Recommended for you

physical and psychological victories

The first bombs, four 500-pound incendiary clusters, began tumbling down to Tokyo on Saturday, April 18, 1942, at precisely 12:20 p.m. While little is known of Sergeant Fred A. Braemer’s aim, his timing—as well as that of his brother bombardiers who toggled release switches over targets in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kobe, Nagoya, and Osaka that historic day—was nothing short of perfect.

The Doolittle Raid occurred just days after the fall of Bataan in the Philippines, the crowning catastrophe in a string of demoralizing defeats spanning Pearl Harbor to the Dutch East Indies. It delivered a desperately needed booster shot of morale to the American people, as well as an aerial antidote to the virulent “victory disease” that had swept Japan. The bombs caused little physical damage, but effectively exploded the myth of Imperial Japan’s invincibility and prodded its warlords into making strategic missteps that shifted the course of the Pacific War.

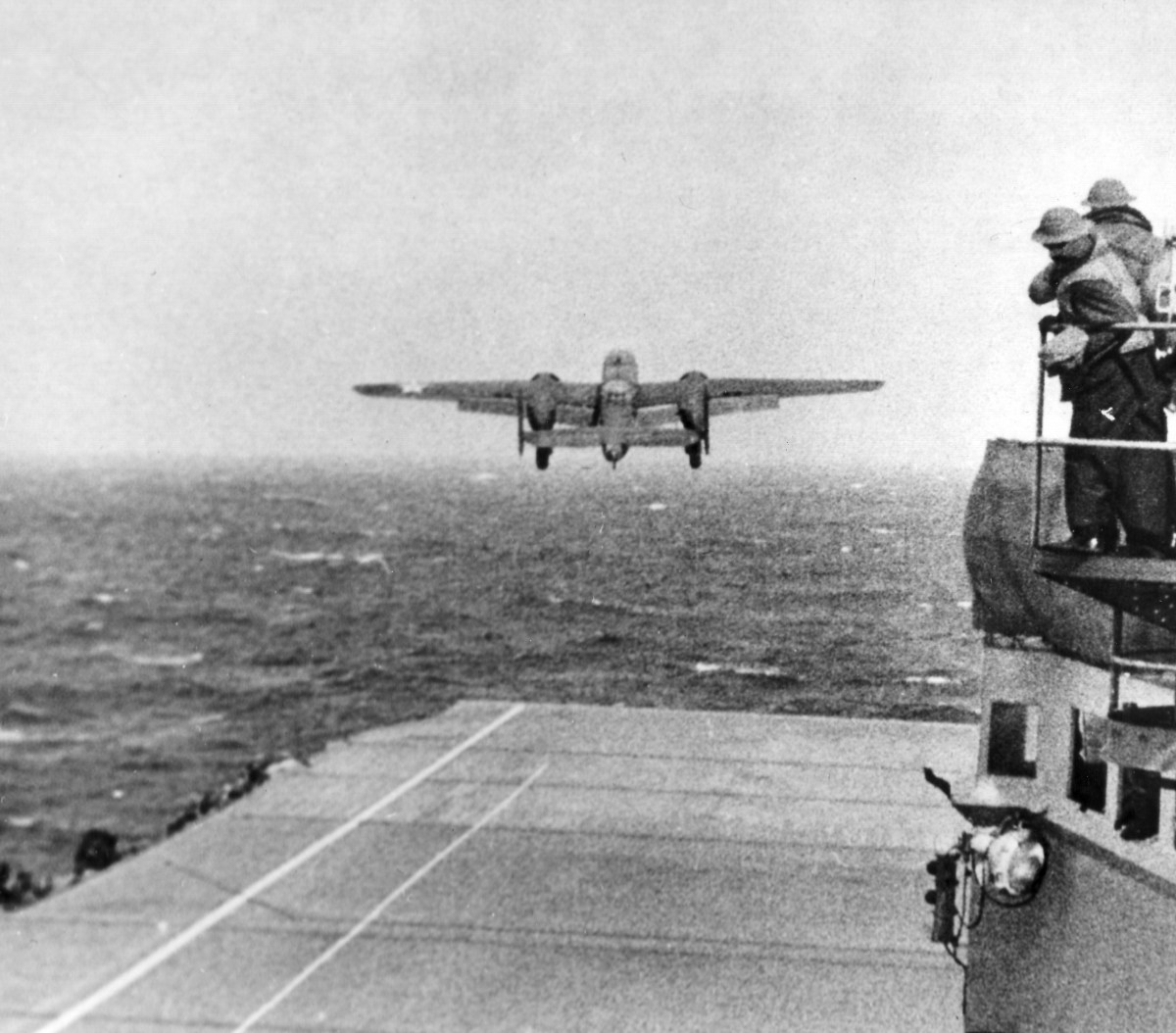

Sixteen U.S. Army B-25 medium bombers, manned by 80 volunteers, powered off the plunging deck of the USS Hornet on that gray, wind-whipped April morning. Five of these heroes lived to see the raid’s 70th anniversary in 2012; four of them attended the commemoration event held at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. There, once the roar of radial engines receded after a flyover of restored B-25s, these last living links to one of the war’s most impossible missions shared the following reflections on the raid, its legacy, their legendary leader, and their extraordinary experiences.

Volunteers for an “extremely hazardous mission”—culled from the 17th Bomb Group, on antisubmarine patrol off the West Coast—arrived at Florida’s Eglin Field in March 1942 for three weeks of intense training and a full introduction to their commander, Lieutenant Colonel James L. Doolittle.

Second Lieutenant Richard E. Cole, 97

Copilot to Doolittle, Crew No. 1, B-25 No. 40-2344

“Colonel Doolittle was one of the nicest, best militarily-formed, educated a person that you’d ever want to meet. A straight shooter, he led by example—particularly the development of teamwork. He stressed the importance of being a team member. Even though he was the team chief, he was a team member. So, to this day, the Raiders don’t like to be singled out.”

Sergeant David J. Thatcher, 91

Engineer-Gunner, Crew No. 7, The Ruptured Duck

