A bare-bones biplane served as a faithful beast of burden and potent psyops weapon in two wars.

At 3 a.m. on November 28, 1950, troops at Pyongyang airfield in northwestern Korea heard the sputtering engine of an intruder overhead. A tiny plane flew low and slow over the 8th Fighter-Bomber Group’s parking ramp, dropping a string of fragmentation bombs on a row of North American F-51D Mustangs. Three of the 11 aircraft hit had to be junked. During a subsequent incident in June 1951, two more night intruders struck Suwon airfield, killing an American officer and wounding five airmen. In addition, one of the 335th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron’s North American F-86 Sabres was completely gutted by fire and eight others damaged, four seriously.

Amazingly enough in the first war of the Jet Age, the nighttime raiders were open-cockpit Polikarpov Po-2 biplanes that had been supplied to North Korea by the Soviet Union. The Americans dubbed the flying anachronisms “Bed-Check Charlies,” due to their frequent nocturnal visits to allied positions. The Po-2’s tactical role in Korea actually hearkened back to World War II, when the Soviets had successfully employed them as nighttime nuisance raiders, famously equipping an all-woman regiment with the already obsolete airplane to combat German invaders.

UN forces in Korea soon realized the Po-2s would be far more difficult to pick off than expected. The ground-hugging planes proved hard to track by radar, thanks to their canvas and wood construction, and attempts to chase them down with high-speed jets could be dangerous. In May 1953, for example, a Lockheed F-94B managed to down a Po-2, but crashed in the process. Investigators determined that the Starfire pilot must have throttled back to keep the lumbering, low-flying intruder in his sights, then stalled without enough altitude to recover. The allies concluded that in order to pursue the Po-2s they would have to specially modify propeller planes, such as Vought F4U-4 Corsairs and Douglas AD Skyraiders, equipping them with belly radomes. Given the small amount of damage generally done by the nuisance raiders, it seemed an expensive solution.

The Po-2 emerged from the drawing board more than two decades before the Korean War. It was the brainchild of gifted Russian designer Nikolai Nikolaevich Polikarpov, a 1916 graduate of the St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute who initially worked under Igor I. Sikorsky. Over a 22-year period, Polikarpov would create some 40 aircraft, but the one that earned him lasting fame had extremely modest beginnings.

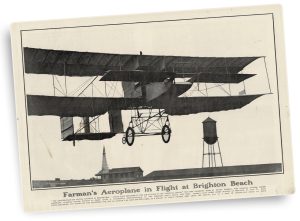

Polikarpov originally designed his dumpy little biplane as a trainer that could also be used for scouting. The first version in 1927 was a failure, with wings that were too thick and a disappointing rate of climb. Soviet authorities sent Polikarpov back to the drawing board, and a year later he came up with a winner. Slow, cheap to build and very forgiving, the little aircraft impressed everyone with its handling. Originally known as the U-2 (later renamed Po-2), the trainer had one feature that was novel for its day—static longitudinal stability. Test pilots found they had to work hard to send it into a spin, and even then they only had to release or center the stick to pull it out.

The open-cockpit two-seater was powered by a reliable 5-cylinder Shvetsov 100-hp air-cooled radial engine that gave it a maximum speed of 93 mph (carrying a full bombload, it could barely reach 60 mph). The design was basic to the point of austerity; it even lacked a radio. But the U-2 could be flown from grass or dirt runways, required little room for takeoff and could land at 40 mph in very tight quarters. That came in handy during WWII, when the Soviets needed a rugged plane capable of supplying partisans behind the lines. And thanks to a configuration reminiscent of World War I fighters, the U-2 could turn on a dime—a characteristic that would frustrate Luftwaffe pilots.

Polikarpov could never have imagined how versatile his ugly duckling would become. It was fitted with skis, then turned into a cropduster by moving the front seat forward and mounting a tank for chemicals behind. Next came a seaplane version with wingtip floats. It seemed there was no end to how many variations could be dreamed up.

Unfortunately for Polikarpov, Josef Stalin intervened at this point. Perhaps because Polikarpov had traveled abroad in the 1920s, studying aircraft industries in Britain, France and Germany, the xenophobic premier had the designer accused of treason in 1929. Polikarpov and other engineers were sent to prison and continued their work under armed guard. Ultimately the prisons held about 300 of the nation’s top specialists in science and aviation. Polikarpov was released after two years because he designed an outstanding fighter, the I-15, which saw action in the Spanish Civil War.

In the meantime, his homely U-2’s career continued to blossom. No less than 30 variations were ultimately created. One was a three-seater air taxi, also used for aerial survey. Another, called sanitarni (ambulance), had room for a pilot, stretcher and medical attendant and played a prominent role in developing the Soviet health service across the nation’s vast rural areas. The little biplane was also adapted for transport, forestry patrol and arctic service.

World War II saw the U-2 fulfill its most celebrated role, as a close support aircraft. In the standard configuration it could carry a bombload of up to 660 pounds and was equipped with a 7.62mm rear-facing machine gun. Another variant carried a lighter bombload but packed four 82mm rockets under its wings. Still others were used for artillery correction at night and for psychological warfare, modified to include a transmitter and loudspeaker.

