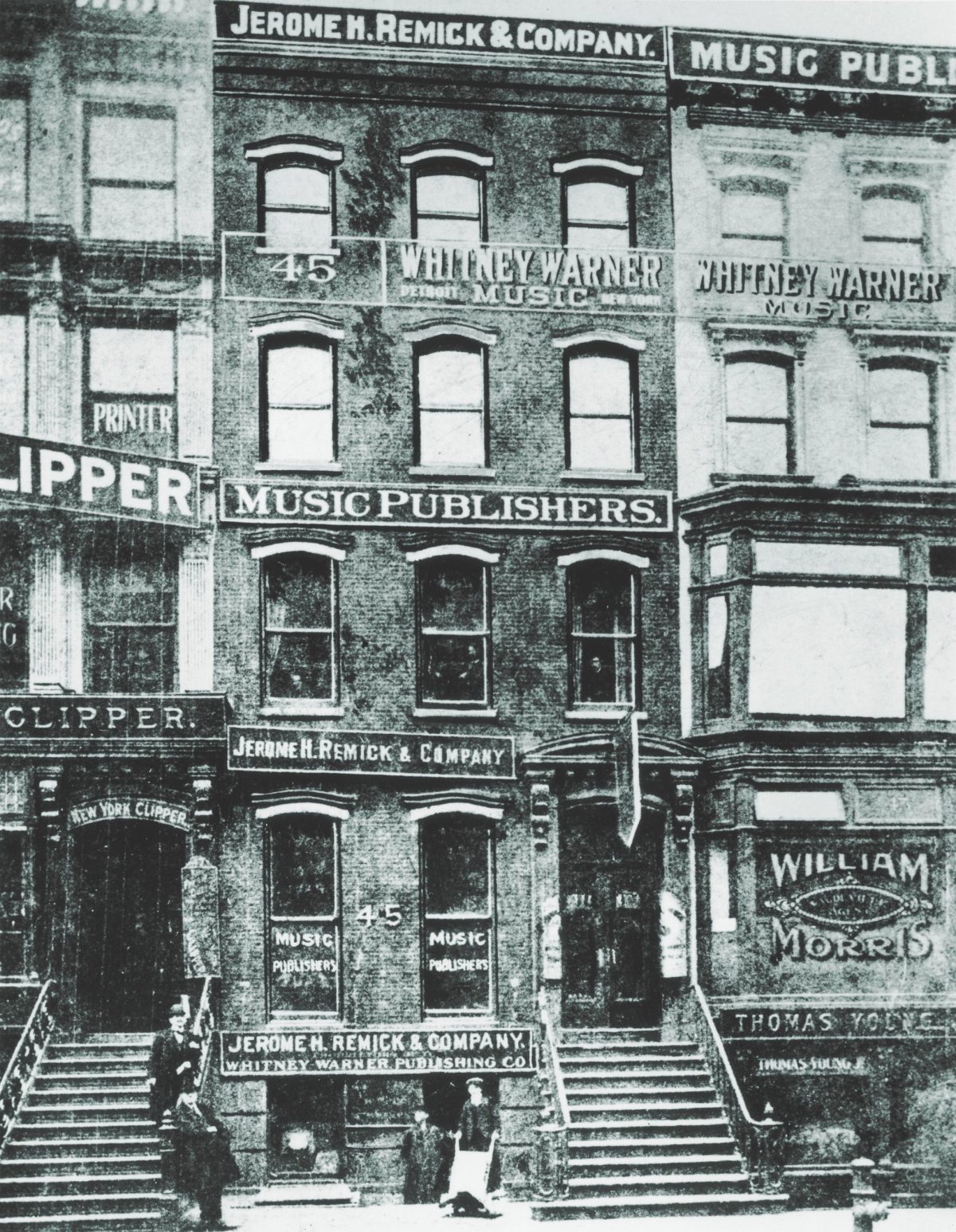

One day in 1903, Monroe Rosenfeld paid a visit to the block of Manhattan’s West 28th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. Rosenfeld, a songwriter and journalist, had come to that neighborhood to call on fellow tunesmith Harry Von Tilzer, one of the day’s best-known songwriters. Von Tilzer kept an office in that locale, and for good reason. On every building along 28th Street signs advertised the music publishers operating within: M. Witmark and Sons, Shapiro-Remick, T.B. Harms, Leo Feist, and others. Through open windows along West 28th blared a cacophony of pianos being pounded in a raucous range of keys and states of tune. Entering Von Tilzer’s office, Rosenfeld greeted his pal.