“I was in the 95th Squadron—there were four squadrons involved in the raid. We had good flying weather at Eglin, so it enabled us to complete all the training: Flying out over the Gulf of Mexico on the bombing range. Exciting low-level flying, 50 feet off the ground all the time. We didn’t know what we were training for, but morale wasn’t very good for the Allies at the time. The Japanese were advancing through the Pacific and the war in Europe wasn’t going well, either. There was this feeling of urgency. We had a job to do.”

strengthening the hornet’s hive

On April 2, the Hornet and its escort ships put to sea from Alameda, California. The flotilla was joined by the Enterprise-led Task Force 16, under Admiral William “Bull” Halsey. During the tension-filled voyage, the Raiders attended briefings by Doolittle and Lieutenant Commander Steve Jurika, a former naval attaché in Japan, on target selection and escape and evasion. Hornet Captain Marc Mitscher, Doolittle, and Jurika hosted a ceremony that lives on in Raider lore.

Lieutenant Cole: They had the bombs that we were going to use, the high-explosive bombs, and Jurika had gotten some medals from the Japanese when he was in the embassy in Japan and he gave them to Colonel Doolittle, who tied them to the tail of the bombs. It was payback time.

The Klaxon calls to general quarters sounded at 7:44 a.m. on April 18: a Japanese ship had sighted the U.S. strike force. Though the force was still roughly 170 nautical miles from the intended launch point, at 8 a.m. Halsey erred on the side of caution: “Launch planes. To Col. Doolittle and Gallant Crew: Good Luck and God Bless You.” As the Hornet pitched in the tumultuous seas, the B-25s rumbled airborne and began winging toward Japan in staggered formations at wave-top level. They arrived over their targets just after noon, some greeted by antiaircraft fire and enemy planes.

Lieutenant Cole: Everybody thought taking off would be the most difficult thing. It turned out to be one of the easiest. We had plenty of wind and the weather helped; the fact that the ship was moving up and down and around made no difference. When the alert sounded, my first thought was, get to the airplane first. That’s the name of the game as a copilot: get there before the pilot. Otherwise, you get in a one-way conversation! But during the flight Doolittle was very naturally determined and we had no chitchat. Everything was business. When we made landfall, my first impression was that Japan is very nice looking, lots of greenery, well organized. A nice beach. It was like flying over Florida. I had no bad thoughts. I think it’s a waste of time to think about bad things when you can think about good things.

