The list of aviation heroes America has taken to heart is endless, from the Wright brothers down to present-day military pilots. The United States has a penchant for adventure-lovers, and has embraced the smiling, clean-living, swashbuckling aviator almost without exception. Even those with perceived character flaws—such as the acerbic Douglas “Wrong-Way” Corrigan, the unapproachable Howard Hughes, the libidinous and bibulous Bert Acosta or the sometimes unverifiable and often aloof Richard Byrd—have been largely accepted with good humor, valued for what they accomplished rather than for how they behaved.

But there have also been a few, a very few, who somehow struck the wrong note and alienated the public, so that they never gained the popularity they obviously sought. These include foreigners, such as Jules Védrines and René Fonck, but among American fliers the most notable is Charles A. Levine.

Levine was born in North Adams, Mass., in 1897, but grew up working at his father’s scrap metal business in Brooklyn. He set up his own company in 1917 and became a millionaire in his early 20s thanks to a salvage contract with the War Department, buying and disposing of spent shell casings. (It was rumored that he was also an “arms czar,” dealing in live munitions.) In the mid-1920s, he ventured into aircraft manufacturing and took flying lessons. Like many before him, he lost his money in aviation, but he also made some worthwhile investments in the industry.

Levine is best known for creating the Columbia Aircraft Corporation and acquiring the beautiful Wright Bellanca WB.2 Columbia, along with the services of its brilliant designer, Giuseppe Bellanca. Columbia, which debuted in 1926, was in many ways a better-looking, better performing aircraft than the Ryan N.Y.P. Spirit of St. Louis, and it had been Charles A. Lindbergh’s first choice for his intended flight across the Atlantic. When Columbia was offered to Lindbergh for a bargain price of $15,000, he hurried to Levine’s luxurious offices on the 46th floor of the Woolworth Building to buy it. The story of Lindy’s disappointment and fury when Levine stipulated he would only sell if he could choose the pilot has been often told. Levine intended to use Clarence Chamberlain, who with Bert Acosta would set an endurance record of 51 hours, 11 minutes and 20 seconds in Columbia on April 12, 1927. Lindbergh, of course, went on to help design and build Ryan’s Spirit of St. Louis, winning the Orteig Prize by flying to Paris from New York on May 20-21, 1927.

Columbia was kept out of that transatlantic race by one of Levine’s frequent legal problems. He had an agreement with Lloyd W. Bertaud to make the flight with Chamberlain, but Bertaud and Levine apparently quarreled. Then, when Levine threatened to replace Bertaud, the latter got an injunction to prevent Columbia from making the transatlantic attempt without him. Bertaud, airmail pilot James D. Hill and Philip Payne would die on September 7, 1927, in an ill-fated transatlantic effort with the Fokker F.VIIA Old Glory.

Disappointed but not discouraged by Lindbergh’s success, Levine determined to use Columbia’s greater endurance to upstage Lindy by flying from New York to Berlin. He further enticed media attention by declining to name the “mystery passenger” who would accompany Chamberlain on the flight. On June 4, 1927, Levine resolved the mystery by slipping into the seat next to Chamberlain, who then revved the engine and took off. It had apparently been kept a very close secret; Levine’s wife fainted when she realized what had happened.

As irritating as Levine could be on occasion, he did not lack courage. He occasionally spelled Chamberlain at the controls as they flew nonstop to Eisleben, Germany, about 100 miles southwest of Berlin, covering the 3,911 miles in 43 hours, 49 minutes and 33 seconds. After being congratulated by the locals, the intrepid pair drank some coffee, put 20 gallons of gasoline into their nearly empty tanks and took off again, heading once more for Berlin. This time they ended up at Kottbus, later the home of a Focke Wulf factory. A third attempt brought them to Tempelhof Airport, where a crowd of some 10,000 cheering Germans greeted them. When Levine and Chamberlain returned home, they were honored with a ticker-tape parade down Fifth Avenue.

President Calvin Coolidge received Chamberlain at the White House, but ignored Levine. The Jewish community—in the midst of celebrating Levine in song and story as its own first hero of the air—was rightfully outraged. His achievement is commemorated in a Web site, http://www. yiddishradioproject.org/exhibits/levine, where some of the songs written in his honor may also be heard.

