On April 9, 1865, Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. Lt. Col. Ely Parker, Grant’s military secretary and a Seneca Indian, recalled that Lee shook his hand and said, “I am glad to see one real American here.”

Parker replied, “We are all Americans.”

It’s a storybook ending to four nightmarish years, emphasizing Lee’s grace in defeat and Grant’s compassion in victory as the nation turned toward the task of rebuilding. For many Americans, Appomattox marks the end of the Civil War, and Parker represents the involvement of Native Americans in it. But the war’s real end came months later, an unheralded event outside any state borders, in Indian Territory.

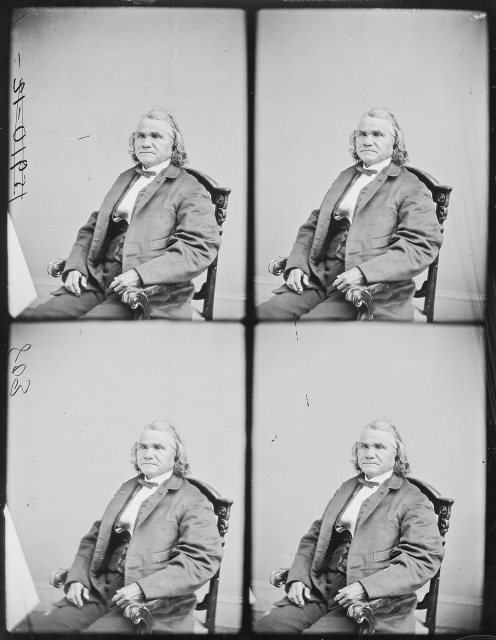

The man who surrendered there, on June 23, had never been an American citizen. He was Brig. Gen. Stand Watie, commander of the 1st Indian Brigade of the Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation in what is now Oklahoma. Watie had been fighting two civil wars — one against the United States and another against fellow Cherokees.

CHEROKEE WARS

The latter began more than three decades earlier. Watie, who was born in Georgia, was part of a small, unauthorized group of Cherokees who negotiated the 1835 Treaty of New Echota that ceded the Cherokee homeland in Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama and Tennessee to the United States for a promised payment of $5 million. In return, the Cherokees would be moved west of the Mississippi River and settled with the other tribes displaced from the Southeast — the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole.

Cherokee principal chief John Ross, duly elected by the National Council under the tribe’s constitution of 1827, represented the vast majority of Cherokees, who opposed removal. Watie, by contrast, regarded most Cherokees as poorly informed on the issue and felt justified in acting in what he interpreted as the people’s best interest, even if it was contrary to popular will. Many Cherokees, especially those who lost friends and relatives on the thousand-mile Trail of Tears during the brutally cold winter of 1838-39, never forgave Watie and his cohorts, three of whom were murdered by Ross supporters.

One of those killed was Watie’s brother Elias Boudinot (who had adopted the name of a New Jersey statesman and Indian rights advocate). As Watie sought vengeance, personal disputes took on political meaning and common criminals took advantage of the situation. Te resultant turmoil in the Cherokee Nation lasted eight years. Finally, in August 1846, the warring parties signed a treaty that brought an uneasy peace. Ross and Watie shook hands, but their animosity continued to simmer.

Despite their opposing positions, Ross and Watie had much in common. Both spoke English and had some formal education — Ross with tutors and Watie in mission schools. Both owned plantations and slaves before and after removal. Both were engaged in commerce: Ross and his brother won the contract to provision Cherokees on their trek west; Watie ran his own store. But the tragedy of removal set the two men on separate paths that further diverged as the Civil War began.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

THE CIVIL WAR LOOMS

The Cherokee Nation could not ignore the impending storm because its law recognized and protected slavery. It was longstanding Cherokee practice to hold war captives in a kind of bondage. But in the 1790s, the United States began promoting commercial agriculture in an effort to “civilize” the Indians, and Cherokees with capital invested in African American slave labor, just like their white Southern neighbors. By the time of removal, Cherokees held 1,592 African-American slaves; in 1860 the number stood at 2,511, or 15 percent of the total Cherokee population.

Fewer than 3 percent of Cherokees actually held slaves, but the rest did not actively oppose slavery until war threatened. Encouraged by antislavery missionaries, some non-slaveholding Cherokees joined the Keetoowahs, or “Pins” (for the crossed pins they wore under their jacket lapels), a group of cultural traditionalists. As pro-secession Cherokees became more active, the Pins became more overtly pro-Union and antislavery.

