IN MOST ACCOUNTS of the 1930s, he’s the patsy, the slightly daft gent carrying his signature umbrella, a weakling willing to do anything to appease Adolf Hitler and prevent the Third Reich from launching World War II. Less than a year before the outbreak of human history’s most horrific conflict, he stood on the tarmac at London’s Heathrow airport, waving a piece of paper and boasting to fellow Britons that the document he and Mr. Hitler had just signed meant nothing less than “peace in our time.” The Führer thought otherwise, and ever since, Neville Chamberlain has stood before the bar of history accused, indicted, and convicted of Terminal Stupidity and Toadying to Evil. Indeed, what else is there to say about someone who actually seemed to trust Adolf Hitler?

History is rarely so cut and dried, however, and there is another story to tell about Chamberlain. As a central figure in British politics during a tumultuous decade—first as Chancellor of the Exchequer 1931–1937, then as Prime Minister—Chamberlain had to address a complex of problems that reached well beyond a revived Germany and a ranting dictator. Britain faced threats across the globe: Germany in Europe, Italy in the Mediterranean, and, perhaps most troubling of all, Japan in Asia and the Pacific. A war with any one of those three surely would lead the other two to horn in on British territories or possessions. Notions that Chamberlain did not comprehend the threat Germany posed or that appeasement constituted moral cowardice on his part or that Winston Churchill was the only figure on Britain’s political scene calling for rearmament and a hard line against Hitler—all standard to the anti-Chamberlain dossier—oversimplify history to the point of falsity.

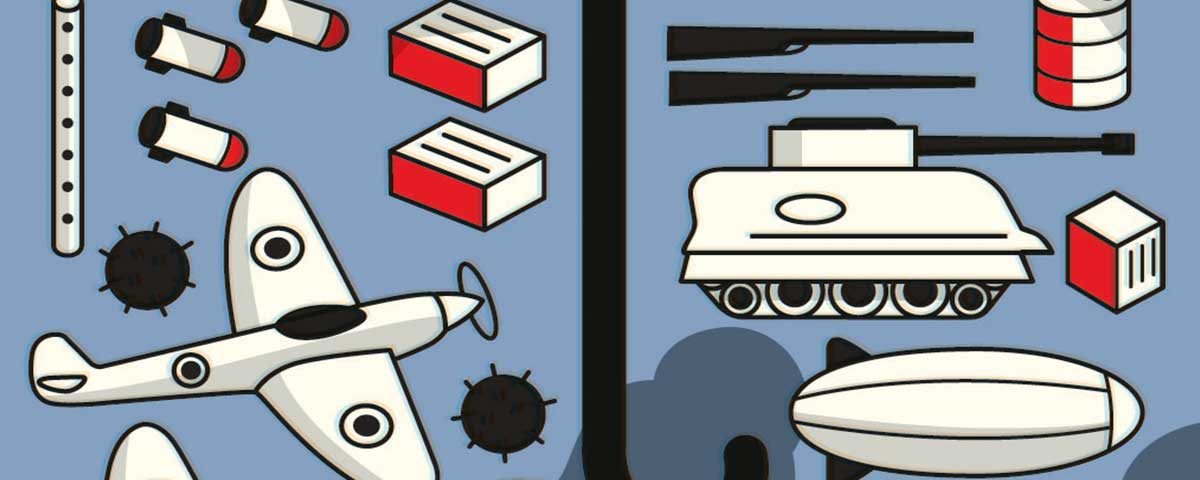

In the late 1930s just about every important figure in British government, or at least in the Conservative Party, knew it was time to spend on national defense. In November 1933, 10 months after Hitler seized power, the British cabinet created a committee on defense requirements to study the cost of military modernization and how long the process would take. That planning culminated in early 1935 in a “White Paper.” The findings? Even if rearmament began immediately, Britain would not be ready to fight Germany until 1939. The analysis described weapons not yet in production, some of them only prototypes or sketches. The “Thirty-Niners,” as rearmament advocates were called, realized wishes took time to become reality, and that until then the thing to do was negotiate, buy time, and avoid a new war.

And so, from 1935 on, Britain was in a juggling act: trying to appease Hitler, but also feverishly girding for an inevitable war. In that context, Chamberlain’s much-maligned policy, distasteful as it appears, made some sense. Engaging Hitler in talks and turning a cheek to his invective gained Britain time to man up. Chamberlain probably did feel his actions might make war unnecessary, and even if he failed he could say—as he did on September 1, 1939—that he acted “with a clear conscience.”

By then Britain was ready to fight—or at least far readier than a year before. “Last September we might have lost a short war,” Lieutenant General Henry Pownall, the army’s chief planner, wrote at the time. “Now we shouldn’t, nor a long one either.”

Even the inspirer-in-chief, speaking at the White House in 1954, tacitly endorsed Chamberlain’s prewar posture. “It is always better to jaw-jaw than to war-war,” Churchill said. But no one will ever completely rehabilitate Neville Chamberlain. In a dark hour, he failed to inspire the British, and always will suffer by comparison to his successor. Once hostilities began, Chamberlain had no more business leading the Empire than I would have, and his famous utterance that Hitler had “missed the bus,” hours before Germany invaded Scandinavia in April 1940, confirmed his hopelessness in the strategic and operational arena.

Even so, Chamberlain oversaw the British rearmament that delivered Hurricanes and Spitfires, four-engine heavy bombers, radar, and more—and for those achievements alone, his own country, the United States, and the whole world owe him a huge debt of gratitude.

Originally published in the January/February issue of World War II magazine.