Around 5:15 on Saturday evening, May 14, 1892, Johnny Boyce crested the grade on Middle Creek Road above the Sacramento River in the heart of northern California, en route to Redding. He’d just started downhill when out stepped a figure on the riverbank, wearing a red calico mask and drawing a bead on him with a double-barreled shotgun, both hammers cocked. As a stagecoach driver, Boyce was used to holdups. In fact, he’d been robbed four days earlier by a bandit who looked suspiciously similar to the man before him. But highwaymen generally operated farther from civilization, not within 5 miles of a town the size of Redding. Rather than risk being shot, Boyce reined the four-horse team that was pulling the Redding and Weaverville Stage Line coach to a stop.

“Passenger, throw up your hands!” the masked man ordered lone passenger George Suhr, sitting to the left of Boyce on the driver’s seat.

“Throw down the gold box,” the highwayman told Boyce.

The driver hopped to it, tossing down the smaller of two Wells, Fargo & Co. strongboxes, then hefting the larger, 100-pound box over the side, which bounced off a coach wheel before landing at the robber’s feet. But Wells, Fargo shotgun messenger Amos Buchanan “Buck” Montgomery, watching from inside the coach, had no intention of letting someone ride off with the treasure he’d sworn to protect. Standing over 6 feet tall, tipping the scales at 200 pounds and known as a crack shot, Montgomery had sent several highwaymen to San Quentin State Prison. This one he planned to send to hell.

Raising his scattergun, Montgomery aimed and fired. The blast caught the masked robber in the torso and face, dropping him to his knees. Instinctively, the highwayman triggered his shotgun. Although only one of the barrels fired, buckshot riddled both of Boyce’s thighs, while three slugs struck Suhr just below the knee. At almost the same moment a partner in crime emerged from hiding in the brush a little behind the stagecoach. Armed with a Colt .44 revolver, he fired at Montgomery, hitting the shotgun messenger twice in the back—one bullet boring clean through his body, the other lodging in his hip. As Montgomery crumpled, both robbers disappeared into the brush.

Panicked by the gunfire, the team of horses drawing the stage bolted about a quarter mile down the road before Boyce managed to rein them in. Fearing the worst, the driver called down to Montgomery, asking if he’d been shot.

“Great God, yes,” the shotgun messenger called back, “and I am shot to die!”

(California Digital Newspaper Collection)

Boyce resolved to get Montgomery to a doctor as soon as possible. As Boyce couldn’t work the foot brake in his condition, and Suhr couldn’t drive the four-horse team, driver and passenger swapped places. Boyce slumped down into the boot to work the reins while Suhr pumped the brake. As chance would have it, a mile down the road they met Dr. Benjamin E. Stevenson and wife Mary, in a northbound buggy drawn by a double team of bays. While the doctor tended Montgomery and Boyce, Mary Stevenson drove furiously back to Redding, reaching town within a half hour, the four bays panting and foaming with the exertion. Outside the post office she related to gathering townspeople that the stage had been held up and men injured. While California National Guard Major T.W.H. “Tall Sycamore” Shanahan mustered 20 members of his Company E as a posse, Mary located local Dr. Olin J. Lawry at his residence, bade him enter the buggy and drove back up Middle Creek Road at a gallop.

Meanwhile, Dr. Stevenson had not been idle. Directing Suhr to enter the coach and provide Montgomery what little comfort he could, the doctor climbed up into the driver’s seat and took the reins from Boyce. Two miles down the road the stage carrying Dr. Stevenson, Boyce, Suhr and Montgomery reached the hotel at Middle Cut stage station. They were soon joined by Mary Stevenson, Dr. Lawry, Montgomery’s pregnant wife, Jennie, and their two young sons. Sadly, the shotgun messenger’s wounds were beyond any doctor’s power, and shortly after 7 p.m. Buck breathed his last. He was 35 years old.

By the time Shanahan and posse reached the scene of the crime, it was near dusk, and the guardsmen wanted blood—a dangerous combination. Spotting two shadowy figures lurking in the roadside brush, Shanahan demanded their surrender, waited two minutes, then ordered his men to open fire. When the pair bolted, the major himself shot at the suspects with his Winchester. He managed to hit one of the pair and capture both. Only, the two men weren’t the highwaymen but fellow soldiers. Having wounded guardsman George Holseworth in the shoulder, and with storm clouds moving in, the company returned to Redding.

