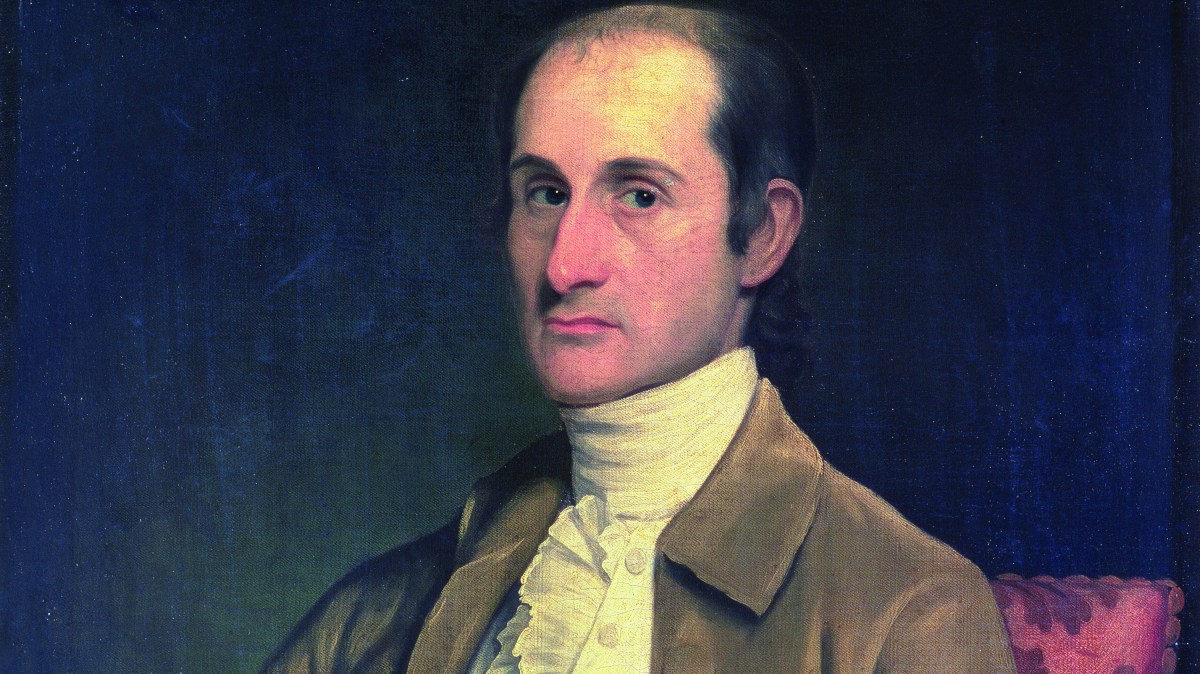

Besides his career in statesmanship and governance, eminent New Yorker John Jay fought valiantly against bondage

The USS Confederacy limped into the harbor at St. Pierre, Martinique, on December 18, 1779. A storm had broken the 36-gun warship’s masts, damaged its rudder, and killed a crewman. Among passengers debarking from the frigate that Saturday was U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary to Spain John Jay, en route to his new posting in Madrid. Accompanying Jay was his wife Sarah, her slave Abbe, a nephew of theirs, and Jay’s personal secretary. Awaiting repairs to Confederacy or a replacement vessel in which to continue their trans-Atlantic journey, Jay and party explored the French-held island. Sarah wrote home about the sugar-producing colony’s superb markets and exquisite beauty. Her spouse took note of a contrasting side of Caribbean life that also caught the attention of Captain Joseph Hardy, commander of Confederacy’s complement of U.S. Marines. In his journal that December, Hardy, in the spelling and locution of the day, explained that passengers and freight moving to and from ships in St. Pierre’s harbor traveled in canoes “rowed by five or six Negroes whose Lives appear to be as wretched as any part of the Human race. Some of them are chained by one leg to the Boat and others shews the stripes of cruelty on their Body’s in this manner these unhappy Mortals row in these Boats for Weeks without 10 hours intermission and as Naked as the moment of their Birth not even the Galley Slaves in Barbary is more misirable.—It is not only these that feels the stripes of inhumanity but many on shore are to be seen with a heavy Iron ring around his Neck from which leads a heavy chain to another ring around his Waist and from that another Ring round his anckle and others dragging by one foot 50 or 60 lb. of Chain and in this situation are obliged to go thro’ their usual service.”

