Imagine a situation in the modern American army where officers refuse to fight under other officers, where generals openly defy and even strike their superiors, where officers are cashiered or relieved of command at a whim, where dueling challenges are routinely issued and accepted with no fear of official censure or retaliation.

Such a detrimental state of affairs would never be tolerated by either the civilian leadership or the military high command. Yet, this was precisely the situation that existed in Civil War armies on both sides, although the Confederate Army suffered more from its consequences.

The Confederate officer corps was a collection of highly individualistic, temperamental and ambitious men. Honor and personal pride seemed to be at the root of most of their personal differences with each other, even to the point where these considerations were placed above the best interests of the Confederacy. These differences affected military decisions, strategic planning and campaign operations throughout the war and contributed greatly to the eventual demise of the Confederacy.

The Confederates began bickering among themselves at the first important battle of the war. At the Battle of Manassas, the oversized egos of Generals Joseph Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard were found to be too large for the same battlefield. In a dispute that was to be repeated again and again during the war, they argued over who should command their combined forces. Unfortunately for Beauregard, his opponent was better armed for the debate, having brought along a telegram from Southern President Jefferson Davis strictly establishing the relationship between them. Specifically, Johnston’s commission made him a full general, while Beauregard was only a brigadier general. Therefore, Johnston officially commanded their forces that day.

However, the wily Creole got in the last word; while Johnston napped in his tent after his long train ride from the Shenandoah, Beauregard drew up the battle orders, to which he attached his name. Later he awoke Johnston to have the commanding general cosign under Beauregard’s name. Wanting to avoid argument, or perhaps too sleepy to notice, Johnston signed, and history gave Beauregard the credit for the first great battlefield victory of the war.

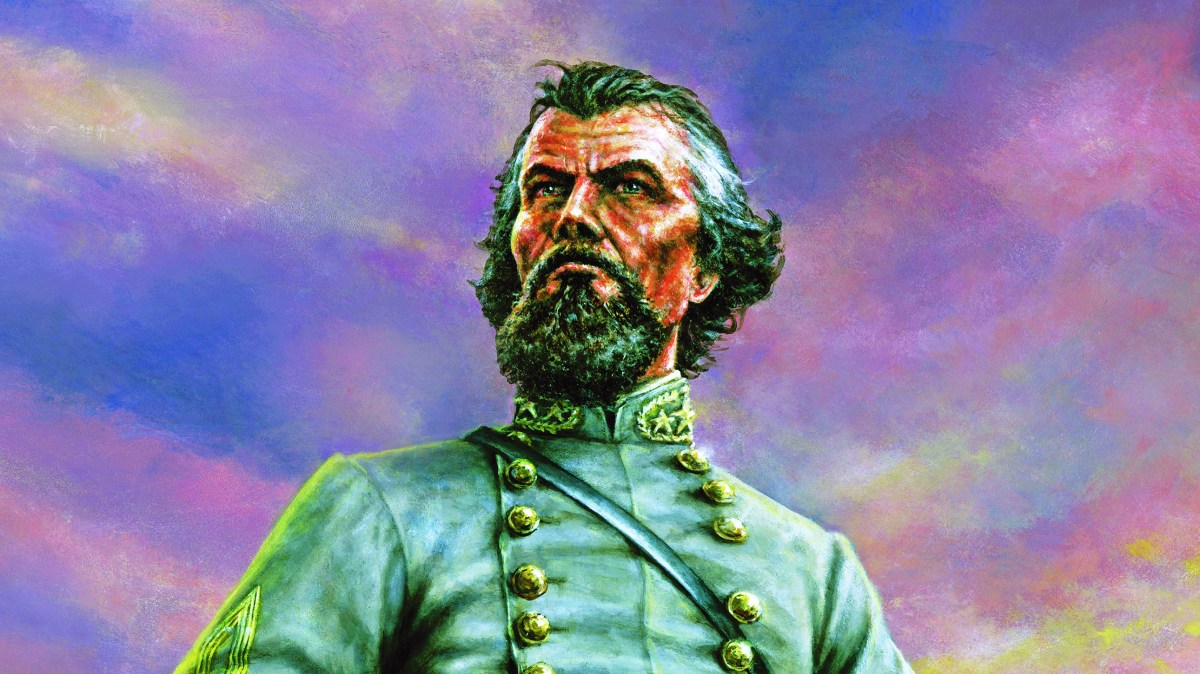

Other disputes on the Confederate side were neither as harmless nor as fortunate in their outcome. Some, indeed, became legendary, such as those involving the fearsome cavalry leader Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest was a bear cat for a fight. He once gutted one of his lieutenants with a pocketknife after the disgruntled officer had first shot the general. Such a man was not to be trifled with lightly.

