Two wild aerial battles in the fall of 1951 demonstrated that the days of propeller-driven bombers were numbered.

After the briefing for the 307th Bombardment Group’s October 23, 1951, mission, B-29 navigator 1st Lieutenant Fred Meier jotted in his diary:

“Briefed for MiG Alley mission. Namsi Airfield.” An ominous target, Namsi lay scarcely 30 miles from Antung, where 100 Communist MiG-15 fighters were based.

Less than a year earlier, another B-29 crew attacking a different North Korean air base registered one of the first encounters with the sweptwing jet. The MiG-15 bounced the lone Superfortress, pummeled it, then disappeared. The MiGs outflew American aircraft in Korea until the U.S. Air Force deployed a potent antidote: North American’s sweptwing F-86 Sabre. Still, F-86 squadrons from the 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing faced stubborn, skilled resistance. The MiG pilots, many of them Russians, were as good as their aircraft.

By April 1951, with the ground war stalemated, Sabre-versus-MiG aerial combat centered in MiG Alley, a narrow North Korean air corridor bounded on the north by the Yalu River. Both sides claimed MiG Alley dominance, but the contest was more evenly matched than either admitted. The MiG-15 outclimbed the early-model F-86 and reached higher altitudes. Moreover, Soviet dictator Josef Stalin stocked MiG Alley with two crack fighter divisions, the 303rd and 324th.

But MiG Alley air battles also impacted wider war strategy. Both the F-86 and MiG-15 were point-defense interceptors designed to confront incoming multiengine bombers. Because U.N. forces couldn’t hope to outmatch Chinese manpower, they needed to counter it by bombing supply lines running from China through North Korea. Acclaim showered on America’s first jet aces obscured the fact that F-86 pilots struggled to protect the lumbering B-29s from MiG predators. “They were attacking in groups of four to six aircraft,” recalled 335th Fighter Interceptor Squadron (FIS) leader Major Winton “Bones” Marshall, “which was more than the two-ship [F-86] element could cope with.” In April, when dozens of B-29s shielded by F-86s attacked a Yalu River bridge, three Superforts were shot down and seven more damaged without making a dent in the bridge.

Over the ensuing months, as Korean truce talks commenced, Air Force planners struggled to devise new tactics to overcome the problem. One option was to take out new North Korean airfields. By October 1951, with truce negotiations adjourned, the stage was set for two bomber-fighter MiG Alley showdowns.

Wakeup came at 1 a.m. for the nine B-29 crews of the 307th Bomb Group assigned to the October 23 raid. Takeoffs from Okinawa’s Kadena airfield involved agonizingly slow acceleration that seemed to gobble up the entire runway. After leveling off at 5,000 feet, the airmen settled in to transit the East China Sea.

Crews were a blend of rookies and World War II veteran reservists. Though most of the “retreads” didn’t want to be there, they were mature and experienced, qualities the younger crewmen valued. Captain Clarence “Fog” Fogler, for example, the lead aircraft commander, had survived some of the worst WWII B-24 Liberator missions. On April 12, when Fogler participated in the Yalu bridge fiasco, he somehow got his B-29 Sit ’n Git back unscathed.

Flying at 20,000 feet and aligned in wedge-shaped flights of three aircraft each—Able, Baker and Charlie—the B-29s crossed Korea’s south coast near Kwanju at 7:45 a.m. Danger was still two hours away—the time it took to reach MiG Alley. Expecting low clouds, the crews planned to use SHORAN (short range navigation), an electronic system that enabled bombing without actually seeing the target. SHORAN required flying an electronically prescribed arc all through the bomb run, precluding evasive maneuvers. Because continuous banking risked midair collision, the ships spread out. Without fighter escort, they were sitting ducks.

