IN SAIPAN’S steamy predawn darkness on July 7, 1944, thousands of Japanese attackers hurled themselves at frontline positions held by the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division, unleashing the largest banzai assault of the Pacific War. With total defeat imminent, the Japanese commander on Saipan, Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu Saito, had ordered the attack as an expression of the hallowed word gyokusai—literally meaning a broken jewel or bead, but more broadly referring to choosing an honorable extinction over compromising one’s principles or capitulating to an enemy. Wounded and feeble, Saito himself opted to commit suicide rather than lead the attack. Heedless of the general’s death, about 6,000 of his survivors smashed into the 27th Division line at the appointed hour. The entire front erupted with fire. Multicolored tracer rounds stabbed through the darkness.

Along a narrow spit of front about 1,000 yards wide and manned by only the 105th Infantry Regiment’s 1st and 2nd Battalions, the attackers smashed into the

forward positions and, in many cases, poured through gaps. One of the few American officers to survive the onslaught, Major Edward McCarthy, compared it to a “stampede staged in the old wild west movies. These Japs kept coming and didn’t stop. It didn’t make any difference if you shot one; five more would take his place. The Japs just kept coming and coming. I didn’t think they’d ever stop.” Another survivor, Tech Sergeant John Polikowski, said with wonderment, “It reminded me of a circus ground, or maybe…Yankee Stadium. The crowd just milled out on the field, pushing and shoving and yelling. There were so many of them you could just shut your eyes and pull the trigger on your rifle and you’d be bound to hit three or four with one shot.” Sergeant John Domanowski saw Japanese troops running in single file: “They weren’t in uniform, but had tattered clothes and bandanas on their foreheads. They looked mean. We had to fight to stay alive.” Another infantryman commented bleakly that “the enemy appeared drunk with a thirst to kill.”

The Americans raked them with a storm of machine gun, rifle, mortar, and artillery fire. One company commander, Captain Louis Ackerman, placed a desperate call to Captain Bernard Toth, an artillery observer friend: “For God’s sake, Bernie, get that artillery closer.” Toth replied that he was already placing the shells within 150 yards of the company. He shortened the range to 75 yards, almost right on top of friendly lines. A drumbeat of flares from American ships offshore bathed the area in half-light. Hundreds of Japanese were hit, maimed, shot to pieces, killed instantly, or wounded; some of the wounded simply lay down and killed themselves. “It was a raging, close quarter fight, grenades, bayonets, fire-arms of all descriptions, fists, spears, and even feet were used,” Captain Edmund Love—a combat historian attached to the 27th Division who participated in the fighting—later wrote with a palpable sense of awe.

Still, the Japanese kept coming. Inside a muggy, pyramidal aid station tent just 50 yards behind the 2nd Battalion’s forward foxholes, the acting surgeon—bespectacled, handsome 29-year-old Captain Ben L. Salomon—could not begin to treat all of the many wounded soldiers who lay around him on stretchers or the ground. As the fighting raged a short distance away, even more wounded men crawled, walked, or were carried by litter teams to the tent. Salomon soon had so many patients to treat that he found it necessary to order his aides to move the less seriously wounded outside.

Moments later, he heard a scream. Salomon looked up from a patient just in time to see a Japanese soldier jam his bayonet into a wounded American in the corner of the tent. In an instant, two more enemy soldiers appeared in the tent’s front entrance. Salomon knew that he and his medics were now the last line of protection for the many helpless wounded men under their care.

It was a dire situation—and yet, ironically, Ben Salomon had gone out of his way to put himself in just this sort of position.

GROWING UP IN MILWAUKEE, Wisconsin, as the only child of middle-class Jewish parents, Salomon had aimed from childhood to become a dentist. Athletic, popular with classmates, and the proud recipient of an Eagle Scout badge, Salomon first attended Marquette University before transferring to the University of Southern California (USC), from which he graduated with a degree in dentistry in 1937. True to his dream, he practiced dentistry in Southern California for the next three years—but his life would soon change.