On two different occasions, Forrest insulted superior officers in the bluntest terms, and probably only his lethal reputation as a duelist prevented them from taking action. On the first occasion, Forrest resented being placed under Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s command in 1862 and, when Wheeler committed their troopers to an ill-conceived attack on Fort Donelson in early 1863, Forrest flew into a rage. He told Wheeler, “This is not a personal matter, but you will tell General Bragg in your report that I will be in my coffin before I will fight under you again.” (If it had been a personal matter, Forrest probably would have just shot Wheeler and been done with it.) Forrest then ended his tirade with the ultimate military gesture of protest: “If you want my sword, you can have it.”

Later in the war, Forrest told General Braxton Bragg just what he thought of that vacillating, indecisive officer after Bragg had twice “tampered with” Forrest’s cavalry command. The confrontation occurred at Bragg’s headquarters on Missionary Ridge during the ridiculous Confederate siege of Chattanooga. Forrest said: “I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to. You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your jaws and force you to resent it…. If you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path, it will be at the peril of your life.”

Major General A.P. Hill, one of Virginia’s favorite sons, was also known for his fiery temper. One historian calls him “probably the most contentious of the Army of Northern Virginia’s officers.” Hill quarreled with every officer he served under. After the Seven Days’ Battles, he engaged in a war of newspaper releases with Maj. Gen. James Longstreet over who deserved the most credit for the successfully completed campaign. After several volleys in the Richmond Whig and Richmond Examiner, Hill cut off all communications with Longstreet’s headquarters and demanded to be relieved from serving under Longstreet.

For his part, Longstreet heartily endorsed the request, adding a sardonic note that it was necessary “to exchange the troops or to exchange the commander.” When commanding General Robert E. Lee delayed taking action, the feud only grew worse. After Hill’s refusal to forward even routine reports to headquarters, Longstreet placed him under arrest and confined him to quarters. Hill took the next step, issuing a challenge to his commanding officer to duel. The two men began making arrangements to settle their differences on the field of honor.

The possibility of losing one or both of his finest commanders finally moved Lee to take action. He restored Hill to his command, then transferred his division to Stonewall Jackson’s corps in the Shenandoah Valley. The friendship between Hill and Longstreet was shattered beyond repair, and their relations henceforward were no better than “coldly courteous.” Lee had merely rearranged his problems, not solved them. Within a week, Hill and Jackson were squabbling, this time over Jackson’s uncommunicative command style and their differing interpretations of military protocol. That feud soon surpassed the Longstreet-Hill feud.

On the march into Maryland in the late summer of 1862, Jackson finally grew so exasperated with Hill’s failure to follow his prescribed marching orders that he rode to the head of Hill’s division and began personally issuing orders to Hill’s brigadiers.. At this moment, Hill galloped up and addressed Jackson in high dudgeon: “General Jackson, you have assumed command of my division, here is my sword; I have no use for it.” Jackson calmly replied, “Keep your sword, General Hill, but consider yourself under arrest for neglect of duty.”

For the rest of the advance, Hill was ordered to march in the rear of his division. Jackson’s charges against Hill were not for insubordination, as one might expect, but for allowing his command to straggle, a fine distinction, perhaps, that was lost on Hill.

Although Hill was restored to command before the campaign was over, and later fought magnificently, he did not forget or forgive. He preferred charges of his own against Jackson. The charges and countercharges persuaded Lee to step in again, this time to call a peace conference of the principals in order to defuse what was tepidly building toward an explosion that would have been extremely damaging to the Confederacy. The peace conference settled nothing, and the charges were still pending when Jackson was killed at Chancellorsville the next spring.

Jackson himself was a legendary feudist, even more obstreperous than Hill, if such a thing could be. At one time or another, he placed Turner Ashby, Richard B. Garnett and Hill all under arrest and ordered their courts- martial?and this was a man who died before the war was half over. On another occasion, he placed five of A.P. Hill’s colonels under arrest for letting the men use a fence for firewood. Jackson was chronically unable to get along with subordinates, in contrast to Hill, who was chronically unable to get along with superiors.

In the summer of 1861, Jackson began court-martial proceedings against a number of his officers. He blamed Garnett, commander of Jackson’s old “Stonewall Brigade,” for the defeat at Kernstown, and that was just the beginning. Other officers were brought up on charges ranging from insubordination to cowardice under fire. Jackson pressed so many charges that, at one point, all of his subordinate officers were on courtmartial duty.