John Ross addressed the division in a speech to the National Council on Oct. 7, 1860, in Tahlequah, the capital of the Cherokee Nation. With slave-holding states to the east and south of the Cherokee Nation and slaveholders among the Cherokees, he acknowledged, “Our locality and situation ally us to the South.” But from the North came the “defense of our rights in the past and that enlarged benevolence to which we owe our progress in civilization,” that is, the Union had once protected Cherokee lands and supported missions. Therefore, Ross proclaimed, the only feasible solution was for the Cherokee Nation to honor its treaties with the United States and remain neutral.

Watie disagreed. He fanned anti-Union sentiment by spreading unfounded rumors — such as the imminent replacement of Southern, pro-slavery Indian agents with abolitionist supporters of the new Republican Party — and organized the pro-Confederate Knights of the Golden Circle. Most of his followers were slaveholders, but many non-slaveholders sided with the Confederacy because of their memories of the removal conflict and resentment of Ross’ power as principal chief. One Watie supporter wrote that the secession crisis provided his allies with an opportunity to defeat “this old Dominant Party that for years has had its foot upon our necks.”

CONFEDERATE CHEROKEES

In the winter and spring of 1861, Indian nations neighboring the Cherokee signed treaties with the Confederacy, Arkansas and Texas seceded from the Union and Federal troops withdrew from Indian Territory to Kansas, leaving the Cherokee Nation vulnerable to invasion. In July, Watie began enlisting recruits in the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles, a Southern cavalry battalion. By August Ross had concluded that a Confederate alliance was unavoidable, and in October the Cherokee Nation signed a treaty with generous terms. The Confederate government agreed to let the Cherokees sell parcels of land in Indian Territory, something the United States had refused to do. The treaty also guaranteed Cherokee investments and annuities. Finally, the Confederates offered the Cherokees a representative in the Confederate Congress, something the United States never even contemplated. (Watie’s nephew Elias Cornelius Boudinot was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives and served until the end of the war.)

Ross commissioned another prominent Cherokee, John Drew, to raise a regiment — separate from Watie’s battalion but also named the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles — to defend the Cherokee Nation and serve the Confederacy. When the Confederates formed the Trans-Mississippi Department in 1862, both Watie and Drew received the rank of colonel and Watie’s unit became the 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles. All were in the Confederate Army, but Watie’s and Drew’s soldiers differed dramatically. Watie’s men were pro-slavery and ardent Confederates. Some members of Drew’s regiment were abolitionists, and others, including Drew, were slaveholders, but most were ambivalent about slavery and their military service. One antislavery Baptist missionary to the Cherokees described these nominal Confederates as “decidedly loyal Union men.” Their first military engagements validated his view.

Neighboring Creeks and Seminoles, like the Cherokees, were divided over the issue of a Confederate alliance and the Union sympathizers came to be known as “Loyal Creeks.” In fall 1861, some 2,500 of these Indians along with several African Americans assembled at the plantation of the Creek headman (and slaveholder) Opothle Yoholo and headed north for the Union state of Kansas.

FRATERNAL FIGHTING

On Nov. 19, Choctaw and Chickasaw soldiers under Confederate colonel Douglas Cooper found the Creek camp at Round Mountain in the Creek Nation, but the Loyal Creeks drove the Confederates back and covered their retreat with a grass fire. More than 100 Creeks died, but all of the survivors escaped.

Although they had few supplies, the Loyal Creeks struggled north in deteriorating weather. On Dec. 9, a bloody skirmish at Chusto-Talasah with Col. Drew’s 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles cost the Loyal Creeks as many as 500 men. But the cost for the Confederates was also high: Many of Drew’s soldiers deserted. Some joined Opothle Yoholo’s fight to Kansas while others simply went back to the Cherokee Nation.

A third attack, at Chustenahlah on Dec. 26, killed approximately 250 Loyal Creeks, and nearly 200 women and children were captured. Colonel Watie arrived at the end of the battle and pursued the Creeks, killing approximately 100 more. When Opothle Yoholo and his followers finally made it to Kansas in early 1862, they were half-frozen and starving. The U.S. Army did little to help them, and conditions in their camps were deplorable.