Sergeant Edward J. Saylor, 93

Engineer, Crew No. 15, TNT

“I took a tug of whiskey right after takeoff. It was the first and last time I ever drank on duty. I didn’t expect to survive the mission. But this was the first combat we had ever been in— hadn’t seen any war movies yet, so we didn’t quite know what to be scared of! [Saylor’s crew hit the Kawasaki Aircraft Factory in Nagoya.] The Japanese could have shot us down, but we surprised them. They thought they couldn’t be hit.”

Second Lieutenant Thomas C. Griffin, 96

Navigator, Crew No. 9, Whirling Dervish

“Don’t let the guy tell you he was never afraid, when shells are going by you. [Griffin’s crew encountered perhaps the fiercest antiaircraft fire of the raid during its attack on the Tokyo Gas and Electric Company.] Somehow I went through the whole war and was never wounded by a bullet or piece of flak. But on the raid, was I scared? Well, let’s put it this way: I was concerned!”

Sergeant Thatcher: We took off at about 9 a.m. and reached Japan about noon. Once we got over the beach, six airplanes came toward us. We were flying so low, I don’t think they saw us. Before we reached Tokyo, we could see antiaircraft fire ahead of us. We were flying right over the ground the whole time, but we had to climb to 1,500 feet to drop our bombs. Our target was the Nippon Steel Factory. We had three 500-pound demolition bombs and one 500-pound incendiary cluster. The demolition bombs exploded and then the incendiary cluster spread out over the area and started fires. There were so many good targets, we couldn’t miss.

dark, rainy, and running out of fuel

The raid was only the beginning of the expedition. The crew of one B-25 was interned by the Soviets when they landed in Vladivostok. The other 15 bombers maintained a southwest heading toward secret airfields in China’s Zhejiang Province, but as their fuel-starved engines sputtered dead, the crews were forced to bail out, blindly, into stormy darkness before their B-25s splashed into the China Sea or crashed inland.

Lieutenant Cole: People often ask me, what was the most difficult part of the mission? I’ll tell you: standing in an airplane, with the hatch open, at 9,000 feet, in the middle of a big thunderstorm and so forth, and trying to make a decision about jumping out or not!

Sergeant Saylor: The decision to launch early added extra miles to our trip. We didn’t have enough gas. We landed in the China Sea. Our plane done real good on the water landing, bouncing on top of the waves, and came to a rest. It stayed up for 10 minutes. We got out of the airplane and into the life raft, and everything was going pretty good—and then we pushed off the airplane and the aileron snagged a hole in our life raft and we lost half our inflation. There was a rope attached to it that I hung onto all the way ashore, about a half mile or so. We pretty much came in on the tide.

Sergeant Thatcher: That night, it was dark and rainy. I was in the back of the plane when it crashed and I got knocked unconscious for a while, but that was about all. I realized that the airplane was upside down. We hit the water with our wheels down; the plane nosed over. I was the only one able to walk. I was able to get out and help the other four members of the crew up on shore. [For his efforts in aiding his badly wounded crewmates, Thatcher received the Silver Star.] They had been thrown out through the nose. I went back the next morning to see how much damage was done to the plane. The front, where the bombardier compartment was, it was smashed. If they hadn’t been thrown out, they’d have never got out alive.

Lieutenant Griffin: We didn’t know what we were going to run into or how far we were going to get. It was just a day when we had to improvise as we went along. The thought was, maybe ditch next to a ship and be taken aboard—a friendly ship, hopefully. And then we went west across the China Sea thinking that we might possibly make it to the coast and we did. In fact, we got a good tail wind, which helped us a great deal. We flew down through a canyon and got as much as 300 miles inland before we bailed out. I was hung up in a bamboo tree. I knew we were on the side of a mountain. And rather than get down and stumble around in the dark, I just stayed up there all night. The next morning, I climbed down and made my way down the mountain.

china helped save the day

The weeks ahead were characterized by fear, flight, and the bonds of wartime friendship. Two crews would be captured by the Japanese and subjected to mock trial proceedings. Three Raiders were executed, and one perished in captivity. The majority of the Raiders, however, would live to fight another day, thanks to the aid of Chinese peasants, guerrillas, and government officials. This bravery and loyalty, however, commanded an enormous price: 250,000 Chinese were killed by the Japanese in a retaliatory campaign. The Raiders remain eternally grateful for the help they received.

