It was Feb. 16, 1953, and famed Boston Red Sox left-fielder Ted Williams was sliding into home like he’d never slid before. For one, he wasn’t on a baseball field, and the action was definitely not part of any game.

A Marine Corps Reserve aviator and World War II veteran, Williams had been recalled to active duty just over a year earlier and was now using all his considerable flying skill to nurse his badly damaged F9F Panther toward an emergency landing. Shrapnel had knocked out the fighter’s hydraulics, meaning Williams could not lower the Panther’s landing gear or flaps. Burning fuel streamed from the jet’s punctured tanks, threatening to turn the aircraft into a ball of fire at any moment.

With the alternate field in view Williams made a straight-in approach, holding the crippled Panther just off the runway to bleed off airspeed. When he judged the jet was about to stall, he set it down as gingerly as possible. Yet as soon as the fighter’s belly touched the unforgiving concrete, a sheet of fire erupted from the damaged tanks.

Flames billowed out behind the plane as it slid down the runway, finally coming to a grinding halt some 2,000 feet from its touchdown point. Ejecting the canopy from the cockpit, Williams tumbled to the ground and ran to safety. It was by far the most dramatic home run the ballplayer turned combat aviator ever made.

The man who would become one of America’s most celebrated athletes was born Theodore Samuel Williams in San Diego on Aug. 30, 1918. He was named after former president Theodore Roosevelt and his own father, Samuel Stuart Williams, a soldier, sheriff and photographer from New York who admired Roosevelt. Like his famous namesake, Williams loathed the nickname “Teddy.” Just the same, fans fondly referred to him as “Teddy Ballgame.”

A left-handed batter, Williams got his start in professional baseball while still a high school senior, playing for the Pacific Coast League’s San Diego Padres. In 1936 the 18-year-old posted an impressive .271 batting average on 107 at bats in 42 games for the Padres. He also caught the eye of Boston Red Sox general manager Eddie Collins during a doubleheader that August.

In 1937, having graduated high school in the winter, the young slugger returned to the Padres. The team won the Pacific Coast League title that season, Williams knocking out 23 home runs and getting a hit nearly one of every three times at bat. Collins had kept in touch with his Padres counterpart, Frank Shellenback, regarding Williams’ future, and the two struck a deal that December. The agreement sent the future Hall of Famer to the Red Sox in exchange for two major leaguers and two minor leaguers. The kid was wanted.

Williams made his major league debut with the Red Sox in 1939. By season’s end he’d managed a hit one of every three times at bat, with 31 home runs and 145 runs batted in, making him the first rookie to lead the American League in RBIs. He also led the league in walks, another rookie record. (Pitchers justly feared throwing “The Thumper” hittable pitches, so they walked him instead.)

Though no Rookie of the Year award existed in 1939, baseball legend Babe Ruth proclaimed Williams the unofficial holder of the title. “That was good enough for me,” Williams recalled in his autobiography. Also noteworthy were Williams’ 1940 and ’41 seasons, the latter often considered the all-time best offensive season for a ballplayer—though the Most Valuable Player award that year went to fellow baseball icon Joe DiMaggio. Williams’ .406 average earned him the first of six batting championships and remains the highest single-season average in Red Sox history. He also led the major leagues with 135 runs scored and 37 home runs.

During the winter break between the 1941 and ’42 seasons the Japanese attacked the Pacific Fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, drawing the United States into World War II. The ’42 season kicked off as usual that spring, but the entire country had shifted into wartime readiness.

Williams had been classified 1-A, the most eligible draft category, and in January he received notice to report for duty. He instead informed his draft board that he was his mother’s sole financial support, as younger brother Danny had a troubled past and had even pawned appliances Ted had purchased for mother May. Were he killed in service, Williams argued, his divorced mother would be left destitute. The draft board agreed and changed his classification to 3-A, deferring his call-up.

