Lacking any kind of recording apparatus, people in the mid-19th century could hear popular songs only through live performances—at minstrel shows, concerts or maybe in the family parlor accompanied by piano. Nonetheless, the war years were alive with songs that were learned and sung throughout the North and South. “An endless stream of compositions poured forth from the dedicated pens of scores of professional song writers and hundreds of eager amateurs,” writes Irwin Silber in Songs of the Civil War. Helped by a healthy sheet music industry—some middle-class families would reserve a cabinet just for their music collection—popular songs spread like wildfire.

The Hutchinson family of New Hampshire was one influential conduit for new songs. A brood of 16 musically inclined offspring sired by parents Jesse and Mary, the family introduced audiences to musical works by many composers. Among their fans was Abraham Lincoln, who heard them perform in Springfield and at the White House. In 1862 Lincoln had to personally intervene when the family performed the abolitionist song “We Wait Beneath the Furnace Blast” for the Army of the Potomac. General Philip Kearny thought the performance was too “incendiary” and barred them from singing for the army again—an order that was countermanded only after Lincoln stated that the tune was “just the character of the song that I desire the soldiers to hear.”

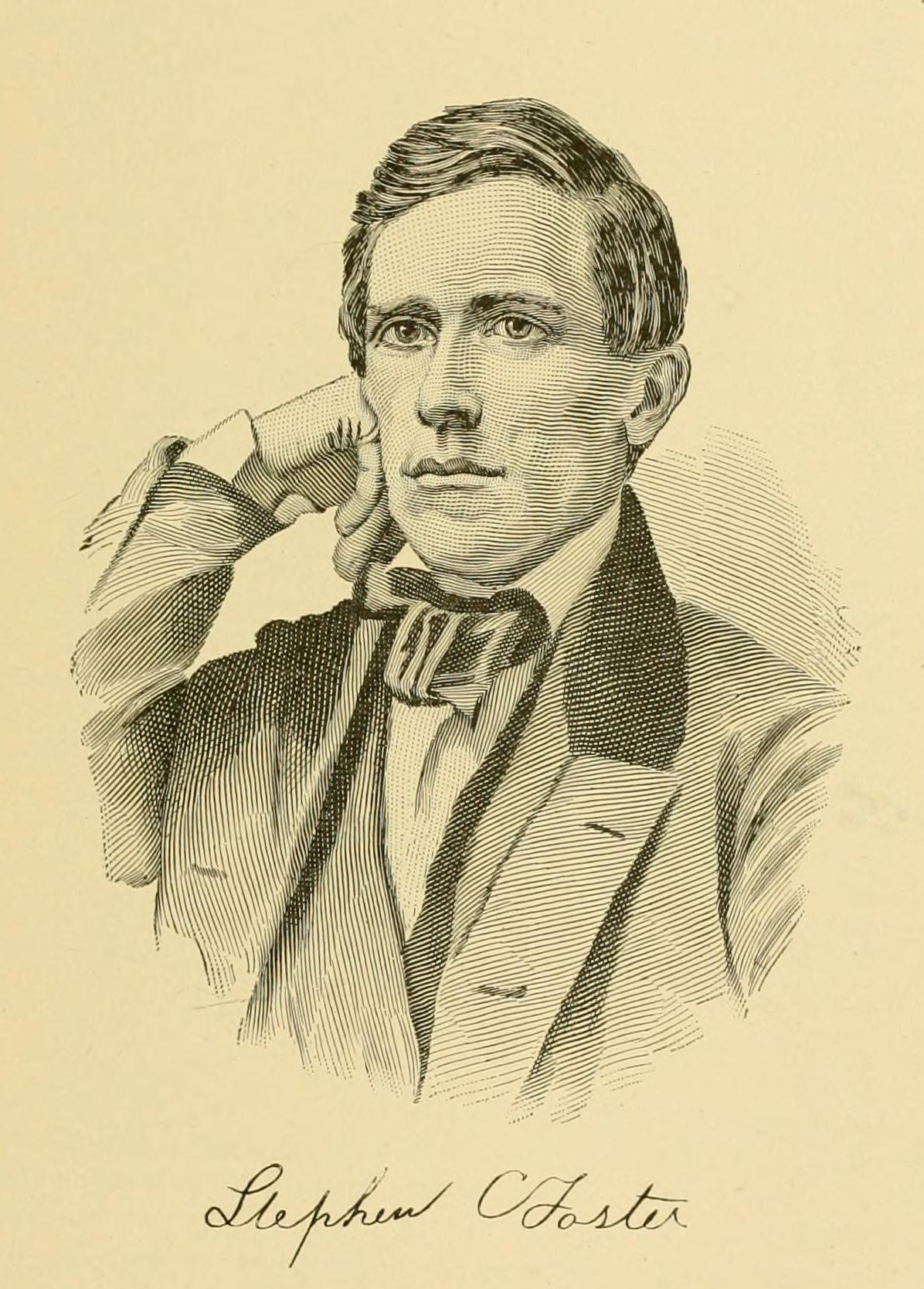

The greatest songwriter of the era was Stephen Foster, although his star was in decline by the time war broke out. “In any history of popular music in America his name leads all the rest,” writes Sigmund Spaeth in his exploration of popular American music. Although Southern sentimentality tinges much of his work, Foster was a Pennsylvania native who spent little time below the Mason-Dixon Line. And he was initially so ashamed of what he called his “Ethiopian” songs that he allowed others to put their names on them—including the great minstrel E.P. Christy, who originally took credit for “Old Folks at Home.”

Foster suffered a creative slump in the late 1850s, but in 1860 he scored a hit with “Old Black Joe.” After Fort Sumter he tried his hands at war songs, including “We Are Coming, Father Abraam,” “We’ve a Million in the Field,” “Was My Brother in the Battle?” and “Better Times Are Coming,” but as Spaeth notes, “People were no more interested in bad war songs then than they are today.” Foster wrote only one more memorable song, “Beautiful Dreamer,” before he died in Bellevue Hospital’s charity ward in 1864, an alcoholic with only 38 cents to his name.

