The cultured French town of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, is steeped in history—the more recent of which residents would rather forget

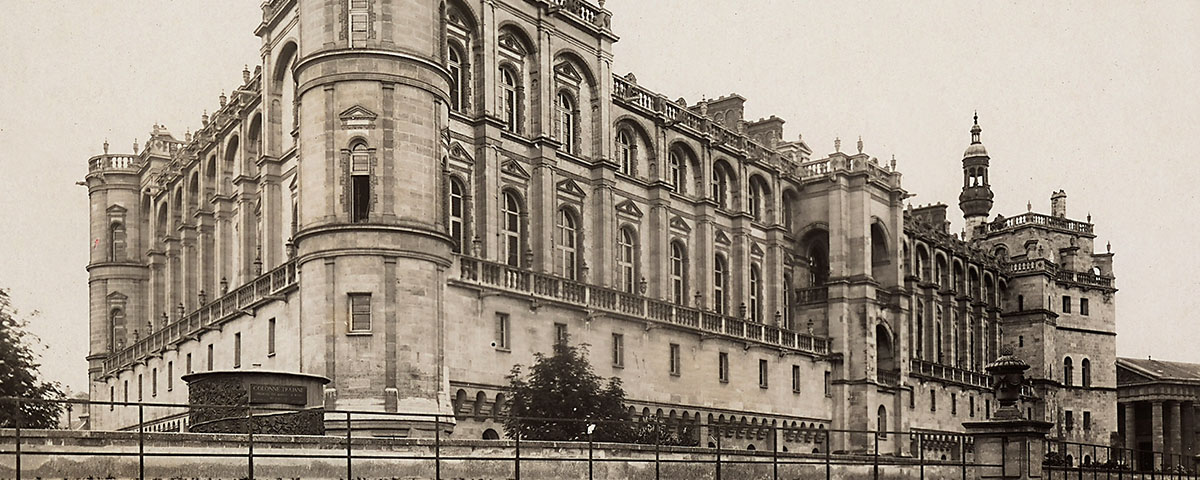

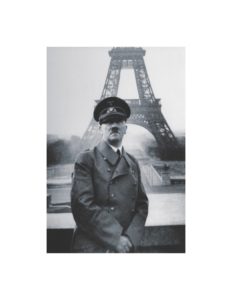

Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, takes pride in its centuries-old château, exclusive neighborhoods and top-notch schools. As the birthplace of King Louis XIV (in the château), the hunting grounds of Henri IV and the residence of other European nobles, it styles itself a “royal town.” During the 1940–44 German occupation of France its strategic location on a plateau a dozen miles west of central Paris made Saint-Germain the ideal location for the Oberbefehlshaber West—the Wehrmacht’s supreme commander on the Western Front. The town’s 43,000 residents don’t discuss that period of its history so much.

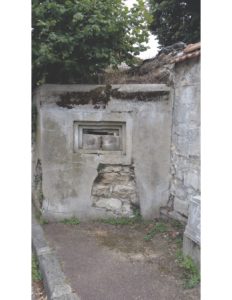

The Germans left the otherwise charming town a problematic legacy: a network of 22 reinforced concrete fortifications, most of which remain all too visible. The largest bunker comprises 10,000 square feet over three stories, mostly underground. One 1,400-square-feet bunker squats right beside the château, two occupy public school grounds and another is smack in the middle of a military housing complex. Authorities have deemed these relics unsafe for public use but too expensive to destroy. While a town may readily remove unwanted statues, what can it do with indestructible bunkers? The answer, for Saint-Germain, is nothing.

“In a city with the historical and cultural richness of Saint-Germain, there are more interesting things to showcase,” Mayor Arnaud Péricard explains. “It was not a happy page of our history. It was traumatic for the residents.”

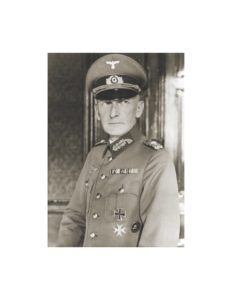

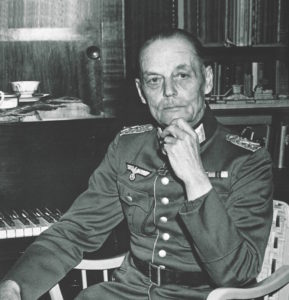

Following the 1940 establishment of OB West, as the Germans referred to it, Field Marshal Gerd von Rund-

stedt arrived in Saint-Germain to lead the command, answering directly to Adolf Hitler for the direction of some two-dozen army divisions. OB West’s mission soon centered on setting up defenses, both their physical construction and the deployment of resources to them.

Across France’s northern occupation zone in 1941 an estimated 300,000 German troops lived among some 25 million French civilians. Between 10,000 and 15,000 German soldiers billeted in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, whose wartime population hovered at about 20,000 people, according to François Boulet, local historian and author of the French-language History Lesson of France: Saint-Germain-en-Laye, From National Antiquities to an International City. No other town in France had such a high concentration of occupation troops. In Saint-Germain the officers took over private mansions, such as that owned by Louis Louis-Dreyfus, director of the Louis Dreyfus Group of commodity distributors (and great-grandfather of American actress Julia Louis-Dreyfus), who had fled the occupation. Enlisted men were housed in school buildings or with local families.