Constable Charles Behrns, responding from Shasta, showed more grit.

Off the roadside, downslope from the scene of the robbery, Constable Behrns located the strongboxes. Broken open and emptied, they had held $3,375 in gold, most of that in bullion from the Weaverville and Brown Bear mines. Near them Behrns found two discarded red calico handkerchiefs cut with eyeholes. One was bloodstained and bore several buckshot holes. The constable tracked the fugitives’ blood trail for nearly a mile before darkness fell and the storm burst, washing away the markings. Behrns then returned to Shasta and wired his findings to Undersheriff Sylvester Hull in Redding. Based on the amount of blood spilled, the constable expressed confidence the wounded highwayman would soon be a corpse.

With Redding in an uproar about the robbery and murder, Undersheriff Hull had little trouble raising a citizens posse the next morning. Word spread quickly, and around 2 p.m. three teenagers from nearby Shasta—Harry Paige, Lloyd Carter and Nick Cusick—following a ditch about a half mile southwest of the robbery, spied a badly wounded man struggling to climb a steep slope. Gamely, they called for his surrender, and the bandit obliged. The teens turned the man over to Constable Behrns, who again wired Hull. The undersheriff soon arrived to transport the prisoner to Redding.

(Courtesy of the Shasta Historical Society.)

A few minutes after 6 p.m. Hull deposited his prisoner on a cot in a cell of the Shasta County Courthouse in Redding. The highwayman, who gave his name as Lee Howard and his age as 22 years old, had suffered 11 buckshot wounds: four in his left breast and one each to his right breastbone, his right side below the elbow, his right forearm, the back of his right hand, the outer corner of his right eye, on the bridge of his nose and to his upper lip. Posse members had recovered his own cheap muzzle-loading shotgun, only one barrel of which was functional. While readily admitting to having robbed the stage, he refused to give up the name of his partner.

While Hull encouraged his prisoner to talk, he didn’t believe much of what was said. For one, the undersheriff was certain Lee Howard was an alias. The next day his suspicions were corroborated by veteran Wells, Fargo & Co. detectives James B. Hume and John N. Thacker, who between them had an encyclopedic knowledge of California criminals. Within a week the detectives identified the prisoner as Charlie Ruggles, whose partner was almost certainly brother John, about 10 years Charlie’s senior. The elder Ruggles brother had served a stretch in the penitentiary for having held up a man in San Joaquin. He’d since bought farmland south of Fresno, but the detectives soon dug up a witness who’d seen John leading horses from a pasture outside Redding a couple weeks before the robbery.

While Charlie Ruggles languished in a cell in Redding, the search continued for John Ruggles, justly considered armed and dangerous.

As later revealed in a confessional letter he’d written on the event of his death, John had indeed fatally shot Montgomery. After the team bolted with the stagecoach, he’d run downhill for an ax he’d left in the roadside gulch. A wounded Charlie followed close behind, carrying his shotgun with his uninjured left hand. John could see his younger brother was in bad shape. As Charlie clawed the calico mask from his bloody face, he pointed back up toward the strongboxes, mumbled, “Go,” and said he was “done for.”

John rushed back upslope to the road to grab the loot. As he lugged the strongboxes downhill to Charlie, John watched as his younger brother reeled, dropped the shotgun, stumbled and rolled face-first into shallow Middle Creek. Rushing to Charlie’s side, John lifted his brother from the water and rolled him onto his back.

“Oh, what an awful sight,” John recalled in the letter, “his head literally shot full of holes, and the blood just running all over his clothes and making puddles around him.”

When John asked if there was anything he could do, Charlie pointed to the creek and said, “Water.” John paused to give his brother a drink and clean the blood from his face before using the ax to break open the strongboxes. Inside were coins and a fortune in gold dust, which the elder Ruggles scooped into a large flour sack. John realized that Charlie, his “lifeblood running from a dozen holes in his poor frame,” stood little chance of surviving his wounds. Selfishly, he saw a silver lining in his brother’s condition.

I must take all my evidence in his pockets away, John told himself, and as the holes in his face will swell, he will never be recognized, and I will go back to Tulare and keep my secret and say he has gone to Montana.

