Staff Sgt. Roy Benavidez had sustained 37 wounds from small-arms fire, grenade shrapnel, bayonet thrusts and a rifle butt to the head. His eyes were pasted shut by dried blood, and he was too weak to move and unable to speak. But he had enough wits about him to sense when medics placed him in a body bag. As a doctor leaned down to check for a pulse, Benavidez did the only thing he could—he spat at the doctor.

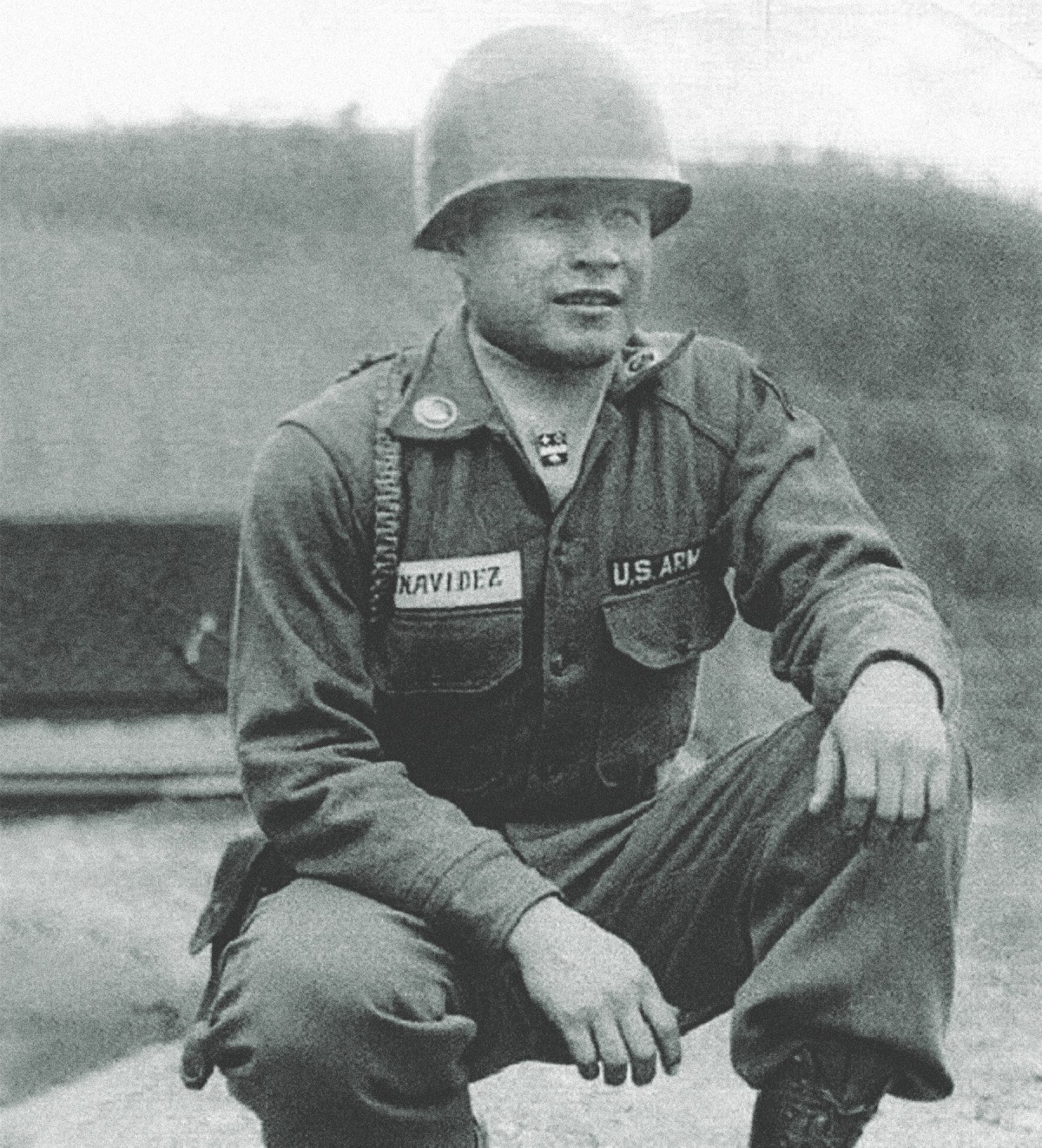

A Texan of Mexican and Yaqui Indian parentage, Benavidez enlisted in the Texas Army National Guard at age 17 in 1952, later switching to active duty in the U.S. Army. In 1959 he completed parachute training and was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division. He later joined the Army Special Forces. On being sent to Vietnam in 1965, he was severely wounded by a land mine. But by 1968 Staff Sgt. Benavidez had recovered and was back in Vietnam.

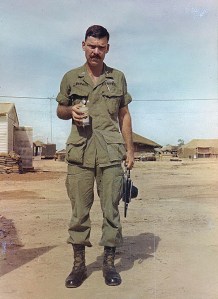

On May 2 of that year at Loc Ninh he overheard a radio call from a 12-man Special Forces patrol under enemy fire that needed immediate extraction. Three helicopters had responded but were unable to land due to the heavy fire. They returned to Loc Ninh with their wounded before making another attempt. Benavidez jumped aboard one of the aircraft. “It was an instant reaction,” he recalled.

At the scene Benavidez directed the helicopter to a clearing, then jumped out and ran 80 yards through what his Medal of Honor citation described as “withering small arms fire” to the trapped men, in the process suffering wounds to his right leg, face and head. Working through his pain, he positioned those team members still able to fight to cover the landing zone and threw smoke canisters to direct the aircrews. Benavidez then carried or dragged half the team members to a responding helicopter and ran alongside, providing covering fire, as it hovered in closer to collect the others. As he struggled to recover the body of team leader Sgt. 1st Class Leroy Wright and the classified documents on his person, the enemy fire intensified, and Benavidez took an enemy round to his abdomen and grenade shrapnel to his back.

At the same moment enemy fire killed the pilot of the helicopter, which crashed. Though bleeding heavily and losing strength, Benavidez secured the documents and made his way to the wreckage to aid the wounded and organize the able-bodied into a defensive perimeter. All the while he kept on his feet, distributing water and ammunition to the men and, his citation notes, “re-instilling in them a will to live and fight.” Benavidez then called in tactical air strikes and directed the fire of supporting gunships to clear the path for another rescue attempt. While aiding one of the wounded, he took another enemy round to the thigh.

When a second helicopter landed, Benavidez helped a wounded man aboard. As he returned for the others, an enemy soldier clubbed him in the mouth with a rifle butt, then lunged at him with a bayonet. Benavidez grabbed the blade, sustaining deep cuts, and killed his attacker with a knife. He then picked up a discarded AK-47 and shot two more enemy soldiers approaching the helicopter. With his little remaining strength Benavidez made a final sweep to bring in the wounded and ensure all classified material had been secured. He then collapsed into the helicopter.

When the startled doctor at the field hospital realized Benavidez was alive, thanks to the sergeant’s well-aimed spit, he sent the wounded man to a rear area hospital. It took more than a year for Benavidez to recover. He had saved at least eight lives and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and four additional Purple Hearts.

In 1981 Benavidez’s DSC was upgraded to the Medal of Honor. That February 24 President Ronald Reagan presented the intrepid sergeant his hard-earned award. MH