On September 16, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act for males between the ages of 21 and 35, the first-ever peacetime draft in American history. Later that same year, Salomon became among the first to receive a draft notice. Though he had explored the possibility of pursuing a commission as a dental officer—and drew zero interest in that prospect from the army—he instead entered the service in March 1941 as a private with the 102nd Infantry Regiment, 43rd Division. After the onset of war, the unit deployed to remote Canton Island, nearly 2,000 miles south of Hawaii, to guard against the possibility of a Japanese invasion that never came.

In the meantime, Salomon proved himself to be a natural and highly enthusiastic infantry soldier. In regimental competitions, he consistently emerged as the best rifle and pistol marksman. He could fieldstrip and clean weapons blindfolded faster than most men could with their eyes open. He cheerfully took on any task, no matter how onerous. The officers of his regiment uniformly considered him to be the unit’s best enlisted soldier, and Salomon soon became a sergeant in charge of a machine gun section. During off-hours, he performed dentistry for the local population.

In the summer of 1942, the army finally decided to make him a dental officer after all. The War Department sent a letter to his home in Los Angeles, ordering him to report for commissioning. But when Salomon received the forwarded letter in Canton, he refused the commission; he preferred to stay in the infantry. The army would not relent, though—even when Salomon’s commander attempted to get him a commission as an infantry officer. Salomon, then 27, finally bowed to the seemingly inevitable and became a lieutenant in the Army Dental Corps. In March 1943, he was assigned as the dental officer for the 27th Division’s 105th Infantry Regiment in Hawaii—a fairly cushy job that promised little combat action.

Although Salomon enjoyed his new practice, he badly missed life with an infantry company. As the division trained intensively for battle, Salomon kept honing his own combat expertise. In the mornings, he saw patients. But each afternoon, he changed into a field uniform and trained with the rifle company soldiers, again winning all skills competitions. “He wallowed in the dirt and the mud,” Love wrote of him. “He made the long, hot hikes. He fired on the range.” Colonel Leonard Bishop, his regimental commander, called him “the best instructor in infantry tactics we ever had.” Salomon soon earned a promotion to captain. In late May 1944, Captain Salomon and the soldiers of the 27th Infantry Division left Oahu, bound for Saipan in the Marianas, a vital steppingstone on the long road to Japan.

On June 15, 1944, the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions carried out the initial invasion of Saipan against heavy Japanese resistance. Within a couple of days, the 27th Division reinforced the Marines. As a dental officer, Salomon initially had little to do besides hang around regimental headquarters, tend to lightly wounded men, and assist with supply efforts. That changed on June 22 when the 2nd Battalion’s surgeon was badly wounded and evacuated. Salomon eagerly volunteered to replace him. His training as a dentist had prepared him for the rudiments of the job. In combat surgery, practical know-how often mattered more than formal training.

A natural leader, probably because of his down-to-earth demeanor and innate courage, he quickly earned the loyalty of the battalion medics. One of his men, Tech 3 Vincent Donnolo, described him as “a swell guy. He pitched in like one of the boys in the aid-station.” Though Salomon had never attended medical school, he proved himself to be a highly competent combat surgeon. Indeed, he enjoyed his new job so much that he confided to one friend his intention to become a medical doctor after the war. “He told me he wanted to be the best surgeon that ever lived,” the friend later recalled.

SALOMON LOGGED two weeks in combat as the 2nd Battalion’s surgeon, treating and saving an untold number of wounded soldiers. Though no one could ever have been truly prepared for the moment when the Japanese soldiers attacked his aid station on the chaotic morning of July 7, Salomon was better equipped than most. His talents as an infantry soldier, combined with his competitive and protective nature, made him a formidable adversary. He picked up a rifle and, in a squatting position, shot and killed the Japanese soldier who had bayoneted the wounded G.I. Wielding the rifle like a club, Salomon then charged the other two enemy soldiers who had entered the tent. He bashed them so hard that the rifle stock broke. Moving more quickly than the stunned Japanese, he picked up another rifle, shot one man, and stabbed the other to death. Four more enemy attempted to crawl underneath the tent flaps. Salomon stabbed, shot, and even head-butted them.

