The odd Kansas foursome ran an inn that proved deadly to travelers for years before suspicious neighbors did some digging in the family’s apple orchard and learned the gruesome facts

With hand to forehead, Ed York shaded his eyes, scanning the Benders’ orchard. “Boys!” he yelled as his gaze settled on a rectangular depression in the earth among the immature fruit trees. “I see graves!”

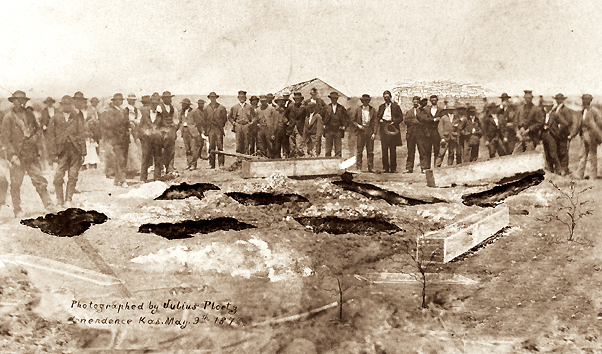

In the spring of 1873 a community of southeastern Kansans descended on the Bender homestead with all the tools necessary for planting. George Mortimer, harnessed to his harrow and horse, plowed furrows through the soft earth as others worked their spades and shovels. This was no spring planting, though. It was a harvest—an unusual harvest, not one of good spirit in which neighbors converge under the common weal to reap the bountiful rewards of a successful growing season. This was a grim task. While some of these Kansans feared the worst, none was prepared for what they were about to discover.

With hand to forehead, Ed York shaded his eyes, scanning the Benders’ orchard. “Boys!” he yelled as his gaze settled on a rectangular depression in the earth among the immature fruit trees. “I see graves!” The other men quickly converged on the hollow. Some began to dig feverishly, their shovels and spades clanging against one another. Before long their tools made contact with something hard—not a rock or a root, but something that didn’t belong there. They continued digging, more carefully now, until a body lay exposed. The men could clearly see that someone had bashed in the skull. One of the diggers rotated the corpse’s mutilated head slightly to the side, exposing a deep gash across the neck. There were gasps; the killer had knocked the poor fellow unconscious and then cut his throat. A sinking feeling hit York, but neither he nor anyone else could make an immediate identification—dirt and dried blood obscured the face, and the body was too decomposed to be moved. The men severed the head in order to wash the face clean. That done and the dead man’s hair parted, York had his worst fears realized. He was looking into the lifeless face of Dr. William York, his brother.

The doctor’s disappearance two weeks earlier was what had drawn his brother and friends to the Bender property that crisp morning. What had brought Dr. York there was an even earlier disappearance—that of a man named George Loncher and his daughter in the winter of 1872. It seems the doctor had sold the Lonchers a wagon and team that soon turned up deserted, with no sign of or word from father or daughter. Dr. York had left his home on Fawn Creek and traveled north of Fort Scott to identify the team. That task completed, he had mounted his horse and ridden for home. When the doctor didn’t show up, his brothers, Ed York and Kansas Sen. Alexander York, went out to find him. Using Fort Smith as a starting point, Ed and Alexander traced William’s movements along the Osage Mission Road. A number of people living along the road told the pair they had seen the doctor. One man even recalled that Dr. York had mentioned his intention to go to the Benders’ inn, nearly 80 miles southwest of Fort Scott.

The ghastly discovery of Dr. York’s body was just the tip of the iceberg. The cold-blooded Benders, with the brutal efficiency of predatory animals, claimed many victims in the early 1870s in Osage Township, Labette County, Kan. The diggers would harvest the bodies of other unwary travelers who had fallen prey. The family would become known as the Bloody Benders, and with good reason. Psychotic killers like John Wesley Hardin and Jim Miller roamed the post–Civil War West, but few of these warped individuals could hold a candle to the greed and dirty deeds of the family of serial killers that operated from their Kansas homestead.

