On Panel 33E, Row 2 of “the Wall,” the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, is the name Richard Godbout. He was a 19-year-old from Goffstown, New Hampshire, who liked nothing better than riding motorcycles and working on cars. Following in the footsteps of his father, who landed in Normandy during World War II, Godbout enlisted in the Army. He became a tracked vehicle mechanic assigned to the 4th Battalion (Mechanized), 23rd Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, one of the early units to ride to battle sites on a new breed of armored, troop-filled, machine gun-firing vehicle the Viet Cong called the “Green Dragon.”

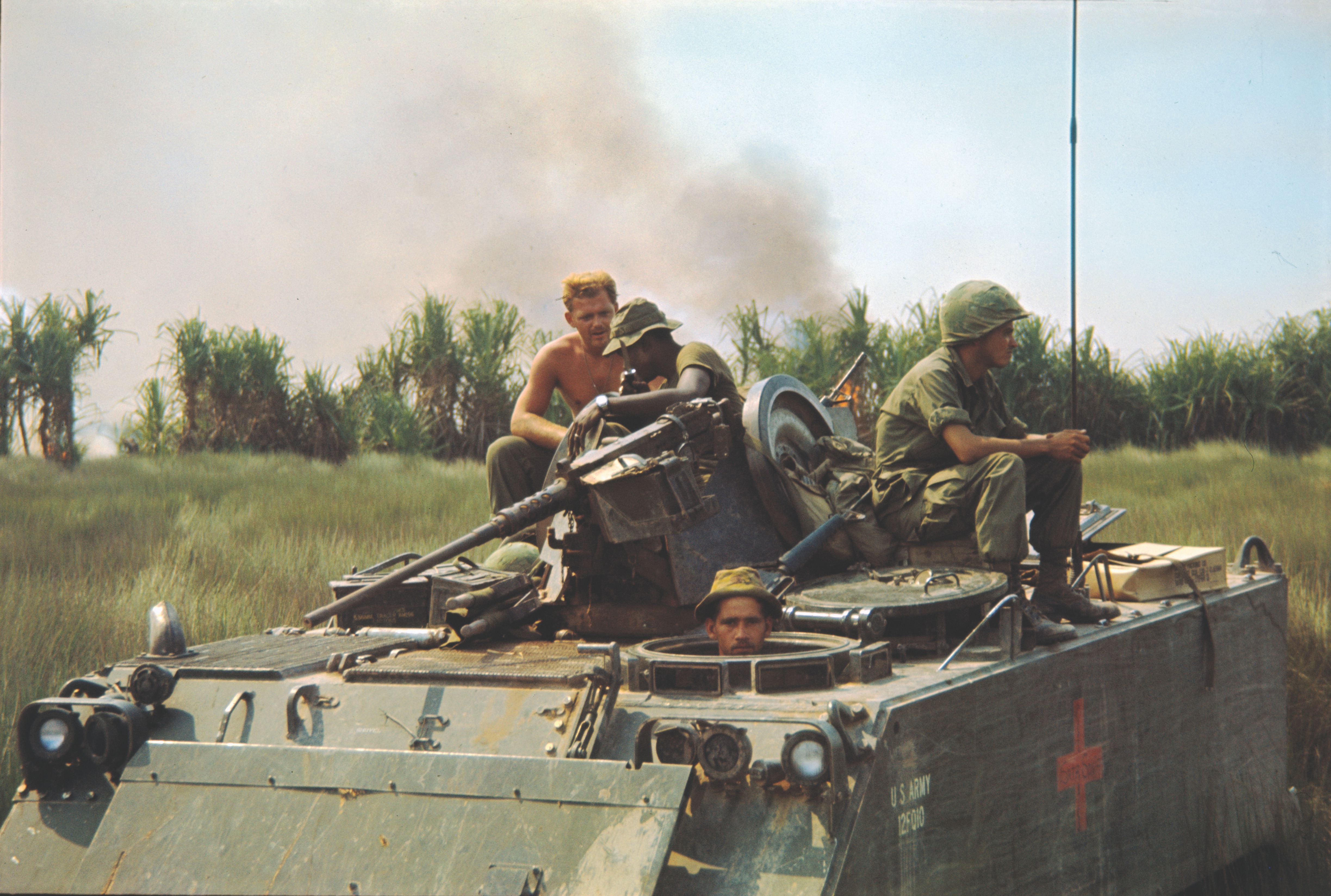

The U.S. Army, more mundanely, designated it the M113 “armored personnel carrier,” which was staffed by a two-man crew—a driver and a commander who also functioned as a machine gunner—and could carry up to 11 other soldiers inside or on top.

