The mid-1920s was an era marked by aviation challenges, as pilots pushed themselves and their airplanes to the limit on record-breaking flight attempts. In April 1924 four Douglas World Cruiser bi-planes, each with a two-man crew, began an around-the-world trip, taking 175 days to fly almost 24,000 miles, with two of the aircraft completing the circumnavigation. Charles Lindbergh’s May 1927 transatlantic crossing took less than 34 hours, earned him a $25,000 prize and sparked even more interest in challenging, high-risk, over-ocean flights. Three months after Lindbergh’s celebrated flight, Ed Schlee and Bill Brock attempted to fly around the world in an aircraft not much larger than Lindbergh’s Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis—a truly herculean effort.

Edward F. Schlee was born in Detroit in 1887 and with his brothers formed the Wayco Oil Corporation after World War I, eventually owning about 100 gas stations in the metro area. Schlee learned to fly and also owned an air taxi service using Stinson biplanes. His chief pilot was Bill Brock.

Born in 1895, Ohioan William S. Brock had at age 15 traveled to Glenn Curtiss’ flying school in Hammondsport, N.Y. Brock didn’t have the $150 tuition, so Curtiss told him to write home for funds. In the interim, he worked in the kitchen to cover his board. Unknown to Curtiss, Brock took flying lessons from one of the instructors and was soloing in less than a week. It didn’t take long before the instructor said, “Kid, you’re as good as I am.”

Advances in aviation technology were supported by many influential people of the day, including industrialist Henry Ford and his son Edsel. Based in Dearborn, Mich., the Fords sponsored an annual Ford National Reliability Air Tour competition beginning in 1925 to help build the public’s trust in safe air travel. The 1927 tour, held from June 27 to July 12, covered more than 4,000 miles and was won by the same Stinson SM-1 Detroiter that Schlee and Brock would use on their flight. Eddie Stinson, co-founder of Stinson Aircraft, was the pilot, accompanied by Schlee, Schlee’s wife and other passengers. Originally named Miss Wayco after Schlee’s company, the airplane was rechristened Pride of Detroit for the around-the-world attempt.

Like Henry and Edsel Ford, Schlee wanted to prove the reliability of air travel. “Our flight is not a stunt,” he said. “Our main purpose is to demonstrate, dramatically perhaps, but definitely, how practical and serviceable travel by air is today.” An additional goal was to beat the round-the-world record, which at the time was about 28½ days. That effort had been completed in 1926 by Linton Wells and Edward Evans, who used steamships, trains, cars and aircraft for their multi-modal trip. Schlee and Brock planned for their trip to be 100 percent airborne.

Flying around the world with 1920s technology presented significant challenges. The flight would be costly; Wayco’s profits enabled Schlee to provide $100,000 of funding. He also organized the route and identified refueling, maintenance and rest stops. These and other logistics took about a year to organize, dealing with slow communications, language translations and foreign government bureaucracies. The U.S. Navy promised assistance for the Pacific Ocean flight segments.

The SM-1 Detroiter chosen for the journey cost $12,000 off the assembly line and held up to six passengers. It was 33 feet long, had a 45.8-foot wingspan and was powered by a 220-hp Wright J-5 Whirlwind engine that delivered a maximum speed of 122 mph.

The reliable Wright Whirlwind was a real asset for long-distance aviation efforts. The 9-cylinder air-cooled radial weighed less than liquid-cooled engines, allowing extra fuel to be carried. Moreover, its simpler and lighter design meant less could go wrong.

All available cabin space would be used for fuel and oil storage. The instrument panel featured various engine gauges, an airspeed indicator, an altimeter and an earth inductor compass that was more stable than previous devices, making it easier to hold a heading over long periods in the air. No radio was on board.

Concerned that the Detroiter’s loud engine would lull them to sleep, the aviators installed balsa wood in the cabin to muffle the noise. Felt was placed over the gas tank in the fuselage for a bit of comfort during sleep time. Brock, who was short, thought he had sufficient space but that the taller Schlee would have to be a contortionist to fit in that limited area. Auxiliary five-gallon gas cans stored in the cabin added to the cramped conditions.

Plans were made to have an extra engine available in Tokyo in case they needed a replacement. A conversion table with time and distance on the axes and data points for different airspeeds enabled the aviators to estimate distances traveled.