“It sounds like a bunch of tin cans,” Rosenfeld cracked.

“Well,” Von Tilzer replied, “I guess this must be Tin Pan Alley.”

Several versions of this anecdote exist, and both Rosenfeld and Von Tilzer took credit for the nickname thereafter associated with that stretch of West 28th Street. Gotham newspaper legend holds that Rosenfeld, who wrote for the New York World, had a column called “Tin Pan Alley,” but no supporting evidence has ever surfaced. Nevertheless, in the tradition of stories too good to check, the phrase “Tin Pan Alley” caught on, first referring to the street along which Von Tilzer and rivals toiled and eventually as a synonym for the popular music industry that sprouted in New York around 1890 and blossomed in the first few decades of the 20th century.

Ragtime, which was named for its “ragged” syncopated style, evolved in the late 19th century in Midwestern saloons, dance halls, and brothels.

Tin Pan Alley came into being to serve a market for sheet music, sales of which were indicators of songs’ popularity. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, recorded music existed, first on carnauba wax-coated tubes, then on fragile lacquer disks, but playback equipment was costly. However, Americans were crazy for pianos, and the music they played and listened to on pianos at home, in church, in saloons, and onstage at vaudeville houses and music halls came packaged on paper printed with a number’s key, chords, and, if there were lyrics, words. Tin Pan Alley’s songwriters, song pluggers, and song publishers made their living making music make money, and besides creating a vast body of unforgettable tunes they established what became the American recording industry.

America has always had popular songwriters–in the mid-1800s Stephen Foster had fans humming and singing tunes like “Oh, Susanna,” “I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair,” and “Beautiful Dreamer,” among more than 200 others that he wrote. In Foster’s heyday, the music industry was a scattershot proposition, dominated by hymns and light, classically inflected numbers. Publishers were often music store owners or local printers who distributed sheet music and instrumental instruction books as a sideline, according to Tin Pan Alley by David A. Jansen.

Mass production of pianos changed the market. Following the Civil War, piano sales boomed to as many as 25,000 instruments yearly. Sitting in the parlor with relatives and friends listening to and singing along to the tinkling 88s became a popular middle-class amusement. Often pianists required notation to play songs new to them. Sheet music answered that need. Publication in 1892 of the sheet music to “After the Ball” by Milwaukeean Charles K. Harris set off a trend. Harris’s song tells a story as old as time of heartbreak and loss. “After the Ball” sold two million copies of sheet music its first year at around 50 cents per copy, and by the end of the 1890s had sold five million copies.

Suddenly, music was a business, and everybody wanted in. Entrepreneurs migrated from other sectors. Max Dreyfus, head of the T.B. Harms organization, started out selling picture frames. Edward B. Marks was a notions salesman. Leo Feist sold corsets. Once established in the trade of making musical tastes, these businessmen strove to give Americans what they wanted to hear, sometimes missing the mark. In 1922, neophyte songsmith Richard Rodgers visited Dreyfus to pitch material. “There is nothing of value here,” Dreyfus told the young man. “I don’t hear any music.” Three years later, after Rodgers had written the scores of several Broadway musicals, Dreyfus invited him back and offered Rodgers a contract, Ben Yagoda wrote in American Heritage.

