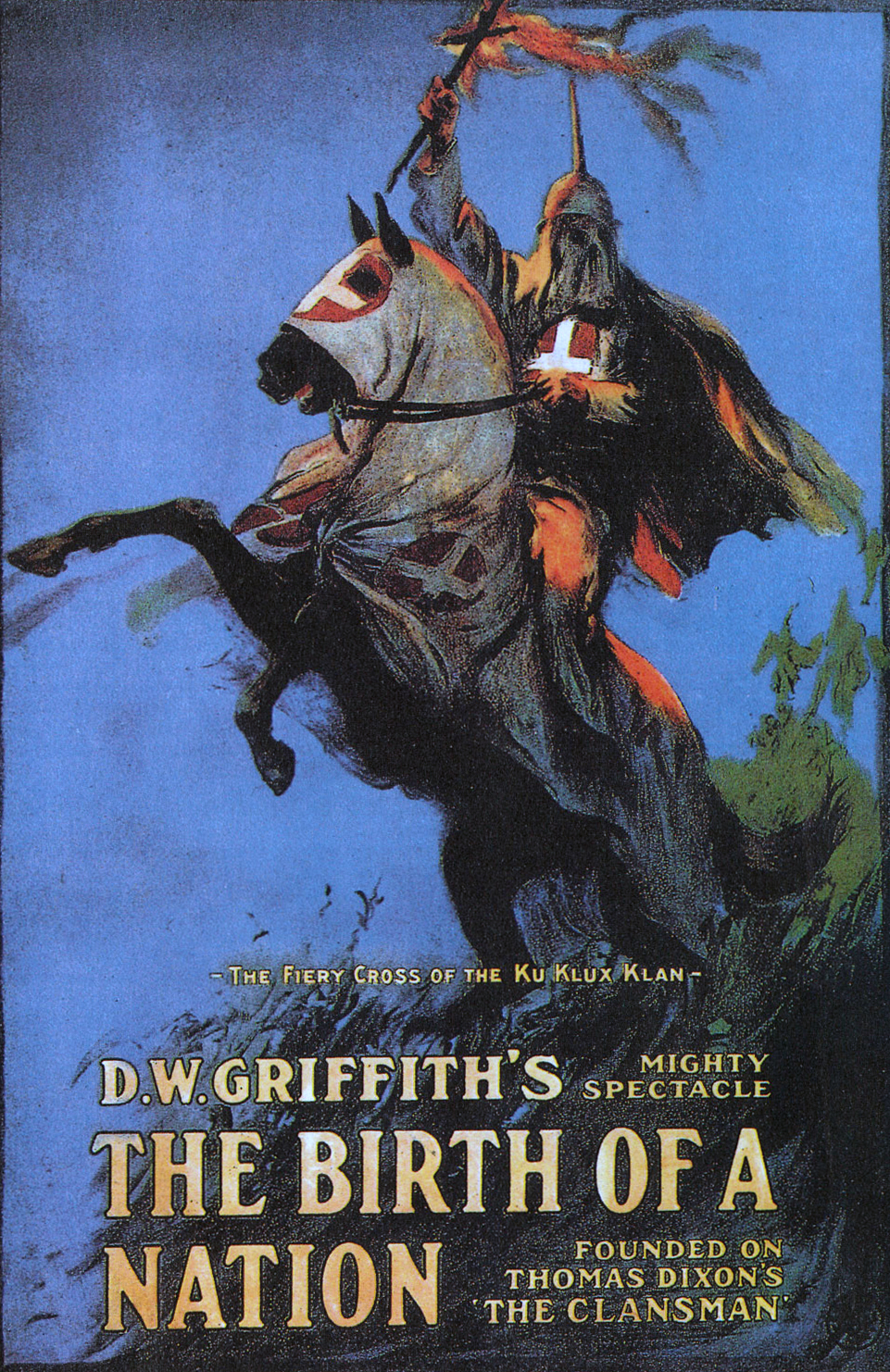

On July 4, 1914, director D.W. Griffith began work on a new movie called The Clansman, an epic about the Civil War and the subsequent agonies of Reconstruction. It was a major production, an epic in every sense of the word, with sets that seemingly filled every foot of his Fine Arts Studio in Hollywood, California.