Upon arrival in Vietnam on March 3, 1967, Godbout was promoted from private to private first class. By Dec. 30, he had been bumped to specialist 4 and was commanding an M113 assigned to protect a truck convoy on Highway 1 near Saigon. The convoy was only a few miles from base camp when it came under fire.

An Iconic Transport

The M113 personnel carrier, first exposed to combat during the Vietnam War, would join the Huey helicopter as one of the war’s iconic transports, but its legacy extended well beyond the conflict in Indochina. More than 80,000 M113s, built in a series of upgrades, saw action in engagements such as the 1991 Gulf War and the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. They served not only with American forces but with allied nations as well. Although another armored troop carrier, the M2 Bradley, was introduced in 1981, the M113 remained in the U.S. Army’s ranks and is just now being replaced with new “armored multipurpose vehicles.”

The introduction of mechanized units changed the way the war in Vietnam was fought. When the first M113s for the 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry, arrived in January 1967, battalion commander Lt. Col. Louis J. North said the troop carrier would “enhance the mobility and shock action of the battalion,” according to a unit history on the website of the 25th Infantry Division Association. North added, “It will simplify the problems of going into heavily booby-trapped areas and give us the ability to close in on the enemy faster and with greater fire power.”

Production of the M113, developed and manufactured by Food Machinery Corp., began in 1960, and the vehicle started its Army service in 1961. The first units in Vietnam went to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam in 1962. Run by a 209 horsepower Chrysler gas engine, the original vehicle was underpowered and plagued by other weaknesses. The highly flammable fuel was susceptible to firebombing, and the armor—while valuable against small arms fire—offered little protection against heavy weapons. In 1964, an upgraded version, the M113A1, provided a more powerful and reliable 212 horsepower General Motors engine that used diesel fuel, which had the added benefit of being less flammable than gas. The new version also had heavier armor, although land mines were still a real danger.

“Beer Cans”

“Between November 1967 and March 1970, for example, mines accounted for 73 percent of all vehicle losses, including 1,342 M113s,” wrote Col. William T. Nuckols Jr. and Army historian Robert S. Cameron in the January-March 2016 issue of the Army publication Armor. They described the vehicle as “essentially an aluminum box on tracks,” unable to withstand explosive blasts. Some troops who have ridden in M113s called them “beer cans.”

The soldiers inside would place full sandbags on the vehicle floor to provide a little more protection if they hit a mine, recalled Jon Hovde, who drove an M113 in the 4th Battalion’s Company A and wrote a memoir, Left for Dead: A Second Life after Vietnam. Many troops preferred to take their chances riding on top rather than being trapped inside during an explosion from a land mine or rocket-propelled grenade. Outside, the commander, operating the machine gun, was in a particularly vulnerable position, Hovde and others point out, because he was an obvious first target for an enemy RPG.

The standard weapon on the vehicle was an M2 .50-caliber heavy machine gun, but smaller M60 7.62 mm machine guns were also installed on some vehicles. Those machine guns were the M113’s only firepower except for the individual weapons of the soldiers being transported. When they made contact with the enemy, the infantrymen dismounted from the vehicle and fought on foot, and the M113s moved side by side in a defensive position. Machine gunners on the vehicles provided overlapping fire, while the driver stayed ready for the returning fighters and the next movement.

Infantry units weren’t the only ones to use the M113. Cavalry troops mounted them as well. Although the vehicle was the same, the missions were different. The work of the mechanized infantry was much like the mission of the walking, “straight leg,” infantry—maneuver into position to engage the enemy and hold ground—but mechanized infantry could get the job done faster. Cavalrymen in M113s, designated armored cavalry units, were “scouts on steroids,” the eyes and ears of a much larger contingent of heavy armor (tanks).

The 4th Battalion of the 23rd Infantry received its deployment orders for Vietnam on Dec. 17, 1965, and was attached to 25th Infantry Division.