Along with the publishers came a new generation of songwriters: young, ambitious men, often the sons of immigrants, who hired on at a salary to churn out songs of all sorts, from tragedies like Von Tilzer’s “A Bird in a Gilded Cage” to celebrations of transportation, as in Gus Edwards’s “In My Merry Oldsmobile,” and the regional nostalgia of Lewis Muir’s and Wolfe Gilbert’s “Waiting for the Robert E. Lee” to novelty tunes that mocked Blacks, Jews, and other minorities. A vogue for “coon songs” in the minstrel style began to wither around 1905, when African American songwriters and performers denounced them, but it persisted into the `30s.

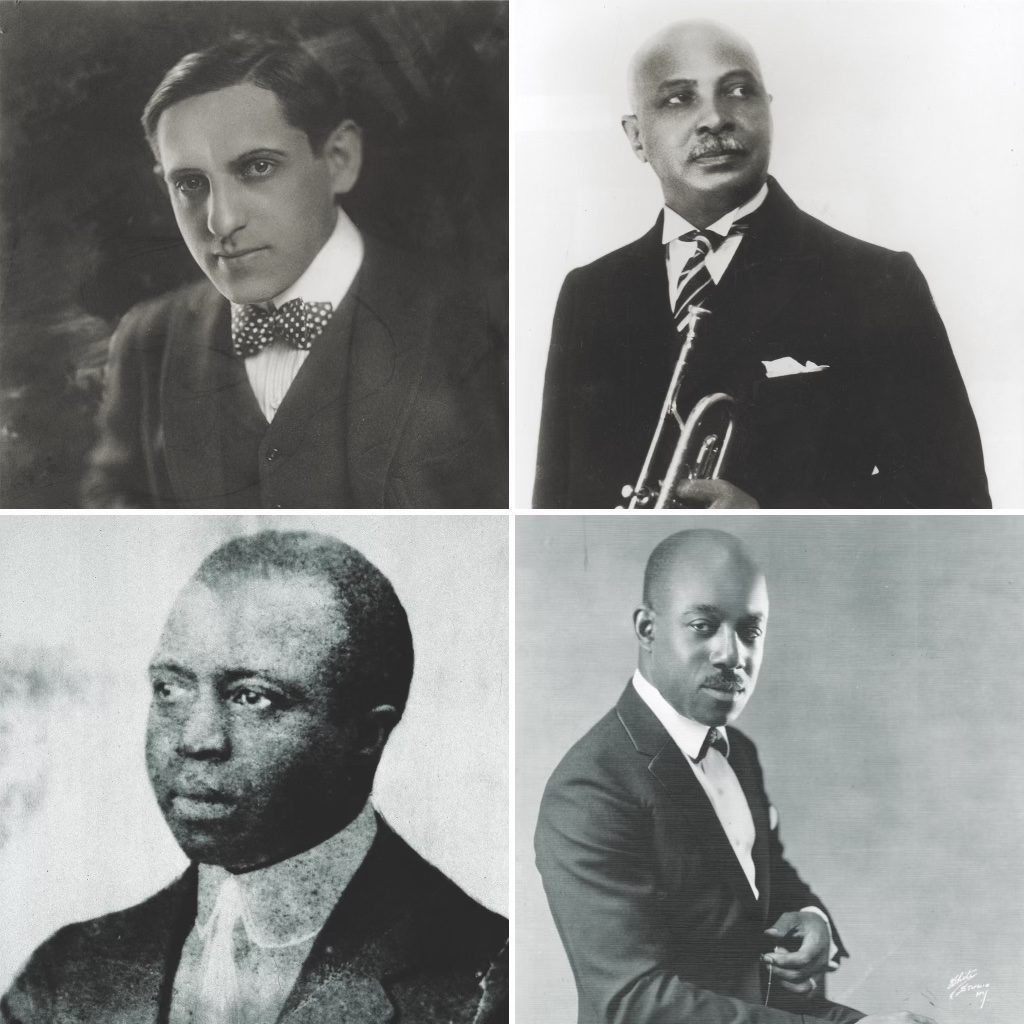

Black composers introduced novel musical forms. Starting in 1909, many set up shop in the new Gaiety Building in Midtown. The first of these genres was ragtime, so called for its “ragged” syncopated style. Ragtime took form in the late 1800s in Midwestern saloons, dance halls, and brothels. In 1899, Scott Joplin, a music teacher, pianist, and composer, walked into music retailer and publisher John Stark’s store in Sedalia, Missouri. Joplin presented Stark with “Maple Leaf Rag,” which began a nationwide craze. Pianists competed in ragtime “cutting” contests, and the music inspired dance steps. Stark publicized Joplin as “king of the ragtime writers” and published more of the composer’s rags, including “The Entertainer.” In 1907, Joplin relocated to New York City, where he tried without success to get his ragtime opera, “Treemonisha,” produced. He reportedly suspected Irving Berlin of having lifted the opening musical phrase of his hit “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” from “Treemonisha,” which Joplin had dropped at Berlin’s publisher. Berlin denied this. Joplin died in 1917. In 1921 Joplin inheritor Eubie Blake made a notable transition from that form to early jazz and show tunes. With partner Noble Sissle, Blake produced and wrote the songs to “Shuffle Along,” the first Black musical on Broadway.

As Scott Joplin was popularizing ragtime, W. C. Handy was pumping up enthusiasm for the blues. Handy, a middle-class Black cornetist and bandleader, had grown up having to hide his interest in music from strict parents. He persisted and became a professional musician. In 1903 he was traveling through Mississippi with an orchestra whose métier was waltzes, marches, light classics, and ragtime, when he heard a guitarist