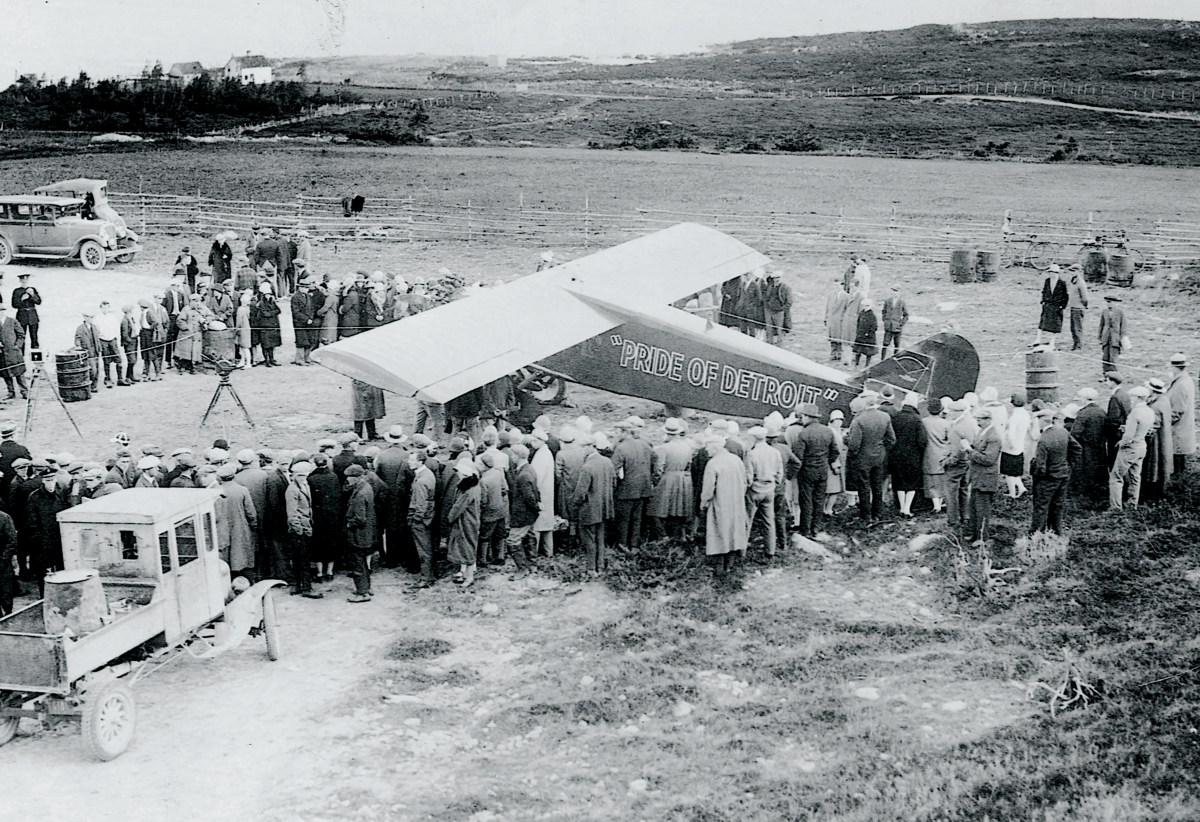

The official start point for the flight would be Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, but there was a problem with that location: It didn’t have an airstrip. To rectify the situation, Stinson’s Fred Koehler traveled to Newfoundland to meet with residents. A location near Crow Hill was selected and city officials approved construction of the airstrip on July 25, 1927, with local citizens and the Newfoundland government making contributions. Beginning in early August, workers cleared an area about 4,000 feet long and 300 feet wide. Extensive manual labor and horse-drawn carts were involved in hauling away rock and other debris from what became the landing field. It was finished shortly before Pride of Detroit arrived.

Schlee and Brock did not appear to be averse to publicity. A July 1927 letter from Warner Advertising to Schlee indicated that press releases about the flight had been sent to local magazines and other publications. Various advertisements promoting their use of Shell gasoline were produced, as Wayco was a Shell distributor.

The aviators left Ford’s Dearborn airfield on August 23, with stops in New York and Maine, before arriving at Harbour Grace (it is unclear why the fliers did not simply designate Dearborn as their official starting point). Brock was confident they could complete the trip in less than 18 days—flying just over 22,000 miles in about 240 air hours, for an average speed of 92 mph. For good measure he brought along a lucky rabbit’s foot.

Schlee and Brock took off from Harbour Grace on August 27, heading to England. They made landfall 24 hours later, but did not know where—England, Wales, Ireland or even France. They dropped a message, weighted down by an orange, to a few onlookers at a small fishing village. When the residents retrieved a large Union Jack flag and waved it at them, the aviators knew they were over England and were able to get their bearings and land at Croydon.

Many miles of flying lay ahead. After leaving England, their stops included Germany, Yugoslavia, Turkey, Iraq, Persia (Iran), Pakistan, India, Burma, Indochina, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Japan. Schlee and Brock overcame numerous challenges, any of which could have resulted in disaster. They could not find Stuttgart’s airfield, which they later learned was 15 miles south of the city, so they opted instead for Munich. In Hong Kong they faced a very risky takeoff, as heavy rain the night before departure left the dirt field in poor condition, especially for a heavily laden aircraft. Maintenance was a constant concern. Once, after a day of flying, Brock spent more than three hours fixing a magneto and adjusting the engine’s tappet rods and rockers.