Sergeant Saylor: With all that training we had, we could have used some survival training, because we had to dodge the Japanese army for a couple of weeks. That was kind of scary. We finally figured out that they were tracking us by our shoes, our footprints. Our shoes had heels; none of the Chinese guerrillas’ shoes did. We were hiding in a Buddhist temple and they tracked us right up to the temple. The Chinese led us back into a cave; the Japanese spent about two hours trying to find us, but after awhile, they gave up. The Chinese did all that they could to help us. In this part of China, there was no transportation, no railroads or anything. We headed for Chungking, which was the provisional capital of China, and here we were on the eastern coast, 2,000 miles away, but we started walking! We ran into a Chinese boy, about 14 or 15 years old; he spoke good English. His family had all been killed in the war. He took up with us and he became our navigator, our interpreter, and our food scrounger. We tried to find him after the war, but couldn’t. I won’t forget him—his name was Pu An.

Sergeant Thatcher: The Chinese underground, the guerrillas, got us out of there. The Chinese had blown up all the roads and highways along the coast to prevent the Japanese from advancing. All we had were trails through the rice paddies. I was walking and the wounded were being carried in sedan chairs. We got into free territory about two days after the crash, but there was no medical help. It took us another day of traveling, about 25 miles, to get to the hospital at Linhai. There we met our first interpreters, a Chinese doctor and his son, who was also a doctor. That was the first medical attention my crewmates received. So by then, the infection had set in and that’s why Ted Lawson had to have his leg amputated. [In 1943 Captain Lawson wrote the earliest firsthand account of the raid, Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, which became a motion picture of the same name in 1944.]

Lieutenant Cole: Colonel Doolittle always said, whatever happens, you can blame it on him. He took that blame. Sergeant Paul Leonard, the crew chief that went to where the airplane crashed, he related his conversation with Doolittle to me and to the rest of the crew. Doolittle was very depressed. He said that he might end up in Leavenworth. Paul said, ‘No, you’re going to be promoted and get the Congressional Medal of Honor. And if you ever have another airplane, I’m going to be your crew chief.’ I remember meeting General He Yangling at a place…I don’t know whether it was his house or not, but he had a telephone. [Yangling was a provincial official in the area of Tianmu Mountain, near Chuchow, who provided invaluable assistance to the downed Americans.] Doolittle was interested with the telephone to try and find out where every airplane was and where every person was. He spent a lot of time on the telephone. Despite his own feelings of failure, he was worried about us, his men, first.

the doolittle raid’s legacy

The raiders remain surprised at the raid’s lasting lure— which is largely attributable to numerous book and film portrayals, such as the recent Pearl Harbor (2001). But they also understand the significance of their singular accomplishment, and hope their story will endure when they’re gone.

Sergeant Thatcher: At the time, we didn’t think it was important at all. We thought it was just another bombing mission. We figured people would forget about it by now!

Lieutenant Griffin: Hollywood has done a fairly good job portraying us, the Doolittle Raid. But it is Hollywood. Of course, they had to have a lot of women, girlfriends, you know, saying goodbye to the boys before they got in the planes. That’s what the ladies like to see. That’s very important. If you don’t do that, you don’t sell many tickets! But the bigger message gets through. I knew even back then when we accomplished the bombing of Tokyo—and those of us that got back into China alive knew— that we had accomplished something special.

Lieutenant Cole: I hope that [future generations] remember that we were just a member of a big force that finally got rid of the Axis. And we did it by everybody doing something, contributing. And people come up to thank me—we are grateful that we had the opportunity to serve!

The Doolittle Raiders plan to meet for their 71st reunion in April 2013 at Fort Walton Beach, Florida, the home of Eglin Air Force Base.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.