The Bay Area port city recalls an era of can-do American spirit.

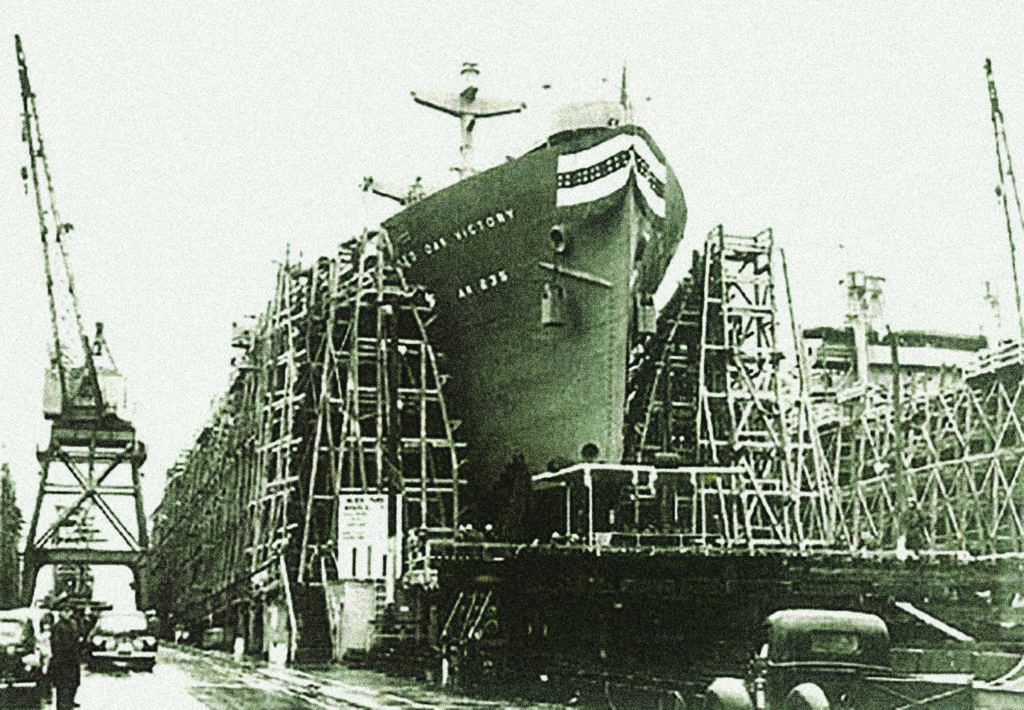

I stroll alongside the SS Red Oak Victory, a World War II ammunition vessel being restored in California’s Richmond harbor, trying to wrap my head around its history, what it represents. Its great hull towers above me, with giant welded plates measuring 455 feet in length. It is the last surviving Victory ship built in Richmond’s shipyard during the war, one of 747 ships of all types manufactured here between 1940 and 1945 at top speed—in its case, 88 days from start to finish. Indeed, Richmond sent more ships to the world’s wartime theaters than any other shipyard in America.

That’s why, it’s said, Hitler was aware of Richmond, California. As was Hideki Tojo, along with Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill, and, of course, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Anyone familiar with today’s quiet, unassuming community on San Francisco Bay’s northern end might find that hard to believe. But back in its day, Richmond was a hub of frenetic wartime activity, as brand-new ships slipped into the bay amid blaring loudspeakers, exuberant brass bands, shattering champagne bottles, and celebratory cheers from many of the shipyard’s 90,000 employees. The gritty city was home to 56 different war industries, including bomb production and homebuilding for the upsurge of shipyard workers.

But the Red Oak represents much more, as I learn during my recent visit to the Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park, where the ship is being preserved as a museum. Established in 2000 at Richmond’s historic Kaiser Shipyards, the park encompasses several scattered sites that showcase home-front contributions during World War II.

I begin my visit at the park’s hub, a visitor education center housed in the former oil house, where vats of oil that fueled the adjacent Ford Assembly Plant’s tank production were kept. Today, the brick building holds interactive exhibits—including a rivet station, welding gear, and oral histories—that provide an excellent overview of the region’s World War II home-front story. I read about Henry J. Kaiser, the maverick industrialist responsible for building Richmond’s four shipyards in the first place, who introduced groundbreaking mass-production methods that maximized prefabricated and electric-arc welding techniques. The founder of more than 100 companies (including one that built Nevada’s Hoover Dam), Kaiser had never before built a ship, but he didn’t let that stop him: “A ship is just a building that floats,” he reportedly said. I also get a glimpse into wartime Richmond, how this little city exploded in population during those years, and businesses supporting the shipbuilding worked around the clock. I learn about how, in an era still very segregated, Kaiser hired African American workers from the South—though only in low-level positions.

And I delve into the stories of the women who flooded to Richmond’s shipping industry, working in wartime jobs previously reserved for men. Dubbed across the nation as “Rosie the Riveters”—popularized in a 1942 song praising female assembly-line workers and later made iconic by the famous “We Can Do It!” poster—Richmond’s women workers weren’t in fact riveters, since Kaiser’s new method of ship construction used welding over riveting. They were really “Wendy the Welders,” along with machinists, drivers, shipfitters, electricians, carpenters, and all kinds of other workers.

I’m captivated by the words of former Rosies (er, Wendys) sprinkled throughout the exhibits. Among one of the welders is Kay Morrison. “I could weld anything anywhere, flat, vertical, overhead, whatever was needed,” she says in one of the videos. She spent two-and-a-half years in Kaiser’s Yard Two, working the graveyard shift.