sliding a knife blade across his instrument’s strings, playing “the weirdest music I had ever heard.” Handy was hearing Delta folk blues, whose flatted thirds and sevenths were what sounded “weird” to Handy’s formally oriented ear. Two years later, when Handy and his band were taking a break while playing another Mississippi town, a raggedy string band took the stage and, playing blues, got more applause than Handy’s more genteel ensemble. This convinced Handy that the blues had commercial prospects. In 1912 he sold “Memphis Blues,” titled for his adopted hometown, to a local publisher. In 1914, his new Handy and Pace firm published his “St. Louis Blues.” Handy moved to New York in 1917 and published anthologies of traditional blues and spirituals. He called himself “the Father of the Blues.”

Immigrant and first-generation Jews were prominent along Tin Pan Alley at a time when anti-Semitism was open and pervasive. Hotels barred Jews, help-wanted ads specified “Christians only,” and colleges maintained quotas for Jewish students. Escaping the ghetto meant becoming as “American” as possible, and entertainment was less hidebound than other trades. Many composers of the era were Jewish—Harris, Von Tilzer, Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern, Harold Arlen—as were lyricists like Gus Kahn, “Yip” Harburg, Irving Caesar, and Lorenz Hart. In the time-honored tradition, names changed: Von Tilzer was once Aaron Gumbinsky, George Gershwin was once Jacob Gershowitz, Harold Arlen was Hyman Arluck, Irving Berlin had been Israel Beilin.

In The Jazz Singer, the first full-length sound film, Jakie Rabinowitz, played by Al Jolson, rebels against his father, an Orthodox cantor, by becoming the title character, Jack Robin. Real-world variations on this fictional conflict played out in many Jewish households.

Grinding out songs on salary was mainly a trade pursued by working-class Jews, most of whom, unlike an earlier wave of Landsmen departing German-speaking regions, had immigrated from Russia and Eastern Europe. When Jerome Kern, whose father was a successful German-Jewish businessman in New York City, saw that plugging songs was getting him nowhere, he sailed to London, insinuated himself into that city’s West End musical theater scene, and used the resulting contacts to return stateside and succeed as a Broadway tunesmith. Berlin, raised in a basement apartment on the Lower East Side, did not seek such options.