Martinique’s sugar industry ran on slave labor. The fervently religious Jay, convinced the rights of man extended to all men, was haunted the rest of his life by such scenes, which literally put flesh on a reality that had surrounded him all his life. Jay, born in New York City, had spent his childhood in Rye, New York. He had grown up in wealth, his family connected by blood and wedlock to elite New York clans of Dutch and French descent.

All owned slaves; in time, so did John Jay. His father, Peter Jay, and his grandfather, Augustus Jay, a French Huguenot, had been prosperous merchants, fastidiously diversifying holdings that included investing in slave ships, a common and profitable colonial-era practice. In terms of numbers of slaves living and working within its boundaries, New York City rivaled Charleston, South Carolina. In 1740, five years before Jay’s birth, enslaved persons had made up almost 20 percent of the total New York population. Jay’s visceral reaction to the slave-driving he witnessed in Martinique was not enough to dissuade him from buying a 15-year-old slave named Benoit and taking the youth along to Spain and his other postings.

In September 1780, while in Spain negotiating to gain that monarchy’s support for the American cause, Jay pondered the horrors he had seen on Martinique. In a letter to friend and New York State Attorney General Egbert Benson, Jay wrote, “The State of New York is never out of my mind and heart. An excellent law might be made…for gradual abolition of slavery. Till America comes into this measure, her prayers to Heaven for liberty will be impious. This is a strong impression, but it is just. Were I in your legislature, I would prepare a bill for the purpose with great care, and I would never leave moving it till it became law or I ceased to be a member. I believe God governs the world, and I believe it to be a maxim in his as in our court, that those who ask for equity ought to do it.”

The conflicted Jay had acted fitfully against slavery, backing a failed abolition provision in New York’s 1777 state constitution. Early in the Revolution, he had worked with his friend Alexander Hamilton to convince General George Washington to allow bondsmen to toil as laborers and later to carry guns for the American cause, with freedom their reward if the rebellion succeeded.

Like many fellow revolutionaries, Jay took as gospel Enlightenment rhetoric extolling the innate rights of man. He avidly ingested such philosophy and political theory entering adulthood in the 1760s. He began acting consciously to make those ideals manifest in his homeland as part of the rebellion against Great Britain. His early steps against slavery had been theoretical and tepid. Now, having seen the phenomenon unvarnished, John Jay meant to eliminate its scourge in New York.

Jay started his personal crusade in Europe, just after the signing of the Treaty of Paris. In November 1783, Sarah’s slave Abbe ran off, going to ground in the French capital. Jay wrote to a friend that Abbe’s flight “was not resolved upon in a sober moment.” He explained that he “had promised to manumit her on our Return to America, provided she behaved properly in the mean Time.” He surmised that “Indulgence and improper Company have injured her. It is a Pity.” Jailed as a runaway bondswoman—the empire kept human chattel on a tight rein—Abbe fell ill. She was returned to her owners, whose best efforts at care could not keep her alive.

Soon after Abbe died, Jay wrote a manumission contract for Benoit, now 19, in which Jay declared, “hav[ing] served me until the value of his services amount to a moderate compensation for the money expended for him, he should be manumitted; and whereas his services for three years more would, in my opinion, be sufficient for that purpose.”

Jay made good on that proposed arrangement and in later years repeated the gesture with other slaves that he bought, often paying his enslaved workers wages in the bargain.

Early in 1785, Jay and other New York leaders, including Alexander Hamilton, founded the “New-York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and Protecting Such of Them as Have Been, or May Be Liberated,” better known as the New York Manumission Society. Pursuing the larger aim of abolishing slavery in New York, the Society legally assisted enslaved people and former slaves against kidnap and worked to ensure their rights as citizens of New York. The group also educated free Black children. Organizers elected Jay their first president.

Almost from its founding, the Society began pushing a gradual emancipation bill in the state legislature. Contrary to similar measures elsewhere, this proposal would manumit the currently enslaved, though, as a palliative to owners, to gain freedom men would have to serve 25 years of indenture and women 22. Enthusiasm for the concept eroded amid resistance to the details. Slaveholders and their allies balked at the indenture arrangement. Others worried about how freedmen would fit into society, some voicing doubt of manumitted Africans’ readiness for citizenship and suffrage. In a bitter 1785 defeat, the bill foundered on the shoals of property rights, economic stability and racism.