Once authorities had relocated the Osage Indians to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) after the Civil War, homesteaders descended on Kansas’ Labette County. In 1870 the Benders were among the families that took advantage of the vacated area, building a cabin on their 160-acre claim along the Osage Mission Road (aka the Osage Trail or Trace) between Independence and Fort Scott. John Bender Sr., known as “Pa,” was about 60 and by all accounts sullen and ill-natured. Ma Bender, the heavyset woman said to be his wife, looked all of her 50-plus years and was as unfriendly as Pa. John Bender Jr., about 25, was somewhat more neighborly, but something about him, perhaps his inappropriate laughter, suggested he was simpleminded. He had a claim just to the north of Pa Bender’s but never lived on it or built any structures on it. Kate Bender, two years younger than her brother, seemed cut from a different cloth. She was reportedly both beautiful and outgoing. She didn’t act much like a farm girl. For one thing she advertised her services as a healer and spiritualist. Still, the true nature of the relationship between the Benders has always been uncertain. For example, it remains unknown whether Ma and Pa Bender were actually husband and wife. Some accounts had John Jr. and Kate married, not brother and sister. Others have suggested John Jr. was Ma’s son from a previous marriage and that his actual surname was Gebhardt. Some even claim the Benders were wholly unrelated. If the latter is true, killing unsuspecting folks seems to have drawn the foursome closer.

The Benders might not have been the friendliest folks around, but they welcomed visitors with money in their pockets. The family lived in the back of their cabin. In the front, beginning in 1871, they operated a small inn and store. What exactly happened when Dr. York paid the Benders a visit is uncertain. He was last seen on March 9. Since he lived in the area, it was puzzling as to why he chose to visit the inn. Perhaps he was hungry. More likely he suspected something. The Lonchers weren’t the only travelers to have turned up missing in the prior few months. The Benders may have slain the doctor out of sheer greed, but a more likely scenario is that he had voiced his suspicions or otherwise tipped his hand, and the Benders had decided to eliminate him.

In late March or early April, while investigating Dr. York’s disappearance, his brothers showed up at the Bender homestead. Kate was extremely cooperative, offering to contact the spirit world to help solve the riddle of the doctor’s disappearance. John Jr., however, concocted a farfetched tale of being waylaid and went so far as to take the York brothers to the supposed site of the attack. He further sought to throw the brothers off the scent, hinting at highwaymen in the area who possibly accounted for the doctor’s disappearance. Ed York, finding little credence in John’s tale, continued his search.

At the same time the residents of Harmony Grove assembled in the weathered clapboard school building for the annual school board election, held each year on the second Tuesday in April. On that day, April 8, 1873, residents hurried the election; there was a more pressing agenda—missing people. A determined clamor, each voice rising over another, called for action; in a disordered uproar, those gathered pledged punishment for those responsible for the missing residents. Pa Bender and young John were present at that meeting. One voice called out above the others, “What we need to do is search every foot of each of our farms!” A cold sweat must have gripped the two Bender men.

A couple of weeks after the meeting, Bender neighbor Billy Tole was driving his cattle past their meager farm and saw no sign of the family. Stopping to investigate, he found their livestock unattended—no feed, no water. A number of animals were tethered and unable to fend for themselves. One poor calf, its body held fast to a post in the stable, unable to free itself, had died of thirst, its mother nearby with her udders burst. Checking the house, Tole found it unoccupied. Where were the Benders?

The story of Tole’s findings spread throughout the region. People were up in arms over the mistreatment of the animals. Osage Township trustee LeRoy Dick sensed something more sinister, and on the morning of May 5 he went to investigate. After breaking the padlock on the door of the Benders’ cabin, he entered the cellar and met with a terrible odor—the stench of death. Looking up, he discovered a crude trapdoor with leather strap hinges, leading to the kitchen. Taking a quick inventory, he found three hammers; an eight-day clock, which upon further examination held a knife; pieces of jewelry; a German Bible; and some of Kate Bender’s occult advertising broadsides scattered across the kitchen floor. Dick called for a meeting of residents at the Benders’ the next morning, May 6, and men duly came armed with plows, teams and shovels. The spring harvest was on.

