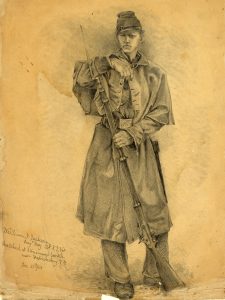

Photography has made great strides since the 19th century, but Robb Kendrick, a photographer who lives near Austin, Texas, is still drawn to tintypes. Kendrick—who also shoots in digital format and 35mm and large-format film—has photographed contemporary working cowboys since the 1980s. His 2008 book Still: Cowboys at the Start of the Twenty-First Century features 148 tintype portraits with an Old West look but taken since the turn of this century.

In the 19th century the tintype process was a relatively inexpensive way to have one’s photograph taken. The best-known tintype from the era is one of Billy the Kid, snapped around 1880 in Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory. The Kid probably paid the unknown itinerant photographer $1 for four small tintype plates. In 2011 the one known surviving plate sold at auction for $2.3 million.

‘In 150 years they’re going to look back and think that you and I had a rough time’

A wet-plate process, tintype photography is demanding. “All images are made and processed at the time you’re shooting the pictures,” Kendrick explains. “You have to coat the metal plate, soak it in silver nitrate. You have about eight or 10 minutes to go out, put it in the camera, shoot the picture, come back and process it. Everything has to be done wet. You have to have a portable darkroom and travel with all the chemicals. It’s like you’re building a house from the foundation up in one sitting, as opposed to working with an architect and working with plans. You’re building it as you go.”

That cumbersome process is something cowboys can appreciate. “Cowboys have a pretty physical job,” Kendrick says, “and they don’t have the highest regard for photographers who come in shooting 35mm like machine guns. A lot have told me, ‘That photography stuff looks pretty easy.’ But then they see the tintype and see how difficult it is. Exposure has to be exact. You can’t miss hardly at all. They look at all this and go, ‘Wow, I can relate to what you’re doing, because that’s not the easiest way to do it, and the results are great.’ It is an interesting relationship.”

Exposures range from four to eight seconds to as long as 10 minutes, one reason people sitting for 19th century tintypes seldom cracked a smile. “Technically, people can’t hold a smile for eight seconds,” says Kendrick. “So if you have a family photo, and the kid is blurred, and the dad looks pissed off, he’s pissed off because the kid moved, and now he has to pay the photographer more money to shoot another picture.”

Born in the Texas Panhandle town of Spur, Kendrick, 52, first discovered photography as a teen. Family members worked some of the big spreads, including the historic 6666 Ranch, and while Kendrick was at East Texas State University (since renamed Texas A&M University–Commerce), he visited the ranches to photograph cowboys. Hooked on the craft after an internship at National Geographic, he has handled various assignments and commissions ever since.

While his medium of choice varies from assignment to assignment, the tintype process holds a particular appeal, Kendrick explains, “because it produces a unique image.” It certainly fits with cowboys. “It also works pretty well with contemporary images,” says the photographer. “Where you have really slick, high-tech architecture, the primitive nature of the tintype makes an interesting contrast.” He has also used the process to photograph mummies in Mexico and rock bands for album covers. “Somebody wanted me to shoot chefs in tintypes, but I had no interest,” Kendrick says. “Then it just becomes a bit of a gimmick.”

Much of what Kendrick photographs has “a people element.” Living with his wife and two teenage sons, he enjoys meeting people who live the rural lifestyle. “I just love spending time around people who love what they do and don’t make a lot of money, because they care more about other things. That’s great.”

How about those unsmiling people in period tintypes? “1870 was a lot more comfortable than 1770,” he says. “In 150 years they’re going to look back and think that you and I had a rough time.” WW

Originally published in the June 2015 issue of Wild West. To see more browse Robb Kendrick’s website.