Justices label corporations as ‘citizens,’ making it easier to sue businesses

Forging functional constitutional details for the government they were forming, the Founders gave one issue little discussion: virtually all agreed that when a citizen of one state had a legal dispute with a citizen of another state, the party of the first part should have the option of bringing that case in federal court rather than in a court administered by the defendant’s home state. “It may happen that a strong prejudice may arise in some states against the citizens of another,” James Madison suggested in advocating for what came to be called “diversity jurisdiction.” The concept had to do with optics. Even if a litigant from out of state got a fair hearing, Madison said, “at all events, he might think himself injured.”

Opening federal courts to cases involving citizens of different states made sense when John Doe was suing Richard Roe. However, what if one party was not an individual but a corporation, or if both parties fit that description? The idea that for legal purposes a corporation can be a “person,” which dates to Roman times, figured in the English judicial traditions that underpin American law. But it was unclear whether a “person” was also a “citizen.”

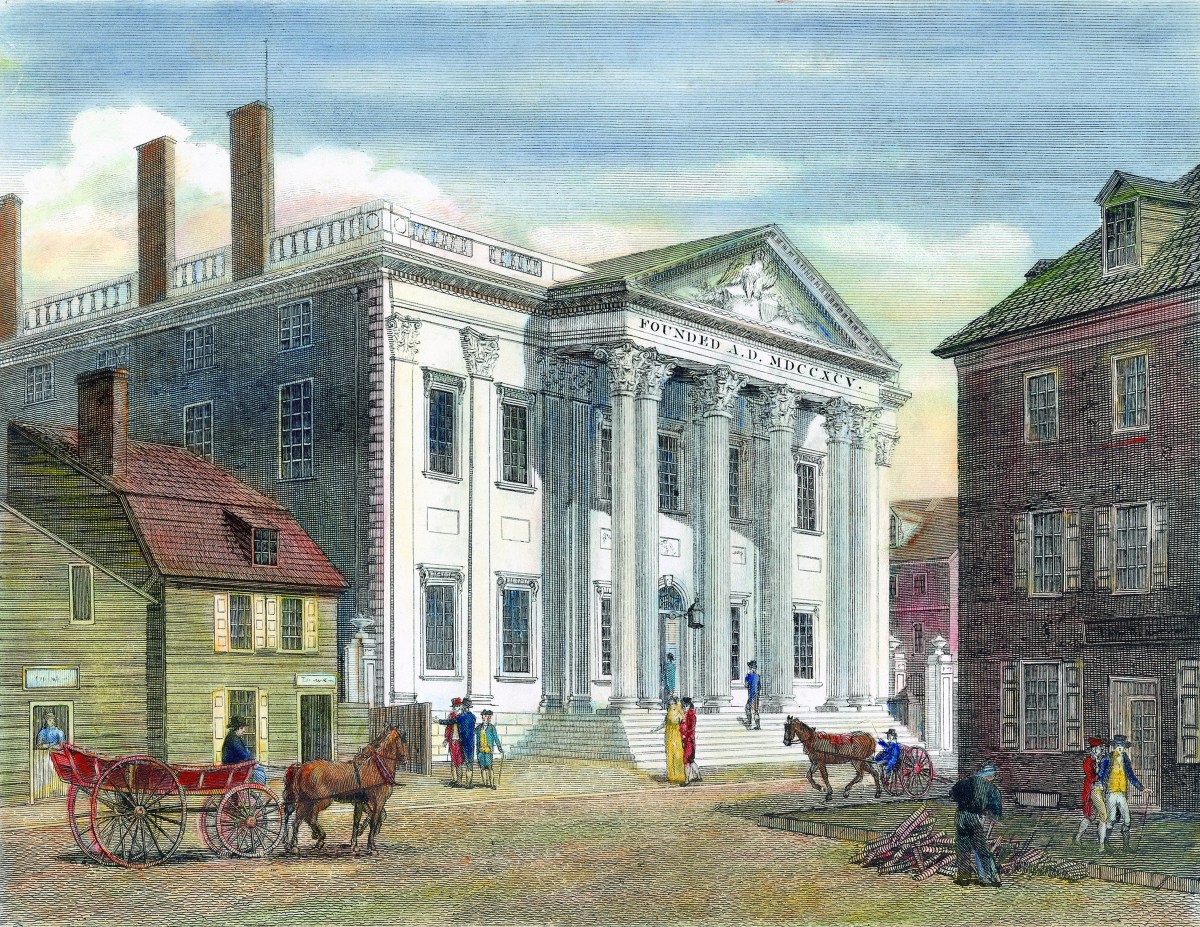

In 1809, just 21 years after the Constitution was ratified, the Supreme Court faced the question, unequivocally declaring that the diversity jurisdiction clause did not cover corporations. The ruling came when Georgia levied a tax on a congressionally chartered bank. When the bank balked, state revenue officers forced their way into that establishment’s Savannah branch and carted off two boxes containing $2,004 in silver.