Drawn by the putrid smell and congealed blood on the cellar floor, Dick and about 50 other men from the township began their grim search there. But they found no bodies beneath the stone basement slab. By afternoon the crowd of diggers and morbidly curious onlookers had swelled to several hundred. Inside the house Ed York found a pair of spectacles and recognized a solder repair to the silver frame. They were his missing brother’s glasses. The search continued outside.

The men exhumed Dr. York’s body from the apple orchard and continued the harvest of bodies the next morning. Neither Pa nor Ma nor John Jr. nor Kate was among the planted dead on the property, so all doubt vanished that the Benders themselves might be victims. Quite the contrary, the true extent of the Benders’ ruthlessness became apparent. The diggers turned up the remains of at least nine other people in the orchard, including the pair for whom the doctor had gone searching—George Loncher and his daughter. Loncher’s skull had been crushed, but it was the state in which they found the girl, said to be about 8, that left the crowd of hardscrabble pioneers horrified. Her skull was intact, but she had a broken arm, among other injuries, and a scarf tied tightly around her neck, suggesting she may have been buried alive.

One of the victims was Henry McKenzie, cousin to LeRoy Dick’s wife; he had stopped to visit the Benders on November 6, 1872 (or perhaps the next day), on his way to see his sister in Independence. The killer had crushed the back of his skull (it was thought with a hammer swung from behind a curtain while he sat at a table awaiting supper), slit his throat (likely to ensure he was dead) and stabbed his lifeless body several times (perhaps out of frustration, as the traveler wasn’t carrying as much money as expected). The diggers found the bodies of Ben Brown, W.F. McCrotty and John Greary nearby; several other remains went unidentified. They found Johnny Boyle sitting upright in an old shallow well and at least four other suspected male victims off the Bender property. Exactly how many people the Bloody Benders killed between 1871 and 1873 remains unknown, but some estimates range over 20. How much money they made by emptying the pockets of their victims is also uncertain, though a quick tally set the amount at about $5,000. McCrotty reportedly carried $2,600 and Greary $2,000, but at least three of the victims had little more than pocket change. The question remains whether it was more than just greed that inspired the Bender bloodlust.

The grisly finds shook those who lived in and around Harmony Grove and Cherryvale. But the killings also stoked a thirst for vengeance. Someone had to pay for those vile murders. The Benders had fled to parts unknown, so residents singled out Rudolph Brockman, who had courted Kate Bender, for vilification. Surely, he must have known what was going on and had forewarned the Benders. A mob threw a noose around Brockman’s neck and jerked him upward while peppering him with questions; as he slipped closer to unconsciousness, the mob eased the rope. They repeated the painful procedure several times without any luck. Mobs rounded up other individuals, and in some cases entire families, and accused them of complicity with the Benders. They even took A.M. King, the preacher from Parsons, Kan., into custody for a while. The finger pointing and rush to judgment in southeastern Kansas had created an air similar to that surrounding the Salem witch trials nearly two centuries earlier.

The hunt for the Benders took on a life of its own. Ed York offered a $1,000 reward for information that would lead to the arrest of the Benders. Kansas Gov. Thomas A. Osborn followed this up in mid-May 1873 with a $2,000 reward for the apprehension of the foursome. Search parties—some legally sanctioned, some not—had little luck. The Bender buckboard was about all that turned up. A sign that had once hung over the inn’s front door—John Jr. had scrawled GROCRY on one side, and Kate had printed GROCERIES on the reverse—had been incorporated as a repair into the bed of the Benders’ wagon.