“I was prepared to see a set of poor, needy, and dependent creatures, but, sir, history will never correctly chronicle the extreme suffering of these Indians,” a special agent to the refugee Indians reported to the commissioner of Indian Affairs in February.

Nevertheless, every day more Indians loyal to the Union arrived. Another Indian Affairs agent noted that more than 2,000 men, women and children, “entirely barefooted … [with] not rags enough to hide their nakedness,” had relocated to Kansas, and the carcasses of as many as 1,500 dead ponies threatened the refugees’ already precarious health.

Scalping DESERTERS

Back in Tahlequah, Ross permitted Drew’s defecting officers to resign their commissions and granted amnesty to other deserters. The Confederacy made no effort to court-martial any of them, but Watie was not as forgiving. Among other incidents, Watie’s nephew killed and scalped a deserter from Drew’s regiment who, Watie claimed, had been “hostile to southern people and their institutions.” Tis act was merely a harbinger of the brutality to come. Watie’s wife, Sarah, wrote that the reports of atrocities “almost runs me crazy,” despite her belief that Unionists “all deserve death.”

Watie’s men and what was left of Drew’s regiment saw action again in March 1862, when Brig. Gen. Albert Pike, who had negotiated the Cherokee treaty with the Confederacy, led the Cherokees into Arkansas to counter a Union invasion. Although the Confederates lost that engagement, the Battle of Pea Ridge, the Cherokees initially distinguished themselves by routing two companies of the 3rd Iowa Cavalry and capturing three cannons. In the aftermath, however, the Cherokees scalped at least eight Iowans. Pike resigned his commission and faced a court-martial. The individuals responsible for the act were never identified, but the incident unleashed a torrent of negative press in the North protesting the Confederacy’s use of “Aboriginal Corps of Tomahawks and Scalpers” against the United States.

NORTHERN NATIVE AMERICAN FORCES

The Union Army, however, soon came to rely on Indian forces of its own. In May 1862 the Indian Home Guard organized in Kansas to drive out Confederates, and in June, the Home Guard joined a Union foray into Indian Territory. At Cowskin Prairie, Cherokee Nation, on June 6-7, they forced the retreat of Watie’s troops. A more substantial victory came on July 3, when U.S. forces, including 1,600 Indians, captured more than 100 Confederates as well as mules, wagons, ammunition, clothing and other supplies at Locust Grove. At Bayou Menard, on July 27, they defeated Watie again. Encouraged by these victories, 1,500 new recruits joined the Home Guard and formed two additional regiments, one of which comprised 600 former Confederates who had served under Drew.

The desertion of so many Cherokees from Drew’s command, Ross’ leniency and Cherokee enlistments in the Home Guard gave credence to the view that most Cherokees were pro-Union and that Chief Ross had been forced into a Confederate alliance. But when Union troops arrived in Tahlequah on July 15, Ross initially refused to meet with them out of respect for the Nation’s existing treaty with the Confederacy. They took the chief captive and retreated to Kansas with Ross, his family and the records and treasury of the Cherokee Nation. Ross was soon paroled and spent the rest of the war in Philadelphia and Washington pleading for the compassionate treatment of the Cherokees when the war ended.

RIPPING UP THE CONFEDERATE TREATY

Tomas Pegg, president of the Cherokee National Council, became acting principal chief. Previously a major in Drew’s regiment and probably a Keetoowah, Pegg also had served as a captain in the 3rd Indian Home Guard. Under his leadership, in February 1863 the Cherokee National Council revoked the Confederate treaty, deposed members who still supported the Confederacy and emancipated all slaves within the Cherokee Nation.

Col. Watie could not countenance such a move. After Ross’ capture and parole, he declared the office of principal chief vacant, appointed himself to the position and banned pro-Union public servants. The Cherokees now had two governments — one constitutionally elected and pro-Union, the other self-proclaimed and pro-Southern. The latter promptly drafted all men between 16 and 35 into the Confederate Army and sent its soldiers to round up or kill men who avoided the draft. As a result, thousands of pro-Union Cherokees went into hiding or fed to Missouri or Kansas.