But it’s in the basement where Richmond’s eclectic wartime stories truly come alive, through films, lectures, and storytelling. I watch a documentary detailing the disturbing story of local Japanese American immigrants who had made good lives for themselves growing and selling cut flowers. “Here in Richmond, I felt, being the son of an immigrant, being in business, I felt that I was as good as the next man,” states Tom Oishi in the film.

All that came crashing down with FDR’s Executive Order 9066 of 1942, forcing Japanese Americans living on the West Coast to be moved to wartime “relocation centers” farther inland. Most of the families found their flower nurseries and homes destroyed upon their return after the war—though that didn’t stop them from starting over, bringing the flower business back to Richmond in the postwar years.

But most riveting is listening to Betty Reid Soskin, the spirited, 98-year-old park ranger (the oldest in the National Park Service system), who a couple times a week shares her personal story as a young African American in the Richmond shipyards during World War II.

“Rosie the Riveter was a white woman’s story,” she tells a room of 50 or so people. “There were no black Rosies. Segregation still prevailed in California in the 1940s, and blacks were forced to work menial jobs.”

As such, she worked as a file clerk in a segregated union hall. Although she technically was part of the shipbuilding process, she never once saw the fanfare that came with launching one of the great war ships. Betty recalls, “I stood at my window, [processing] the change of addresses of those who lined up. I really assumed that all the ship workers were black, because that’s all who I saw come to my window.”

Betty emphasizes that Richmond’s World War II history—and the home front in general—doesn’t embrace one single story. It’s the “African Americans who were sharecroppers who came out of the South to answer the call for workers,” she says, adding, “but also the Japanese Americans who were interned, and the Port of Chicago [California] workers who were killed [in the largest industrial accident on the home front, when an ammunition ship exploded on July 17, 1944, killing 320 mainly black sailors].”

And that’s the crux of it all. There’s not one Rosie. There are many different Rosies, and many different non-Rosies—all essential parts of the overall home-front narrative.

With this in mind, I visit the other sites under the park’s auspices, which are scattered about Richmond, some in disrepair. Next to the visitor center rises the Ford Assembly Plant, designed in the late 1920s by esteemed industrial architect Albert Kahn. The West Coast’s largest assembly plant, it churned out 49,000 jeeps and processed 91,000 other military vehicles during the course of the war. Today the beautifully restored building hosts community special events. Meanwhile, the dilapidated Kaiser Richmond Field Hospital on Cutting Boulevard recalls Kaiser’s revolutionary medical care system for shipyard workers, in which workers paid a nominal price on a prepaid basis (at a time when only nine percent of Americans had health insurance). Nearby, the Maritime Child Development Center on Florida Avenue provided childcare for the shipyard’s working women; there’s a small exhibit in the back (reservations required). There’s also the shipyard’s abandoned employee cafeteria and first-aid station on Canal Boulevard, as well as Atchison Village, a neighborhood in western Richmond of small, wood-frame houses, now privately owned, that once served as wartime worker housing. And a path along the bayfront leads from the visitor center to Rosie the Riveter Memorial Park, on the spot where Kaiser’s Yard Two once operated. A sculpture evokes a ship under construction and includes pictures and recollections from Rosies arranged along a walkway measuring the length of a ship’s keel.

And then there’s the Red Oak itself. Today the ship sits on the site of historic Yard Three, its prow pointing into the bay as if ready to leap into action again. It’s open as a museum, alongside a giant revolving crane that once moved prefabricated sections onto the ship hulls.

The fact crystallizes in my mind that this impressive ship represents an entire era of American spirit encompassing the burgeoning notions of equal rights, fair employment, affordable housing, around-the-clock childcare, food service, and healthcare—all kudos to the foresight of Henry Kaiser in his groundbreaking business model. But it’s not as simple as that. We talk about the war as a unifier, but a visit to the park showcases the fact that, while some equality was achieved, there were lots of bridges that had to be built. And then the war ended.

As the servicemen returned home, the women and African Americans were the first to lose their jobs and the benefits that had been inspired by wartime necessity. Despite this, I leave the park feeling positive, for I see how advances made in the workplace during the war had planted a seed for the civil rights progress yet to come. The park remains an important place to continue talking about these issues—and ensures that the “We can do it!” optimism will not die.

WHEN YOU GO

Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park is located about 20 miles north of San Francisco. From San Francisco or Oakland airports, you will need to rent a car and head up I-80 to reach Richmond.

Entry to the visitor center, films, and lectures is free. Real-life Rosies are on-hand most Fridays. Some of the sites are open on abbreviated schedules, including the SS Red Oak Victory which charges fees for tours.

Check the website for upcoming events. Note that Betty Reid Soskin’s popular presentations are on hold while she recovers from a recent stroke.

Where to Stay and Eat

The best place to stay is in nearby Berkeley, which has plenty of hotels and restaurants. The Assemble restaurant next to the visitor education center serves up American classics in a historic setting. The Riggers Loft Wine Company, across the parking lot from SS Red Oak Victory, is in a former shipbuilding warehouse on the water and serves housemade wines and ciders.

What Else to See and Do

The National Park Service’s “World War II in the San Francisco Bay Area” itinerary brings together various regional sites related to World War II history, including several local forts and the Presidio in San Francisco.

This article was published in the February 2020 issue of World War II.