Like Foster, Daniel Decatur Emmett was a Northerner whose songs captured Southern hearts, especially a song he called “Dixie’s Land” but which is better known simply as “Dixie.” Emmett was a singer, dancer, instrumentalist and a popular performer in minstrel shows, where he sang many of his own songs, including “The Blue Tail Fly” (aka “Jimmy Crack Corn”). Emmett wrote his great ode to the South in New York City one November Sunday in 1859. He got his subject matter when his wife complained about the dreary Northern weather. “I wish I was in Dixie,” she said. “It made a hit at once,” Emmett recalled in an interview, “and before the end of the week everybody in New York was whistling it. Then the South took it up and claimed it for its own. I sold the copyright for five hundred dollars, which was all I ever made from it.” In 1861 New York publishers issued Northern versions, “Dixie for the Union” and “Dixie Unionized.” Southerners responded with their own alternate arrangements that directly addressed the issue of war. One began, “Hear ye not the sounds of battle?”

Another song guaranteed to warm Southern hearts was “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” written by music hall veteran Harry Macarthy, and “The Arkansas Comedian,” from an Irish melody. Southerners loved the song, but Union General Benjamin Butler did not. While commanding the occupation of New Orleans, Butler fined anyone heard playing, whistling or singing the song $25.

A different song got composer Septimus Winner in trouble. Winner is remembered today for using a German melody to accompany the words “Oh, where, oh where, has my little dog gone,” but in 1862 he wrote “Give Us Back Our Old Commander” to protest the removal of General George B. McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac. The song was a hit, and 100,000 copies of the music were sold, but Secretary of War Edwin Stanton promptly declared singing of the song an act of treason and threatened its composer with imprisonment. Stanton was mollified after Winner promised to stop promoting the song.

George Frederick Root had better luck with his war songs. Born in 1820, he initially used the pseudonym Wurzel and had hits in the 1850s with “The Hazel Dell” and “There’s Music in the Air.” Three days after Fort Sumter, Root published “The First Gun Is Fired,” and he contributed popular martial songs throughout the war, including “Just Before the Battle, Mother,” “Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!” and most notably “The Battle Cry of Freedom.” As one Union soldier recalled, the song “ran though the camp like wildfire….Day and night you could hear it by every campfire in every tent.”

Two songs still sung today are “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.” Julia Ward Howe wrote the words to the “Battle Hymn” by candlelight one night while she was staying at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. She published her poem in The Atlantic Monthly and set the words to an old tune called “Glory Hallelujah.” “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” was published in 1863 and credited to “Louis Lambert,” but the composer was really Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore, an Irishman who became the Union Army’s bandmaster. Long after the war that provided their inspiration ended, these songs live on.

Originally published in the May 2006 issue of Civil War Times.