“Rommel, you magnificent bastard! I read your book!” shouts a triumphant U.S. Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr. (as played by Best Actor Oscar winner, George C. Scott in 1970’s Best Picture, Patton) while watching the March-April 1943 Battle of El Guettar in Tunisia, North Africa. This “gotcha!” exclamation implies the American general gained the key to victory over the German-Italian Axis forces he mistakenly thought were then commanded by Rommel from reading Rommel’s own impressive account of his development as a daring, tactically-innovative troop commander fighting French, Romanian, Russian and Italian units in World War I.

An avid reader of all things military history—his extensive, personally-annotated military history library was donated to the West Point Library—the real Patton probably did read Infanterie greift an, published by then-Lt. Col. Erwin Rommel in Germany in 1937, two years before World War II began and four years before Rommel earned his nickname, “The Desert Fox”. But the first English language edition—heavily abridged and edited by (understandably) anti-German wartime military censors only initially appeared in 1943.

What is certain, however, is that Patton never read this excellent, insightful, and revealing new English translation—which is much truer and exceedingly more faithful to Rommel’s highly nuanced, original German account than the extremely poor, indifferently translated wartime 1943 and 1944 English editions. Comparing Zita Steele’s (pen name of award-winning writer-historian-editor, Zita Ballinger Fletcher) brilliant new translation of Rommel’s classic book is akin to comparing Shakespeare’s Hamlet to a fourth-grade “Dick and Jane” grammar book. Steele’s deft translation finally does justice to Rommel’s original German text.

Bringing the Original Text To Life

Rommel’s original text comes vividly alive through Steele’s superb German-to-English translation and his account of how he reacted to and developed his innovative small-unit tactics to consistently defeat the forces arrayed against his own unit is exceptionally well-revealed in her new book. Usually outnumbered and outgunned, German mountain ranger assault troops under the young Rommel, time and time again overcame their enemies’ superior numbers and greater firepower to achieve their often daunting objectives. Steele consistently, and much more correctly, translates “German alpine troops” as “mountain rangers,” thereby better capturing the true nature of these, in effect, early versions of what would eventually be known as “special operations forces”.

Rommel describes how and why he developed the tactics he used to prevail in each engagement, revealing his constant development as an innovative troop leader. This excellent new translation traces the gradual but proceeding development during combat in France and in the mountains of the Eastern Front of the young Rommel whose later operational genius would suddenly burst forth upon the Belgian, French and North African battlefields of World War II. This translation demonstrates the roots of Rommel’s operational genius, showing “how Rommel became Rommel.”

Rommel As A Person

Steele also reveals Erwin Rommel as a person, with the all-too-human flaws he possessed. Although the enduring image of Rommel was that of a homebody “family” man, a devoted, doting husband to his wife Lucie (they married in 1916), his relationship with another woman produced an illegitimate daughter, Gertrud, in 1913, whom he manfully acknowledged and for whom he provided financial support.

Additionally, Steele presents a convincing argument—based on Rommel’s admitted life-long insomnia and recurrent nightmares—that he suffered from PTSD, post traumatic stress disorder. Given his WWI wounds, the nightmarish combat he endured in that war, and the loss of many close friends, that diagnosis seems completely credible. Coincidentally, Patton’s best biographer, Carlo D’Este, concludes—very convincingly—that Patton also suffered from PTSD. This reviewer strongly concurs with both authors’ “diagnoses.”

Was Rommel A Nazi?

Steele also delves into THE question involving Rommel: Was he or was he not a “Nazi?” Although it is a historical fact that Erwin Rommel was never a member of the Nazi Party, his promotions by Adolf Hitler always beg the question of was Rommel a “secret” Nazi, whether an official member of the Party or not? Steele concludes—correctly in this reviewer’s opinion—that Rommel was definitely not a Nazi. Clearly, Rommel personally benefited from Hitler’s support and indulgences, but so did other non-Nazis if they served Hitler’s interests when that service was beneficial to the Nazi dictator. Rommel was enough of a non-Nazi that he paid the ultimate price—Hitler’s toadies forced the field marshal to commit suicide on Oct. 14, 1944 in the wake of the July 20, 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler of which Rommel knew but of which he was not an integral part.

Zita Steele’s new book which is based on her new, insightful, nuanced and authoritative English translation of Erwin Rommel’s classic of military history 1937 book, Infantry Attacks, is a hands’-down, “must-have” book in any military history enthusiast’s library. It not only makes earlier English translations of Rommel’s book obsolete, it’s a “classic” account of World War I combat. Above all, it’s an insightful preview of one of the most famous commanders of World War II—and how he learned his trade! Buy it! Read it! Enjoy it!

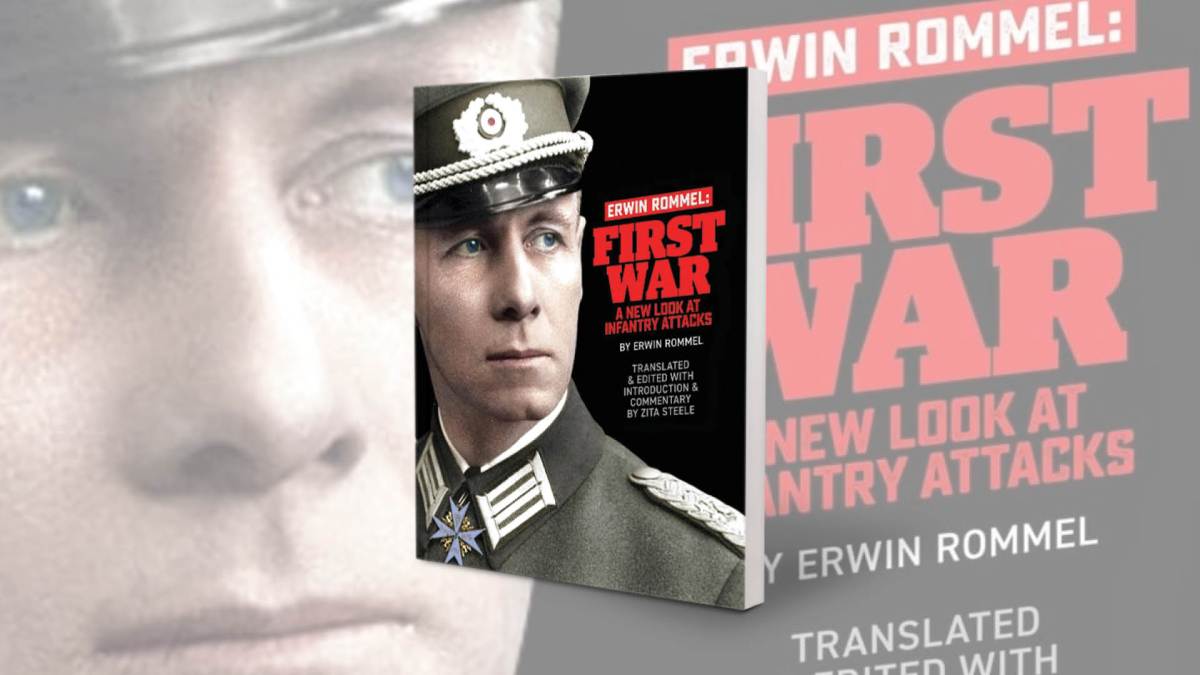

ERwin Rommel: First War

A New Look At Infantry Attacks

By Zita Steele

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.