Garnett’s court-martial for “unauthorized retreat” began in August 1862, but was never settled because the war intervened. Jackson was killed at Chancellorsville, and there are those who say that Garnett went to his death at Gettysburg a few months later in Pickett’s Charge glad for the opportunity to vindicate his besmirched honor.

As for Ashby, he was also reprimanded by Jackson after the Battle of Kernstown for the “undisciplined state of his cavalry.” The proud Ashby briefly considered challenging Jackson to a duel, but shooting the sanctimonious Stonewall did not seem sufficient to assuage his wounded pride. Instead, he announced his intention to leave the army. When word of this got out, his troopers announced they would follow Ashby out of the army rather than serve under anyone else. Faced with a mutiny of major proportions, Jackson backed down for the first and last time in his life. He restored Ashby to full command.

Jackson even quarreled with the sainted Lee on one occasion. In December 1862, he reacted angrily to Lee’s request that he transfer some of his artillery to other commands not so well equipped. Lee did not force the issue. It had been conjectured that the subsequent lack of communication between Lee and Jackson during the Seven Days’ Battles was at least partly because the two proud leaders felt a sense of rivalry and bent over backward to avoid stepping on each other’s toes.

As serious as the situation was in the Army of Northern Virginia, it was nothing compared to the situation in the Western armies. The surrender of Fort Donelson offers a case study in how to lose a campaign through jealousy and infighting. The Confederates began the campaign for the Tennessee River at a disadvantage because they were attempting to fight with a divided command. Brigadier General John Floyd, a former secretary of war, was the senior officer at Fort Donelson in February 1862, when Union forces under U.S. Grant initially besieged the fort. However, when Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow arrived from Columbus, Ky., he immediately assumed command with no other authority than his own presumptuousness. Simon B. Buckner’s arrival on the night of February 11, 1862, put a third brigadier on the scene. From that point on, there was a definite lack of cooperation among the Confederate high command responsible for holding Fort Donelson.

Pillow and Buckner were already enemies from before the war, when Buckner had blocked Pillow’s ambition to become a US. senator from Tennessee. Old insults were not easily forgotten, even in the face of a common enemy, and their mutual hostility was hardly kept under wraps. The fact that Pillow was a take- charge kind of person, in a situation calling for tact and diplomacy, did not help. The 55-year-old Floyd might have served as a counterweight to the other two, but he was totally under Pillow’s influence despite his own impressive credentials.

While the three generals struggled to mount an effective defense of the vital fort, Grant tightened the noose. By February 15, a mood of defeatism had infected the Confederate side. That night there occurred one of the most amazing examples of a cumulative collapse of will in the annals of American warfare. The three generals held a council of war to decide on a course of action. Should they fight, retreat or surrender? Floyd and Pillow decided to surrender.

Having decided the fort could not be held, Pillow and Floyd then refused to surrender it personally to Grant. They feared they might be confined in a Yankee prison for the duration of the war, or worse, hanged as traitors. They turned the onerous task over to Buckner in the following famous exchange:

Floyd: “I turn the command over, sir.”

Pillow: “I pass it.”

Buckner: “I assume it.”

Several ironies resulted from this military fiasco. Although President Davis initially relieved Floyd and Pillow from command, the Southern press at first hailed them as heroes for refusing to surrender and castigated Buckner for turning over the keys to the fort and the Tennessee River. Pillow later was restored to command. Meanwhile, Buckner, arguably the best officer of the three, was marched off to a Northern prisoner- of war camp.

The Army of Tennessee had more than its share of general feuds, which usually seemed to start at the top with the general commanding. During his tenure at the head of the Army of Tennessee, Braxton Bragg made history by single-handedly setting military science and personnel management back to the Stone Age. It was Bragg, one should remember, who once got into an argument with himself while commanding a frontier post and serving at the same time as post quartermaster. Such a background did not bode well for a man who was expected to control a collection of temperamental, quarrelsome lieutenants against a superior enemy in a vast, sprawling theater far from Richmond’s authority.

Bragg quarreled, at some point, with everybody who served under him. It was not just that his cold, imperious manner offended everyone; he also displayed appalling incompetence, which only he failed to discern. Long before Forrest became fed up with Bragg and told him so to his face, other general officers had reached the same conclusion, although they expressed their opinions with more circumspection.

Bad feelings first surfaced during the Murfreesboro campaign, when Bragg’s two corps commanders, Leonidas Polk and William Hardee, refused to visit headquarters except as required by necessity, and even then they kept their visits as short as military matters permitted. It is doubtful that the men in the ranks failed to sense the cool relations between their senior officers.