Methodically combing through Charlie’s pockets, John removed all personal possessions save for a small knife, adding them to the flour sack. The shotgun he tossed beneath a bush. John then shook his brother’s good hand farewell. “Goodbye, darling brother Charles,” he said. “I’ll have an awful revenge for this.” Then, with the bulging sack slung over his left shoulder and his right hand clutching a cocked .44, John headed west into the hills.

When the downpour struck, John lost his way. Around 3:40 in the morning he emerged on private property in Shasta, a few miles west of the robbery site. There he sought shelter in a washout made by the high-pressure pumps and nozzles of a hydraulic mining operation. Problem was, something else had had the same idea—“a good-sized bear,” John recalled. “He was about 8 feet long and perhaps weighed 500 pounds. I dropped the gold in the sack, kerplunk, on the ground and drew my other .44 with my left hand. The bear had not seen me and had run 30 feet from his nest [sic] and stopped…looking to the left and right, but not behind him, where I was standing with both guns dead in line on him.”

Not so John, who used a table leg to bludgeon to the floor the first vigilante to enter his cell. (Courtesy of the Sahsta Historical Society)

Quietly, John holstered the gun in his left hand, retrieved his loot and crept away. Back in the hills he stumbled across a trail. Fortunately for him, he also spotted two bearded men, armed with shotguns, standing not 60 yards from the trail. He had no doubt they were watching for him.

By then John was tired of running. Over the past 12 hours he’d robbed a stagecoach, killed a man, left his brother for dead, hiked through a rainstorm and narrowly avoided a bear attack. Two men with shotguns weren’t about to scare him off. Balancing the sack across his shoulders, John drew both guns and strode down the trail directly toward the pair. Perhaps recognizing their shotguns would be little match against his .44s, the armed men slunk off.

John Ruggles wouldn’t reappear for more than a month.

On the evening of Sunday, June 19, Deputy Sheriff David H. Wyckoff of Yolo County

—150 miles south of Redding—got a tip that someone matching John Ruggles’ description had been spotted in Woodland, the county seat. The fugitive had stopped by the home of his uncle, T.J. Dexter, on the corner of Second Street and Oak Avenue, then moved on after learning Dexter was away. Wyckoff, who had gone to school with Ruggles, immediately went to the Dexter home, staking it out till nearly 9 p.m. before returning to the office and informing Sheriff N.M. Weaver the stagecoach robber was likely in town.

The sheriff and his deputy received another break when local policemen A.S. Armstrong and L.G. Rhodes reported having spotted the fugitive at the Opera restaurant, a quarter mile north of the Dexter home. Rallying the lawmen, Weaver resolved to capture Ruggles. Wyckoff would take point.

As the deputy sheriff strode into the Opera, he spotted his quarry eating supper at a table near the back of the restaurant. Taking a seat not 6 feet away, Wyckoff ordered coffee. Ruggles raised a newspaper to block his face, but Wyckoff wasn’t fooled. Standing, he drew his pistol and confronted the fugitive. “John, I know you,” Wyckoff said. “Surrender!”

Another man might have, but not John Ruggles. The fugitive stood and had one of his .44s halfway out of the holster before Wyckoff squeezed off a shot, hitting John in the neck. As Wyckoff grappled for Ruggles’ revolver, Weaver, Armstrong and Rhodes stormed through the door and quickly overpowered the fugitive. After having doctors examine their prisoner and dress his wound, the officers placed Ruggles in the county jail. From his money belt they retrieved several hundred dollars in coin, indicating he had hidden the gold dust. They also found the confessional letter in which John had foolishly detailed the stagecoach robbery and gloated over the murder of Montgomery.

“Montgomery’s soul, if he had any, is in hell, and I put him there and am glad of it,” Ruggles had written. “I am glad he suffered—hope he suffered the pangs of eternal hell.”

Seeing to it the letter was published in its entirety in the next day’s edition of the Woodland Daily Democrat, which wired the details to newspapers statewide, the officers must have thought they’d cemented the prosecution’s case. Surely, no jury would sympathize with such a blackhearted villain. They couldn’t have been more wrong.

Days after his arrest John Ruggles was transported to Redding and reunited with brother Charlie. They immediately began planning their defense. While they faced jail time for the robbery, they would almost certainly hang for Montgomery’s murder. Thus, they sought to paint the slain shotgun messenger as a villain rather than a martyr, claiming Buck had in fact set up the robbery.