Abandoned

Many of those who left followed the Union troops from Tahlequah because, as some observers wrote to Ross, “they had been robbed of all their means of subsistence, & their lives threatened.” These Cherokees ended up first in a camp in Kansas, which they described as “literally a grave yard.” The Army then relocated them 120 miles to Missouri where they had adequate food and shelter but no clothing. When the Army sought in 1864 to move them yet again, they refused, whereupon the U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs, they charged, “abandoned the care” of the Indians entirely.

Those who remained behind in the Cherokee Nation suffered as well. Confederate guerrillas such as William Clarke Quantrill sporadically preyed upon them. One Cherokee recalled that they drove his mother “out of the house and set fire to it, and burned the furniture, clothes, and everything.”

Fellow Cherokees, however, presented a more constant danger. Hannah Hicks, a widow with five small children, wrote in her journal: “We hear today that the ‘Pins’ are committing outrages on Hungry mountain and Flint, robbing, destroying property & killing. It is so dreadful that they will do so. Last week, some of Watie’s men went and robbed the Rosses place up at the mill; completely ruined them. Alas, alas, for this miserable people, destroying each other as fast as they can.”

Cherokee slaves also were victims of this internecine violence, sometimes perpetrated by Cherokees who regarded slaves as a major cause of the war. In the 1930s, former slave Chaney Richardson recalled that Cherokee masters worried about “getting their horses and cattle killed and their slaves harmed.” Because her master owned three or four families, “them other Cherokees keep on pestering his stuff all the time.” Ultimately, Richardson’s mother was a victim. While she was collecting bark to set dyes, “somebody done hit her in the head and shot her through with a bullet too.” As Confederate fortunes shifted, some masters sold their slaves rather than risk total loss of their investment, and at least one slaveholder killed his elderly slaves rather than continue to feed them.

UNfriendly home

It was becoming increasingly difficult for Watie to operate within the Cherokee Nation. In April 1863, Federal troops occupied Fort Gibson and routed Watie’s men at Webbers Falls. On July 1-2 at Cabin Creek, Union troops fended of the Confederates as they attempted to capture a Union supply train bound for the fort. Confederate forces mobilized to retake the fort on July 17, but the Federals met them at Honey Springs in the Creek Nation and dealt the Confederates a resounding defeat.

To protect themselves and their slave property, some Confederate families, including that of Colonel Watie, moved south to the Choctaw Nation or to Texas. Life was hard. In December 1863, Watie’s wife, Sarah, wrote to him from Rusk, Texas, that she “had not a scrap of meat or grease … fit to use” and that all but two of her children were “bare of clothing.”

For slaves, conditions were far worse. Sarah Wilson recalled that her Cherokee master, Ben Johnson, “hired the slaves out to Texas people because he didn’t make any crops down there and we all lived in kind of camps.” Some families, including the Waties, took only the slaves they thought would be useful in Texas. In the process, they broke up families and left the most vulnerable in Indian Territory. The majority of Confederate refugees and their slaves spent at least two years in camps.

Chaos Reigns

Although the Union nominally controlled Indian Territory north of the Arkansas River after the summer of 1863, Confederate attacks continued, as did general lawlessness. Many Cherokees and African Americans took refuge at Fort Gibson, which had become a tent city where disease, including cholera, flourished. Supplying the fort and its civilian population was difficult. Since feeding the military was first priority, Chief Ross’ son wrote his father, women refugees had to “pick up the scattered corn from where the horses and mules had been fed.” The conditions at Fort Gibson and at the refugee camps in Kansas and Missouri led the chief to devote much of his time to raising funds for their relief.

In 1864, the Confederates enjoyed some success in Indian Territory. On June 15, as the vessel J.R. Williams, loaded with supplies, steamed up the Arkansas River toward Fort Gibson, Watie’s troops opened fire, destroying the smokestack and boiler. Watie reported that his men captured “150 barrels of four, 16,000 pounds of bacon, and [a] considerable quantity of store goods, which was very acceptable to the boys.”

But the haul created another problem: “Greater portions of the Creeks and Seminoles immediately broke off to carry their booty home.” In September at Cabin Creek, Confederates took a Union supply train headed for Fort Gibson, relieving their own privation while intensifying that at the fort. “I thought I would send you some clothes,” Sarah Watie wrote to her husband, “but I hear that you have done better than to wait on me for them.”