When news of Williams’ successful appeal to the draft board leaked to newspapers, however, the public didn’t take it well. To deflect the negative press, he publicly stated his intention to enlist as soon as he’d built up his mother’s trust fund. Yet the media continued to ride him, leading to the withdrawal of an endorsement contract with Quaker Oats. The Red Sox front office and Williams ultimately agreed it would be better if he joined up sooner rather than later, and on May 22, 1942, the young ballplayer enlisted in the U.S. Navy Reserve.

As a headline-grabbing major leaguer, Williams could have safely spent the war playing ball on various U.S. Navy base teams. While that is exactly what the more cynical sportswriters and fans assumed he would do, Williams envisioned serving the country in a more meaningful capacity. An action-oriented athlete with tremendous reflexes and hand-eye coordination, he wanted to be an aviator—specifically, a naval aviator.

While individuals seeking to become fixed-wing fliers in the present-day U.S. service branches are required to hold a bachelor’s degree, that was not a hard-and-fast rule during World War II. Though Williams had only a high school diploma, the Navy was happy to accommodate him. After finishing the 1942 season, the young ballplayer entered the Navy’s preliminary ground school at Amherst College in Massachusetts for six months of academic instruction in such relevant subjects as mathematics and navigation. He excelled in almost every course, turning in better grades than many of his classmates with college degrees.

The students also received rudimentary flight training, and Williams took to it like a natural. Capping off a busy year, he won the 1942 Major League Baseball Triple Crown for having led the American League in batting average, home runs and RBIs.

After completing his academic courses at Amherst, Williams undertook basic flight training at Naval Air Station Bunker Hill, Ind., and advanced training at NAS Pensacola, Fla. It soon became apparent the superb coordination and reflexes that made him an outstanding baseball player would also serve him well as a pilot. He received his gold naval aviator wings and a commission as a Marine Corps second lieutenant on May 2, 1944. Williams then went to NAS Jacksonville, Fla., for a 10-week course in aerial gunnery, a combat pilot’s graduate-level test. There he broke all records in reflexes, coordination and visual-reaction time, his instructors noting that his mastery of those qualities made him almost an integral part of the aircraft.

Williams qualified to fly the Vought F4U Corsair. His command of the gull-winged fighter was such that NAS Pensacola retained him to teach other young Navy and Marine Corps pilots to fly the Corsair. After a year as an instructor Williams was sent to Pearl Harbor to await combat assignment to the western Pacific, but the war ended before he could deploy. He was released from active duty on Jan. 12, 1946.

Williams made it back to Boston for the start of the 1946 season, and the next several years were the most productive of his career. The Baseball Writers’ Association of America named him the American League’s Most Valuable Player in both 1946 and ’49. He earned his second Triple Crown in 1947—only the second major league ballplayer to have done so (Rogers Hornsby was the first, in 1922 and ’25). Williams was also named the Red Sox’s MVP in 1946 and ’49. During the 1949 season he also set a record by reaching base in 84 consecutive games.

Probably the farthest thought on Williams’ mind in those immediate postwar years was the possibility of renewed military service. After his 1946 discharge from active duty he’d retained his commission in the inactive component of the Marine Corps Reserve. As an inactive reservist he was exempt from attending either weekend drills or active-duty training in summer. His was but one name on a very long list. The odds seemed just as long his service affiliation would ever again interfere with his baseball career.

Then, on June 25, 1950, the Korean peninsula erupted in war.

In the aftermath of World War II all U.S. military branches underwent massive drawdowns. A vastly curtailed aviation budget prompted the Marine Corps to release large numbers of aviators to the inactive reserve, which meant the Corps was desperately short of pilots when war broke out in Korea. The obvious answer was to recall inactive aviators to service. To his surprise Ted Williams was among those summoned.