While the sensational allegation infuriated much of the populace, several local women sympathized with the wounded brothers and seemingly found the dangerous duo scintillatingly attractive. Though the Ruggles boys were manifestly guilty of highway robbery, the women argued, John had been justified in shooting Montgomery because the latter had shot poor little brother Charlie. Outraged by the affections such women heaped on the emboldened rogues, Redding’s leading men were unable to keep the embarrassing development from the headlines.

By mid-July newspapers were decrying the undue attention shown the Ruggles brothers. “Look at the part of which certain fool women of Redding and vicinity are playing,” the Stockton Evening Mail opined. “These women, forgetful of self-respect in the plenitude of their drooling idiocy, are making heroes of the red-handed murderers. They are burying them in flowers and feeding them with cake.”

That an atmosphere of hybristophilia (sexual interest in a criminal—or in this case two criminals) had swept Shasta County was simply too much for its red-blooded men to bear. They remained certain the Ruggles brothers would be judged guilty, but in the meantime their women were making fools of themselves and fellow citizens. It was time to put a stop to their humiliation. It was time for “Judge Lynch.”

Around 1 o’clock in the morning on Sunday, July 24, jailer George Albro was asleep on the third floor of the Shasta County Courthouse when a noise roused him. He woke to the sight of armed masked men carrying torches.

“I thought at first the 10 men were a gang coming to release the Ruggles brothers,” Albro recalled. “They asked me where the keys were, and I told them in the safe.” But the jailer didn’t have the combination.

Using drills, black powder and sledgehammers, the masked men made short work of the safe. On retrieving the keys, members of the mob ordered Albro to take them to the Ruggles boys. As the group passed the cell of a Whiskeytown man imprisoned for having beaten his wife, Albro gestured through the bars for the man to hide. The jailer opened Charlie’s cell first, the young man surrendering without a struggle. Not so John. As Albro opened the door to his cell, the elder brother rushed the first man to enter, bludgeoning him to the floor with a table leg he’d somehow managed to secure. Crowding into the cell, the rest of the vigilantes quickly overwhelmed John.

“Gentlemen, be lenient with my brother,” John pleaded. “He is innocent of this crime.”