At 9:35, 55 close-cover Republic F-84 Thunderjets joined up with the B-29s. The F-84s, though welcome, were no match for MiG-15s. Sturdier protection lay with the high cover: two 16-ship Sabre formations taking off a little after 9. The enemy was already intercepting heavy radio traffic and sensed a major air attack—perhaps even against Manchuria. The 303rd Division’s Soviet ground commander scrambled three regiments of 20 MiGs each: one regiment to guard Antung, two to cross the Yalu to confront the B-29s.

The Superforts banked left into the SHORAN path 45 miles east of Namsi. Each pilot had only to keep a needle centered on a calibrated instrument display to stay on course. To guard the slower B-29s, the F-84s flew lazy-eight patterns. Meanwhile, the Sabre formations set up a racetrack pattern above and behind.

SHORAN routed all nine B-29s over radar-controlled anti-aircraft cannons at Taechon. Two ships—Police Action (Baker Lead) and Charlie Lead—were jolted by direct hits. No longer able to follow the SHORAN track, Police Action’s pilot, 1st Lt. Bill Reeter, relinquished the lead. Beyond Taechon, an uneasy calm set in. The B-29s were now four minutes from Namsi—and more flak. MiGs stayed clear of the flak fields, so now was the time to expect them.

At 9:40 the 18th Guards Fighter Regiment approached the Sabre escorts. When its leader, Lt. Col. Aleksandr P. Smorchkov, detected the bombers, he ordered 14 MiGs to tackle the Sabres while he led the remaining six against “the big ones.” Splitting into pairs, Smorchkov’s contingent slashed through the slower, less-nimble F-84s, zoomed to within cannon range of the B-29s, then slammed on speed brakes and opened fire.

Moments later, eight F-86s confronted a second, fast-approaching MiG regiment, the 523rd. As the MiGs broke right to evade, one of the Soviet pilots sighted the Superforts’ silvery wings and fu-

selages standing out against the clouds. “We have big ones below,” he radioed his regiment leader, Major Dmitry P. Oskin, who immediately snapped his MiG into a half roll, diving for the B-29s. “Everyone attack the big ones!” Oskin ordered.

Meanwhile, Smorchkov got 1st Lt. Tom Shields’ B-29 (Charlie Lead) in his sights. Shields tried to maneuver as cannon rounds struck the wings, but his ship failed to respond. “Salvo the bombs!” Shields ordered. “Lower the nose wheel! Get ready for bailout!” But when control momentarily returned, he canceled the bailout. Then came a warning from a gunner: “Right wing and number three engine on fire!” Charlie Lead lurched into a spiraling dive. At 18,000 feet, Shields ordered his crew out.

Aboard Sit ’n Git (Able Lead), navigator Fred Meier sat behind the bombardier on the glassed-in flight deck. At “bombs away,” radio operator Bernie Blumenthal alerted the crew by interphone, “MiGs in the vicinity!” To Meier, the MiGs (most likely piloted by Oskin and his five wingmen) seemed to flash by from everywhere. Left blister gunner Rolland Miller fired at an incoming MiG even as flames erupted from the adjacent B-29 (Able Three), which vanished into the clouds, with two parachute canopies drifting behind.

Radio circuits buzzed against a background of hammering guns, muffled explosions and incoherent shouts.

“Catch that flight of MiGs coming off the bombers!” urged one F-84 pilot.

“Catch them before they get to the bombers!” pleaded another.

“Sorry guys,” an F-86 pilot reportedly replied, “we can’t do it.”