Not only had Society members assumed naively that egalitarian principles expressed during the Revolution regarding all persons would persist in peacetime, they had readied no effective retort for proslavery arguments. But they did succeed in 1785 in getting New York to ban import of slaves into the state. Unsatisfied with that baby step, Society members began laying groundwork for more campaigns. Jay corresponded at home and abroad with fellow abolitionists. These exchanges often found Jay on the defensive. Reassuring Dr. Benjamin Rush of his group’s commitment, Jay wrote that he “wish[ed] to see all unjust and unnecessary discriminations everywhere abolished and that the time may soon come when all our inhabitants of every colour and denomination shall be free and equal partakers of our political liberty.” Answering Welsh moralist Richard Price, Jay wrote, “That men should pray and fight for their own freedom, and yet keep others in slavery, is certainly acting a very inconsistent, as well as unjust and, perhaps impious part; but the history of mankind is filled with instances of human improprieties.” The best anyone can do is to persevere against evil and dutifully work toward a just society, he added.

In 1787, the Manumission Society founded an African Free School in lower Manhattan to educate the children of free Blacks. Many society members belonged to the Society of Friends, or Quakers, by now a strong voice on behalf of abolishing slavery. In running its school, the manumission organization embraced Quaker practices such as visiting students’ homes to enforce moral behavior in the household. To counter racist assumptions about Blacks, the Society carefully recruited and selected the students it enrolled. The Free School operated until 1835, when the New York City school system absorbed it.

Meanwhile the organization encouraged members and all others to manumit persons held in bondage. Society officers believed that “the good Example set by others, of more Enlarged and liberal Principles, and the face of true Religion, will, in time, dispel the mist which Prejudice, self Interest and long habit have raised….”—an awkward sentiment, given that Jay and many other members owned slaves.

Many slaves confiscated from Loyalist owners during the Revolution and held by the state government had been sold back into bondage. The Society demanded and got an amendment stipulating that all remaining slaves still held by the New York government be freed. And the Society’s efforts to find and unshackle freed Blacks who had been kidnapped and sold south led in 1788 to a ban on exporting bondsmen and -women for sale to buyers in slave states, infuriating slaveholders.

On September 26, 1789, the Senate unanimously confirmed John Jay as the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. To avoid the appearance of conflict of interest, Jay resigned the Manumission Society presidency, but informally continued his abolition work.

In New York, a proslavery legislative backlash arose. When Society member Matthew Clarkson introduced a gradual emancipation bill in 1790, that piece of legislation stalled, as did kindred efforts to strangle the slave trade. In 1792, the backlash broadened. That year Jay did as many Federalists suggested and challenged four-time governor George Clinton at the polls. Jay seemed poised to win until opponents played the abolitionist card. Jay would not renege on his principles. “Every man, of every colour and description, has a natural right to freedom,” he declared. “And I shall ever acknowledge myself to be an advocate for the manumission of slaves.” Clinton won a fifth term.

Events began to work in abolition’s favor. America’s conflict with Algerian pirates who enslaved White Americans refocused discussion: Why go to war over enslaving Whites but not Blacks? Slavery suffused the debate over ratifying the Constitution, which nowhere contains the word “slavery” but instead refers to enslaved persons, leaving inspecific the governmental role regarding abolition of slavery.

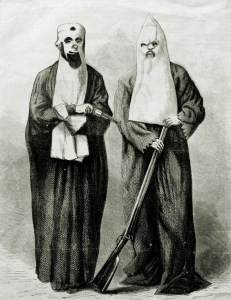

These debates also raised the issues surrounding the end of the foreign slave trade, slated in the U.S. Constitution for 1808, and the formulation of the Three-Fifths Compromise, an equation that increased Southern states’ political power by mandating that slaves be counted in the national census as three-fifths of a White person. Against this backdrop, New Yorkers debated what kind of society they wanted and worried about bondage’s potentially negative economic impact. Thanks to the Manumission Society’s work and a growing population of free Blacks, journalists were filling the state’s periodicals with reports of Blacks integrating successfully into the majority society. Meanwhile, the Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791, was eventually to overturn French rule and emancipate Haiti’s slaves, heightening concerns about slave revolts as a feature of a slaveholding society. In New York, the state’s White population growth had shifted north and west, coming to be dominated by farmers and merchants who owned no slaves and were not about to support slave interests through taxes or other means.

