As Coronavirus-induced shutdowns swept the nation and exposed cracks in many parts of our society, they also exposed another pressing desire—haircuts. Who among us, man, woman, or child, hasn’t looked in the mirror these past few months and internally screamed, “Shave it off. Shave it all off!”

With access to salons and barbershops cut off, the haircut has become a rallying cry for protestors of the stay-at-home orders. So much so that Vox declared salons and barbershops “the battlefield of a great American culture war.”

This author, whose thick hair seems to be growing outwards not downwards during this quarantine, and whose hair follicles seem to be fighting it out for a prized spot on her scalp—gets it. But as someone who did, once upon a time, “shave it all off” I must encourage restraint.

Nevertheless, the human impulse to look good is understandable, for as the oft-attributed quote from Oscar Wilde notes, “the only thing worse than vanity…is the lack of it.”

Like today, the vanity of styled hair has persisted for centuries—with such a desire surviving through the plagues and wars of history.

Presently, like the highly sought after effortless “French-girl hair,” beginning in the sixteenth century, much of Western Europe took their fashion cues from the wig-wearing French King, Louis XIII (1601-1643). And like how all good fashion trends start, the rise of the wig was due to the premature balding of the king.

Prior to Louis XIII, in French society the wearing of wigs was only deigned for those with red hair, those who were balding, and courtesans, writes Georgina Hill in A History of the English Dress from Saxon Period to Present Day.

After Louis XIII resorted to wearing a wig, courtiers were quick to emulate, historian Michael Kwass notes. In Paris alone, the number of wig makers jumped from 200 in 1673 to 835 in 1765.

The use of human hair was naturally the premium, but despite being banned by wig guilds (yes, there were wig guilds), occasionally hair was used from horses and goats for those in the lower echelons of society.

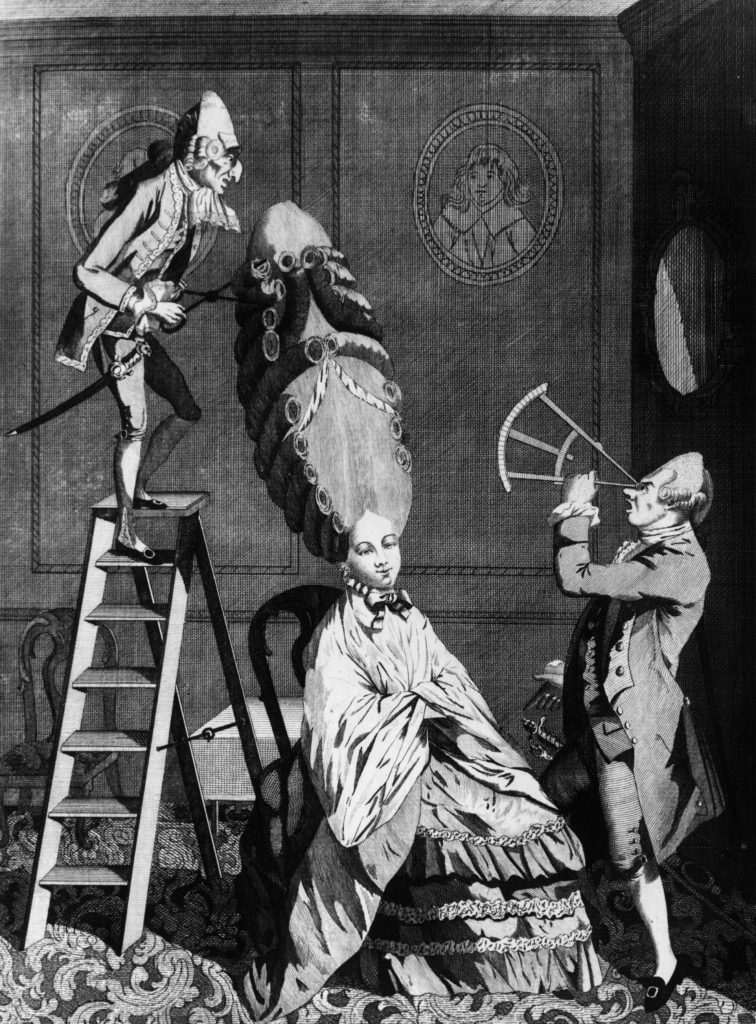

During the reign of Louis XIII’s successor, Louis XIV (1638-1715), full-bottom wigs—characterized by a central part, high side peaks, and long flowing hair down the front and back—were immensely popular among royalty and the nobility. The style itself was so impressively large and dramatic that if often times required up to ten heads of hair for one wig. Louis XIV’s wigmaker Georges Binet even went as far as to declare that he would strip the heads of every French subject in order to cover that of the king.

More than hiding premature balding, the wig soon served several purposes. As towns and cities became increasingly populated during the seventeenth century, so too was the parallel rise of disease and the presence of noxious smells. Bathing regularly still had not caught on, yet the perception of smell and health became increasingly intertwined.

Instead of doing some soul searching that might have led to the conclusion that unwashed wigs, in fact, trapped foul scents in its multi-layered tiers, those within the elite classes in both France and England took pains to conceal foul odors by using scented powders in their wigs. Violet, rose, jasmine, and orange were among the most popular scented powders used by hairdressers.

And while the frequent washing of a wig was absent, rubbing the hair with a napkin to “dry it from its swettiness and filth in the head” was a common element of a barber’s work, writes Emma Markiewicz in her thesis Hair, Wigs and Wig Wearing in Eighteenth-Century England.

Because sure, that’ll do the trick.

Unsurprisingly, the wig itself created its own issues, namely lice. In the Annals of Medicine, for the Year 1796, Andrew Duncan noted that the existence of lice was rife within a wearers wig, coating the hair in “such disgusting numbers.”

Many hairdressers of the time encouraged wig wearers to frequently comb one’s hair to defend against the pernicious louse, but as Markiewicz notes, the complicated and expensive hairstyles sported by many fashionable women during this time meant that wigs were sometimes left untouched for months.

Wigs, however, were also used to disguise something far more sinister—syphilis.

As syphilis spread unabated through Western Europe beginning in the sixteenth century, the powdered wig also became another means of concealment. The initial symptoms of syphilis, among others, include hair loss and bloody head sores. The wig came into play two-fold: firstly, it hid such sores; secondly the scented powder helped to mask the smell of the open ulcers on the head.

However, by the end of the French Revolution, the full-bottom wigs of the Old Regime were deemed frivolous, with a renunciation of the older courtly aesthetic in the name of convenience, writes Kwass. Furthermore, under Napoleon Bonaparte the nation was militarized. It’s hard to march on Russia while wearing a heavy wig, or so I hear.

The British themselves largely stopped donning their powdered wigs in 1795 when William Pitt’s government realized that money could be made by taxing hair powder. At that time, a single hairstyle could use at least a pound of hair powder, and a tax on such was estimated to yield £210,000 a year. England, which had suffered a recent defeat in a war with the Low Countries, saw this tax as a way to maintain its army.

Unlike their American brethren who dumped tea into the Boston harbor to protest taxation, the English didn’t take to the Thames to dump their wigs. However, they weren’t fooled by Pitt’s ploy and slowly the wearing of the powdered wig mercifully went on the wane.

So perhaps as you survey your split ends, be grateful that a towering bouffant of hair, riddled with lice, is no longer in style.