This post contains only a snippet of this article. Please purchase the Autumn 2010 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History to read the entire article.

Before the Civil War, the gentlemen and ladies of Vicksburg had a private refuge. It was a little park, reserved for the best people, on a grassy hilltop near the heart of town. They reached it by a wooden stairway snaking up from street level. The stairway allowed the ladies to ascend with dignity, their hoop skirts unencumbered; the gentlemen were able to keep up their gallant banter without losing a step to a jutting tree root. Slaves followed behind, bearing the picnic baskets. The hilltop was a small plot of mown grass, set with wrought-iron chairs and tables and a spyglass. In the evenings the tables would be swathed in white cloth, and the wine glasses would be brimming. Around the plot were poles drooping with clusters of Chinese lanterns. Sometimes the parties went on long past midnight. By then the lanterns had guttered, and the lights of the town below were out; and with the embers of sunset faded, the sky became an ornate drapery of starlight. The view gave the hilltop its name: It was known as the Sky Parlor.

The Union siege did little to slow Vicksburg’s grand lifestyle—until Federal gunboats made a bold nighttime run down the Mississippi

Vicksburg stood on a high bluff overlooking the Mississippi about 250 miles northwest of New Orleans. The hilltop offered a commanding view of the town, the river, and the surrounding countryside. To the north and east of the Sky Parlor, past the last rooftops of the town, was a vista of jumbled wilderness: thickly forested hills and valleys and sloughs and ravines, romantically veiled in mist, and as wildly lush and overgrown as a tropical jungle. To the south and southeast, the land was flatter and more passable: low hills and wide meadows and—more and more toward midcentury—the ruled fields and parceled expanses of the cotton plantations. To the west, across the Mississippi on the Louisiana shore, was a tangle of swampland. Cutting through the heart of the landscape, between the wilderness and the swamp, was the gigantic river. Vicksburg had been built on the outer bank of a hairpin turn: From the Sky Parlor you could see the river flowing northeast toward town, and then bending sharply around a narrow tongue of swampland, and then flowing away again to the southwest, unfolding its slow, shining arabesques to the horizon.

Vicksburg was a cosmopolitan town. It had always been rich and in the years before the war, it was getting richer. Immense quantities of cotton from the plantations were flowing through the warehouses of Vicksburg Landing, on their way downriver to New Orleans, to the brokers in New York, and out to the consignment markets of Europe. Coming back in were money and bulk goods and fine products from around the world. Vicksburg’s population was only around 4,000, yet its commercial district was able to support a milliner stocking fabrics from Asia; a perfumery with scents from Arabia; a grocery store selling fancy tinned goods from England and France; several deluxe specialty bakers and confectioners; assorted jewelers, custom tailors, and portrait photographers; and a bookstore, Clarke’s Literary Depot, with the latest and raciest novels from New York, London, and Paris.

The coming of the war was not viewed in Vicksburg with much enthusiasm. There was no significant sentiment for abolition in town—but neither was there any for secession. That was in fact a common view among the Mississippi River towns. They lived and died by the free passage of people and cargo up and down the river, from the northern forests to the Gulf; and whatever else the outbreak of the war meant, it was certain to start with river blockades.

The beginning of hostilities between the North and the South in April 1861 proved anticlimactic. The heaviest fighting was back East. The Mississippi blockades did duly appear, at Cairo in the north and at the river mouth in the Gulf, and many of the big steamboat lines did cease running. But the nearby tributaries remained open—most vitally, the Red River, which led west up through Louisiana into Texas—and a glittering boat city still assembled each night on the waters before Vicksburg Landing.

There were also the railroads. The trains from the western states ran to a depot on the Louisiana shore; from there, an armada of ferries shuttled goods and people over the mile-wide water to town. To the east, another line ran through the wilderness country toward the heart of the Confederacy. Over the first months of the war, with more of the ocean and Gulf ports blockaded and battle lines encircling the deep South, the railroad connection at Vicksburg became the city’s main surviving link to the outside world. Jefferson Davis called Vicksburg “the nailhead that holds the South’s two halves together.” Abraham Lincoln told his military commanders: “Vicksburg is the key…. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”

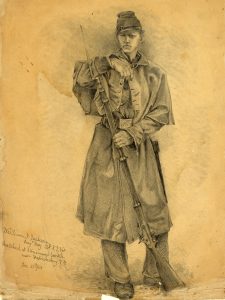

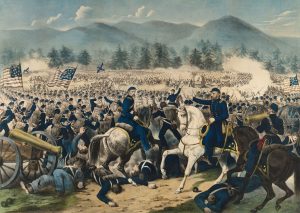

About a year into the war, Confederate forces began arriving in large numbers to defend Vicksburg and keep its railroad lines open. Over the spring and summer of 1862, lines of wagons and troops came winding in from the train depots and the river ferry, and by autumn, the observers at the Sky Parlor saw enormous earthworks being constructed around the town—mazes of trenches and revetments and barricades. At the same time, Yankee forces were gradually occupying the wilderness areas beyond; at night, their countless campfires were brighter than the stars. By the time the Vicksburg campaign was at its height, in the summer of 1863, there were more than 150,000 soldiers contending for the town, and from the Sky Parlor it looked as though there were nothing left in the world but the war.

This post contains only a snippet of this article. Please purchase the Autumn 2010 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History to read the entire article.

Adapted from Wicked River: The Mississippi When It Last Ran Wild, by Lee Sandlin. Copyright ©2010, published by arrangement with Pantheon Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.