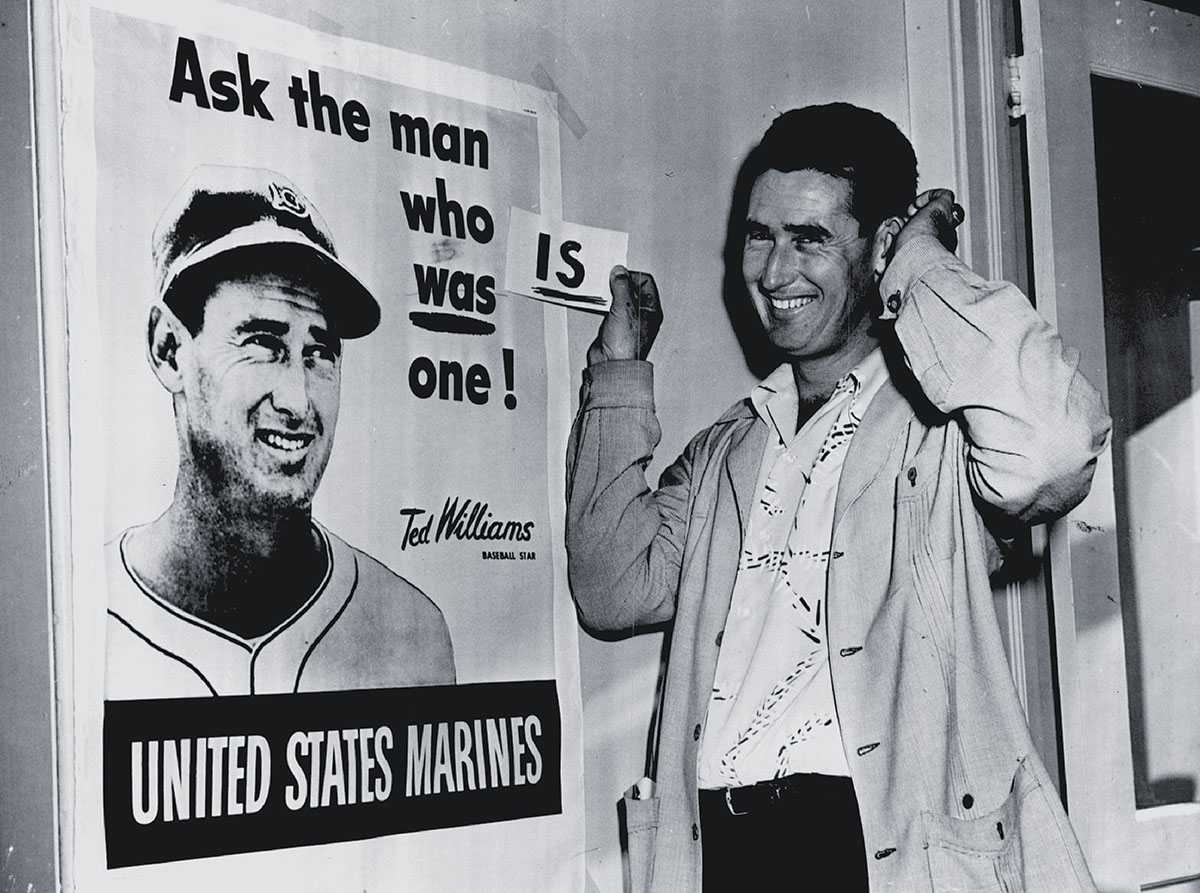

The pride of the Red Sox was preparing to enter spring training for the 1952 season when the call came on January 9, catching him completely off guard. Williams believed that at the conclusion of World War II he and Marine Corps Commandant Gen. Alexander Vandegrift had reached a mutual agreement—the ballplayer would let the Corps use his name for public relations and recruiting purposes in exchange for Williams never having to serve another day on active duty. That understanding was voided, however, by a simple error.

As Marine Corps administrators reviewed the names of inactive reservists who hadn’t been called up, they pulled the index card of one Theodore S. Williams in Boston. The clerk who read the name didn’t connect it with the popular ballplayer and set the wheels in motion for his activation. Once news of the recall broke, it would have smacked of favoritism to refuse. So, on May 2, having played in only six major league games, newly promoted Capt. Williams reported for active duty—first attending a refresher course at NAS Joint Reserve Base Willow Grove, Pa., followed by operational training at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, N.C.