Griffith was a curious figure who didn’t conform to the popular image of a silent-film director. Unlike his contemporary Cecil B. DeMille, he eschewed the usual costume of rolled-up sleeves, jodhpurs and riding boots, opting instead for a crisply tailored business suit complete with celluloid collar and immaculate tie. It was an outfit more in keeping with the boardroom than the cutting room, but it somehow reflected Griffith’s reserved Victorian persona.

The Clansman, later retitled The Birth of a Nation, is still considered a landmark of the American cinema. The film has been praised for its technical virtuosity and damned for its demeaning and racist depiction of black Americans. Birth was a kind of rite of passage for American movies, marking a transition from crude infancy to a robust adolescence. Griffith and his cameraman Billy Bitzer used a dazzling array of techniques to propel the story forward. Moving, tracking and panning shots gave new life to even static scenes. Crosscutting between two scenes built suspense, and the use of ‘cameo profiles and close-ups gave the movie a new emotional intimacy.

Although Griffith did not invent these techniques, he used them in such brilliant and innovative ways that it seemed as if he had. The director was a master storyteller, and by 1914 he was at the height of his powers. Monumental in conception, epic in scope and narrative power, the movie influenced filmmakers for generations to come. The Birth of a Nation was pure Griffith, and every frame of celluloid bore his stamp.

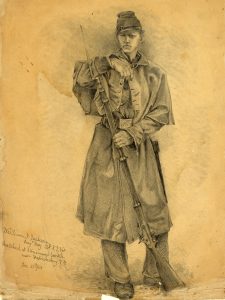

David Wark Griffith, son of Jacob Wark Griffith, was born on January 22, 1875, in Floydsfork, later Crestwood, Ky. The older man, nicknamed Roaring Jake, was a veteran Confederate colonel who had once commanded the 1st Kentucky Cavalry during the Civil War. Roaring Jake filled young David’s head with nostalgic tales of dashing, gray-clad cavaliers defending the antebellum way of life.

The Confederacy was no more, and slavery had been abolished, but by 1880 most of the civil rights that blacks had enjoyed immediately after the war had been taken away by newly reestablished white supremacist state governments. The Peculiar Institution, chattel slavery, had been replaced by a kind of serfdom in which black sharecroppers, debt-ridden and disenfranchised, were relegated to second-class citizenship.

Jacob Griffith died suddenly when David was only 10. The old colonel had been badly wounded in the war, and there was speculation that the injuries had been responsible—at least in part—for his demise. In any case, Roaring Jake’s passing caused quite a commotion, and his deathbed scene was forever etched in young David’s memory.

In later years, the director took great pains to hide his true self from the public, adopting a patrician reserve that exuded an air of mystery. But when he described his father’s death, he also unintentionally revealed his own deeply cherished core beliefs. When Griffith entered his father’s bedroom, he later recalled, he was met by a scene of grief and lamentation: Four old n——s were standing in the back at the foot of the bed weeping freely. I am quite sure they really loved him.

The unconscious racism and implied unquestioning acceptance of black inferiority in that statement reflect Griffith’s view of black-white relations. Thirty years later, those attitudes would find new expression in The Birth of a Nation.

As a young man, Griffith tried a variety of jobs but nursed a secret ambition to become a great playwright. Initially, he became an actor, traveling across the country and appearing in stage productions of varying quality. Finally one of his plays was produced in 1907. Titled A Fool and a Girl, it was an embarrassing flop.