As for Chamberlain, he was as well liked as Levine was disliked. A modest man with a genial personality and great flying skills, he would go on to an influential career in aviation, setting additional records, acting as a consultant to the industry and forming his own companies, one of which purchased twin-engine Curtiss Condor biplane transports to use in barnstorming exhibitions.

Although the peak of Levine’s personal fame had passed by 1928, he had yet to render his greatest service to American aviation. While in Europe, he had met Alexander Kartveli, Armand Thiebolt and Edmund Chagniard, who tried to sell him on the merits of a seven-engine, 100,000-pound gross weight airliner that would be intended to carry passengers nonstop from New York to Paris. Their grandiose plan was a little much even for the flamboyant Levine. But seeing how capable the three men were, he decided to bring them to the United States to be part of his new firm, Columbia Air Lines Inc.

Kartveli would gain fame thanks to his work for Alexander de Seversky and later Republic Aviation, while Thiebolt would do equally well for Fokker, General Aviation and Fairchild. Chagniard would have a hand in the creation of one of Levine’s own aircraft. Had Levine not seen their potential, there might never have been a Republic P-47 or a Fairchild C-119.

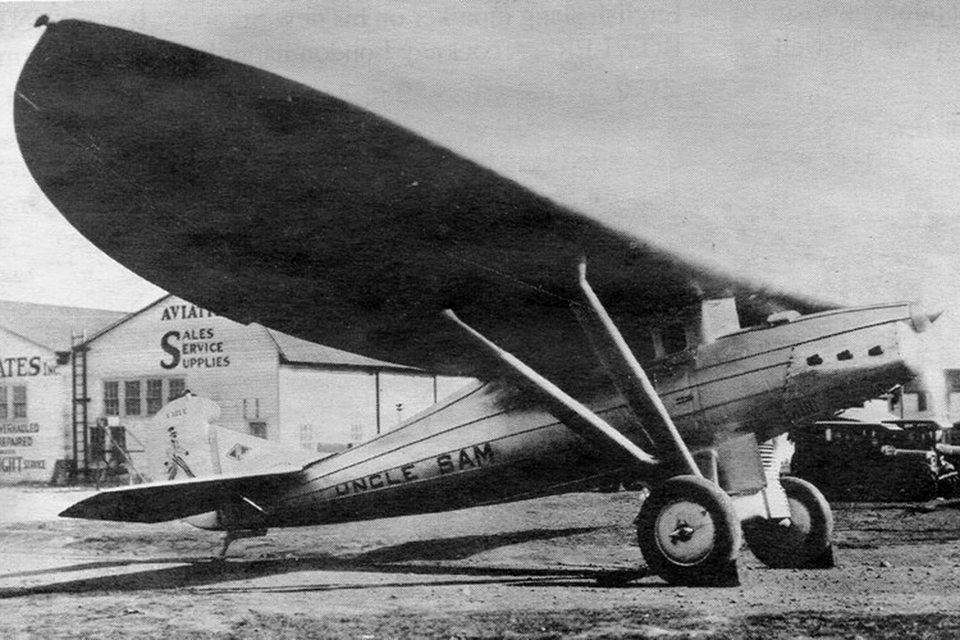

Levine’s renamed firm, Columbia Air Liners, would create only three aircraft, one of them the joint product of the three engineers he had brought over after his European sojourn. The first of these was Uncle Sam, a handsome high-wing, all-metal monoplane, woefully underpowered by a Packard 2A-1500 engine. Tremendously overweight, Uncle Sam cost Levine, whose fortunes were sinking in other areas as well, about $250,000. First tested on April 18, 1929, by Roger Q. Williams, Uncle Sam was flown fewer than 20 times (including one flight by Charles “Speed” Holman) before being retired to the Columbia hangar. After the Uncle Sam fiasco, Kartveli, Thiebolt and Chagniard all departed for new careers.

The firm’s next venture was the Triad. Designed by Lee Worley, the Triad drew heavily on the aerodynamics of Columbia. The new design’s claim to fame was that with relatively little effort it could be converted from a landplane to a seaplane to an “amphibion,” as the firm misspelled it. No performance figures were released on the aircraft, which in itself tells us quite a bit about the design and construction process at Columbia. Although records are not specific, it probably first flew in late 1929 or early 1930.

