Less than 20 years after the last guns of the War of Independence fell silent and 12 years since the adoption of the Constitution, the young American republic found itself in the midst of a political crisis that threatened to lead to armed rebellion and disunion. An extraordinary cascade of events forced the nation’s elected leaders to choose between pursuing their partisan goals and buttressing constitutional foundations. While the union of the Founders survived, their vision of a nonpartisan polity was swept away, replaced with a party system very familiar to us 207 years later.

When the framers of the Constitution designed the Electoral College, they envisioned nonpartisan elections, with each state choosing leading citizens as its electors. In some states, voters chose electors by popular ballot, in others state legislators picked the electors. The electors of each state would then meet in a “collegial” setting and cast one vote for each of two different individuals thought best suited for the presidency. The top vote getter with at least a majority of electors would become president; the second-place finisher would become vice president.

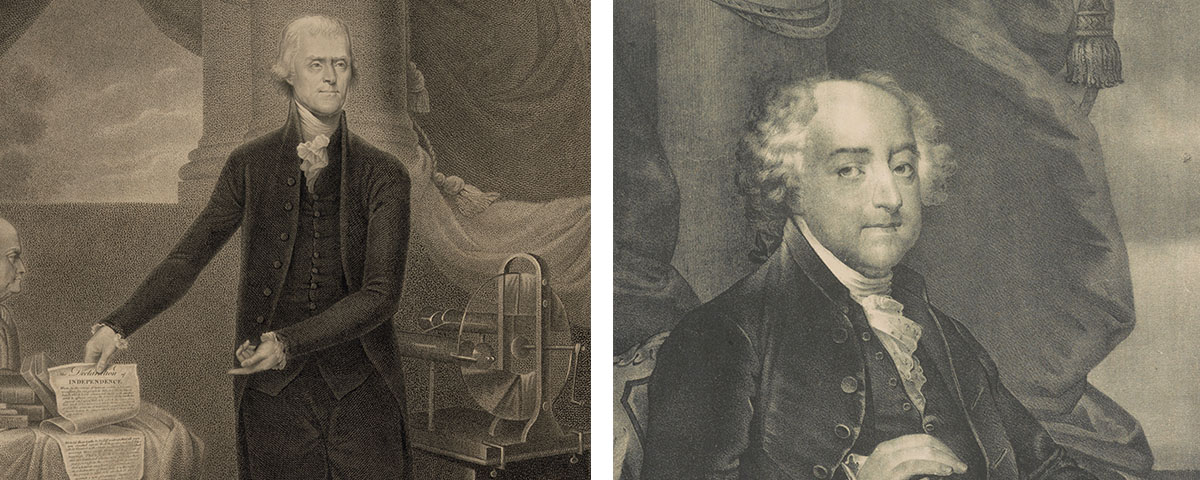

If no one received votes from a majority of the electors, or if the election ended in a tie, the House of Representatives would choose the president from the leading candidates. Alien as it seems today, the process worked pretty much as the framers intended in the first three presidential elections, without overt partisan campaigning by the candidates and with the electors exercising their independent judgment. Indeed, the 1796 election resulted in Federalist John Adams as president and Republican Thomas Jefferson as vice president.

The election of 1800, however, was like no other in American history. It was the first time that parties mounted presidential campaigns, as domestic and foreign developments had divided Americans into two distinct partisan camps: the Federalists of President Adams and Alexander Hamilton—ideological ancestors of modern Republicans—versus the Republicans, or the future Democrats. Virtually every member of Congress had aligned himself with one party or the other.

The Federalists saw a strong central government led by a powerful president as vital for a prosperous, secure nation. Extremists in this camp, such as Hamilton, favored transferring virtually all power to the national government and consolidating it in a strong executive and aristocratic Senate. Vice President Jefferson and his emerging Republican faction, however, viewed such thinking as inimical to freedom. Jefferson trusted popular rule and distrusted elite institutions: “The will of the majority, the natural law of every society, is the only sure guardian of the rights of men,” he wrote in 1790.