Some songwriters became publishers. When Von Tilzer’s melodramatic ballad “My Old New Hampshire Home” became a hit in 1898 but only earned him $15, he joined an existing publishing house as a partner. In 1902 he founded Harry Von Tilzer Music. He and other Tin Pan Alley denizens relied on song pluggers who used any means necessary to publicize songs. Biographer James Kaplan recounts how in 1902 young Israel Beilin went to work for Von Tilzer. The tyro’s assignment was to frequent music halls where performers were singing Von Tilzer songs; at the end of his employer’s numbers, he was to jump up and applaud loudly. More refined methods of promotion emerged. Novice songwriter Jerome Kern hired on at Wanamaker’s department store to play a piano positioned on the establishment’s sales floor as a way to encourage sheet music purchases. Kern went on to hawk sheet music to stores up and down the Hudson Valley, eventually going on to great success as a tunesmith. Gershwin quit high school in 1913 to flog songs for potential customers at Remick Music.

Vaudeville was another medium of song promotion. Vaudeville theaters booked varied acts—jugglers, comedians, musicians, singers—that toured regionally and nationally. When troupes played New York, the performers often made the rounds of publishers hunting for new tunes to freshen their acts. In making a reputation for themselves as comedic singers in 1912, the four Marx brothers, raised in Manhattan’s Yorkville neighborhood, paid $27 for “Peasie Weasie,” a tune whose lyrics never came out quite the same when the head Marx, Julius, known as Groucho, sang them. Some vaudeville impresarios wrote songs that they assigned to players in stage companies they ran. Gus Edwards, who wrote “By the Light of the Silvery Moon,” “School Days,” and others, had a “kid act” starring him as an exasperated teacher coping with a clownish class of rising performers such as George Jessel, Phil Silvers, and Eddie Cantor. Young Julius Marx also apprenticed under Edwards.

Another song-selling tool was the player piano, akin to the familiar parlor instrument but able to reproduce music automatically. Powered by foot-pumped treadles, player pianos used piano rolls, continuous sheets of heavy paper perforated to cause the keys to strike chords and notes. Mass-marketed starting in the 1890s and improving steadily in quality into the 1910s, player pianos were immensely popular.

A musician made a piano roll by playing a number as a perforating tool replicated the music on a master sheet used to produce copies. A buyer fitted the roll into the player piano and pumped the treadle. This action moved the roll along and pushed air through its holes, working the piano’s keys. Many songwriters embraced piano rolls not only as a record of their musicianship but as a remunerative sideline. Gershwin’s piano rolls illustrate his breathtaking technique and harmonics; CDs and streamed versions from the original rolls are a revelation. Eubie Blake’s rolls offer a master class in playing ragtime and early jazz.

Sheet music covers promoted their content. Early covers had minimal decoration, but by the 1910s covers were multicolored and illustrated, whether with an image of the songwriter or a performer associated with the number, such as Sophie Tucker or Jolson, a scene reflecting the tune’s content, or, especially for novelty numbers, a cartoon.

Tin Pan Alley proved replicable. Writing in the Chicago Tribune in 1986, June Sawyers explained how the Windy City’s Tin Pan Alley, which dated to the latter 1800s, counted about 50 music publishers in its 1920s heyday. Most had offices downtown, within two blocks of Randolph Street between State and Clark Streets, near today’s Nederlander Theater. Hits originating there included “Down by the Old Mill Stream,” “When You’re Smiling,” “Let Me Call You Sweetheart,” and Fred Fisher’s “Chicago, That Toddlin’ Town.” But the real action was in Manhattan, prompting publishers from Chicago and other cities to establish branch offices in New York City.

Tin Pan Alley produced superstars. The first was George M. Cohan—vaudevillian, songwriter, playwright, actor, and producer of Broadway musicals in which he starred. Cohan came from a tradition of Irish-American musical comedy dating to the 1870s, when Ed Harrigan and Tony Hart in their “Mulligan Guards” comedies lampooned working-class neighborhood militias. As a youth touring with his family’s act, the Four Cohans, George M. Cohan caught the songwriting bug. In George M. Cohan: The Man Who Owned Broadway, John McCabe tells how the novice songsmith pitched a sheaf of songs at Witmark. The publisher bought only “Why Did Nellie Leave Her Home?” Eyeballing the resulting Witmark sheet music, Cohan discovered that all that remained of his composition was the title. But after his first hit show, 1904’s “Little Johnny Jones,” publishers left Cohan and his compositions alone. He went on to write more than 300 songs and to produce and star in more than 30 musicals, composing patriotic show-bizzy numbers like “You’re a Grand Old Flag,”“Over There,” “The Yankee Doodle Boy,” and “Give My Regards to Broadway.” In 1914, Cohan helped found the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), which protects members’ musical copyrights.