After the Battle of Stones River, a strategic reverse for the Confederacy, Bragg took the highly unusual step of canvassing his officers to ask for their frank assessment of his leadership. All his division commanders advised him to resign immediately. Polk even wrote a personal letter to Jefferson Davis asking that Bragg be relieved. It was no coincidence that shortly thereafter Bragg placed Polk under arrest for his conduct in the recent battle and forwarded formal charges against him to Richmond. Davis, who considered both Bragg and Polk personal friends, refused to take action, and the charges were dropped. Worse still, Polk stayed with the army.

Bad news travels fast, and when Longstreet in Virginia heard of the problems in the Western army, he dashed off a letter to Secretary of War James Seddon making a thinly veiled offer to take Bragg’s place, because “I doubt if General Bragg has the confidence of his troops.” He also added, disingenuously, “I am influenced by no personal motive.” Longstreet, who always coveted independent command, probably dreamed of escaping Lee’s immense shadow and expected to whip the Western army into the same sort of fighting trim as the Army of Northern Virginia.

It is doubtful that Longstreet ever felt comfortable in the designated role of Lee’s “Old Warhorse,’ a nickname Lee himself bestowed upon his lieutenant. Longstreet always saw himself in a grander role than his superiors allowed. On this occasion, Davis was not willing to put Longstreet in command, but he compromised by dispatching Longstreet and two of his divisions to Georgia after the Battle of Gettysburg to join Bragg’s army.

After Bragg snatched stalemate from the jaws of victory at Chickamauga, Longstreet took up the pen again, this time writing the secretary of war to request that Lee be sent west to replace Bragg. He seemed to have good cause this time? Bragg was busy cashiering senior officers like they were corporals and alienating those he did not dismiss. At the end of September 1863, he removed Generals Polk and Thomas Hindman, sending them to Atlanta to await further action from Richmond. Again, Davis intervened by ordering charges dropped.

The controversy swirling around Bragg was far from over. In fact, it was just climaxing in the famous “Round- robin Letter,” also known as the “Revolt of the Generals.” The dump-Bragg clique, now headed by Longstreet, was still hard at work. A letter was circulated among the senior officers of the army urging Davis to replace Bragg. When it finally reached the president’s desk, it bore the signatures of John C. Brown, William Preston, Leonidas Polk and D.H. Hill, among others.

The round-robin drawn up by Bragg’s senior officers was a devastating vote of no-confidence and secured the desired response from Richmond. Davis dropped all other matters and came to the army’s headquarters in person to investigate the problem. In a subsequent meeting called by Davis, the president polled the army’s senior officers for their opinions, while Bragg himself looked on uncomfortably. Longstreet, Hill, Benjamin Cheatham, Patrick Cleburne and Alexander Stewart all spoke up and said that Bragg was unfit for command and should be relieved. Only Lafayette McLaws defended Bragg, but his voice was drowned out in the chorus of naysayers.

Unfortunately for the Army of Tennessee, the majority opinion was not shared by the president of the Confederacy. With practically everybody wanting to get rid of Bragg except Davis, the decision to retain him in command was carried by “a majority of one.”

Longstreet continued to be a lightning rod for controversy in the West, and he apparently learned nothing from his experience in the Generals’ Revolt. His campaign against Knoxville was badly bungled in the winter of 1863 ; and he blamed his subordinates, specifically Brig. Gen. J.B. Robertson, commanding Hood’s Texas Brigade, and Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, one of his division commanders.

McLaws’ list of faux pas began when he sided with Bragg earlier against the Longstreet faction in the Generals’ Revolt. On that earlier occasion, Longstreet had criticized Bragg for blaming his military setbacks on his subordinates; ironically, he now found himself doing the same thing. On December 11, 1863, he sent a curt note to McLaws containing odd, third person references to himself and an even odder ultimatum that one of them had to go and, since the commanding general could not leave, McLaws had to be the one.

The charges against McLaws included neglect of duty, failure to instruct and organize his troops, and poor command decisions. Longstreet charged that McLaws had the poor judgment to “exhibit a want of confidence in the efforts and plans which the commanding general had thought proper to adopt.” The irony of this vague charge from the same man who at Gettysburg had opposed the “efforts and plans” of his commanding general, seemed not to have registered on Longstreet.

McLaws sought exoneration by insisting on a full court-martial, which was his right and, like most wartime courts-martial, this one dragged on for months, sapping the energy and distracting the attentions of all the officers involved. The court, in May 1864, delivered a guilty verdict on only one of the three principal charges and handed down a relatively light sentence of 60 days’ suspension. Davis immediately set the verdict aside and restored McLaws to full command. The president’s action put Longstreet in a bad light, besides reuniting two unhappy officers.

