Many may be aware of the Double V campaign—victory at home and abroad for Black citizens during World War II—but few know of the 26-year-old cafeteria worker at the Aircraft Corps in Wichita, Kansas, who ignited the campaign.

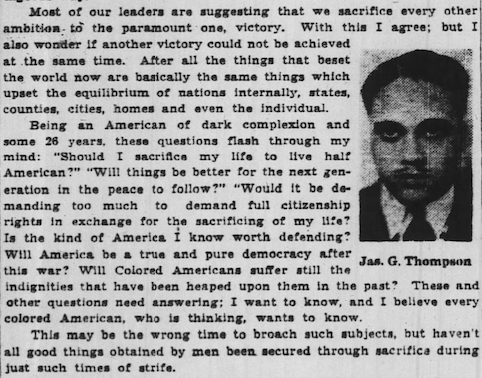

In his letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, a prominent Black newspaper, James G. Thompson pondered the paradox of fighting for equality abroad while facing inequality at home when he penned, “Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?”

Prior to the war, nearly 80 percent of the Black population lived in the South under Jim Crow laws that institutionalized segregation. On the eve of World War II, Blacks carried an unemployment rate twice that of white Americans and a median income that was a third of the average family, according to the National World War II Museum. Between 1918 and 1941 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) recorded at least 544 lynchings of Blacks, although recent estimates have deemed that number to be even higher.

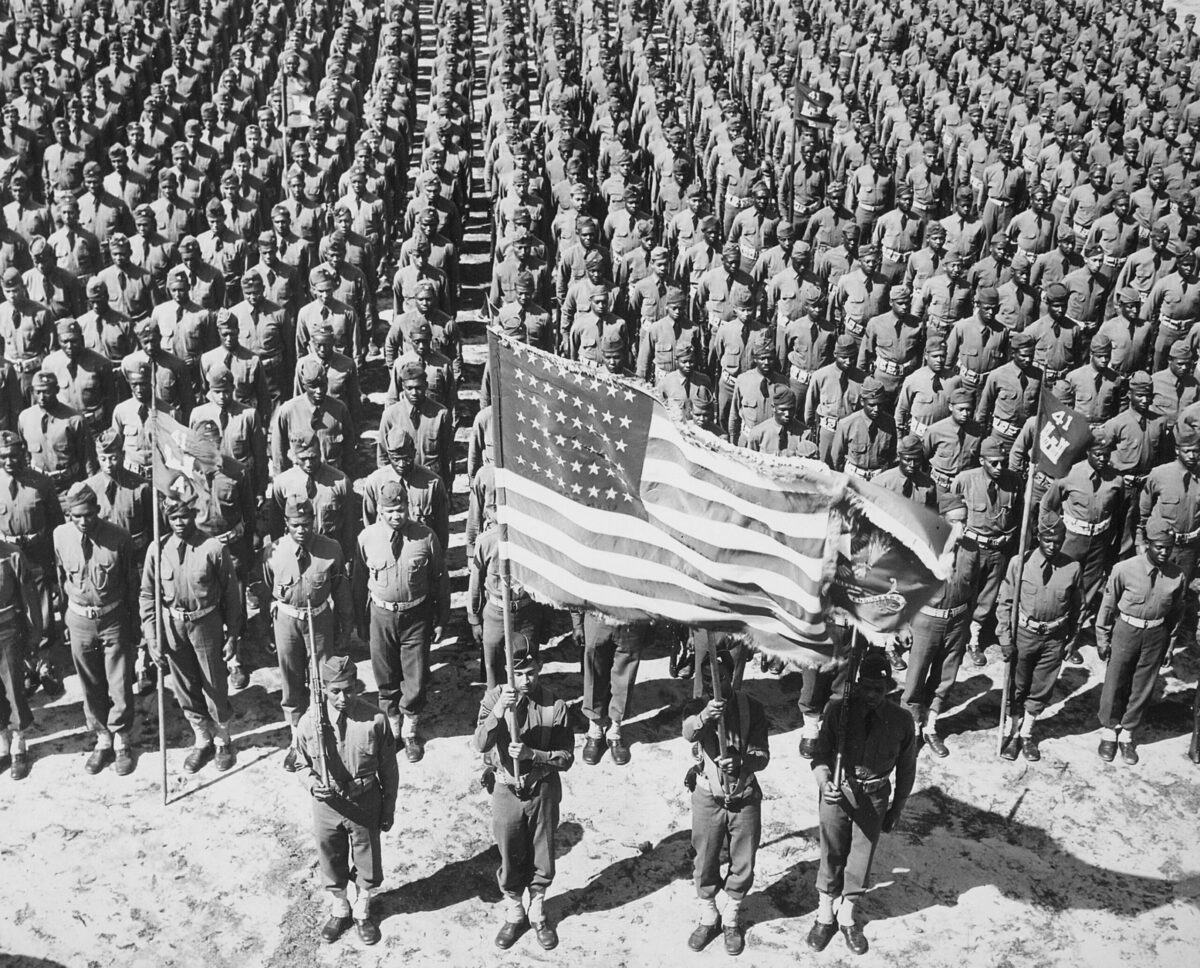

In war time Black men and women faced the duality of fighting against the genocidal Nazi regime, while conversely living through widespread racial violence and discrimination that frequently denied Black citizens their constitutional right to vote.

In his letter, published on January 31, 1942, Thompson implored that “while we keep defense and victory in the forefront that we don’t lose sight of our fight for true democracy at home.” Thompson added, “Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for sacrificing of my life?”

Thompson’s letter tapped into the frustration that many Blacks were experiencing. Historian C.L.R. James later echoed Thompson and proclaimed, “Why should I shed my blood for Roosevelt’s America, for Cotton Ed Smith and Senator Bilbo, for the whole Jim Crow, negro-hating South, for the low-paid, dirty jobs for which negroes have to fight, for the few dollars of relief and the insults, discrimination, police brutality, and perpetual poverty to which negroes are condemned even in the more liberal North?”

Co-opting the “V for Victory” slogan, Thompson suggested that if the “V for victory sign is being displayed prominently in all so-called democratic countries which are fighting for victory over aggression, slavery and tyranny,” then “we colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within.”

Thompson’s letter was not a wild new concept for many Black Americans, but his slogan was memorable and caught the interest of numerous Black newspapers across America.

The Courier, for example, took Thompson’s cue and launched the Double V campaign, demanding social, political, and economic gains. On February 14, 1942 the newspaper printed, “we adopted the Double “V” War Cry—victory over our enemies at home and victory over our enemies on the battlefields abroad. Thus, in our fight for freedoms, we wage a two-pronged attack against our enslavers at home and those abroad who would enslave us. WE HAVE A STAKE IN THIS FIGHT. . . ARE AMERICANS, TOO!”

In June of that year Thompson replaced W.C. Page as the director of the Courier‘s national Double V campaign, and by mid-July the Courier claimed it had recruited 200,000 Double V members—one of the largest Black organizations in America at that time.

The campaign also received considerable support from key white politicians, novelists, and movies stars that included, among others, Wendell Willkie, Thomas Dewey, Ingrid Bergman, and Humphrey Bogart.

Thompson remained with the Courier until he was drafted into service in February 1943, after which time the newspaper largely abandoned its Double V campaign.

And although he faded into historical obscurity, Thompson’s slogan remains a key pillar of the fight for racial equality in the 20th century and a harbinger of the civil rights movement.

“I love America,” he wrote. “[A]nd am willing to die for the America I know will someday become a reality.”