Early in 1800, congressmen and senators of each party caucused in the nation’s capital to nominate their candidates for national office. The Republicans united behind Jefferson; the Federalists split, with moderates backing the incumbent Adams, and the ultra or high Federalists supporting Hamilton’s favorite, Revolutionary War General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

With the election expected to be close, the notion of independent electors was abandoned, and all electors were chosen as proxies for partisan presidential nominees. Full-fledged campaigns for president developed everywhere. In states where legislators chose the electors, these campaigns played out in electing legislators. In states where voters chose electors directly, the campaigns were fought over electors who pledged to one party and its candidates. Although voters did not vote directly for president, for the first time the presidency was clearly the main prize when they cast their votes for partisan candidates for legislator or elector.

In a show of solidarity, the Federalist caucus urged Federalist electors to cast one vote each for Adams and Pinckney, with both sides conspiring to gain the advantage in the final count. Republicans called for their electors to vote for Jefferson and Aaron Burr, former attorney general of New York and influential state assemblyman, with the intention of Jefferson becoming president and Burr becoming vice president.

Even though the Constitution mandated that electors cast their votes on the same day, the various state elections that determined the electors were spread out over the better part of a year. Party leaders watched their totals build and the lead change hands repeatedly. No one knew who would win until after the last state—South Carolina—chose its electors on the very eve of the prescribed day for the Electoral College to meet. Because of the delays in communication, however, the election remained in doubt to the very end.

So Who Becomes President?

Electors from all 16 states cast their votes on December 3, 1800. Although Congress would not open and count the ballots until February 11, 1801, electors could, and did, tell people how they voted. By the third week of December, a pattern of highly disciplined party-line voting had become quite clear. Republican electors had voted with such unity that Jefferson and Burr would likely end up in a dead heat with 73 electoral votes each. The best estimates had them finishing eight votes ahead of Adams and nine in front of Pinckney.

This development, even though he had foreseen it as a possibility, shocked and deeply troubled Jefferson. “It was badly managed not to have arranged with certainty what seems to have been left to hazard,” Jefferson wrote to Burr on December 15. “I never once asked whether arrangements had been made…[for] dropping votes intentionally…nor did I doubt till lately that such had been made.” Burr did not respond. By December 19, Jefferson knew the final tally. “There will be an absolute parity between the two Republican candidates,” he wrote to fellow Virginian James Madison from Washington. “This has produced great dismay and gloom on the Republican gentlemen here, and equal exultation in the Federalists.”

The Federalists had some reason to be exultant about a tie vote, for a House of Representatives that included many lame-duck Federalists would now choose between two Republican candidates for the presidency, as called for in the Constitution. Each state had one vote, which would go to the candidate supported by a majority of congressmen in the state’s delegation. If the delegation of a state split evenly, that state would abstain.

With 16 states, an absolute majority of nine votes was required for victory. Jefferson keenly calculated and recalculated his chances. He felt confident that he would receive votes from all eight state delegations that had a majority of Republican members. Jefferson reasoned that Republicans uniformly considered him as their party’s candidate for president and, furthermore, that the electors and people had voted with such an understanding.

But the Federalists could deadlock the House until March 3, the day Adams’ term as president and Jefferson’s term as vice president ended. Under the Constitution, if the top two posts become vacant, the president pro tempore of the Senate acts as president. As long as the vice president was the Senate’s presiding officer, however, the Senate did not have a president pro tempore. So, while he remained vice president, Jefferson could stop the Federalist-dominated Senate from electing a president pro tempore simply by attending every session in his constitutional role as president of the Senate, which he vowed to do. This still left open the question of what might happen if the Senate remained in session after the vice president’s term of office expired.

Further, the Constitution clearly authorized Congress to make laws designating which officer would lead the nation in the absence of both a president and vice president. A specific Cabinet member or judicial officer could assume power in such a crisis, and Jefferson realized that this offered the Federalists a second means to cling to power after March 3. In particular, he worried that they would designate as the next in line for presidential succession either the secretary of state, then Virginia Federalist John Marshall, or the chief justice of the Supreme Court, probably Federalist senior statesman John Jay, who Jefferson presumed would soon fill that then vacant post.