Other people sought not the Benders but macabre souvenirs from the old homestead. These relic hunters dismantled and carried off the entire inn and stable. “Thousands of people daily visit the grounds,” the Thayer, Kan., Head Light reported a week after the discovery of the bodies. “Last Sunday it was estimated there were 3,000 people on the grounds at one time.” Fortunately, LeRoy Dick had preserved some of the evidence, including three hammers thought to be the Benders’ murder weapons. On June 25, 1873, the Head Light ran a follow-up report, noting, “The whole of the house, excepting the heavy framing timbers on the Bender farm and even the few trees, have been carried away by the relic hunters.” The newspaper also addressed the flight of the outlaw family, suggesting, “The murderers themselves are probably in the middle of China by this time and will never be heard from.” Reporters and photographers from as far off as New York and Chicago converged on the killing ground.

Following up on the discovery of the Benders’ buckboard, Marshal Jim Snoddy from Fort Scott and posse members Colonel C.J. Peckham and Henry Beers went to Thayer, 12 miles north of the Bender inn, to inquire into train departures. Four people fitting the Benders’ description had boarded a train there for Humboldt, Kan. The Humboldt station manager said that from there John Jr. and Kate had taken a train south, while Ma and Pa Bender, carrying a doghide trunk (perhaps loaded with money), had taken another train to St. Louis. Snoddy, Peckham and Beers traveled there and learned that the two elder Benders had taken a carriage from the train station to the house of Pa’s sister but were long gone. The three lawmen returned to Kansas and, while checking the Southeastern rail lines, came across a baggage master on the Frisco line that had checked through to Vinita, Indian Territory, an unusual doghide trunk. Following that lead, the three-man posse boarded a train to Vinita.

Meanwhile, Albert Owens, the owner of a boardinghouse in Denison, Texas, reported that a tall young German railroad worker and his wife had pitched a tent near his establishment. An older couple visited them from time to time. The tall young one had reportedly suggested all four of them join an outlaw hideout along the Texas–New Mexico border. LeRoy Dick intercepted Peckham and Beers (Marshal Snoddy could not afford any more time away from his duties and had already returned to Fort Scott) in Vinita with this new intelligence. Changing direction, the two Kansans traveled to Texas and picked up the Benders’ trail, first 200 miles west of Denison and then again in El Paso and into the Chihuahua Desert, before giving up the chase. Some accounts say the Benders did reach the outlaw hideout, but there is no real proof.

On July 29, 1908, the Independence Tribune reported that conductor James B. Ransom said the Benders had boarded a train bound for Kansas City, from which they could connect to the East. “While the posses were racing about the country, the Benders were on the way to Europe,” Ransom suggested.

Over the years various newspapers reported sightings of Bender family members. A dispatch from Florence, Ariz., picked up by The New York Times on February 13, 1875, related the supposed capture of a man reported to be Bender after being tracked through west Texas. On July 7, 1873, the San Antonio Daily Express reported the two Bender women were under arrest in Winterset, Iowa. Nothing ever came of that or several other supposed sightings. But a story in the October 31, 1889, Chicago Daily Tribune claimed that two women arrested for larceny in Niles, Mich., had been identified as Ma and Kate Bender. The evidence was credible enough that LeRoy Dick traveled to Niles, with warrants in hand, and transported the prisoners back to Kansas. Authorities held the women for a few months, but a judge decided that the county had already incurred undue expenses and that the evidence against the women was insufficient, and he released them. Although authorities never proved the two were Ma and Kate Bender, Dick said he felt sure he had located the right women.

Although much time has passed, the Benders have not been forgotten. A Bender museum opened in Cherryvale in May 1961, during Kansas’ statehood centennial celebration, and operated there until 1978. Present-day Cherryvale Museum, which has limited visiting hours from April to October, displays the murder hammers and other memorabilia of the Bloody Benders. “Going on a bender” makes most people think of a drinking spree, but that expression will always have a slightly different meaning in southeastern Kansas, onetime home of the deadly sober Bender family.

David McCormick writes from Springfield, Mass. Suggested for further reading: The Benders in Kansas, by John Towner James; The Benders: Keepers of the Devil’s Inn, by Fern Morrow Wood; and The Saga of the Bloody Benders, by Rick Geary.