The bank, asserting it had Pennsylvania citizenship, went to federal court demanding that Georgia return the bullion. Chief Justice John Marshall explained in Bank of the United States v. Deveaux that the aggrieved bank could not use the federal courts because “that invisible, intangible, and artificial being, that mere legal entity, a corporation aggregate, is certainly not a citizen; and consequently cannot sue or be sued in the courts of the United States.”

Bank of the United States was a clear holding, but not, in 1809, a very important one. Few businesses then organized themselves as corporations, in part because to organize as a corporation an enterprise needed a special charter issued by a state legislature. For the next 30 years, plaintiffs challenging this principle were rebuffed by a High Court convinced a corporation was not a citizen, even as the Industrial Revolution was creating a need for bigger enterprises and changing the way that businesses organized. By 1840 states had passed general incorporation laws, allowing any business to organize as a corporation by filing the proper documents. Even in 1840, nonetheless, in a case three Louisianans brought against a Mississippi bank, the justices found that precedent forced them to deny diversity jurisdiction, in the process explicitly stating their reluctance to do so.

The time clearly had come for the High Court to reexamine Bank of the United States. An opportunity came four years later. The matter revolved around a railroad now a footnote in American history but then a lofty entrepreneurial dream. The Louisville, Cincinnati & Charleston Railroad had incorporated in South Carolina in 1835. The corporation was to build a 700-mile line between Charleston and Cincinnati—the first rail link connecting Southern cotton plantations and Midwestern farms to Eastern Seaboard markets. The plan fell apart when the railroad had trouble getting permits from certain states and reverberations from the Panic of 1837 torpedoed the national economy. Contractor Thomas W. Letson sued to get the sum the rail line owed him for preparing a bed for a 48-mile segment between Orangeburg and Columbia, South Carolina. As a citizen of New York, Letson, invoking the diversity provision, sued in federal court, which awarded him $18,142.23.

Louisville Railroad appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing in Louisville Railroad v. Letson that under Bank of the United States v. Deveaux Letson could not claim diversity jurisdiction. The rail line was not a citizen of South Carolina, the corporation’s lawyers asserted, but merely an agglomeration of shareholders whose ranks included citizens of New York. Thus, the case involved New Yorkers suing New Yorkers and so lacked the disparate citizenship the Constitution requires, the attorneys claimed.

The justices weren’t buying it. They unanimously held Letson and the railroad to be citizens of different states, meaning that the federal trial court had been right to take the case and that the court’s award to the contractor was valid. The High Court ruling “completely changed the status of corporations for purposes of jurisdiction of the federal courts,” William Overton Harris wrote in the Virginia Law Review.

This watershed decision was the work of a tremendously shrunken court. Justice Smith Thompson recently had died. Three members—including Chief Justice Roger Taney—had recused themselves, probably because they owned railroad stock. Justice James Moore Wayne, who was to serve on the court a total of 32 years, in his day longer than any justices except Marshall and Joseph Story, wrote the decision. Wayne acknowledged in his exegesis that by 1844 there existed a persuasive collection of cases holding that a corporation was not a citizen.

However, Wayne said, the justices’ duty lay in “yielding to decided cases everything that can be claimed for them on the score of authority except the surrender of conscience.” Their consciences told them that in reality a corporation created by state charter in legal proceedings “seems to be a person, though an artificial one, inhabiting and belonging to that state, and therefore entitled, for the purposes of suing and being sued, to be deemed a citizen of that state.” Wayne insisted that in opening federal courts’ doors to a wide variety of business cases the justices were not establishing any new reading of the law, but merely adhering to “the true principles of interpretation of the Constitution.”

The ensuing decision was, as White House associate counsel Tara Helfman wrote in a recent law journal article, “transformative.” Federal courts became the arena of choice for commercial litigation involving significant sums—Congress now sets $75,000 as the minimum amount which must be in dispute to trigger diversity jurisdiction—and was a major factor in federal trial courts’ blossoming importance.

Plaintiff Letson himself was one of the first to benefit: the year after the Louisville Railroad decision, the federal court in Baltimore ordered the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Company to pay Letson $1.5 million due when the company disavowed a contract awarded his firm to complete that waterway (“Watery Waymaking,” December 2019).

At first the primary users of the new power to put corporate disputes into federal courts were plaintiffs suing businesses, but within 20 years corporations had begun invoking diversity jurisdiction to get disputes into federal courts. The goal was to make their arguments before judges more attuned to hearing complex legal arguments and, often, at locations so distant as to disadvantage defendants. That shift swelled the federal court workload. In 1844 only six states were home to more than one U.S. District Court; over the next two decades, thanks in good part to the volume of business cases unleashed by Louisville Railroad, the federal judicial system added trial courts in eight states.

This SCOTUS 101 column appeared in the December 2020 issue of American History.