Neither of the men anticipated getting much rest. “If we get five hours a night, we’ll be satisfied,” said Brock. Food would be whatever was available. Language was not a concern, he said, as “we know the motions and gestures.” While Brock did most of the flying, Schlee calculated drift and pumped gas from reserves into the main tanks.

Weather presented its own set of challenges. The crew dealt with a gale in the eastern Atlantic, heat and dust in southern Persia and severe storms in India and Southeast Asia. Brock later stated that the most dangerous part of the flight was when they encountered a monsoon after leaving Shanghai and “were tossed about unmercifully.” After leaving China, thunderstorms forced them down on Japan’s Kyushu Island. By the time they reached Tokyo on September 13, they had covered more than 12,000 miles in 19 days of travel. But the long Pacific crossing lay ahead.

The transpacific leg would be extraordinarily challenging and risky. After leaving Tokyo, Schlee and Brock would have to find Midway Atoll, about 2,500 miles distant. Midway consists primarily of two small islands, each about two miles long and a half-mile wide, with a maximum elevation of 45 feet—essentially specks of sand in the ocean. After Midway, two more long-haul overwater flights would be required: 1,440 miles to Honolulu and then 2,400 miles to San Francisco.

By this time in 1927, a series of tragedies had the public questioning transoceanic flying. Four days before Schlee and Brock left Newfoundland, Paul Redfern set out from Sea Island, Ga., in a Stinson Detroiter on a flight across the Caribbean Sea to Rio de Janeiro and disappeared in the Amazon jungle (see “Lost Flight to Brazil,” January 2021). Canadian aviators Terrence Tully and James Medcalf attempted a flight from London, Ontario, to London, England, in August. At some point after leaving Newfoundland on September 7, their Detroiter disappeared into the Atlantic. In another tragedy, 10 people lost their lives during the August Dole Air Race from California to Hawaii. The Navy spent millions of dollars searching for these lost fliers, but abandoned the effort due to very limited budgets. As a result, the Navy rescinded its offer to help Schlee and Brock. Navy Secretary Curtis Wilbur said the service would no longer “aid and abet any man who attempted to commit suicide.”

Meanwhile, hundreds of telegrams were sent to the U.S. embassy in Tokyo, pleading for the fliers to call it quits. Press and aviation experts began calling the trip a suicide flight. One telegram in particular, received by the American consul, may have tipped the scale. It was from Schlee’s young children, Rosemarie and Teddy, and read: “Daddy dear please take boat home to us. We miss you.” Schlee’s wife hoped that the fliers would be “sensible and take a Vancouver boat.”

Given the mounting pressure, on September 15 Schlee and Brock decided to call off the remainder of the flight. Heeding Mrs. Schlee’s advice, they took a passenger ship back to the United States, along with the partially disassembled Pride of Detroit. Arriving in San Francisco, Schlee indicated public opinion, as well as the Navy’s change of heart, had influenced their decision: “[A]fter we got about 800 cablegrams from friends and relatives telling us it would be suicidal…we decided to give it up.”

The two aviators had their aircraft reassembled in San Francisco and flew home. Following several stops, they landed in Dearborn on October 4. Friends and family hosted a parade and then a reception that evening, where Schlee collapsed from exhaustion.

The Detroit Free Press summarized their achievement: “Schlee and Brock flew more than halfway around the world with only brief stops, traversing oceans and continents, mountain ranges and deserts, combating fierce storms in strange lands and waters. Their skill and courage never failed them and their machine proved staunch. They demonstrated the practicability of sustained, long-distance flying. All these things combine to make their trip ‘the greatest flight.’”

Schlee and Brock enjoyed a fair amount of celebrity after the flight. In an appearance in Lansing, Mich., their message to attendees was “aviation today is safe, is sane, and practical.” In 1928 Schlee sold the Wayco Oil Corporation and used the proceeds to underwrite ventures such as the Schlee-Brock Aircraft Corporation, which, among other things, sold Lockheed Vegas. The two men undertook various long-distance flights around the country, but nothing compared to their globe-girdling effort.

When the aviation industry fell victim to the Depression, Pride of Detroit was auctioned off in 1931 to satisfy a debt. At one point it was stored in a cow shed. The aircraft was subsequently restored and is now displayed at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn—very close to where Schlee and Brock set out on their round-the-world attempt.

Bill Brock succumbed to cancer in 1932, at age 36. Ed Schlee worked as an aircraft inspector at Packard during World War II and died in 1969. Their flight and those of countless men and women since then have led to tremendous advancements in aviation technology and safety. Round-the-world travel can now be completed in just a couple of days, with minimal stops and with a level of comfort and safety that Schlee and Brock could only have imagined.

Barry Levine works at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn; volunteers at the Yankee Air Museum in Belleville, Mich.; and writes on a variety of aviation and history topics. For further reading, he recommends: Detroitland: A Collection of Movers, Shakers, Lost Souls, and History Makers From Detroit’s Past, by Richard Bak.

This feature originally appeared in the March 2021 issue of Aviation History.