By now the erstwhile dentist had worked himself into the sort of fury that is common to those who perform valorous deeds in combat. “Captain Salomon was pretty mad,” one of the wounded men who survived the battle later commented. “He was muttering about some sons of bitches not doing their job very well, and he charged out of his tent with his fists doubled up, like he was going to beat hell out of somebody.” Undoubtedly Salomon was frustrated that the frontline companies had not been able to keep the Japanese attackers from reaching his aid station. Outside the tent, though, he saw the true gravity of the situation. Enemy soldiers were overrunning the entire 2nd Battalion front, medics included.

“It was insane to try to hold the line,” Vincent Donnolo—the young medic from Salomon’s unit—later jotted in his diary. “Japs short of firing weapons came upon us with sticks with bayonets attached to them, pointed hard cane stalks, hand grenades, bayonets, sumari [sic] swords, rifle and small arms. Saw Japs mowed down like one would run a scythe…to cut wheat. I fired my carbine into a mass of Japs not a hundred feet away. To my left…I could see hand to hand fighting. The scene was undescribable for the howling of the Japs…and our wounded rent the air.” Donnolo watched in horror as enemy soldiers hacked helpless wounded soldiers to death.

Meanwhile, Captain Salomon returned to the tent. “Everybody’s dead out there,” he told his medics. “I can do these guys [the wounded] more good out there than I can in here. You’re responsible from now on. Get them all back to regiment if you can. I’ll try to hold these bastards off till you get going. See you later.” From inside the tent, one of his men glimpsed him in a kneeling position, firing a rifle at the attackers. Moments later, Salomon took control of a machine gun after the crewmen were killed and began firing steady bursts at the Japanese.

No American ever saw him alive again.