The Triad was a conventional strut braced, high-wing monoplane, finished in green and cream. The only unusual feature of the landplane version was the Loening amphibianlike placement of the 225-hp Wright J5 Whirlwind engine high on the fuselage nose. To change it from a seaplane to a landplane, the aircraft was placed on jacks, the float and stabilizing wing floats were removed and the landing gear was installed. The amphibian version reportedly had a hydraulically operated retractable gear, but existing photographs do not reveal how this operated. It’s possible that the amphibian version may never have gone beyond the brochure stage.

Whatever his faults or the personality flaws he might have had, Levine was good at promotional brochures. In this case the sales pamphlet was designed in the same green and cream colors as the aircraft, and he lyrically asked prospective purchasers to consider themselves “Cruising into an infinity of sky—luxuriously, complacently, speedily—to land in a shaded lagoon of an island in the sea, a wide brown field, a lazy river or the great gray glistening strips of a modern airport….This is the aim and the achievement of the new Columbia ‘Triad’ Amphibion….Cruising, as an amphibian, like a great blue goose….Circling as a seaplane, with the grace of a gull ….Fleeing, as a land-plane, with a pigeon’s swiftness.” (In retrospect, we might deduce that the final line has some Freudian significance in the use of the words “fleeing” and “pigeon,” since Levine spent much of the rest of his life fleeing from pigeons with whom he had done business.)

Two Triads were built and subsequently stored in the same hangar where Uncle Sam was already gathering dust. Levine was soon 14 months behind on the hangar rental, and Roosevelt Field’s management obtained a court order authorizing it to sell the hangar’s contents.

An auction was held on January 19, 1931, with Uncle Sam going for $750, and the two Triads and other equipment adding only $2,160 more. These bids were disallowed, however, and a speculative bid by Paul Gillespie, then a director of the Roosevelt Flying School, bought everything for $3,000. Only three weeks later, however, a fire destroyed the wooden hangars at Roosevelt Field, and all three of the Columbia aircraft within.

Life did not get any better for Levine after that. His businesses as well as his marriage disintegrated, and the onetime millionaire disappeared from view. He did receive some brief notoriety in 1934, after he was found unconscious in the kitchen of a friend’s house. In 1937 the erstwhile headliner was back in the news, this time in connection with a Federal charge of smuggling into the United States some 5,000 pounds of tungsten powder from Canada. He was arrested and found guilty, fined $500 and spent 18 months in jail.

Levine fell into trouble on a different border in 1942, this time in what would now be considered a worthy cause. He was charged with assisting in the illegal entry to the United States of an alien, Edward Schinek, a German Jew fleeing from Adolf Hitler’s Germany, who had previously been denied entrance into the country.

Levine worked with Schinek’s son, Peter Joseph Walter, to smuggle the émigré into Laredo, Texas, from Mexico. Walter illegally obtained the birth certificate of an American citizen, Edward Siegel. Levine supplied a letter stating that Schinek (posing as Siegel) was an American businessman and an old acquaintance of his. Schinek’s wife was later smuggled into the United States at San Ysidro, Calif., carried inside a false gasoline tank built into a car.

This time Levine was found guilty, fined $500 and given a 150-day suspended sentence. He could not come up with the fine money, however, and once again disappeared from view.

In 1952 the Federal Bureau of Investigation reopened his case, for the elusive Levine had not paid his fine for smuggling tungsten 15 years earlier. A tip-off from a former business associate enabled the FBI to locate the one-time aircraft executive in April 1956. Levine, looking shabby and ill-kempt in court, was unable to pay anything toward his fine. The case was finally closed in 1958.

At some point in his downward spiral, Levine met a woman who undertook to support him for most of his remaining years— and he did have many years remaining. He had a brief reunion with his daughter at one point, but later returned to the care of that woman, who had apparently picked him up off the street. When Levine died on December 18, 1991, at age 94, his obituaries in the New York papers noted that he had been the first transatlantic air passenger.

For all his personal woes, Charles A. Levine made a positive contribution to aviation. First came the brief shot in the arm he provided with his record-setting flight as a transatlantic passenger in Columbia. Next he did the United States an important favor when he brought it two top flight engineers, Kartveli and Thiebolt. Finally, after the firm he founded had passed out of his control but was under new management as Columbia Aircraft, it went on to build Grumman J2F amphibians for the U.S. Navy during World War II.

The firm also created one monoplane version of that basic design, the Columbia XJL-1, which may still be seen at the Pima Air Museum at Tucson, Ariz. Columbia Aircraft was acquired by Commonwealth Aircraft in 1946.

Originally published in the January 2006 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.