Though trained as a mechanized unit, the Alaska-based battalion shipped out as a leg unit because its M113s weren’t in Vietnam yet. The 4th Battalion reached Vietnam on April 29, 1966, but didn’t get M113s until December when 93 arrived for U.S. forces.

Viet Cong Tunnels

The 25th Infantry Division’s headquarters in Vietnam was about 25 miles northwest of Saigon near the village of Cu Chi, in an area of abandoned French rubber plantations. The camp grew into one of the largest and most fortified U.S. installations in Vietnam, covering 1,500 acres within a 6-mile perimeter. It had a field hospital, supply and ammo depots, and maintenance areas, along with sports fields, swimming pools and a miniature golf course.

Military planners chose Cu Chi as the site for a large camp in part because that location put the combat units stationed there—including the 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry—in position to provide a buffer against possible enemy attacks against the South Vietnamese capital. There was another reason Cu Chi was considered a good spot for a camp: The ground was fairly level, and despite Cu Chi’s closeness to the Mekong Delta, the area was not prone to flooding.

Those characteristics made the terrain ideal not only for a U.S. base but also for Viet Cong tunnels. Cu Chi was the heart of a massive, complex tunnel system. The first tunnels were dug during French colonial rule by the communist-led Viet Minh who were fighting for independence and later formed the Viet Cong to fight the Americans. The Viet Cong expanded the tunnel network—the most effective way to survive massive U.S. firepower. By the time the 4th Battalion arrived, hundreds of miles of tunnels crisscrossed the area, connecting villages stretching from Cambodia to Saigon.

Despite repeated efforts, American forces were never able to destroy all of the tunnel system’s connecting branches. The 25th Infantry Division’s camp was surrounded by hidden tunnel entrances and “spider holes,” camouflage-covered foxholes used for shooting at U.S. troops. It was very dangerous to leave the relative safety of the perimeter, and there were even tunnel entrances within the perimeter walls.

The camp was built on a former peanut plantation. Before the war, Cu Chi had been a vibrant area of intense agriculture. Villagers grew rice and cultivated fruit orchards and nut groves. They raised chickens, pigs and water buffalo. The land at that time was covered by great, dense masses of rubber trees, which had been exploited by French businesses, such as Michelin Rubber Co.

The war turned a vast green area into barren ground, pitted with bomb craters. The size and location of the American camp made it an attractive target for constant mortar and sniper attacks. The 4th Battalion was right in the middle of it. Hovde remembered that Company A alone took 20 percent casualties during his time in Vietnam. Cu Chi was one of the most bombed, shelled, gassed and defoliated areas in the country.

Riding Into Battle

Hovde recalled the wartime conditions within the village: “The poverty there was unspeakable. There were children with no clothes and nothing to eat. There was an orphanage that provided some help to those children who lost their parents to the war, and we often gave a few dollars at payday to help care for the children. Most of their food was taken from them by the VC. When we found untainted rice caches, we would give it back to the people of the villages. The only problem was that as soon as we gave it back the VC would take it again.”

Before the M113 personnel carriers arrived in December 1966, the 4th Battalion operated as a straight leg unit in operations that were primarily search-and-destroy missions, starting with Operation Akron, initiated on May 9, 1966, followed by Operation Wahiawa, beginning May 16, and Operation Makiki, launched on June 3. Other search-and-destroy operations occupied the battalion throughout the summer and fall.

The unit’s actions picked up speed in 1967 as the men rode into battle aboard their new armored vehicles. The 4th Battalion’s first combat as a fully mechanized force occurred during five days in late January 1967 when it participated in the Operation Ala Moana search-and-destroy action. The battalion’s troops killed one Viet Cong, possibly four more and took four prisoners, according to the unit history. Additionally, they destroyed numerous bunkers, foxholes and tunnels, while also seizing 1,800 pounds of rice.

A succession of operations in the coming months kept the 4th Battalion’s M113s constantly on the move, including Operation Junction City (February-May 1967), one of the largest operations of the war against Viet Cong in the Saigon region, and Operation Manhattan (April-June 1967), yet another search-and-destroy mission.

During Operation Manhattan, the 4th Battalion was assigned to engineer units involved with jungle-clearing operations. The 65th Engineer Land Clearing Team employed 30 armored bulldozers to cut back dense jungle in the Boi Loi Woods, a hotbed of VC activity. The 4th Battalion provided security to the engineers, while still conducting searches to ferret out VC units.