That same month, Watie’s command surprised a group of soldiers that included troops from the 79th U.S. Colored Infantry who were cutting hay for livestock at the fort. Instead of accepting the surrender of the African Americans, the Confederates killed 40 of them. Such exploits earned Watie promotion to brigadier general, but his successes in the final year of the war did nothing to change the outcome.

THe End, AND AFTER

On April 9, Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia.; over the next two months, as rumors swirled that Watie’s troops were preparing for an attack on Kansas, the western Confederate armies also laid down their arms. Finally, on June 23, the war came to an official, and quiet, end. Brig. Gen. Stand Watie signed a treaty agreeing to cease hostilities and to have his troops “return to their respective homes, and there remain at peace with the United States.”

Nevertheless, in the Cherokee Nation, as in the United States, acrimony long endured. Perhaps as many as 8,000 men from Indian Territory fought for one side or the other during the war, but most of the 10,000 people who died were refugees. A substantial proportion were Cherokees, and those who survived returned to find their homes and farms in ruins. It is estimated that one in four Cherokee children was an orphan and one in three Cherokee women a widow. By some accounts, the Cherokees were in worse straits after the Civil War than they had been after removal from their homeland 30 years earlier.

Immediately after the war, the United States declared that the Cherokee Nation had forfeited all rights under previous treaties, and it refused to recognize Ross as principal chief. Furthermore, U.S. peace commissioners seemed much friendlier toward the Confederate Cherokees than they were toward the Unionists, largely because that wing favored land grants for railroad construction through Indian Territory.

Former Union and Confederate supporters, including Stand Watie, traveled to Washington, D.C., for negotiations. Although the United States had fought to preserve its Union, the postwar federal government sought to permanently divide the Cherokee Nation. President Andrew Johnson supported a treaty that created a separate Southern Cherokee Nation, but Ross, who was in failing health, argued persuasively against it. On July 19, 1866, after Watie had returned west, Ross prevailed with a treaty that kept the Nation intact while it restored property to Southern Cherokees and permitted former Confederates to move into a district between the Canadian and Arkansas rivers. Former Union and Confederate supporters, including Stand Watie, traveled to Washington, D.C., for negotiations. Although the United States had fought to preserve its Union, the postwar federal government sought to permanently divide the Cherokee Nation. President Andrew Johnson supported a treaty that created a separate Southern Cherokee Nation, but Ross, who was in failing health, argued persuasively against it. On July 19, 1866, after Watie had returned west, Ross prevailed with a treaty that kept the Nation intact while it restored property to Southern Cherokees and permitted former Confederates to move into a district between the Canadian and Arkansas rivers. Upon Ross’ death, the National Council voted for his nephew, W.P. Ross, to succeed him as principal chief. Watie’s followers feared reprisals, and old enmities soon came to the fore, Arkansas rivers. The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty on July 27; five days later, on August 1, Ross died.

OLD GRUDGES

Upon Ross’ death, the National Council voted for his nephew, W.P. Ross, to succeed him as principal chief. Watie’s followers feared reprisals, and old enmities soon came to the fore, but most Cherokees had had enough conflict. In 1867, Lewis Downing, a Pin who chose to speak only Cherokee and who had served in the 3rd Indian Home Guard, was elected principal chief on a platform of national reconciliation. Stand Watie and his family, who had been living in the Choctaw Nation, returned to the Cherokee Nation and rebuilt their home at Honey Creek, where they had settled after the removal. He died there in 1871.

The Cherokee Nation continues to debate issues rooted in the Civil War and its aftermath. The 1866 treaty that technically put the Nation back together also emancipated its slaves and granted those freedmen “all the rights of native Cherokees.” An amendment to the tribal constitution made all former Cherokee slaves resident in the nation by Jan. 19, 1867, “citizens of the Cherokee Nation.” But the role of descendants of former slaves in the Nation remains a contentious issue.

In March 2007, the Cherokees approved a constitutional amendment to exclude from citizenship descendants of freedmen who were not listed as “Cherokees by blood” on the official tribal roll. The question is, does their exclusion violate the treaty of 1866? A legal case arising from this vote made its way before the U.S. District Court in Oklahoma . Slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction laid the groundwork for this controversy, just as removal contributed to Cherokee engagement in the Civil War.

Theda Perdue is Atlanta Distinguished Professor Emerita of Southern Culture, History and American Studies at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She is the author or editor of 15 books, primarily on American Indians.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.