Faced with near destitution, Griffith turned to motion pictures as a source of income. The movies in the 1890s were cheap entertainment for the masses. Working-class people, many of them European immigrants crowded into urban slums, flocked to nickelodeons for a few minutes’ escape from their daily toil. The early offerings were only about one reel long—that is, about 12 to 14 minutes. By 1910 more middle-class people were attending movies, but many still held a deeply rooted prejudice against them as cheap shows for cheap people.

Griffith shared these sentiments, at least at first, but then he began to see film in an entirely different light. He was among the first to grasp the potential of the movies—their as yet untapped power to educate as well as entertain. The fledgling movie actor soon joined the Biograph Company in New York City, where in addition to appearing in front of the camera he wrote film scenarios. When Biograph’s leading director became ill, Griffith was hired as a replacement.

The Adventures of Dollie, released in the summer of 1908, was Griffith’s first directorial effort. Within a few years, the helmsman had his own stock company, which included performers such as Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford, Blanche Sweet, Henry B. Walthall and Lionel Barrymore. Eventually, however, Griffith broke from Biograph and formed a partnership with Harry and Roy Aitken of Mutual. The Aitkens would stay in their New York base, while Griffith would set up shop in Hollywood. He had done some filming on the West Coast before, but now the move would be more or less permanent. Many Biograph people followed Griffith, including Lillian Gish and cameraman Billy Bitzer, so there was no shortage of talent on hand.

All the pieces were falling into place; now what was needed was a subject worthy of Griffith’s ambitions. A writer named Frank Woods introduced Griffith to a 1905 work titled The Clansman. It had achieved modest success as both a novel and stage play, and Woods was sure it would suit the screen. Griffith fully agreed and responded with alacrity. For him The Clansman was both inspired and inspiring, and it dealt with a subject close to his Southern roots.

The timing seemed right as well. The Civil War was very much in vogue, since the years 1911-15 marked the 50th anniversary of the bloody four-year conflict that had torn the nation asunder. More than 600,000 Americans had died in that self-inflicted holocaust, and millions had served in Northern and Southern armies. Many veterans were still alive and in 1913 there had been a great reunion of some 50,000 of them, Union and Confederate, at Gettysburg.

The Clansman, Griffith thought, presented an accurate account of the Southern side of the story. The director was interested in the social, not political, effects of the Civil War and its immediate aftermath. In the film, Griffith makes clear that he is not in sympathy with states’ rights and secession. After Lee surrenders to Grant, a title card speaks with seeming approval of Liberty and Union, one and inseparable, now and forever.

But Griffith the Southerner could recall the bitterness of Reconstruction through the tales told by his father and others. According to them, it was a time when Northern carpetbaggers descended on the prostrate South like a horde of ravenous wolves. Worse yet, they destroyed the natural order of society by giving blacks the franchise and equality with whites. The result, so this view held, was a period of suffering and white subjugation, until the depredations were reversed by the glorious exploits of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Clansman was written by Thomas Dixon, a lawyer-turned-Baptist preacher from North Carolina who was incensed when he saw a revival of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1901. To Dixon, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was Northern propaganda that depicted blacks in a favorable light and was full of lies and calumnies about the antebellum South and, by implication, the turn-of-the-century South as well.

Dixon set out to answer these lies with his own version of the truth in his 1902 novel The Leopard’s Spots: A Romance of the White Man’s Burden, 1865-1900. The book was a success, encouraging Dixon to pen The Clansman in 1905. That same year, a stage version of The Clansman appeared that was an amalgam of both works. The stage production enjoyed a successful road run, though box office receipts were perhaps greater in the South, where it struck a responsive chord with white audiences. Dixon initially wanted $25,000 from the filmmakers for the movie rights, but then agreed to $2,000 up front and 25 percent of the gross.

In his works, Dixon expressed some then common views on Reconstruction. The preacher once noted, my object is to teach the North, the young North, what it has never known—the awful suffering of the white man during the dreadful Reconstruction period. He went on to say that he believed Almighty God anointed the white men of the South by their suffering…to demonstrate to the world that the white man must and shall be supreme. These were sentiments that D.W. Griffith endorsed as well.

