Lumbering was the key to mining profitability.

In 1875 the Comstock Lode was still pouring out its riches in Virginia City, Nevada. Timber was a precious commodity for the mines and the only source was the Sierra Nevada, dozens of miles away. The Bonanza firm had just built a 15-mile-long V-flume that extended from its 12,000-acre timber tract on the high slopes of the Sierra Nevada to Huffakers Station on the Virginia & Truckee Railroad, in present-day Reno. Two of the tycoons to emerge from the Comstock Lode, James C. Flood and James G. Fair, principals of the Bonanza firm, decided to baptize their newly completed flume with a ride down the mountain.

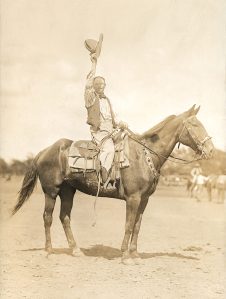

H.J. Ramsdell, a reporter for the New York Tribune, was “lucky” enough to get invited along. Ramsdell found himself atop the 15-mile run in a makeshift flume boat—little more than a “pig trough with one end knocked out,” 16 feet long and V-shaped like the flume. The men embarked in two boats: Fair, Ramsdell and a “volunteered” carpenter in the front boat, and Flood in the rear boat with John Hereford, the contractor who built the flume. Ramsdell was reluctant but reasoned that “if men worth 25 or 30 million apiece could afford to risk their lives, I could also afford to risk mine, which is not worth half as much.”

Shooting down trestles as high as 70 feet, Ramsdell was terrified: “You cannot stop; you cannot lessen your speed; you have nothing to hold to; you have only to sit still, shut your eyes, say your prayers, take all the water that comes —filling your boat, wetting your feet, drenching you like a plunge through the surf—and wait for eternity.” At one point, the first boat hit a submerged object, hurling the carpenter out the front of the boat into the flume itself. Fair yanked him back in. Then, near the end of the run, the second boat caught up and rammed the first. The impact flattened both boats, but their waterlogged riders hung on. When the wreckage finally slowed at the base of the mountain, they jumped clear of the flume.

According to Ramsdell, Fair said, “I will never again place myself on an equality with timber and wood,” while Hereford said, “I am sorry I ever built the flume.” Fair estimated, “We went at a mile a minute.” But as Ramsdell summed it up, “My deliberate belief is that we went at a rate that annihilated time and space.”

Other flume riders were less fortunate; death and serious injury were common outcomes. Some flume companies forbade flume riding, but at the end of a six-day workweek, a Saturday night ride down the flume to waiting pleasures in the valley was a tempting prospect. The V-flume provided a rush while furthering the fortunes of the Comstock Lode.

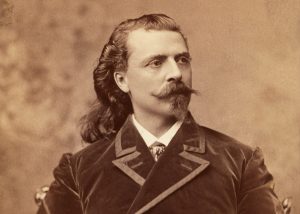

Prospectors en route to California had discovered gold in western Nevada around 1850—enough dust and ore to keep them busy for the next decade. In 1859 several prospectors, including James “Old Virginny” Finney and Henry Comstock, were digging on the eastern slope of Mount Davidson and found “blue stuff” that turned out to be extremely high-grade silver ore. Thus began one of the richest mineral discoveries in U.S. history.

During one drunken celebration, so the story goes, Finney accidentally broke a bottle of whiskey and watched it spill into the desert sand. He used the precious liquid to christen the new settlement “Old Virginny Town.” In 1859 the settlement officially became Virginia City, while the strike itself became known as the Comstock Lode. In 1873 four investors opened a huge ore body of vast richness named the Big Bonanza. The mine made them tycoons.

The original strike area became the Ophir and was the first mine to encounter problems with the loose, crumbly ore body. At a depth of 50 feet, the shaft was 10 to 12 feet wide, but by the time it reached the 180-foot level, it was 40 to 50 feet wide. Local timber sources were short, scrubby trees. Miners had to splice together the resulting timbers with iron bolts and bars. Even then, the frames couldn’t handle the pressure of the constantly shifting earth. The superincumbent “blue stuff” had rendered the shafts unstable and dangerous.

In 1860 German engineer Philip Deidesheimer, inspired by a honeybee’s comb, invented square-set timbering— a framing system that used interlocking rectangular timber sets to support the unstable rocks. Filled with waste rock to form support pillars, the finished structure resembled a honeycomb. So much timber was used in its construction, it was said “a forest of underground timbers of enormous dimensions” lay under Virginia City. Eventually, the constant pressure of moving earth worked on even the stoutest timbers, compressing wood that was originally 14 inches thick to a thickness of 2 to 3 inches. The tremendous pressure made it, as one tongue-in-cheek report had it, “as easy to cut as if it were so much iron.” Locals called it petrified wood.

Over the next 20 years, the Comstock Lode consumed 600 million board feet of lumber for the mines and 2 million cords of firewood to run steam engines in the mines and mills. Author William Wright (aka Dan De Quille) gave a firsthand account of the situation on the Comstock in 1876: “The Comstock Lode may truthfully be said to be the tomb of the Sierras. Millions upon millions of feet of lumber are annually buried in the mines, nevermore to be resurrected. When once it is planted in the lower levels, it never again sees the light of day. …For a distance of 50 or 60 miles, all the hills of the eastern slope of the Sierras have been to a great extent denuded of trees of every kind; those suitable only for wood as well those fit for the manufacture of lumber for use in the mines.”

With timber near Virginia City in short supply, miners turned to the “unlimited” Sierra Nevada timber, harvesting trees on the lower slopes. Deidesheimer’s squareset timbering made the mines safe, but it would take a second monumental invention to get the wood out of the mountains. Enter the flume.

In the steepest reaches, loggers constructed gravitation flumes that didn’t use water. Placed in the chute, the logs slid down faster than speeding trains, sometimes leaving a trail of smoke and fire. These chutes emptied into lakes to keep their cargo from being “shivered to pieces.” On occasion a daring logger would slide down a gravitation chute, ending with a “wild leap of 20 or 30 feet into the lake”—if he was lucky.

When operations moved deeper into the Sierras, sawmills often occupied upper-elevation staging areas and sent large volumes of lumber down the flumes. As early as 1854 on the Sierra Nevada, U-shaped water flumes had been used to transport lumber downhill. U-flumes, typically 4 feet wide at the bottom, 5 feet wide at the top and 32 inches in depth, did not work well, as the lumber often became lodged, causing costly overflows and washouts.

James W. Haines is commonly credited with constructing the first successful V-shaped flume in the Sierras, in 1867. The V-flume avoided overflows with its simple construction: two boards joined at a 90-degree angle, supported by a trestle on a downward slope, partway filled with flowing water. If timber got caught in the V-flume, water would back up, elevate the wood and release it. It could carry sawn timber 16 inches square and up to 40 feet long rapidly and economically down the mountain.

The first V-flume associated with Haines ran 32 ½ miles from Alpine County, Calif., to Empire City, Nev., and connected there via rail to the Comstock. Firms profiting from the Comstock Lode market for timber quickly embraced the new technology. In his 1879–80 industry report, Nevada’s surveyor general recorded 10 major flumes with a combined length of 80 miles transporting 33.3 million board feet of lumber and 171,000 cords of wood.

No mining report of the period was complete without mention of water and timber availability. Square-set timbering and the V-flume were foundational to Western mining.

Originally published in the August 2010 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.