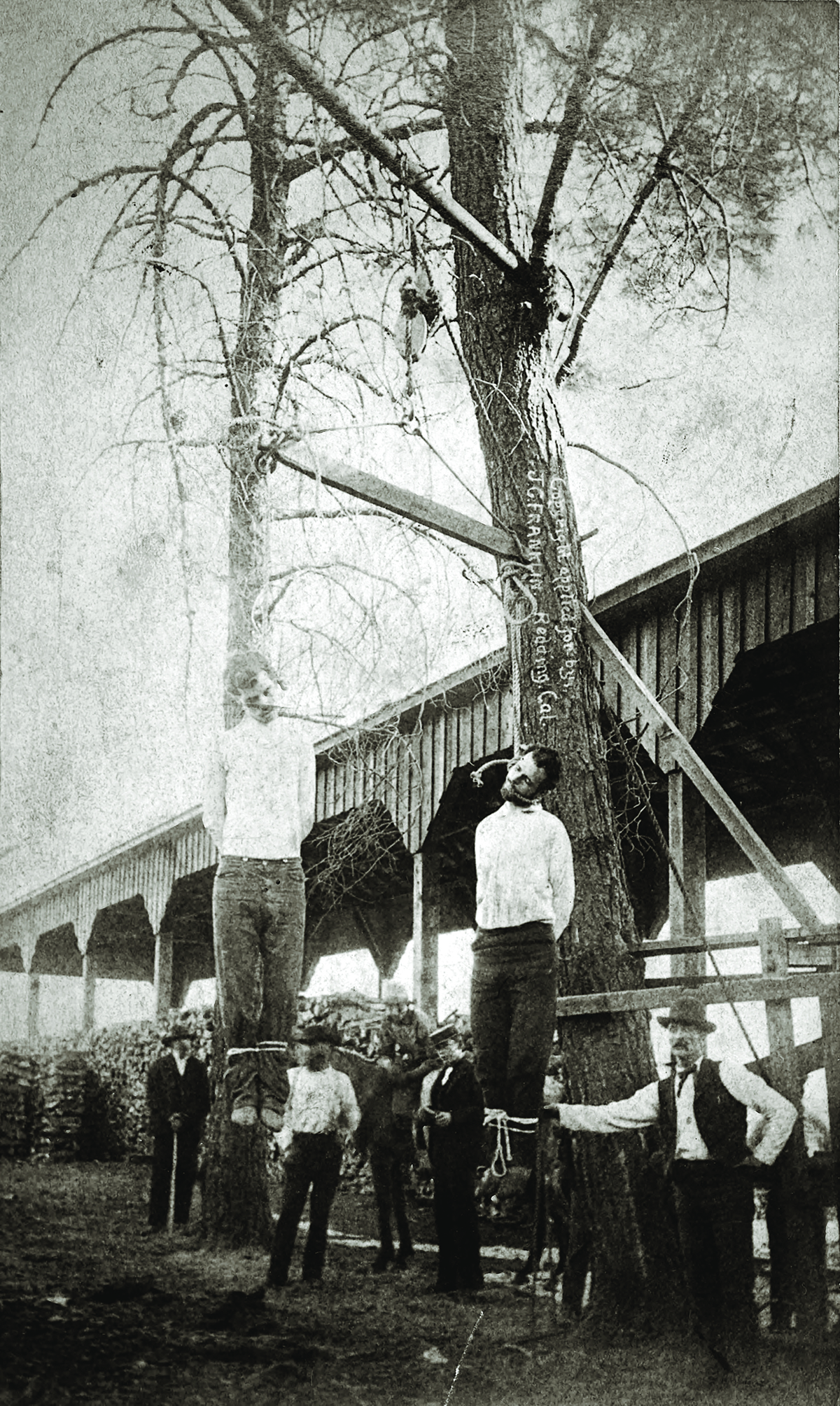

His plea fell on deaf ears. After locking Albro in the sheriff’s office, the mob led John and Charlie from the courthouse. Waiting in the street were some 30 other men. The vigilantes marched the Ruggles boys east through an alley, then a couple more blocks to Etter’s blacksmith shop, near the train tracks, where they’d suspended a crossbeam between two pine trees with block and tackle. Working with grim purpose, the vigilantes fitted nooses around the brothers’ necks, bound their legs together, tied their hands behind their backs and secured the rope ends to iron rings on either end of the crossbeam.

Asked where he’d hidden the money, John replied, “Spare Charlie, and I will tell you.”

“Never mind the treasure,” one impatient man responded. “Tell us if you want to. If not, say what you want to say quick.”

John had nothing more to say. To ensure he wouldn’t cry out, the mob fastened a rope gag in his mouth. On a signal from the vigilante leader, someone cranked a windlass, tensioning the rope leading up and over the block to the crossbeam and hoisting the Ruggles brothers 4 feet off the ground. There John and Charlie, swinging within a handshake’s reach of one another, slowly strangled to death. The bodies hung there until 9 in the morning, when county coroner H.L. Moody had them cut down.

Having little sympathy for the dead highwaymen, and seeing no profit in revealing the identities of the lynch mob, lawmen never mounted an investigation. Doubtless several damsels of Shasta County shed soft tears over the late Ruggles brothers.

The next day Buck Montgomery’s brother Thomas, who lived 100 miles south in Ukiah, heard about the hangings. “Were they to lynch the Ruggles [sic] a hundred times,” he lamented, “it would not return to us our brother.” True, but to Judge Lynch, who had superseded the courts while meting out punishment frontier style, the scales of justice had been balanced.

Matthew Bernstein teaches at Matrix for Success Academy and Los Angeles City College and is the author

of George Hearst: Silver King of the Gilded Age. For further reading he recommends Stagecoach Robberies in California: A Complete Record: 1856–1913, by R. Michael Wilson; Shotguns and Stagecoaches: The Brave Men Who Rode for Wells Fargo in the Wild West, by John Boessenecker; and “The Struggles of the Ruggles,” by Harold L. Edwards, in the August 1995 Wild West.

LOST TREASURE

Although no one dug into the identities of those who lynched stage robbers John and Charlie Ruggles, the search for the stolen gold bullion is another matter. Treasure hunters continue to comb the countryside for the Ruggles boys’ cache, hoping—like John and Charlie—to strike it rich. Meanwhile, in 2015 the Bureau of Land Management unveiled a historical plaque on Shasta County’s Middle Creek Trail to mark the spot of the fatal robbery.

this article first appeared in wild west magazine

Facebook @WildWestMagazine | Twitter @WildWestMag