When the Douglas B-18 bomber joined antisubmarine warfare patrols, an old dog learned a new trick.

On August 22, 1942, Oberleutnant-zur-See Ludwig Forster was enjoying a brief respite from torpedoing Allied merchant ships in the Caribbean Sea when U-654’s lookout spotted an aircraft approaching. Forster, who promptly ordered a crash dive, had no clue that the aircraft that was attacking his submarine would one day be derided as obsolete and incapable of combat operations. All Forster knew was that the Douglas B-18 bomber was a threat to his ship.

Captain P.A. Koenig’s B-18 swooped down, dropping all four of its 600-pound depth charges on the German submarine. U-654 was torn apart by the subsequent explosion, making it the first victim of B-18 antisubmarine warfare (ASW) patrols.

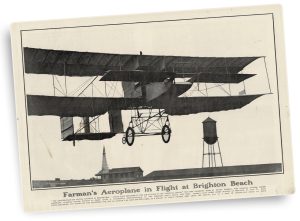

The origins of the B-18 date back to 1934, when the U.S. Army Air Corps (USAAC) issued a requirement to improve the range of its Martin B-10 bomber force. Three companies responded to a request for an aircraft that could carry a ton of bombs at 200 mph over a distance of 2,000 miles. Flight testing on the new designs began in July 1935.

Boeing offered its Model 299, a four-engine bomber with many advanced features that was capable of outperforming its twin-engine competitors. USAAC generals were very impressed and wanted to see the big plane in production, but the Army General Staff deemed it too expensive and signed off on the procurement of only 13 developmental aircraft, designating them YB-17 Flying Fortresses.

Martin responded with an improved version of the B-10 bomber, but its inferior performance left Douglas’ Model DB-1 the winner of the competition. Designated the B-18 Bolo, it was based on Douglas’ successful DC-2 commercial airliner. The Army ordered 177 aircraft, and Douglas delivered the first production B-18, equipped with 930-hp Wright Cyclone engines, to Wright Field on February 23, 1937. The 2nd, 5th, 7th and 19th Heavy Bombardment groups received shipments of the new bomber and began putting them to the test.

The greatest drawback to the B-18 design was the cramped bombardier position. Douglas redesigned the nose of the aircraft, creating the B-18A’s distinctive profile. Douglas also upgraded the engines to 1,000-hp Wright Cyclones, equipped with fully feathering propellers. Those changes were implemented in April 1938, beginning with the 134th aircraft, and the USAAC ordered an additional 211 aircraft. Douglas had delivered a total of 217 B-18As by January 1940.

The B-18s participated in U.S. Army airlift as well as airborne maneuvers. Experiments with the new aircraft included powered turrets, airborne radar and 75mm cannon tests. The latter experiment led to the production of the North American B-25G and H models with nose-mounted cannons.

With war imminent in Europe, Douglas hoped to sell large numbers of B-18s to Great Britain, but the firm only managed to sign a 20-plane contract with the Royal Canadian Air Force. The Digby Mark I entered RCAF service with No. 10 Squadron (Bomber Reconnaissance).

Despite its strong points, the Bolo was totally outclassed by European aircraft of 1939. In an effort to keep the production program alive, Douglas proposed a radical redesign, which the USAAC accepted without a prototype. The last 38 aircraft of the contract were delivered as B-23 Dragons—faster and incorporating the first tail turret on a USAAC bomber. Delivered in July 1939, they went into immediate service with the 17th Bombardment Group.

this article first appeared in AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Facebook @AviationHistory | Twitter @AviationHistMag

The Douglas bombers were totally unsuited to long-range bombing missions in hostile airspace. The Army Air Corps was expanding so fast, however, that factories could not keep up with the demand for new bombers. B-18s and B-18As still equipped 34 bombardment and nine reconnaissance squadrons at the time of the United States’ entry into the war in December 1941. They were serving with every numbered major command, and they were the most numerous bomber deployed overseas. The Army hoped the B-18 could fill the gap until more suitable aircraft became available in quantity.

When the German U-boats began patrolling North American waters, RCAF Digbys were the first Douglas bombers to see action. Number 10 Squadron moved to Nova Scotia and began ASW patrols. A Digby piloted by Squadron Leader C.L. Annis made the first RCAF attack on a U-boat on October 25, 1941. During the course of the Digbys’ combat service with the RCAF, they conducted 11 attacks on U-boats and destroyed one sub: U-520, sunk east of Newfoundland by another of No. 10 Squadron’s planes on October 30, 1942.

USAAC B-18s did not have long to wait for action. On December 7, 1941, the 5th and 11th Bombardment groups at Hickam Field, Hawaii, had 39 bombers, 33 of which were B-18s. The 28th Bombardment Squadron at Clark Field in the Philippines had another 12 Bolos. Many B-18s were among the aircraft destroyed at Hickam and Clark fields during the initial Japanese attacks.

The surviving B-18s in Hawaii, as well as squadrons in Alaska, participated in armed reconnaissance patrols after the attack. When Midway Atoll was threatened in May 1942, Hawaii-based B-17s and B-18s joined U.S. Navy patrol bombers searching for the Japanese Combined Fleet. Not until November 1942 were enough B-17s available to replace the B-18s in the Pacific.