Another Tin Pan Alley graduate turned superstar was Irving Berlin. At 15, leaving song plugging behind, Izzy Beilin took a job as a singing waiter at the Pelham Café, a Chinatown dive catering to underworld characters and tourists, and took up piano. In 1907, besides changing his name to Irving Berlin, he sold his first song, “Marie From Sunny Italy,” which he co-wrote with the Pelham Cafe’s house pianist. In 1908, Waterson and Snyder hired Berlin as a staff lyricist. Biographer Kaplan sketches the scene. Dressed in suit and tie and using a fountain pen, Berlin drafted and crafted lyrics for tunes co-owner Ted Snyder and others created. Berlin found inspiration everywhere. When fellow lyricist George Whiting said he could go to the theater that night because his wife had gone to the country, Berlin exclaimed, “That would be a good title for a song!” The two turned Whiting’s remark into “My Wife’s Gone to the Country! Hurrah! Hurrah!” Soon, although he could not read music, Berlin was writing melodies. When an idea struck, he’d bang out a rudimentary version on a piano at Waterson and Snyder; amid the chaos, a sharp-eared “musical secretary” would transcribe his plunking into musical notation. Of his 1911 breakthrough hit “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” Berlin said, “I wrote the whole thing in 18 minutes, surrounded on all sides by roaring pianos and roaring vaudeville actors.”

After “Alexander,” Berlin continued his streak, forming his own publishing company. Enlisting in the U.S. Army as a sergeant during World War I, he wrote an all-doughboy revue, “Yip Yip Yaphank.” In 1921, Berlin and Sam Harris, Cohan’s former partner, opened the Music Box Theater on 45th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues, annually staging “Music Box Revues.” In 1925, the theater started presenting other productions, musical and theatrical. When Hollywood movies entered the age of sound, Berlin segued into soundtracks. His best remembered tunes—“Always,” “God Bless America,” “There’s No Business Like Show Business,” “Cheek to Cheek,” and “White Christmas”—mostly date to his interwar and World War II periods.

Not a few songwriters made the jump from Tin Pan Alley to Broadway, but Gershwin bounded from Tin Pan Alley to the concert hall. Classically trained, he had moved in 1918 from song plugging to composing and writing songs on salary at T.B. Harms for $35 a week. In 1920 Gershwin had his first major success with “Swanee.” His co-writer, young lyricist Irving Caesar, formerly Isidor Kaiser, knew singer Al Jolson, whose recording of “Swanee” made it a hit. That year, Gershwin began to contribute to the annual “George White’s Scandals” revues. For the 1922 “Scandals,” he worked with Paul Whiteman, the decade’s most popular bandleader, who played a watered-down version of jazz. Whiteman repeatedly asked Gershwin to compose a “jazz concerto,” and Gershwin finally did.

The result, “Rhapsody in Blue,” premiered in February 1924 at Aeolian Hall on West 42nd Street with the Whiteman orchestra accompanying Gershwin on piano. He continued to straddle classical and popular music. He wrote the tone poem “An American in Paris,” and composed the opera “Porgy and Bess.” At the same time, with brother Ira as lyricist, Gershwin was writing songs for Broadway and Hollywood that have never gone out of fashion: “I Got Rhythm,” “Embraceable You,” “Our Love Is Here to Stay,” “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off,” and many more.

Given popular song’s ever-changing nature, Tin Pan Alley evolved. The first shift began to be evident around 1910, when music publishers started abandoning 28th Street for the theater district. Besides reflecting the obvious link between songwriting and musical theater, gravitating to the commercial district around 42nd and Broadway was practical. Midtown’s newer buildings offered successful publishers who had expanded their staffs beyond songwriters and pluggers to include sales teams, orchestration departments, and support personnel space for all those people.