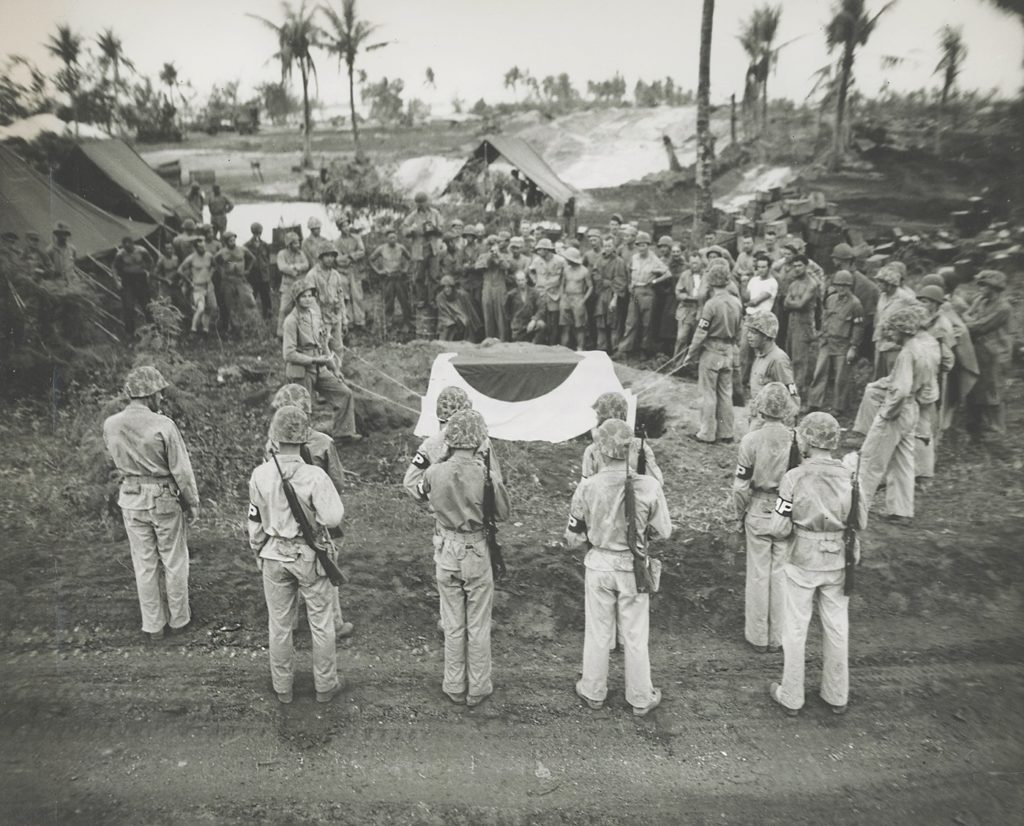

BY THE AFTERNOON OF JULY 7, Saito’s banzai attack had met disaster, destroying most of what remained of his defeated army. The dismembered, decomposing bodies of his men covered northwestern Saipan like a macabre blanket. “The whole area seemed to be a mass of stinking bodies, spilled guts and brains,” one war correspondent wrote. The 27th Division conducted a meticulous count of the remains and claimed a total of 4,311 Japanese dead, including 2,295 in the 1st and 2nd Battalion, 105th Infantry Regiment sectors.

Once counted, the burial parties sprayed milky-colored sodium arsenite solution on the remains to disinfect them and suppress their powerful stench, and then they unceremoniously dumped the corpses into mass graves. “Each sign on top of a mound of earth had the number of dead inscribed such as ‘10, 20, 30, etc’ Japanese dead,” Private Robert Cypher later wrote. In many cases, the Americans used bulldozers to bury the bodies. Tech 3 Donnolo watched several dozers dig hasty holes, repeatedly scoop up mounds of corpses, and dump them into the pit. “What a ghastly sight—the stench was too great for me,” he told his diary. “The dozers just pushed the Japs into the holes with their blades.” He estimated that they buried as many as 400 this way.

The counting parties included Major General George W. Griner Jr., the division commander; Lieutenant Colonel Miles Bidwell, the division personnel officer; Captain Love, the historian; and many others. Outside the 2nd Battalion aid station, they were astounded and aghast at the scene they beheld. They found Captain Salomon’s body, his shirt pulled to his waist, bent over the barrel of a machine gun, its ammunition depleted. Around Salomon’s position, the Americans counted 98 Japanese bodies.

“The area to the front of the weapon was covered with enemy dead, in some instances three and four bodies high,” Chief Warrant Officer Stephen Burns, one of the counters, later testified in a sworn statement. By following the trail of spent cartridges and the pattern of the bodies, Burns, Love, and the others determined that Salomon had probably moved the gun four separate times before running out of ammunition. His body was riddled with bullet and puncture wounds. Love later said he counted 76 bullet holes in addition to the stab wounds. A physician who examined the corpse determined that 24 of the wounds occurred before Salomon’s death.

“There were no witnesses, but it wasn’t hard to put the story together,” Love wrote. “One could easily visualize Ben Salomon, wounded and bleeding, trying to drag that gun a few more feet so that he would have a new field of fire. The blood was on the ground, and the marks plainly indicated how hard it must have been for him, especially in that last move.”

During the months that followed the Saipan battle, historian Love painstakingly reconstructed the action by tracking down and speaking with every survivor from the two 105th Infantry battalions that had borne the brunt of the massive Japanese attack. Unsurprisingly, he never did find anyone who actually witnessed Salomon’s death. He did locate three of Salomon’s men from the aid station who testified to the captain’s actions in the tent and his selflessness in manning the gun so they could evacuate the wounded.