To Republicans, either approach would constitute a naked usurpation of power. Federalist leaders in Congress did in fact consider both options, as well as another—the extraconstitutional alternative of calling a new national election. The Federalist press openly defended all three approaches for retaining power. Republican newspapers railed against them and, in one widely reprinted response, the National Intelligencer argued that if March 3 came and went without the election of a president, the Articles of Confederation “will be revived by the termination of the…federal Constitution.” Although of doubtful authority, this response raised the stakes for the Federalists, whose very existence as a party was identified with the effort to ratify and then defend the Constitution.

A more likely scenario, however, had Burr conspiring with the Federalists and a handful of Republican congressmen to win the election in the House. Republicans held only a slender advantage in several of the congressional delegations that they controlled. In Vermont, New Jersey, Maryland, Georgia and Tennessee, a single Republican defection could turn the state’s vote against Jefferson. Two defections in the New York delegation could swing Burr’s home state. If every Federalist congressman voted for him, Burr would need only three or four strategically placed Republican votes to carry the needed nine states.

Never short on self-confidence, Burr reportedly believed that he could win the presidency. To Jefferson, however, he professed his loyalty. In a December 23 letter written before Burr knew of the final electoral-vote count, he assured Jefferson that “My personal friends are perfectly informed of my wishes on the subject and can never think of diverting a single vote from you.” After becoming aware of the tie, however, Burr became so equivocal in his comments that no one could be sure of his intentions.

Virtually all Federalists in Congress regarded Burr as grasping, selfish and unprincipled. “A profligate without character and without property—a bankrupt in both,” Federalist Speaker of the House Theodore Sedgwick called him. Those very traits made him all the more likely, though, to cooperate with them in maintaining a strong national government. “By persons friendly to Mr. Burr, it is distinctly stated that he is willing to consider the Federalists as his friends and to accept the office of President as their gift,” Delaware Rep. James A. Bayard asserted. Virginia Congressman Henry Lee added, “He must lean on those who bring him to the chair, or he must fall to never rise again.” In short, by electing him president, Federalists hoped to turn Burr into their creature.

Federalists also viewed Burr as more vigorous and pragmatic than Jefferson, whom they scorned as a cowardly, misguided visionary. Sen. William Hindman of Maryland wrote of Burr, “He is a soldier and a man of energy and decision.” “If Mr. Burr succeeds, we may flatter ourselves that he will not suffer the executive power to be frittered into insignificance,” declared James McHenry, Adams’ former secretary of war. Federalists also anticipated that Burr, as a New York commercial lawyer, would support Federalist business interests more than Jefferson, a Virginia agrarian. “His very selfishness,” Sedgwick wryly noted of Burr, “will afford some security that he will not only patronize their support but their invigoration.” By the beginning of 1801, then, Burr had become the Federalists’ white knight. No solid evidence exists that he ever promised Federalists anything in exchange for their support but, faced with the prospect of losing power for the first time, they simply gave it to him on faith.

With the Federalists clearly defeated, President Adams took no part in the final phase of the election. Although he favored Jefferson over Burr, Adams left the decision entirely to Congress. On the final day of December, though, he vented his feelings about Burr and the partisanship that would lift him to national office. “How mighty a power is the spirit of party! How decisive and unanimous it is! Seventy-three for Mr. Jefferson and seventy-three for Mr. Burr,” Adams wrote. “All the old patriots, all the splendid talents, the long experience, both of Federalists and Anti-Federalists, must be subject to the humiliation of seeing this dexterous gentleman rise, like a balloon filled with inflammable air, over their heads.”

Meanwhile, Hamilton, who had publicly split with Adams and worked against his reelection, tried to stop his party’s mad rush to embrace Burr. Jefferson became the lesser of two Republican evils: “If there be a man in the world I ought to hate, it is Jefferson,” Hamilton wrote, “but the public good must be paramount to every private consideration.” He launched an extraordinary letter-writing campaign to Federalists in Congress portraying Burr as a cunning, diabolical intriguer willing to say or do anything to gain political power and private wealth. “Burr loves nothing but himself; thinks of nothing but his own aggrandizement; and will be content with nothing short of permanent power in his own hands,” Hamilton admonished Congressman Harrison Gray Otis of Massachusetts. He cautioned South Carolina’s John Rutledge that if Burr “has any theory, ’tis that of simple despotism.”