After qualifying in the new Grumman F9F Panther, Williams was assigned to Marine Aircraft Group 33 (MAG-33), comprising two fighter squadrons based at K-3 in Pohang, South Korea. He joined squadron VMF-311 in early February 1953, around the same time as Maj. John Glenn, the future astronaut and U.S. senator. Williams even served for a time as Glenn’s wingman. The North Korean air force at the time was negligible, so most of the squadron’s sorties involved flying close air support missions for Marines and soldiers on the ground.

The Panther was ideally suited to such a task. One of the first successful jet-powered carrier aircraft, the single-engine, straight wing F9F-5 flown by VMF-311 was armed with four 20 mm cannons, while its eight underwing ordnance racks could accommodate up to 3,465 pounds of bombs and rockets. Even though MAG-33’s airfield was nearly 200 miles from the front lines, Panthers often led the attack in advance of propeller-driven F4U Corsairs. The Panther’s flight characteristics were superior not only in sheer speed, but also in offering a stable platform that enabled more accurate gunnery, bombing and rocket fire.

On February 16 Williams participated in his first combat mission, a major strike against a heavily defended tank and infantry training complex south of Pyongyang, North Korea. The Panthers’ main ordnance consisted of 250-pound bombs. On the attack run Williams’ F9F-5 was hit—whether by ground fire or shrapnel from his own bombs was never determined.

The damage was extensive, and Williams elected to divert to airfield K-13, in western South Korea, rather than attempt a return to K-3. He emerged unscathed from the spectacular belly landing, but his Panther was a write-off. Back in the air the next day, Williams completed 39 combat missions in Korea before the armistice was signed on July 27.

Once again a civilian and back stateside, Williams practiced with the Red Sox for 10 days before playing in his first postwar game, on Aug. 6, 1953. While his appearance on the field as a pinch hitter in the ninth garnered an enthusiastic ovation from the crowd, he popped out, and the Red Sox lost to the St. Louis Browns (the soon-to-be Baltimore Orioles), 8–7. He’d soon find his groove. In the 1953 season Williams went to bat 110 times in 37 games and ended up hitting .407 with 13 home runs and 34 RBIs.

In 1957 Williams led the major leagues in batting average, and in ’58, at age 40, he led the American League in batting average. Fittingly, Williams ended his playing career with a home run in his last at-bat on Sept. 28, 1960. He is one of only 29 players in baseball history to have appeared in major league games over four decades.

In retirement Williams started his own baseball camp, for boys aged 7 to 17, in Lakeville, Mass. He was also a regular visitor to the Red Sox’s spring training camps in Florida, where he worked as a batting instructor through 1966. That year, on his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., he was named a team vice president.

In 1969 Williams signed on as manager of the D.C.–based Washington Senators, and he remained with the team through 1972, a year after it had moved south to Arlington, Texas, as the renamed Rangers. Williams’ best season as a manager was 1969, when he led the expansion Senators to its only winning season and was chosen American League Manager of the Year. He resumed his role as spring training instructor for the Red Sox in 1978.

In his downtime Williams was an avid fly and deep-sea fisherman, who in 1999 was inducted into the International Game Fish Association Hall of Fame. He was also a committed supporter of the Boston-based Jimmy Fund for children’s cancer research and treatment, having lost brother Danny to leukemia at age 39 in 1960. In later life the famed former ballplayer developed heart disease. Following a series of strokes and congestive heart failure, Ted Williams—baseball legend and veteran of two wars—died on July 5, 2002, at age 83 in Inverness, Fla. MH

Retired U.S. Marine Col. John Miles writes and delivers lectures on a range of historical topics. For further reading he suggests Ted Williams: A Baseball Life, by Michael Seidel; My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life, by Ted Williams with John Underwood; and Ted Williams at War, by Bill Nowlin.

This article appeared in the March 2021 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: