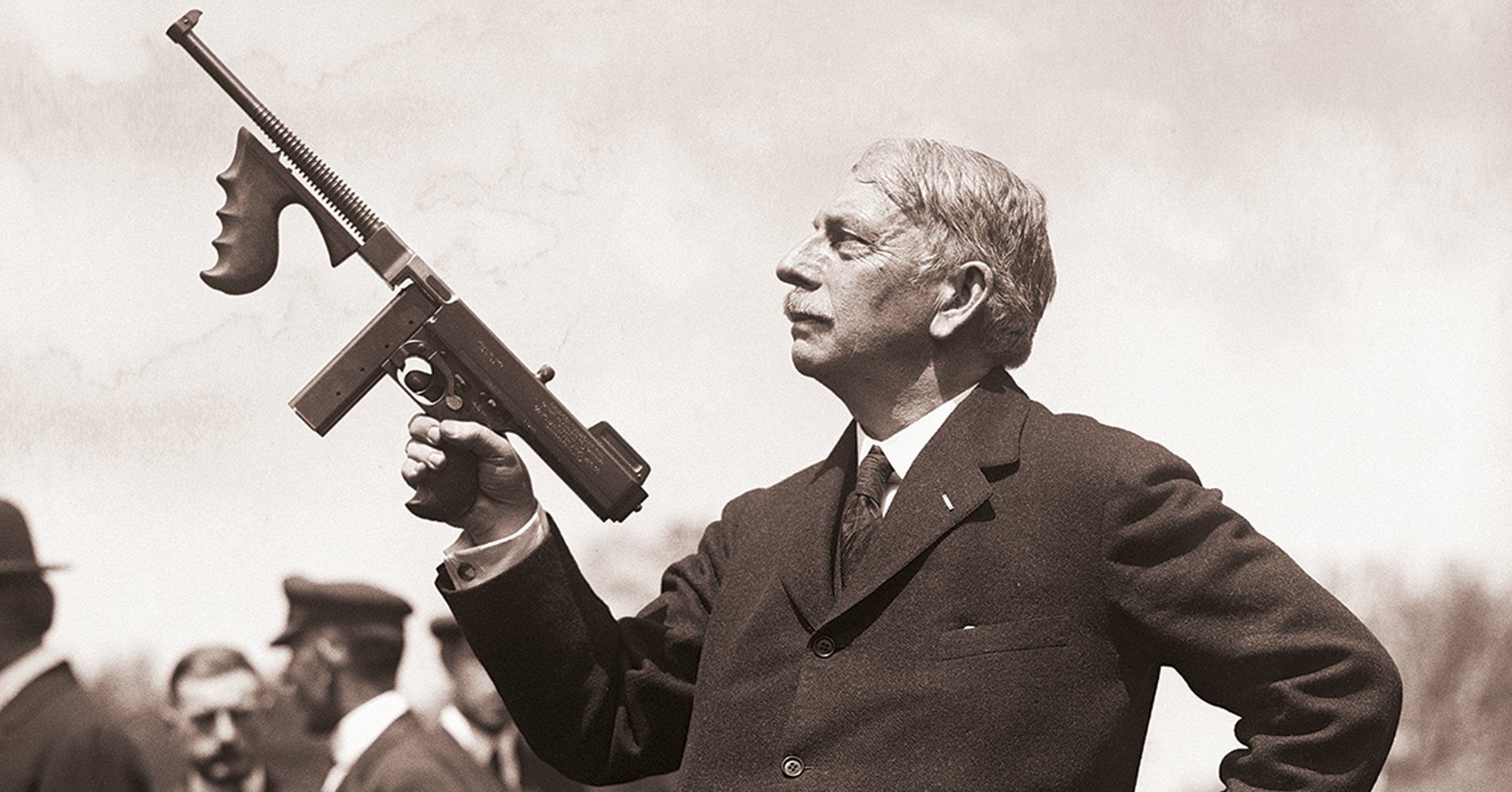

Brigadier General John T. Thompson was the inventor of the Thompson submachine gun, the iconic “Tommy gun” of so many gangster movies. Even people who are not historians, history buffs or gun enthusiasts give the Thompson recognition only a select few weapons earn. The Colt Model 1911, the Luger, the Uzi—the list is short.

One memorable namesake invention would be a fine legacy for most people, but in Thompson’s case it is a shame, because so much is left out. From ordnance officer during the Spanish-American War to developer of one of the most widely used rifle rounds in the world, Thompson was a giant in the manufacture of modern American military firearms. Only John Moses Browning had a hand in making more U.S. Army infantry weapons than Thompson.

Born on New Year’s Eve 1860, John Taliaferro Thompson was the son of Army Lt. Col. James Thompson. Despite a childhood spent moving from post to post, John decided to follow in his father’s footsteps. He graduated 11th in West Point’s Class of 1882 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery. After attending engineering and artillery schools, he joined the Ordnance Department in 1890, earning a reputation as an intelligent and steady officer. At the April 1898 onset of the Spanish-American War he was a gunnery and ordnance instructor at West Point, but the War Department promoted him to lieutenant colonel of volunteers and appointed him chief ordnance officer for Maj. Gen. William Rufus “Pecos Bill” Shafter, commanding the V Corps landing in Cuba. To his disappointment Thompson was instead ordered to Tampa, Fla., to sort out the enormous tangle of materiel being shipped there from across the nation. He was the man for the job. Over the course of the conflict he arranged for more than 18,000 tons of munitions to be shipped to Cuba.

While Thompson was plowing through that herculean task, Lt. John Henry Parker, who’d been training infantrymen on machine guns, brought to his attention more than a dozen crates of Gatling guns idling on the docks. These early hand-cranked weapons were not on the manifest of items urgently needed in Cuba, but on his own authority Thompson resolved to ship them immediately. He also sent Parker with a letter recommending Shafter appoint him to set up a Gatling gun attachment. The Gatlings saved the day at the July 1 Battle of San Juan Heights, allowing Col. Theodore Roosevelt, his Rough Riders and fellow American soldiers to clear Kettle Hill and force the Spanish off adjacent San Juan Hill. For his wartime accomplishments 27-year-old Thompson was promoted to colonel of volunteers—the Army’s youngest at the time.

As veterans returned stateside, Thompson debriefed them about the weapons they’d used, and it became clear the Krag-Jorgensen rifles issued by the Army were inferior to the Mauser M1893 used by Spanish troops. On reviewing the findings, Chief of Ordnance Brig. Gen. William Crozier promoted Thompson to regular captain and assigned him to the Springfield Armory to come up with a solution.

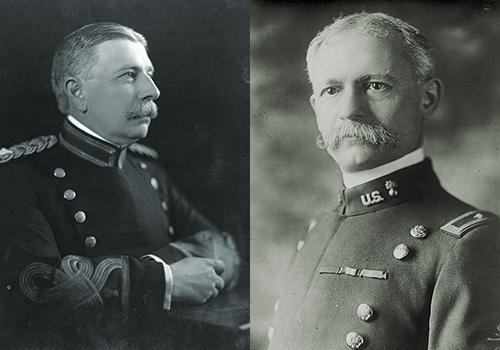

When considering Thompson’s qualifications, it is instructive to know what Crozier thought about ordnance officers in general:

The designing and constructing ordnance officer must be a mechanical engineer.…The ordnance officer’s knowledge of engineering subjects must not be merely that of the liberally educated man…but that of the expert with details at his finger ends, and he must have a specially sound mastery of principles, since he must oftentimes deduce the methods of their application to his art without the aid of the many handbooks and practical treatises which are available in the civil practice of the engineering profession.

Crozier himself had patented a number of inventions used by the Army before becoming its chief of ordnance. As may be expected, Thompson did not make all the decisions by himself. Usually he was the lone ordnance officer on a board composed variously of line officers, civilian representatives of industry, and military and private designers. In the end no gun or cartridge was adopted without Crozier’s approval.

In the end no gun or cartridge was adopted without Crozier’s approval. Then why credit Thompson with developing the weapons and ammunition listed herein?

Then why credit Thompson with developing the weapons and ammunition listed herein? Thompson was Crozier’s representative, and no decisions were made without his sign-off. If the design failed in any way, there was no doubt who would get the blame. Similarly, he deserves credit for having contributed to so many successes.

With regard to the Krag, the first step Thompson and the ordnance board took was to develop a high-velocity round, a time-consuming effort in itself. But the breech mechanism was not robust enough for the more powerful cartridge. A new rifle was called for.

After much reflection and hesitation, the board decided to pattern a rifle after the Mauser design. The decision-makers were in good company, as in the forthcoming world wars virtually every participant army would rely on a rifle owing something to the classic Mauser. Reinventing the wheel takes time and money, and the Mauser was a proven winner, so that’s where Thompson started. His design, however, proved too obvious a copy, and the federal government ultimately had to pay a quarter million dollars in royalties to Mauser for copyright violations—not just for the new rifle but also for the ammunition clip and bullet. Unlike many government purchases, it turned out to be money well spent.

The resulting weapon, the M1903 Springfield, was the Army’s standard-issue infantry rifle until 1936, though it was partially supplanted in 1917–18 by an Enfield design midwifed by Thompson. Crozier was impressed with the result. “The standard rifle of the American service, popularly known as the Springfield, is believed to have no superior,” he crowed after the war.

One wonders what the designer of the Mauser would have thought of that.

Hyperbole aside, leading the design team for the M1903 had been an impressive notch in Thompson’s belt. That said, the cartridge he helped develop for the M1903 would have an even more lasting and widespread impact.

The Krag’s smokeless cartridge was underpowered, so Thompson supervised the design and production of the improved, roundnose .30-03, which debuted in 1903. Even as it was being issued, however, European armies were switching to more aerodynamically efficient pointed “spitzer” bullets. The U.S. Army had to follow suit and once again copied a Mauser design a little too closely. Complicating matters further, the new type of round necessitated modification of the M1903, with a shorter barrel at the breech and a resized chamber. Meanwhile, work continued on an acceptable cartridge.

Approved in 1906, that cartridge was the .30-06, commonly called the “thirty aught-six.” The round and its derivatives may constitute the most widely produced ammunition ever made. Despite the introduction of a copper jacket, further aerodynamic refinement in 1926 and multiple variations in propellant composition, it essentially remains the same round to which Thompson gave his stamp of approval.

With the M1903 Springfield, the “thirty aught-six” cartridge, the Colt M1911 and the .45 ACP round, Thompson had set the Army on the path to having modern, hard-hitting small arms that would serve soldiers well for years to come

Thompson was not yet done producing military classics. An unexpected outcome of the Spanish-American War was the acquisition of the Philippines, followed by a major uprising against U.S. rule of those far-off islands. In 1892 the Army had switched from the .45-caliber M1873 Colt revolver to the .38-caliber Colt M1892, but combat experience in the Philippines showed that rounds from the latter were too light to stop a charging opponent, particularly if that opponent were a suicidal Moro warrior hopped up on painkilling drugs. As a stopgap the Army dusted off its surplus .45s for distribution to the troops. Crozier then tasked his right-hand man, Thompson, with finding a viable replacement.

For this assignment Thompson’s research took an unusual turn. In 1904 he and Medical Corps Maj. Louis La Garde, a specialist in wound ballistics, traveled to Chicago. There they visited a cattle stockyard and spent two days shooting dozens of steers with assorted weapons and calibers of ammunition to establish which was most effective. They also fired rounds into human cadavers. Though grotesque by present-day standards, the tests were conducted with the intention of saving American lives on the battlefield. As a starting point Thompson and La Garde decided the new sidearm would have to be .45-caliber and hold at least six cartridges. An impressed Crozier promoted Thompson to regular major and placed him in charge of a new Small Arms Division responsible for selecting a pistol.

Armed with a mandate and no war on the horizon, Thompson spent the next six years working with such known designers and manufacturers as Colt, Savage and Deutsche Waffen- und Munitionsfabriken (employer of one Georg Johann Luger). Working for Colt at the time was John Moses Browning, whose resume of brilliant pistol, rifle, shotgun, machine gun and ammunition designs gave him an obvious edge over his competitors.

The contest came down to a 1910 endurance test between Browning’s Colt design and one from Savage. In the end the Savage suffered dozens of breakdowns, the Colt none at all. The next spring the Army adopted Browning’s semiautomatic pistol as the Colt M1911. It would serve as the standard Army sidearm for 75 years—a record unparalleled since the flintlock era.

At the same time Browning designed a .45-caliber rimless cartridge for the M1911. Though it started out as a .41-caliber round for a cavalry gun, troopers wanted more stopping power, and he upped the cartridge to .45. With minor modifications, the Army adopted the .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) in August 1911. Browning had designed it as a low-velocity round, as high-velocity bullets tend to zip right through their unfortunate targets, while low-velocity rounds are likely to cavitate when they hit and cause more damage. The .45 ACP was later used in both the Thompson submachine gun and the M3 “Grease Gun” intended to replace the Tommy.

With the M1903 Springfield, the “thirty aught-six” cartridge, the Colt M1911 and the .45 ACP round, Thompson had set the Army on the path to having modern, hard-hitting small arms that would serve soldiers well for years to come. By 1913 he’d risen to the rank of colonel.

And then he retired.

The Thompson submachine gun was the first and only gun he designed outside the Ordnance Department, but he used the same techniques he had on all his other projects, and it enjoyed the same success

By 1914 Thompson had been a soldier for 32 years. He decided to hang up his sword and land a bigger paycheck, though with the onset of World War I he felt compelled to use his technical knowledge and experience to help defeat the Central Powers. As long as his country sat out the war, the best way he could participate was outside the Army. He was in luck. Remington Arms hired him to be chief engineer at an enormous new factory they were building in Eddystone, Penn., to manufacture .303-caliber Enfield rifles for the British. The Eddystone Arsenal was the largest factory in the wartime United States, turning out nearly 2 million rifles between 1915 and ’19.

Thompson did not make it to 1919 with Remington. On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany, and with that Ordnance Chief Crozier recalled his most trusted aide to uniform and gave him a task for which he was uniquely qualified—jump-starting rifle production. “I called Colonel Thompson back into active service,” Crozier recalled, “and placed him in charge of small arms and small arms ammunition, and had the benefit of his expert and especially well-informed advice.”

Thompson had a couple of options. He could simply ramp up production of the M1903 by increasing capacity at existing factories and building huge new facilities like he had for the .303 Enfield. Unfortunately, there was nothing simple about it. The arsenals already producing the M1903 would never be able to keep up with demand, while new factories are expensive and take time. There would be a minimum six-month lag before production could start, and none would reach full capacity for 18 months.

On the other hand, the largest rifle factory in the world was already cranking out guns for the British in the United States by the trainload. The Army could just adopt the .303 Enfield. But the problem was the .303 was just that. While the Army had millions of rounds of .30-06 in stock, it had no .303. As a final blow, by universal consensus the .303 was not as good a round as the .30-06. It was weaker, and the rimmed cartridge had to be carefully loaded into the Enfield’s internal box magazine, the rims overlapping in the right sequence to avoid potential jams. The British had been about to switch to a rimless cartridge in 1914, but then the war broke out and forced them to crank out the rifle and ammunition they had in hand. “The ammunition which it fired was out of the question for us,” Assistant Secretary of War Benedict Crowell said. “Not only was it inferior, but since we expected to continue to build the Springfields at the government arsenals, we should, if we adopted the Enfield as it was, be forced to produce two sizes of rifle ammunition.”

Thompson had been on the team that designed and built the M1903, and he’d been the engineer in charge of manufacturing hundreds of thousands of Enfields. Surely, he’d know which course was best? He did. He wanted neither.

In his opinion both rifles were all but obsolete. The simplest solution was to update the Enfield and rechamber it to use the .30-06. Best of all, he told Crozier, he could have it ready for production in four months. He did.

Thus the M1917 Enfield was born. Within a year Eddystone and other factories were turning out 10,000 M1917s a month. Thompson was promoted to brigadier general and was later awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. “The decision to modify the Enfield was one of the great decisions of the executive prosecution of the war,” Crowell recalled, “all honor to the men who made it.”

Interestingly, the Army never adopted the M1917 as its standard-issue rifle. The M1903 carried on in that capacity until replaced in 1936 by another outstanding design, the M1 Garand—the first Army rifle since 1903 not to have Thompson’s fingerprints all over it. As the Garand only partially replaced the M1903 at the start of World War II, Springfield ramped up production of the latter out of necessity until enough Garands were available. Both the M1903 and M1917 soldiered on in steadily diminishing numbers through war’s end, the M1903 lingering even longer as a sniper rifle.

Ironically, the final resting place of most M1917 Enfields was Great Britain. Before the United States was jolted into World War II, the Army had geared up to make millions of M1 Garands, believing they wouldn’t need all those old bolt-action rifles in surplus. Army brass sold many such M1917s to the British during their 1940 invasion scare. More than 700,000 were ultimately issued to its Home Guard, the citizen militia fondly recalled year’s later in the BBC sitcom Dad’s Army. Unfortunately, the U.S. version of the rifle caused the British the same kind of headaches adoption of the .303 Enfield would have caused Americans. They were forced to allot scarce money and even scarcer shipping space to import millions of .03-06 rounds from across the pond. At least you could load an M1917 in the dark without setting yourself up for a jam.

The M1917 is not just a historical footnote. “Sportsterized” surplus rifles proved so popular among hunters and target shooters that Remington rolled out more than 25,000 Model 30 civilian versions. These, along with surplus military models sold to the general public, are still used for hunting and target shooting. Original M1903s are being sold (and some fired) as we speak. It is the most revered and collected U.S. Army rifle ever made.

So it should be for all of Tommy’s other guns, as well as the ammunition he designed for them. By the end of World War I Thompson was already deep into the process that would result in his “Trench Broom” being produced, first in trickles, then by the hundreds of thousands as the world went to war once again. The Thompson submachine gun was the first and only gun he’d designed outside the Ordnance Department, but he used the same techniques he had on all his other projects, and it enjoyed the same success. But while the famed Tommy gun may overshadow John Thompson’s many other achievements, they are neither gone nor forgotten. MH

Michael O’Brien is a graduate of the University of Kansas whose lifelong interest in history was sparked by his Army officer father’s extensive library on the subject. For further reading he recommends Tommy Gun: How General Thompson’s Submachine Gun Wrote History, by Bill Yenne; The Thompson Submachine Gun: From Prohibition Chicago to World War II, by Martin Pegler; and Ordnance and the World War, by Gen. William A. Crozier.