Their stories and the related evidence moved Love to spearhead a Medal of Honor nomination for the valorous dentist, but General Griner quickly squelched it—not from lack of respect for Salomon’s actions, but because he believed that Salomon had violated the Geneva Convention by wielding weapons. In Griner’s view, such an action could, under some circumstances, become scandalous. “I am deeply sorry that I cannot approve the award of this medal…although he richly deserves it,” he wrote apologetically on the nomination papers.

IN POINT OF FACT, Griner was wrong: the 1929 Convention expressly allowed medics to use weapons in defense of themselves or their patients. Nonetheless, the general’s misunderstanding of these rules doomed for decades Salomon’s chances of receiving the nation’s highest military decoration. (See “Long Time Coming,” below.) Not until 2002—after multiple attempts over the years on the part of his advocates—did Salomon finally receive a posthumous Medal of Honor.

On May 1 of that year, at a ceremony in the White House Rose Garden, President George W. Bush presented the medal to Dr. Robert West, a fellow USC dentist and World War II veteran who had led the successful effort for Salomon to receive his recognition. West accepted Salomon’s Medal of Honor on behalf of the USC dental school and the Army Dental Corps, as Salomon’s only next of kin—his father, Ben Salomon Sr.—had died in 1970. In the U.S. Army’s long history, Ben Salomon remains the only dentist to receive the Medal of Honor. Today, that medal is on display at the U.S. Army Medical Department Museum at Texas’s Fort Sam Houston. It rests in a glass case underneath a painted portrait of Captain Salomon—mute and moving testimony to a man of unique talents and extraordinary valor. ✯

Long Time Coming

When Major General George W. Griner Jr. turned down the recommendation for Captain Ben Salomon’s Medal of Honor in fall 1944, he unwittingly set in motion nearly six decades of gross injustice.

Salomon’s exploits began gaining wider recognition shortly after the war, when Captain Edmund Love, the combat historian, prominently mentioned them in a 1946 article he wrote for Infantry Journal about the 27th Infantry Division’s experiences on Saipan. Some two years later, a radio host, Paul Whiteman, read the story on his national program. In his audience that day was Ben Salomon’s father.

The elder Salomon had previously known nothing about how his son died; the U.S. government had not even sent him the captain’s Purple Heart. Ben Salomon Sr. wrote a letter of inquiry to Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson, who asked Love to initiate another effort to award the Medal of Honor to the courageous dentist. Love had great difficulty locating anyone who had witnessed Salomon’s actions and lived through both Saipan and the 27th Infantry Division’s subsequent bloody battle on Okinawa. But by the early 1950s, he had managed to compile a new nomination packet that included three additional affidavits with witness testimony.

In the meantime, though, the Department of Defense had been established; the Korean War had broken out; and, on January 22, 1952, Patterson had died in a plane crash. The army’s hierarchy had little time or inclination to reconsider the case. According to Love, an archivist returned the packet to him, “on the grounds that the statute of limitations for the award of World War II decorations had run out.”

Almost two decades later, in 1969, Dr. John I. Ingle, Dean of the University of Southern California (USC) School of Dentistry and Major General Robert B. Shira, Chief of the Army Dental Corps, undertook a new attempt—the third—to get Salomon the medal. The nomination wound its way through the bureaucracy and made it all the way to the Richard M. Nixon White House, where it inexplicably went no further. Ingle believed that the administration had no wish to awaken memories of banzai attacks when relations with Japan were tense over President Nixon’s attempt to re-establish relations with China.

In the late 1990s, Dr. Robert West, a USC-trained dentist and World War II veteran, took up the cause, working through California Congressman Brad Sherman, in whose district the Salomons had once lived. West and Sherman found an eager ally in Major General Patrick Sculley, who had just become chief of the Army Dental Corps. This time the nomination worked its way successfully through the army’s decorations bureaucracy. In 2001, the Secretary of the Army and the Department of Defense at last approved it, as did President George W. Bush. At the White House ceremony the next May, in recompense for what the president eloquently called a “debt that time has not diminished,” Ben Salomon finally received the Medal of Honor. ✯

This article was published in the October 2020 issue of World War II.