Building a rubber airplane or glider that would safely bounce a few times in the event of a crash landing rather than disintegrate on contact—has intrigued aeronautical engineers for many years. The first known attempt to design, build and fly an inflatable rubber glide and then a powered rubber airplane came about after a fatal crash in a Brazilian jungle after World War I. The accident, which resulted in the death of his friend and partner, prompted Taylor McDaniel to think about building an airplane out of inflatable rubber tubes to protect the passengers and pilot in an accident.

Back in the United States, McDaniel worked on his idea for a number of years and finally received a patent for an inflated rubber tube glider that flew twice on January 4, 1931. After making a few control adjustments, an experienced glider pilot and friend of McDaniel’s, Joseph Bergling, flew the glider four more times that same day

On January 11, McDaniel scheduled another test flight and press demonstration for newsreel companies, newspaper reporters and photographers. Towed by a truck, the glider reached an altitude of 100 feet before the pilot experienced control problems. He managed to land safely

McDaniel wanted to cancel the demonstration and take the plane back to his shop to rerig the control system but a photographer who had missed the landing insisted on one more attempt. This time the glider had reached about 80 feet when the pilot lost control. The right wing hit the ground in a near vertical position, collapsing it. When the nose hit next, the wing snapped back to its original configuration, leaving the glider intact. The test pilot suffered only a bruised right heel and a twisted left knee. Close examination of the point of impact revealed that only one wire had been broken in the crash, amounting to about 50 cents worth of damage.

McDaniel’s second construction effort was a birdshaped inflated rubber tube glider mostly put together from his first aircraft before he ran out of money. But when the Great Depression hit the United States in 1931 and 1932, paralyzing the aviation industry, it became next to impossible to raise money for further development. Taylor McDaniel died in 1952 at the age of 61, still convinced his idea for a rubber airplane was a sound concept.

In the Soviet Union, engineers designed, built and flew a glider constructed out of a light rubberized canvas to be used in ferrying supplies inexpensively into Siberia. One large tow plane would pull three loaded gliders to a destination, where they would be cut loose, land and unload. The gliders could then be deflated, packed into a suitcase measuring 39 by 39 by 191⁄2 inches and weighing only 169.4 pounds loaded, then flown back to be reused.

When the initial trial flights proved successful, the head of the project, P.I. Grachowsky, began planning an improved version. But little more is known about the outcome. It apparently never made it into published versions of Soviet military history.

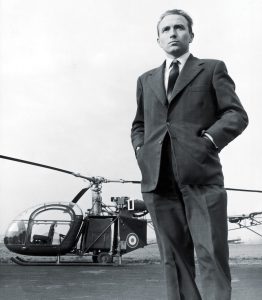

In the early 1950s, the British tried to create an aircraft that could be carried deflated aboard a submarine, in a truck or on a tank, occupy little space and be quickly inflatable for reconnaissance and rescue missions. Using a high-grade rubberized fabric similar to the material in life rafts, Britain’s M.L. Aviation Company began flight-testing an unusual little plane at Farnborough in 1955. Designated the M.L. Light Aircraft Mark 1, it had a huge, rubber-coated fabric inflatable wing with a small, wooden boxlike fuselage slung beneath it, tricycle landing gear and a two-place cockpit. A rear-mounted 60-hp engine powered it.

The 40-foot wing had no internal bracing, relying instead on air pressure to maintain a stiff aerodynamic form. Test pilots reported that the little plane was actually easy to fly and handled well. It needed no more controls than those on the handlebars of a motorcycle. After a flight, the wing could be deflated, rolled up into a bag, packed into the small fuselage and towed away behind a vehicle. In spite of its military and civilian potential, however, the project never went past the early experimental stages.

The most successful variation of the inflatable rubber plane concept was the Inflatoplane, conceived, designed, built and flown by the Goodyear Aircraft Corporation in 1956 from the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company’s Wingfoot Lake Airship Base near Akron Ohio. Designated the GA-33, the Inflatoplane was built and flown in a little over 12 days.

The wing, tail assembly and pilot’s seat were constructed of a new rubberized Airmat fabric developed by Goodyear that consisted of joined layers of inflatable rubber-coated nylon fabric shaped by thousands of nylon threads that gave it one of the highest strength-to-weight ratios of any construction material. The fuselage was made of airship fabric with high-strength, fan-shaped patches of rubberized material providing attachments for struts and metal supports that connected the landing gear and the pilot’s seat to the aircraft. A 40-hp engine mounted on top of the wing in a conventional tractor configuration powered the GA-33. An engine-driven air compressor maintained the low air pressure needed to keep the airplane inflated and rigid.

After successful flight-testing of the GA-33, Goodyear developed a more advanced model designated the GA-447 under the sponsorship of the Office of Naval Research. An extensive evaluation program of the new model followed, including wind tunnel testing at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia.

The test results were so impressive that Goodyear built 10 more Inflatoplanes under the sponsorship of the Army Transportation Corps and the Office of Naval Research. This new model was designated the GA-468. A 60-hp engine replaced the 40-hp version, giving the new model more takeoff power. In addition to improvements in the aircraft structure, a combination wheel, hydro and ski landing gear was developed and incorporated into the GA-468, enabling the Inflatoplane to operate off land, water and snow with no landing gear changes or modifications. The company also developed a parachute-drop pallet and container for the deflated Inflatoplane for use as an airdrop rescue vehicle for pilots downed in hostile territory.

While evaluation continued on the GA-468s, the Army Transportation Corps began development on a two-place Inflatoplane. This last version, designated the GA-466, featured a 60-hp engine, as well as a 60-knot top speed and a 200 nautical mile range.

The Inflatoplane’s primary mission remained serving as a one-or two-man rescue vehicle that could be dropped to downed pilots, broken out of its container, inflated and made airborne within six minutes. Other possible uses included airborne reconnaissance and support for ground operations. The development and test work proved promising, and in August 1959 Goodyear presented plans for a twoplace, more aerodynamically smooth Inflatoplane with a 100-hp engine, an enclosed cockpit and four fuel tanks slung under the wing.

In June 1959, an Army pilot making the final 35 minutes of a required flight put the Inflatoplane through violent maneuvers that were not called for in the program. In consequence, the overstressed wing bent up into the propeller, tearing a hole and releasing the air pressure. Since the inflated fuselage supported the engine mounts, the engine collapsed forward just as the pilot stood up to bail out. He never even managed to open his parachute.

After a number of planes were built, in the fall of 1959, Goodyear ceased production and canceled the project “forever,” according to a company spokesman at the time. Goodyear no longer makes the Airmat fabric used in the construction of the Inflatoplane.

One Inflatoplane was donated to the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., and another to the Franklin Museum in Philadelphia. The first GA-33 prototype Inflatoplane was donated to the Ohio Museum of Flight at the International Airport in Columbus, Ohio. How it got there is a bit of mystery, since the plane was supposed to have been taken to a landfill and buried. Instead, the driver made a detour to Barber Airport in Alliance, Ohio, where the little aircraft was apparently tucked in the back of a hangar until it was donated to the museum.The museum is now closed, and the GA-33 is currently in storage in the Columbus area.

Originally published in the September 2006 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.