The surviving B-18s in the Philippines were used as armed transports between Mindanao and Luzon. When resistance finally collapsed there, many USAAC pursuit pilots were evacuated to Australia in B-18s. Bolos in the Far East continued to serve as armed transports through the Gilbert Islands and Marshall Islands campaigns.

When the United States entered the war, demands for new bombers far outpaced American industrial capability. The Bolo continued to serve in bombardment squadrons based in the United States and the Caribbean. In these theaters, the B-18s found a new role as an ASW bomber. By the end of 1941, four B-18 squadrons from the East Coast and six from the West Coast, as well as all 15 Caribbean squadrons, had been dedicated to ASW patrols. The number of B-18 squadrons flying those patrols varied through October 1942 as the ASW forces were realigned.

With America in the war, Britain shared some of the technological innovations it was employing against the German U-boats. The U.S. Army took advantage of this technology and upgraded 122 Bolos to B-18Bs and B-18Cs. The B-18B replaced the glazed bombardier’s position with a radome containing an SCR-517-T-4 air-to-surface vessel radar. Some modified Bolos were also equipped with a Mark IV magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) installed in a boom extending from the tail of the aircraft. The MAD system notified electronics operators when they passed over a large metallic object, even if it was submerged. As a Bolo passed over a submarine, a set of retro bomb racks could use a small rocket charge to propel a depth charge rearward toward the target, offsetting the forward momentum of the aircraft.

The U.S. Army Air Forces (as it was redesignated in June 1941) was also developing new tactics to take advantage of its ASW capability. The Eastern Defense Command formed the 1st Sea-Search Attack Group in September 1942 with B-18Bs and other aircraft, and the Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command (AAFAC) was activated on October 15. Of the eight squadrons initially assigned to the AAFAC, five were flying Bolos.

Douglas bombers claimed four U-boats and a whale (much to the embarrassment of Captain N.D. Meadowcroft and his crew) during the war. The 45th Bombardment Squadron recorded the first B-18 kill on August 22, 1942, when Captain Koenig sank U-654. Then a Lieutenant Lehti of the 99th Bombardment Squadron sank U-512 on October 2, 1942. The RCAF Digbys got the next kill on October 30, when Flight Officer D.F. Raymes of No. 10 Squadron sank U-520. The final kill by a B-18 occurred on August 8, 1943, when Lieutenant Milton Wiederold of the 10th Bombardment Squadron, piloting B-18B Robust Man, assisted U.S. Navy Martin PBM Mariner patrol bombers in sinking U-615.

B-18s contributed to the safety of shipping throughout the Western Hemisphere. They patrolled from Nova Scotia to Brazil, where the Força Aérea Brasileira (FAB) operated two Bolos modified to B-18B standards and provided under the Lend-Lease program.

Digbys occasionally served in roles beyond ASW patrols. Group Captain Roy Holmes Foss and his crew were conducting Atlantic ice patrols in their Digby on March 11, 1942, for example, when they spotted a different target. Foss’ crew sprang into action photographing the target and noting its location. As soon as they returned to base, Foss contacted the sealing fleet. He and his crew had found the main seal herd, and their report helped make that year’s hunt very productive.

The AAFAC had seven Bolo squadrons by the end of November 1942, when those units were redesignated antisubmarine squadrons. At that point the USAAF was committing its four-engine bombers to strategic bombing operations as fast as they could be built, and the B-18s had to labor on. By mid-1943, a couple of antisubmarine squadrons were able to trade their Bolos for Consolidated B-24 Liberators, but the transition was proceeding slowly. The B-18 might have served in ASW roles throughout the war had antisubmarine warfare not undergone a sudden change.

In August 1943, the U.S. Army and Navy came to an unprecedented agreement. Before World War II, Congress had mandated that the Navy was not permitted to operate land-based combat aircraft. During the war, these rules were gradually modified. The Navy sought greater control over all aspects of naval warfare, and the Army needed all its units for combat operations in Europe and the Pacific. In mid-1943, the Army agreed to turn over all ASW operations to the Navy. The USAAF disbanded the AAFAC and turned most of the modified B-24s over to the Navy. The Navy supplemented those aircraft with new Consolidated PB4Y Liberators, at which point it had no need for the B-18s.

The USAAF B-18 squadrons, both in the AAFAC and the Sixth Air Force, were reequipped with the new Boeing B-29 bombers and prepared for transfer to the Pacific theater beginning in November 1943. The Bolo’s combat career with the USAAF had come to a close, but these aircraft joined B-23s in noncombat roles. By the end of 1943, only the FAB’s B-18s were still conducting combat patrols.

After the war, many Bolos and Dragons were sold to commercial operators who used them for cargo hauling or crop spraying, and some of the surplus B-23s were refitted as corporate aircraft, equipped with a new, longer metal nose, full washroom facilities and accommodations for 12 passengers in two compartments. Civil Dragons were still flying in the late 1970s, and several Bolos were flying into the 1980s.

Five Bolos and four Dragons have been preserved and are on display to the public. Castle Air Museum in California has an original B-18 (serial no. 37-029) and a B-23 (39-045). The National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, has a B-18A (37-489) and a B-23 (39-037). Another B-18A (39-025) can be seen at Wings Over the Rockies Museum (aka Cannon AFB Museum) in Denver, Colo. McChord Air Museum in Washington has a B-18B (37-505) and a B-23 (39-036). Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, Ariz., also has a B-18B (38-593) and a B-23 (39-051).