McLaws’ case dragged on the longer of the two, but Robertson’s case was just as ugly. On January 21, 1864, Longstreet filed court-martial charges against him for “alleged delinquency and pessimistic remarks during the [Knoxville] campaign.” A military court was never convened to hear the charges; instead, a more subtle punishment was meted out by transferring Robertson to the Trans-Mississippi Department, where he finished out the war commanding reserve forces.

Bragg may have taken some secret delight in Longstreet’s command problems, but that did not improve his own situation. Eventually, after as much damage as possible had been done to the Army of Tennessee, he was replaced by Joe Johnston, whose last assignment prior to taking over the Army of Tennessee had been the poorly organized defense of Vicksburg. Unfortunately, Johnston was no better served by his lieutenants than Bragg had been. His officers during the fight for Atlanta in the summer of 1864 “raised dissension to a kind of art form,” which eventually contributed to his downfall.

Before that happened, however, the second great internal brawl of the Army of Tennessee occurred. A week after Johnston had assumed command, while the army was encamped at Dalton, Gal, Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne tossed a bombshell into the officer corps by proposing that the Confederacy arm its slaves and use them to fill up the depleted ranks of the armies. Other officers had already advised him not to bring up the controversial subject, if not out of consideration for army unity and morale, then out of consideration for his own promising career.

A furious uproar soon spread far beyond the confines of Johnston’s headquarters. General W.H.T. Walker complained to President Davis in a long letter also signed by Generals Alexander Stewart, Carter Stevenson, Patton Anderson and William Bate. Davis tried to put the lid on the entire matter, ordering Johnston to hush up any further discussion of it in the army. This Johnston did, but Bragg and others in Richmond hereafter associated Cleburne’s name with a “traitorous” scheme of abolition, and Cleburne never won corps command, despite a sterling combat record.

The Confederate situation, while not unique in military history, was nonetheless extremely disruptive. Reading through the records, one gets the feeling sometimes that more swords were surrendered to fellow officers during the war than to the enemy.

The quaint practice of surrendering swords at least provided a peaceful method of resolving personal differences. In other instances, Southern officers preferred to use their sidearms on each other rather than surrendering them. This is what happened on September 6, 1863, at Little Rock, Ark., between Generals John S. Marmaduke and Lucius M. Walker. Both commanded cavalry divisions in Arkansas, and Marmaduke impugned the personal courage of Walker, who had already been declared unfit as an officer by no less an authority than Braxton Bragg. A duel resulted in which Walker was mortally wounded. Following his death the next day, Marmaduke was arrested but quickly released because the army could not afford to lose two cavalry commanders while the enemy was active in the vicinity. Furthermore, Marmaduke was a well-liked officer, and popular opinion in the army was clearly on his side.

In April 1865, three days before Lee surrendered, Colonel George W. Baylor shot Brig. Gen. John A. Wharton, the latter being unarmed at the time. Baylor said Wharton called him a liar and slapped his face, sufficient provocation for any red-blooded Southern gentleman, but Wharton’s friends said Baylor was angry about being passed over for promotion and blamed Wharton for holding him back. Baylor was never charged with any crime, and even if he had been, it is doubtful whether other Southern gentlemen, particularly if they were Texans, would have convicted him.

There is no telling how many dueling challenges were issued and never acted upon. After Malvern Hill, General Robert Toombs challenged D.H. Hill to a duel for accusing him of “taking the field too late and leaving it too soon.” While Hill’s unofficial criticism had said nothing about Toombs’ brigade, Toombs interpreted the insult to be aimed at both himself and his brigade, and therefore demanded the “satisfaction usual among gentlemen.”

The two men sparred back and forth in a series of letters, with Hill reminding Toombs that they were prohibited from issuing or accepting challenges to duel “by the plainest principles of duty and the laws which we have mutually sworn to serve.” In the end, Toombs had to be satisfied with publicly calling Hill a “poltroon,” a taunt which no one else took seriously because of Hill’s well-known courage on the battlefield.

Constant squabbling among senior officers, accompanied by bitter recriminations and indiscriminate dismissals and transfers, ate away at the army’s heart and soul. Jefferson Davis himself never understood this fact and incredibly drew the opposite conclusion from his personal experience. After the Revolt of the Generals, he stated with more wishful thinking than common sense, “I have learned that cordial cooperation between officers is not vital to success.”

Noted historian Bell Wiley was closer to the truth when he observed: “Perhaps the most costly of the Confederacy’s shortcomings was the disharmony among its people….One who delves deeply into the literature of the period may easily conclude that Southerners hated each other more than they did the Yankees.”