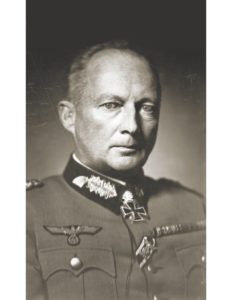

As Hitler mulled the invasion of the Soviet Union in the spring of 1941, he transferred Rundstedt to the East and brought in Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben to head OB West. Witzleben either fell ill or out of favor in March 1942, however, and Hitler returned Rundstedt to Saint-Germain. His arrival came on the heels of a devastating air raid by Royal Air Force bombers on the western suburbs of Paris that severely damaged the Renault plant at Boulogne-Billancourt and the Ford plant at Poissy—both were producing vehicles for the German army—as well as homes in Saint-Germain. Le Courier, the local newspaper, reported the deaths of 46 civilians in the strike. Rundstedt, who had initially moved into Witzleben’s quarters in the Louis-Dreyfus mansion, switched to the Villa Félicien David in a less-exposed part of town. Hitler insisted on having a bunker built on the grounds to protect commanders during air raids. But Rundstedt disliked the idea of living underground and refused to use it. He often drove into Paris to stay at his alternate headquarters in the Hotel George V.

Hitler next ordered the engineering group Organisation Todt to work around the clock, using forced labor, to build a mammoth communications bunker in an abandoned quarry. It took 400 men seven months to complete the reinforced concrete structure, which boasts a roof 10 feet thick and walls 7 feet thick. Now covered in ivy and graffiti, the hulk sits abandoned. The fortification of Saint-Germain came around the same time as Hitler’s directive to construct 15,000 defensive structures along some 2,400 miles of coastline from Norway to southern France

—the famed Atlantic Wall, which shifted France’s role from springboard for an invasion of Great Britain to defender against Allied invasion from the west.

By 1943 the U.S. had joined the Allied bombing campaign, which repeatedly targeted the region around Saint-Germain, though not the town itself. The bunkers were never needed, even after the Allies landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. Rundstedt was at Villa David and on high alert when word of the incipient invasion reached him early that morning, but when the Führer finally woke, he ignored his field marshal’s plea for armored reserves. Rundstedt had repeatedly clashed with Hitler over questions of strategy, and after a contentious late June meeting with the Führer at Berchtesgaden, the field marshal ostensibly retired (à la Witzleben) for “health reasons.” Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, a veteran of the Eastern Front, took over in Saint-Germain. Six weeks later, after being implicated in the July 20 assassination attempt on Hitler, Kluge was out (he committed suicide on August 19). After a two-week stint by Field Marshal Walter Model, Rundstedt again took the helm of OB West, but he did not return to Saint-Germain.

German troops had already begun evacuating town as the Allies approached the capital region that August. On the 25th, Saint-Germain’s mayor raised the French flag over the château once again, and the lead American troops entered without opposition the following day. After the May 1945 German surrender the Allies arrested Rundstedt. British prosecutors later indicted him for war crimes, but he was in failing health, and the government ultimately dropped the charges and released him. He died in 1953 at age 77 of heart failure in a Hannover hospital.

After the war refugees briefly inhabited the Saint-Germain bunkers. As the town rebuilt and grew, the structures became part of the urban landscape—a foundation for a house here, a storage facility there. Work crews destroyed a few of the smaller fortifications, but projected demolition costs for the large bunkers proved prohibitive, while any attempt to dismantle the one beside the château risked damaging the centerpiece of Saint-Germain.

A quandary over what to do with the septuagenarian structures persists. Proposals for creating a library or museum in the 10,000-square-foot bunker have fallen apart. Given its damp interior, the three-story complex is unsuitable for even temporary use as storage for treasures from National Archaeological Museum (housed in the château). One lingering question centers on ownership of the structures: The three-story bunker is the responsibility of the Ministry of Culture, others are on public school grounds and thus overseen by the Ministry of National Education, while still others are on private property.

“The residents are accustomed to the bunkers,” says Péricard. “They are just part of the landscape.” The mayor himself recalls a bunker in the back garden of his grandparents’ house—a highlight of childhood adventures.

While most of the bunkers are visible from the street, none is labeled or identified as dating from the occupation. Such is also the case with the Atlantic Wall fortifications on the Normandy coast, immutable witnesses to their own failure. Jérôme Prieur, author of Le Mur de l’Atlantique, notes that while casemates and bunkers were buried or destroyed in many places, they were kept up in Normandy, “like preserving the scene of the crime.”

Saint-Germain’s administration has mapped its bunkers and conceivably could develop a tourism-oriented theme. Few residents support such an effort.

“It’s different going to London to visit Churchill’s bunker than putting forward Rundstedt’s bunker,” Péricard explains, “different psychologically and historically. I am not going to have a ceremony in honor of Rundstedt—it’s unthinkable. They were the occupier, don’t forget.”

During a recent ceremony in Saint-Germain-en-Laye marking the 70th anniversary of the death of famed French General Philippe Leclerc, several veterans voiced their thoughts on the Nazi bunkers. They were wholly indifferent. While the bunkers survive, they pointed out, the Third Reich did not—that is the important point.

The occupation remains a sensitive topic for France, even as the number of those who experienced it firsthand is rapidly dwindling. Péricard notes that generation has kept history alive by sharing stories of the war years with their children and grandchildren, an important aspect toward preserving national identity. He said he would prefer to foster such efforts to preserve the history of Saint-Germain’s people than focus on bunkers installed by enemy occupiers.

“Maybe in 50 or 60 years we will be able to say it was a long time ago, it’s part of our history,” Péricard explains. “But I think for today it is too soon.”

American historian and author Ellen Hampton [ellen hamptonbooks.com] has lived in France since 1989. She has written nonfiction about World War II, curated an exhibit and documentary film about World War I, and is working on a book of historical fiction.