The shooting schedule was a long one, lasting from July to November 1914. The first part of the film is highlighted by spectacular battle scenes, some of the best ever committed to celluloid. They were shot in the San Fernando Valley, between today’s Warner Brothers Studio and Universal City.

The movie’s plot revolves around two families, one Northern and one Southern. The Stoneman clan is headed by Congressman Austin Stoneman, a Northern abolitionist and Radical Republican who is loosely based on real-life Pennsylvania Senator Thaddeus Stevens. Stoneman has three children, sons Phil and Tod, and a vivacious daughter named Elsie, played by Lillian Gish.

When the film opens, Phil and Tod are seen visiting their old boarding school friends the Camerons, Southern gentry who live in Piedmont, S.C. In the epic, life in the prewar South is depicted in an idyllic moonlight and magnolias fashion, with paternalistic whites taking care of happy, carefree slaves.

Ben Cameron, nicknamed The Little Colonel, develops a romantic attachment to Northern Elsie, and she welcomes his attentions. In similar fashion, eldest Northern son Phil Stoneman falls in love with Southern belle Margaret Cameron. But these promising romances are cut short by the outbreak of the Civil War. Griffith is at his best in depicting both the horrors and heroism that war engenders. In the scenes portraying the Battle of Petersburg, Ben leads a heroic, if ultimately futile, assault against the Union lines. He is badly wounded and captured.

The war ends with the North triumphant, but then President Abraham Lincoln is assassinated. His death signals the start of Radical Reconstruction, and Congressman Stoneman is now a power in the land. He dispatches his henchman, the mulatto Silas Lynch, to Piedmont to establish carpetbagger rule and black supremacy. As the story continues, Southern whites are degraded, abused and forced to acknowledge blacks as equals. Lawless blacks freely engage in pillage and rapine, while whiskey-swilling black politicians lustfully leer at white women and crudely scratch bare feet.

His soul tormented by the ruin he sees all around him, Ben Cameron is close to utter despair when he sees some white children don sheets and pretend to be ghosts. Their childish masquerade scares some black youngsters, providing Ben with the inspiration he needs to create the Ku Klux Klan.

The film builds to a powerful climax. When a former slave named Gus makes advances to another Cameron daughter, Flora, she loses her balance and falls off a cliff. The title card opines that Flora found sweeter the opal gate of death—that is, death was preferable to a possible rape or even a black man’s embrace. Ben witnesses his sister’s fall or leap (the action is ambiguous) and swears revenge.

The Klan then appears on screen, decked out in full white-sheeted regalia, as avenging knights who track Gus down and give him a fair trial before lynching him. His lifeless corpse is dumped at Silas Lynch’s door as a warning. The mulatto leader reacts, throwing off all restraints in a bid for ultimate power. His black militia ravish the land, and at one point trap some of the Cameron family and Northerner Phil Stoneman in a cabin that just happens to be the abode of two Union veterans. The Yankees welcome the fugitives, and before long the former enemies of North and South are united again in common defence of their Aryan birthright.

Meanwhile, Silas Lynch tells Elsie he wants to marry her. Even the staunch abolitionist Congressman Stoneman recoils in horror at the thought of this race-mixing, this miscegenation, and the possibility of a black son-in-law. Lynch, however, is undeterred, and proceeds with plans for a forced wedding.

In a series of exciting crosscuts and tracking shots, the Klan rides to the rescue in the nick of time. The Camerons are rescued from the black militia, and Silas Lynch’s nefarious plans are foiled. The forces of black Reconstruction are defeated by the triumphant Klan. At film’s end, Ben and Elsie are reunited, and peace, justice and white supremacy are restored to the South.

After some sneak previews on January 1 and 2, 1915, the movie was scheduled to have its official premiere on February 8 in Los Angeles. The local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) tried to get an injunction to stop the premiere, but the legal argument had too narrow a focus and failed to stop the screening. The NAACP, founded in 1909, was composed of both blacks and white liberals and actively campaigned for black rights.

The Los Angeles premiere was a triumph, but the picture’s real test would be its New York opening in March. In 1915 Los Angeles was still considered a cultural backwater, but New York City was thought to be the cultural capital of the nation. No expense was spared for the film’s Gotham debut. The Liberty Theatre, near Times Square, was leased for the premiere and its subsequent run. It was also announced that the top admission price would be $2, a steep tariff in an era when a first-run picture ticket might cost 25 cents.

Everyone associated with the picture—now retitled The Birth of a Nation—knew they had won a censorship skirmish with the NAACP, but the civil rights organization was far from conceding defeat. In fact, the Los Angeles clash was only the first round. Thomas Dixon was impressed with the movie, and decided to pull some strings to ensure its ultimate success.

Dixon remembered an old college friend from his student days at Johns Hopkins University. The friend’s name was Woodrow Wilson, and he just happened to be president of the United States. The Clansman author quickly penned a letter to the White House asking for a half-hour meeting with the president. It was granted, and Dixon did all he could to flatter Wilson—not as the nation’s powerful chief executive but as a scholar and student of history and sociology.

The wily Dixon knew his schoolmate well. Wilson was an academic at heart and was willing to view this controversial motion picture. But there was a problem—Wilson was still in mourning for his first wife, and publicly attending a movie theater would be out of the question. The president suggested a solution to the dilemma: Why not have a special screening at the White House? This was more than even Dixon had expected, and arrangements were soon made.

The Birth of a Nation was shown to the president, the cabinet and staff members on February 18, 1915. It was the first time a film was ever officially screened at the White House. Wilson was a Southerner, a man who endorsed Jim Crow segregation in Washington, D.C., so the film’s basic premise was one the president seemed to share, at least in part. The fact that many of the movie’s title cards were excerpts from Wilson’s own 1902 work, History of the American People, certainly didn’t hurt.

Wilson was awed by the movie, commenting that it was like writing history with lightning, adding, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true. The president’s ringing endorsement gave the picture a new credibility. Dixon’s shrewd maneuver had paid off.

The NAACP tried to stop the upcoming New York premiere by appealing to the National Board of Censorship. The movie was shown to the entire board, some 125 people, and a few of the more liberal members—notably Chairman Frederic C. Howe—found the blatant racism disquieting. But the board as a whole was dazzled by the movie’s sheer narrative power and sweeping spectacle. It was decided the film could be shown, though the board would withhold formal approval until a few strategic edits were made.

In an 11th-hour attempt to stop the premiere, the NAACP argued in court that the picture endangered the public peace. In other words, the inflammatory nature of the subject matter would cause racial tension, possibly even riots. The judge was unmoved; the premiere would go on as planned.

The March 3, 1915, opening was a personal and professional triumph for Griffith. Thousands of New Yorkers flocked to see the movie, in spite of the $2-a-seat ticket price and a running time of almost three hours. The NAACP picketed the Liberty Theatre, but they were virtually ignored by eager patrons waiting to be admitted. The Birth of a Nation played in New York for 10 months, during which an estimated 825,000 viewed the film.

Ten days after the premiere, social reformer and NAACP member Jane Addams blasted the film in an interview published by the New York Post. Addams, best known for her work among the urban poor and immigrant populations of Chicago, was a respected figure whose opinion mattered. She hated the racism she saw in the film, especially the pernicious caricature of the Negro race.

Unfortunately, the protests of Addams and others were drowned out by the swelling chorus of critical, and even academic, approval. A new Epoch of art is reached, enthused the New York Herald, while the New York Globe was of the opinion that never before has such a combination of spectacle and tense drama been seen.