Hamilton, however, had lost credibility in his own party. In October 1800, against the advice of friends and colleagues, he had printed a vicious 54-page screed against Adams. Now, in the wake of the devastating defeat of his hand-picked candidates by Burr’s slate in New York’s state elections in April, Hamilton simply sounded vindictive. The congressmen all responded to Hamilton, expressing their determination to back Burr.

A Contest for Votes

Conditions in the nation’s new capital aggravated partisan divisions. In cosmopolitan Philadelphia, lawmakers met in the historic old State House and enjoyed the distractions of the nation’s largest and most cultivated city. In frontier Washington, politics consumed them. There was little else to do. “A few, indeed, drink, and some gamble, but the majority drink naught but politics,” House Republican leader Albert Gallatin of Pennsylvania wrote in mid-January about his colleagues, “and by not mixing with men of different or more moderate sentiments, they inflame one another. On that account, principally, I see some danger in the fate of the [presidential] election which I had not before contemplated.” Federalists and Republicans had mixed freely in Philadelphia society. In Washington, however, they rarely met except in partisan combat.

With less than two weeks until the critical House vote for president, trust had broken down completely between the parties. Each side attributed only the worst motives to the other. By the middle of February, lawmakers were in no mood to compromise, or even to act rationally. When President Adams issued an advance call for a special session of the new Senate, ostensibly to confirm the next president’s appointments, some Republicans smelled a rat. Knowing that Federalists would still dominate this body until the states chose their new senators, Republicans feared that the rump Senate would promptly elect a Federalist president pro tempore to assume the reins of government.

According to his own account, Jefferson verbally threatened Adams with “resistance by force and incalculable consequences” if the Federalists tried to install an interim president. “We thought it best to declare openly and firmly, [to] one and all, that the day such an act passed, the middle states would arm and that no such usurpation, even for a single day, should be submitted to,” Jefferson explained in a February 15 letter to Virginia Governor James Monroe. Republicans would reluctantly acquiesce if the House legally elected Burr, Jefferson later informed Pennsylvania Governor Thomas McKean, “but in the event of an usurpation, I was decidedly with those who were determined not to permit it because that precedent once set, would be artificially reproduced, and end soon in a dictator.”

Perhaps in response to Republican threats of disunion, on February 9, the House adopted procedural rules that effectively precluded it from passing legislation to designate an interim president. The rules, drafted by a Federalist-dominated committee, gave a literalistic reading to the constitutional provision stating that in the case of a tie between two presidential candidates, the House “shall immediately choose by ballot one of them.” The key proviso in the new rules stated that if the first ballot did not decide the issue, then “the House shall continue to ballot for a President, without interruption by other business, until it shall appear that a President is duly chosen…[and] shall not adjourn until a choice is made.” In effect, members would remain in session until either they elected a president or their terms expired on March 3, whichever occurred first.

Both sides went into the House vote on February 11 with high hopes. The Federalists expected all the Republicans to vote for Jefferson on the first ballot, but believed that some would eventually split off if the balloting continued. Burr had friends in Congress, particularly among Republicans in the closely divided New York and New Jersey delegations. Tennessee’s lone representative, a Republican, also seemed open to persuasion, as did Vermont’s Republican congressman. To win, Burr needed only one or two Republican votes in any three of these four delegations. Rumors swirled of bribes and job offers—but these promises, if made, apparently came from zealous Federalists rather than from Burr himself. In contrast, Jefferson needed only one more Federalist vote from Maryland, Vermont or Delaware to prevail. Republicans believed that he would win on the first ballot.

The entire House and Senate crowded into the ornate Senate chambers at noon to observe the Electoral College vote count. Performing one of his few constitutionally mandated duties as vice president, Jefferson read aloud the 16 state ballots and announced the final totals. As everyone anticipated, Jefferson and Burr had 73 votes each; Adams had 65; Pinckney 64; and John Jay 1. “The votes having been entered on the journals,” the National Intelligencer reported, “the House returned to its own chamber and, with closed doors, proceeded to the ballot.” With Speaker Sedgwick presiding, the voting to break the tie began promptly at 1 p.m.