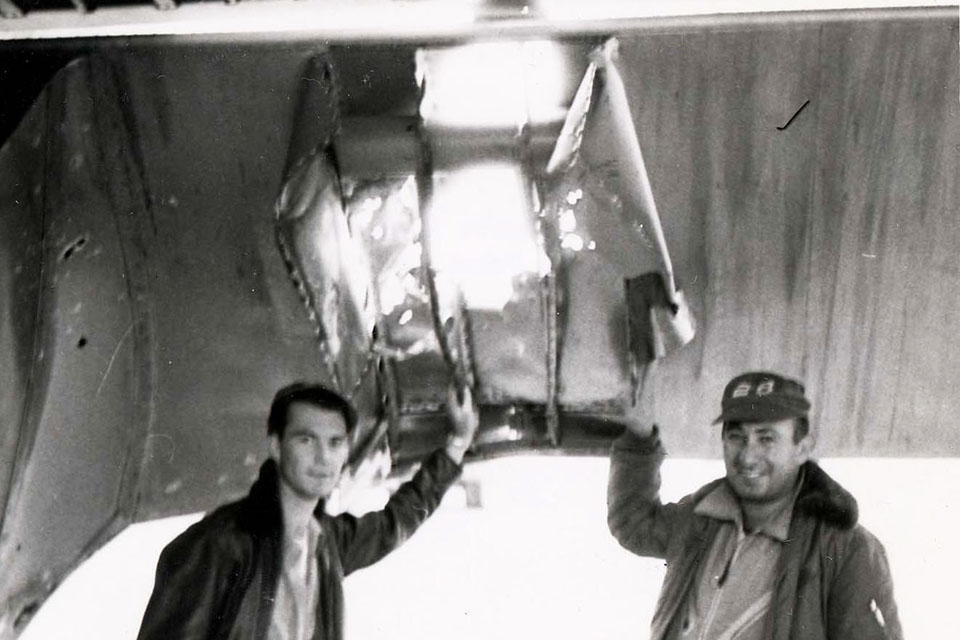

In less than 15 minutes over Namsi, with the additional loss of Baker Two, three B-29s were shot down and three more severely damaged. (The Soviets claimed 10 B-29s downed, one more than actually flew the mission.) Only one Superfort returned directly to Okinawa. Fogler’s Sit ’n Git was one of three making emergency landings at Kimpo. Half the B-29 crewmen were killed or wounded, the highest single air mission casualty tally of the war. The heavy bombers were soon withdrawn from daylight operations. Combined October losses to MiGs rose to 14 aircraft, the highest one-month total of the war.

Exaggerated claims aside, the Communists could be well satisfied. Yet, according to historian Xiaoming Zhang, Chinese leaders were determined to flex their own bomber muscle. A likely target was the island of Taehwa-do (Cho-do to the Koreans), near the mouth of the Yalu River, where the South Koreans had stationed 1,200 troops along with radar and radio monitoring equipment.

On November 6, nine World War II–vintage Tupolev Tu-2 twin-engine light bombers of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) 8th Division took off from Shenyang to strike Taehwa-do. Sixteen Lavochkin La-11 prop fighters and two-dozen MiG-15s from the PLAAF 3rd Division served as escorts. Despite heavy flak, the bombers destroyed island command posts and storage facilities. No American fighters challenged them, and all aircraft returned safely. Flushed with this new success, Chinese planners decided to duplicate the tactic on a follow-up raid.

For its part, the USAF looked to avenge Namsi. So, on the morning of November 30, when U.S. Army intelligence anticipated an imminent assault on Taehwa-do, every 4th Wing F-86 pilot was either airborne or on standby.

Gao Yueming, a five-year flying veteran, led the mission’s nine Tu-2s. Owing to inflight scheduling errors, Gao’s bombers reached their scheduled midafternoon rendezvous fully five minutes ahead of schedule—a fatal mistake. They managed to link up with their 16 Lavochkin escorts, but the 12 3rd Division MiG-15s were only just then leaving Antung.

Gao and his crews then made another blunder: Spotting a distant jet formation, they blithely assumed it was a homeward-bound MiG patrol. Instead, it was 31 F-86s from the 334th, 335th and 336th Fighter Interceptor squadrons, all led by 4th Wing commander Colonel Ben Preston. Leading the 335th FIS contingent was 32-year-old Bones Marshall, by then a six-month MiG Alley veteran credited with four kills. The 334th FIS flight leader was George Davis, also 32 and a Pacific War P-47 Thunderbolt ace. Davis had reached Korea right after the Namsi disaster, but just three days earlier had claimed a double: two MiG kills on the same mission.