Griffith was genuinely hurt by the controversy. He loved Negroes, he claimed, and felt white Southerners had a special rapport with blacks and a unique understanding of their natures. To accuse him of prejudice against blacks is like saying I am against children, as they were our children, whom we loved and cared for all our lives. The idea that blacks might have wanted a higher degree of human dignity and to be treated as adults, not children, seems never to have crossed his mind.

The major black roles in The Birth of a Nation are played by white actors. Their faces are covered with burnt cork, and there is some suggestion of whitened lips that harkens back to the popular minstrel shows of the 19th century. Griffith tried to sidestep the issue by claiming he had given the matter careful consideration, but there was not going to be any black blood among the principals. The implication was that blacks lacked both the intelligence and talent to play a character of their own race.

It is true that Dixon’s ranting, hysterical, almost foaming at the mouth racism is toned down in the movie. In his book, a black is a thick-lipped, flat nosed, spindle-shanked Negro, exuding his nauseous animal odor. Griffith’s dreamy-eyed Victorian romanticism eliminated the viciousness, substituting a paternalism that was ultimately just as offensive. Griffith’s South is a mythic one, rooted in his own nostalgic childhood memories and in the pro-Southern scholarship prevalent at the time.

Griffith was a man of his time and place, sincere in his misguided beliefs. He may not have anticipated the storm of controversy that was about to break over his head, but he was smart enough to hedge his bets. In an obvious effort to disarm his critics, Griffith added a title card that firmly states, This is an historical presentation of the Civil War and Reconstruction period, and is not meant to reflect on any race or people of today.

In Griffith’s world there are two kinds of blacks. The first are described in the subtitles as Faithful Souls, childlike Uncle Toms, who know their place and accept their natural inferiority. Happy and contented, eager to do ole massa’s bidding, they can work 10 hours in the cotton fields and still dance and sing for de white folks at the end of the day. They know that racial equality will only lead to disaster. Yo’ northern low-down black trash! a faithful Cameron maid declares when she sees a Northern black. Don’t try no airs on me!

The other kind of black is the renegade, who refuses to accept his lot and dares to think he is as good as a white person. Denied the guidance of his betters, he soon falls into a life of laziness, vice and crime. Griffith insisted that, appearances to the contrary, carpetbagging Northerners, not renegade blacks like Silas Lynch, were the real villains of the story. In his view, scheming Northern politicians and carpetbaggers used the blacks as dupes to further their own ends. While white Southerners were distracted by black depredations, white Northerners moved in to secure both wealth and power behind the scenes.

Its efforts to ban the film having proved abortive, the NAACP decided to change tactics. It would try to get the most offensive scenes cut from existing release prints—a partial concession to the film’s enormous popularity with white audiences as it opened across the country. Black leader W.E.B. Dubois entered the fray, writing a series of scathing attacks against Birth’s unvarnished racism, and the NAACP published a 47-page pamphlet entitled Fighting a Vicious Film: Protest Against The Birth of a Nation.

Matters came to a head in Boston, where Mayor James Curley convened a special meeting to determine if all showings of The Birth of a Nation should be banned. Curley was concerned about the possibility of violence: There had been threats to blow up the theater with dynamite. But, the mayor said, the gross black caricatures in the film were no different than the exaggerations one would see in productions of Shakespeare.

Defenders of the film came forward, but were drowned out by a chorus of hisses, boos and catcalls from civil rights advocates. D.W. Griffith himself was saluted with a loud and raucous round of boos when he tried to argue against censorship. Moorfield Storey, the white head of Boston’s NAACP, challenged Griffith’s claims of absolute historical accuracy. He asked the director if it was historic that a [henchman like Lynch] held a white woman in a room and demanded forced marriage!