Breaking the Tie

On the first ballot, Jefferson carried the eight Republican states; Burr took the six Federalist ones; Maryland and Vermont split evenly along party lines and therefore abstained. Members cast 20 more ballots on that first day and through the night, voting typically at one-hour intervals until 8 a.m. Thursday. Nothing changed. They voted again at noon on Thursday, but again reached the same result. Exhausted, the members agreed to recess until 11 a.m. on Friday, February 13. Virginia’s Republican Rep. John Dawson wrote to Madison during the recess: “We are resolv’d never to yield, and sooner hazard everything than to prevent the voice and wishes of the people being carried into effect. I have not closed my eyes for 36 hours.”

The recess did not resolve the impasse. “All stand firm,” Federalist Rep. William Cooper of New York reported following Friday’s vote. “Had Burr done any thing for himself, he would long ere have been President.” The deadlock continued through the weekend and 33 ballots. In a letter to his daughter Maria, Jefferson complained of the “cabal, intrigue, and hatred” of Washington. “I feel a sincere wish indeed to see our government brought back to its republican principles…[so] that when I retire, it may be under full security that we are to continue free and happy.”

The decision came down to Delaware’s lone House member, 33-year-old James Bayard. Bayard was a loyal Federalist but not an embittered partisan, and Hamilton had worked especially hard to convince him to vote for Jefferson. From the outset, Bayard had resolved to cast Delaware’s vote for Jefferson rather than let the election fail and risk disunion. Representatives George Baer and William Craik of Maryland and Lewis Morris of Vermont agreed to follow Bayard’s lead. They would give House Federalists ample time to rally support for Burr—indeed, by some accounts, Bayard even tried to solicit Republican votes for Burr— but if that failed, they would swing the contest to Jefferson.

At a closed party caucus during the weekend recess, Bayard told House Federalists that he intended to abandon Burr. “The clamor was prodigious. The reproaches vehement,” he wrote to a cousin. “We broke up in confusion.” According to some accounts, party leaders asked for added time to see if Burr would offer concessions that could gain him votes. They expected letters from him soon. Accordingly, Bayard voted the party line once more on Monday, and the tally remained the same as the first ballot.

Although Burr’s letters are lost, apparently they arrived that day. In them, Burr “explicitly resigns his pretensions” to the presidency, House Speaker Sedgwick reported sourly, which may have simply meant that Burr refused to offer any concessions. “The gig is therefore up,” Sedgwick concluded.

“Burr has acted a miserable paltry part. The election was in his power,” Bayard informed Delaware’s governor on Monday. As for House Federalists, he added, “We meet again tonight merely to agree upon the mode of surrendering.” The 35th and final ballot for president would occur at noon on Tuesday, February 17.

Ultimately, no Federalists switched sides to vote for Jefferson. In an apparent display of party solidarity and continued opposition to Jefferson, Federalist congressmen from Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island stuck with Burr; the rest simply abstained. This gave the votes of Maryland and Vermont to Jefferson. He carried the election by a margin of 10 votes to four, with Delaware and South Carolina not voting.

Just two weeks before the scheduled inauguration, the election of 1800 finally ended. From start to finish, conflicting hopes for liberty and fears of disorder spurred Americans to an unprecedented level of partisan activity. “I was willing to take Burr,” Bayard wrote on the eve of Jefferson’s inauguration, “but I was enabled soon to discover that he was determined not to shackle himself with Federal[ist] principles.” Forced to take a Republican, Bayard accepted the Virginian, but he did not vote for him.

In spite of his victory, Jefferson was outraged that the Federalists conceded the election by not voting. “We consider this therefore as a declaration of war on the part of this band,” he wrote to Madison after the final House ballot. Indeed, partisanship prevailed to the bitter end and showed no signs of abating. Over the campaign’s extended course, George Washington’s vision of elite, consensus leadership had died, and a popular, two-party republic was born. The tumultuous outcome of the election led to the adoption of the 12th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which enshrined partisan voting by having electors vote separately for president and vice president. There could never be a repeat of the 1800 election—the nation barely survived one such contest.