Though surprised by the Sabre onslaught, Gao ordered his Tu-2s to press on toward Taehwa-do, two minutes away. In quick succession, however, Gao lost two bombers and two escorts. First Lieutenant Douglas K. Evans of the 336th scored first, sending a Tu-2 trailing fire into the sea. An La-11 escort fell next, blasted by Preston. Almost simultaneously, Marshall swooped in, setting fire to both a Tupolev and a Lavochkin.

Davis and wingman 2nd Lt. Merlyn Hroch entered the fray from well above the Chinese formation. Reversing course and diving from 10,000 feet with Hroch tight on his wing, Davis raked one Tupolev, forcing it to break formation. Davis then turned to jump another, exploding that bomber with fuel tank hits. Breaking again—and this time losing Hroch—he got behind a third Tu-2. Squeezing the trigger, he watched the Tupolev erupt in flames and its crew jump.

Though the Chinese La-11s couldn’t match the F-86s’ speed and climbing ability, they were agile. When Bones Marshall jumped a Lavochkin flown by veteran Wang Tianbao, the Chinese pilot broke hard, forcing him to overshoot. Wang then got in a long deflection shot. One 23mm shell hit the F-86’s left wing, just missing a fuel cell. A second exploded against the cockpit headrest, completely destroying the canopy, lacerating Marshall and briefly knocking him unconscious. Bones came to just in time to recover from a near-fatal spin into the Yellow Sea. He limped his crippled fighter back to Suwon.

Despite Wang’s display of skill, the props proved no match for the jets. Though still bound doggedly for Taehwa-do, all but one Tupolev took hits. Gao watched flames pour from both engines of a Tu-2 as it staggered along for a few minutes before finally exploding. Then four Sabres concentrated on Gao’s wingman, finally detonating his fuel tanks. Fire engulfed the bomber, and no parachutes appeared as it fell.

Finally reaching the target, Gao salvoed his bombs and fled east. The other survivors dropped their bombs seconds later. Most landed on the beach, kicking up sand.

The MiG-15s, meanwhile, arrived too late to help. One MiG punched a big hole in the wing of 1st Lt. Raymond Barton’s F-86. George Davis, then homebound and low on fuel, picked up Barton’s call for help. Turning north, Davis soon spotted two aircraft. Unable to distinguish Sabre from MiG, he instructed Barton to turn first left then right. When the Chinese MiG did neither, Davis pulled in behind it and opened fire. Hits to fuselage, wings and cockpit sent the MiG crashing into the sea.

For the PLAAF, the November 30 Taehwa-do mission was a disaster comparable to that suffered by the Americans at Namsi. Although Sabre pilots claimed eight Tupolevs destroyed, the actual count was four Tu-2s, three La-11s and a MiG-15. Fifteen Chinese bomber crewmen and four escort pilots died. Realizing the perils of inexperience, the PLAAF curtailed offensive bombing operations to concentrate on MiG-15 training.

Two months later, this new thrust would again pit Chinese MiG pilots against George Davis. By then, with 12 confirmed aerial kills (including his Taehwa-do tally), Davis was the highest-scoring American jet fighter ace.

New Jersey–based writer and historian David Sears is the author of Such Men as These: The Story of the Navy Pilots Who Flew the Deadly Skies Over Korea. Further reading: Black Tuesday Over Namsi: B-29s vs. MiGs—The Forgotten Air Battle of the Korean War, 23 October 1951, by Earl J. McGill; Sabres Over MiG Alley: The F-86 and the Battle for Air Superiority in Korea, by Kenneth P. Werrell; and Red Devils Over the Yalu: A Chronicle of Soviet Aerial Operations in the Korean War 1950-53, by Igor Seidov and Stuart Britton.

Ready to build your own F-86 Sabre? Click here!

Showdowns in MiG Alley appeared in the March 2017 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe today!