The battalion was engaged in other land-clearing operations from June 1967 to early February 1968, this time to eliminate VC hiding places in the old Fil Hol rubber plantation, the tunnel-invested Ho Bo Woods and the Iron Triangle, a triangle-shaped Viet Cong stronghold northwest of Saigon.

Additionally, the 4th Battalion had to keep Highway 1 open. That duty was called “road running.” Numerous supply convoys moved up and down the highway to keep the military machine running. These supply trucks were easy targets for the VC, who often mined the roads and then attacked the vehicles with RPGs and sniper fire. Providing road security was considered “routine,” which the M113 troops discovered was a misnomer.

Godbout, as a mechanic, didn’t have to go on the convoy security mission at the end of December 1967. But after one of the convoy’s M113s broke down, Godbout volunteered to join the mission in the maintenance section’s vehicle, where he acted as commander. The other troops onboard his M113 were regular infantry soldiers.

As the convoy passed a small village about 5 miles from base camp, it came under fire. Godbout, manning the .50-caliber machine gun on his vehicle, took a direct hit from an RPG. The firefight ended when AH-1 Cobra helicopter gunships were called in and laid suppressing fire on the village. But it was too late for Godbout. He and three privates on his M113 were killed. Four others were seriously wounded. Godbout was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star Medal and the rank of sergeant.

The land-clearing operations continued until the communists’ 1968 Tet Offensive, launched at the end of January. Still working in the Ho Bo Woods, the 4th Battalion was pulled from that operation and sent to bolster units defending Saigon. The battalion’s task was to help push Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army units out of the city and surrounding countryside.

On the morning of Feb. 13, 1968, the 4th Battalion rushed in to reinforce the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment, which was engaged in a bitter fight with a battalion of NVA regulars in the village of Ap Cho, just south of Saigon. The 3rd Battalion, with the support of artillery and airstrikes, fought valiantly for 10 days but was unable to gain much ground against the larger and well-supplied enemy. The 4th Battalion began the slow push into Ap Cho, coming under heavy fire from RPG-7s launched from bunkers and spider holes.

By the evening of Feb. 13, still under heavy fire, the 4th Battalion had retaken about one-third of the village. Throughout the night a constant barrage of artillery fire hit the part of the village that remained under enemy control.

The following morning, with the help of the 25th Infantry Division’s M110 self-propelled 8-inch howitzers, the battalion took the rest of the village—a demonstration of a mechanized unit’s effectiveness.

V For Valor

Through March 1968, the 4th Battalion engaged in limited search-and-destroy missions and road sweeps to the north and south of the Cu Chi base camp to keep Highway 1 clear for convoy traffic. During a sweep on March 25, the 19 men and four M113s of a Headquarters Company reconnaissance platoon encountered the 271st VC Regiment as the enemy was preparing to ambush the 4th Battalion’s Company A. Though outnumbered, the recon platoon took on the NVA, facing down RPGs and recoilless rifles. After losing two troop carriers, the recon unit consolidated with Company A—and lost its two remaining M113s in the process.

After hours of fighting, backed by artillery support and airstrikes, U.S. forces turned back the NVA attack. The 4th Battalion had shown again that M113 units were a strong addition to America’s fighting force in Vietnam, although there was a price paid: four M113s lost, six Americans killed and 11 others seriously wounded. Among the valor awards presented to the mech infantrymen were one Distinguished Service Cross, six Silver Stars, 10 Bronze Star Medals with a “V” device for valor and 16 Purple Hearts. The 4th Battalion was credited with 175 communists killed and a large but unknown number of enemy wounded.

From April 1968 until 1971, when the 25th Infantry Division was withdrawn from Vietnam, the 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry, participated in many such missions. Its ability to quickly bring the fight to the enemy won the battalion’s mech infantrymen high praise from both American and South Vietnamese commanders. The unit received two U.S. Army Valorous Unit Awards, the South Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Palm and the South Vietnamese Civic Action Honor Medal, 1st Class.

—Dana Benner writes about history for regional, national and international publications. He holds a bachelor’s degree in U.S. history and Native American culture and a master of education degree in heritage studies. He teaches history, political science and sociology on the university level. Benner served more than 10 years in the U.S. Army.