A much more significant change took place after World War I, as commercial radio arrived and recording technology matured. Lacquer 78 rpm discs had been the standard in recording since 1910—they held more music and were easier to store than cylinders.

Broadcasting, introduced in 1920, at first put a dent in record sales. Radio stations invited singers and musicians to their studios to play on the air and, beginning with New York’s WHN in 1924, aired broadcasts of popular bands live from ballrooms, nightclubs, and theaters. Introduction in 1925 of electrical recording improved records’ sound quality, reviving sales.

Radio and records complemented each other—a fan hearing an artist perform a song on the air could race to the record shop for a copy. Sitting around the parlor piano listening to some uncle warble along while playing “Mother Machree” became passé. By 1925 record sales outpaced purchases of sheet music and by 1927 had climbed from 1909’s 30 million sales to 140 million.

Throughout the ’20s, the masters—Berlin, Gershwin, Kern, Rodgers and Hart—continued to write great songs. Jazz greats like Thomas “Fats” Waller wrote masterpieces in their idiom. Singer-pianist Waller, who used humor to put his songs over, copyrighted more than 400 numbers and reputedly sold the rights to others for the cash. But the ‘20s also saw a trend of snappy, frothy songs like “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby,” by Walter Donaldson and Gus Kahn, “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn, and “Crazy Rhythm,” by Irving Caesar, Joseph Meyer, and Roger Kahn.

Tin Pan Alley’s glow began to fade when the movies went from silent to sound. Film studios started acquiring music publishers, as in 1929, when Warner Brothers bought M. Witmark, Remick Music, and T.B. Harms, a step toward the establishment of Warner Bros. Records. As corporate units, music publishers went from promoting songs to the public to negotiating with songwriters, documenting and paying royalties, touting tunes to radio station programmers, and licensing their use in commercials and other contexts. The sheet music business withered. Aspiring tunesmiths still were working out tunes on pianos, but now their ambition was not to rack up sheet music sales at Wanamaker’s but to get a Russ Columbo or a Bing Crosby or a Rudy Vallee to put out a 78 featuring a song of theirs. The new era brought a new music publishing hub: the Brill Building at 1619 Broadway, opened in 1931, which publishers shared with talent agencies, entertainment lawyers, arrangers, and others.

In 1939, after a dispute over fees ASCAP charged radio stations for playing songs it controlled, broadcasters formed their own publishing umbrella, Broadcast Music Inc. ASCAP had most of the major publishing firms and songwriters, so BMI sought artists in jazz, “hillbilly” and “race” music, and Latin. In tandem with small independent record companies, BMI-affiliated firms were instrumental in the post-World War II growth of country-and-western and rhythm-and-blues.

In the early 1950s, a few years before rock ‘n’ roll broke out, Brooklyn high schooler Neil Sedaka was writing songs with classmate Howard Greenfield. Sedaka came into contact with a veteran lyricist who had made his name in Tin Pan Alley. In his book Always Magic in the Air, Ken Emerson describes how Sedaka’s Spanish teacher, hearing of his musical avocation, pushed the youth to contact her brother, Irving Caesar. Besides “Swanee,” Caesar, now in his fifties, had written the lyrics for Vincent Youmans’s 1924 hit “Tea for Two.” In 1935, child star Shirley Temple sang Caesar’s “Animal Crackers in My Soup,” in her movie Curly Top, and in 1956 Louis Prima had scored a hit with Caesar’s 1929 composition “Just a Gigolo.” Caesar, who had helped found the Songwriters Guild of America, was still plugging away.

“I met Caesar many times,” said Sedaka, who had his own first big hit in 1959 with “Oh, Carol,” and, as a solo artist and in collaborations with Greenfield at the Brill Building and elsewhere, became a stalwart of the pop music scene. “We never wrote together, but he liked my voice,” Sedaka said of Caesar, “and I sang on many of his demo records.”