While Jay was in England during 1794-95 negotiating a treaty to ease tensions with the crown, New York held another gubernatorial election. Jay’s friends nominated and won him the office, advocacy he may or may not have known of. Jay returned having accomplished his diplomatic mission to find himself governor-elect—and pilloried for what became known as “Jay’s Treaty,” an achievement that may have benefited the abolition cause by helping to “nudge New York past an obstacle to gradual abolition,” according to historian David N. Gellman. Although Jay’s treaty focused on issues that lingered between America and Britain after the 1783 Treaty of Paris, that document ignored the matter of compensation to colonial slaveholders for slaves said to have been “stolen” by the British during the war. Gellman argues that after the American colonies’ fight for liberty from Britain, Jay and others felt loath to compensate slaveholders for enslaved persons who sought emancipation by fleeing to and fighting for the British.

Proslavery forces continued to challenge every abolition bill floated in New York. Jay, determined to keep his 1780 promise, thought it prudent to absent himself from the public process, lest he become the focus of debate. In January 1796, state Representative James Watson, acting as Jay’s proxy, introduced a gradual abolition bill. The measure stalled when slaveholders argued against citizenship rights such as suffrage for manumitted persons. Naysayers insisted the state compensate former owners for freeing their bondsmen. However, abolitionists had learned their lessons. The Manumission Society had begun making effective use of the legal system to free numerous slaves and to rescue free Blacks at risk of kidnap back into bondage. The cost to appeal the resulting court rulings was giving slaveholders pause. Emergence of governmental and charitable aid to the needy was weakening the argument that, once freed, help for indigent Blacks would create an unworkable drag on the state.

Most importantly, abolitionists realized that they needed to find a way to work with slaveholders. A 1798 effort also stalled, mainly over remuneration, but abolitionists engineered a compromise.

On March 29, 1799, the New York legislature passed a gradual emancipation bill taking effect that July 4. Children born to enslaved mothers after Independence Day 1799 would be free but would have to serve their birth mothers’ masters under indenture until age 28 for males, 25 for females. As of July 4, slaveholders would have to register children newly born to enslaved mothers, not only to record manumissions but also to document emancipation as a defense against attempted kidnap or transport south. Abandoned slave children would become wards of local jurisdictions. The bill allowed unrestricted manumission of elderly or unproductive slaves. Jay’s son William wrote years later that his father felt “no measure of his administration afforded him such unfeigned pleasure” as that bill’s passing and enactment.

Jay had achieved what he envisioned almost 20 years before, but that achievement continued to come under attack, as did free Blacks’ political rights. A gap in the 1799 bill had relegated Blacks born into slavery in New York before 1799 to continued enslavement. In 1817, Jay’s eldest son Peter, a member of the legislature, worked with Governor Daniel Tompkins to order that, effective July 4, 1827, those born before 1799 would be deemed free. Another son, William Jay, fought slavery nationally and as a judge stated that he would not abide by any laws requiring the return of fugitive slaves. Jay’s grandson John Jay II maintained a similar stance.

Retiring in 1801, John Jay continued to correspond with fellow abolitionists, at times lending support while trying to avoid national political entanglements—save for an episode in 1819. That year New Jersey lawyer Elias Boudinot, who had founded the American Bible Society, wrote to Jay asking about the constitutionality of extending slavery into Missouri, which had petitioned for statehood. “I concur in the opinion that it ought not to be introduced nor permitted in any of the new States; and that it ought to be gradually diminished and finally abolished in all of them,” Jay replied. “To me the constitutional authority of the Congress to prohibit the migration and importation of slaves into any of the States does not appear to be questionable.” Because Article 1, Section 9, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution mandated in 1788 an end to the foreign slave trade in 1808, Congress had the right to restrict slavery, he continued, claiming “that from and after that period [1808], they were authorized to make such a prohibition, as to all the States, whether new or old.” He went on to explain, “It will, I presume, be admitted, that slaves were the persons intended. The word slaves was avoided [in the U.S. Constitution], probably on account of the existing toleration of slavery, and of its discordancy with the principles of the revolution….”

He encouraged those trying to keep slavery out of Missouri, but, pleading poor health, declined to join that fight. On May 17, 1829, John Jay died of a stroke in Bedford, New York. In 1854, Empire State newspaperman Horace Greeley wrote, “To Chief Justice Jay may be attributed, more than to any other man, the abolition of Negro bondage in this state.”

This story was originally published in the October 2021 issue of American History Magazine. For more great stories, subscribe here.