Of course Storey was right. In spite of the film’s historic set pieces—like the Lincoln assassination and Lee’s surrender at Appomattox—many incidents were wholly fictitious. The Klan was not created by a man who watched some white children playing ghost. It was founded by a group of former Confederate officers in Tennessee, and in May 1866, famed cavalry general Nathan Bedford Forrest became their Grand Wizard. What began as a charitable organization that helped Confederate widows and orphans soon took a more sinister turn. Klansmen used intimidation, torture and even murder against carbetbaggers and scalawags and to prevent newly enfranchised blacks from going to the polls. As violence in the name of the KKK increased, the original group disbanded in 1869, but loosely formed klaverns continued to operate throughout much of the South. Following a government crackdown on such groups, notably through the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments, the Civil Rights Enforcement Act of 1870-71 and the Ku Klux Act of 1871, these groups, most of whose goals had been achieved anyway, withered.

Griffith knew that many of his plot details were fictional but tried to deflect this criticism by inviting his adversary to come see the play. The director tried to shake hands with Storey, who recoiled with an icy, No, Sir!

The stage was set for a confrontation. A few of the more offensive scenes were cut for Boston consumption, but many racist episodes still remained. Black activist and newspaper publisher William Monroe Trotter led some 200 African Americans to a place just outside the Tremont Theater, where The Birth of a Nation was playing to packed houses. The theater had hired Pinkerton detectives in anticipation of trouble, and they were soon joined by uniformed Boston police.

Trotter and a few followers entered the lobby, but when they tried to buy some tickets they were bluntly told, Sold out! It wasn’t true, and Trotter knew it, so he repeated his request for a ticket. Again he was refused, but this time he was told to leave the theater. When he loudly protested against this blatant discrimination, the police acted to forcibly remove him. A scuffle broke out, and in the melee Trotter was hit by a policeman’s billy club. Trotter and 10 other blacks were arrested and led away.

But other blacks and a few sympathetic whites had managed to sneak into the theater, where they caused an uproar by jeering during racist scenes and pelting the screen with eggs. Some of the protesters went a step further by detonating stink bombs that filled the auditorium with an acrid stench. After the movie ended, violence flared in the streets, with groups of blacks and whites battling it out until arrested by the police.

The New York and Boston screenings were only two of the battles in an increasingly acrimonious debate about the picture and its merits. When the NAACP appealed to local censorship boards or government officials, they met with varying responses. Usually the most blatantly racist scenes were cut, not because they were offensive, but because they might incite violence or race riot.

The movie was banned in a few places, including the entire state of Kansas (a restriction lifted in 1923). Picket lines and protests only sparked people’s interest and curiosity and added to box office receipts.

Blossoming from the burgeoning Nativist movement in the early 20th century, the KKK was reincarnated in 1915 by Atlanta businessman William J. Simmons. This version, which claimed some 5 million adherents by 1925, not only opposed black equality but was also anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic and anti-immigrant. Unfortunately, The Birth of a Nation became a recruiting tool for the revived Klan, which was certainly not Griffith’s intention. Some have claimed that Griffith’s epic sparked the resurgence of the Klan since Klan recruiting propaganda was sometimes printed side by side with the movie’s theater ads. The film’s impact on that resurgence, though considerable, has been grossly exaggerated.

In spite of all the controversies, vilifications and court battles, The Birth of a Nation was a critical and popular success, far and away the most profitable film of the silent era. After its initial run, it was rereleased in 1924, 1931 and 1938. If the rereleases are added to the totals, Birth earned somewhere between $13 and $18 million.

D.W. Griffith became a household name, lionized by press and public alike. Birth’s huge profits gave him a kind of creative independence, but he failed to change with the times. He continued making films—Intolerance in 1916, followed by, among others, Orphans of the Storm, Way Down East and Abraham Lincoln. He directed his last movie, The Struggle, in 1931, in the early sound era. His peculiar brand of Victorian romanticism, however, had fallen out of favor by the late 1920s. While many of his later films were successes in one way or another, D.W. Griffith died in 1948 without having produced another motion picture that generated the kind of critical acclaim, box-office success and controversy that The Birth of a Nation did.