But the mission that brought the U-2 lasting fame had its genesis when the Russians organized an entire regiment of women pilots to attack German targets at night. Called Nächthexen, or “Night Witches,” by the Germans, these fearless, skillful fliers displayed magnificent endurance in the course of countless grueling sorties.

The idea of women pilots was not actually new in Russia at that point. When World War I began in 1914, Princess Evgenie Shakhovskaya had asked Tsar Nicholas II if she could become a military pilot. She ended up making reconnaissance flights. Aleksandr Keren – sky’s government later gave permission for women to join the Russian army, and a number of them followed Princess Evgenie’s example.

The Great Patriotic War, as WWII was known in the Soviet Union, catapulted Russian women into the role of fighter-bomber pilots. With German panzers at the gates of Moscow in 1941, the Soviets were desperate for any means to stop them. Stalin summoned Major Marina Raskova to form the all-female 122nd Aviation Group, which was to include the 588th Night Bomber Regiment, flying converted U-2 trainers. The first woman to become a navigator in the Soviet air force, Raskova was already a folk heroine in Russia.

By the spring of 1942, the new regiment was trained and ready for combat. It began operations along the Don River, attacking bridges, enemy fuel and ammunition dumps and troop concentrations. But its greatest challenge came six months later at Stalingrad. Avoiding daylight sorties, when the biplane would have been easy prey for Luftwaffe fighters, the Russians sent U-2s over after dark at frequent intervals to drop fragmentation bombs, harassing Wehrmacht troops.

Stalin’s secret police interrogators had learned long before WWII that sleep deprivation could be used to break down the morale of political prisoners. The army put that knowledge to work via the U-2, effectively making nightly bombing raids an instrument of psychological warfare. The tiny biplanes continuously shuttled back and forth over the front lines, on bombing missions as little as three minutes apart, keeping the Germans on edge all night long. Flying their open-cockpit planes at night over the burning city, the Russian women—pilot in the front cockpit, navigator to the rear—came to be dreaded by the weary Germans.

The Wehrmacht troops complained bitterly about the raids. German Lt. Gen. Walter Schwabedissen recalled that although the little aircraft did only minor damage, the near-continuous low-level bombing inflicted acute psychological strain on his troops. Right up to the end of the war, Schwabedissen said, the Germans searched unsuccessfully for an effective weapon against the nocturnal pests.

It is hard to fully appreciate today the price the Night Witches paid for their contribution to the war. The U-2s provided scant shelter from rain, snow and extreme cold. Lacking bombsights, the pilots used a chalk mark on one wing to line up targets. They tossed flares by hand out of their cockpits, often forced in freezing weather to unscrew the safety pins with bare fingers, which tended to stick to the metal components. The bombs they carried were supposed to be released by a jury-rigged wire, but whenever that contraption failed to work, the navigator had to climb out on a wing, like some daredevil stuntman, and release the bomb by hand. Incredibly, the government did not issue parachutes to the women until 1944.

Life for the female ground crews was also difficult as well as hazardous. Since a single plane might undertake 10 or more sorties each night, crews were kept busy crawling over and under just-returned aircraft, refueling them and reloading them by flashlight—and sometimes forced to work in total darkness if German fighters were nearby.

The “ladies,” as the Germans sometimes called them, had to be resourceful just to keep their obsolete planes in the air. In 1942, for example, with the Germans advancing rapidly and both the Soviet army and the U-2 regiment in retreat, one pilot knocked off part of her wooden propeller in a hasty landing. When enemy tanks threatened the airfield and the squadron was ordered to scramble, Senior Lt. Nina Raspopova had to make a quick decision. She asked the ground crew to cut off an equal amount from the opposite end of the prop to reduce vibration. She then managed to get her damaged crate back up into the air, but it was shaking so violently that she had to hold onto the stick with both hands until she could land at another field.

The U-2 had duplicate controls in the cockpits, a leftover from trainer days that could assume vital importance in combat. On one occasion, navigator Ira Kasherina discovered the pilot sitting in front of her had been killed by flak and was slumped over, jamming the controls. Reaching forward and grabbing the pilot’s collar, she pulled the body back, freeing the stick, then somehow maneuvered the plane back to base using only one hand. For her feat she was awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

In honor of 588th Regiment’s achievements, in 1943 the unit was renamed the 46th Guards Night Bomber Regiment. By the end of the war, Po-2 pilots had flown more than 23,000 sorties and dropped some 3,000 tons of bombs. Thirty aircrew members were killed in action, and 23 were awarded the Gold Star of a Hero of the Soviet Union, five of them posthumously.

Given the Night Witches’ notable success against the Germans with the Po-2, it’s understandable that Communist forces adopted the biplanes for a similar role a few years later during the Korean War. North Korea had about 20 of the obsolete aircraft on hand at the conflict’s outset, some of which were destroyed in UN attacks. But after the Soviet Union supplied an additional shipment of Po-2s, the Korean People’s Air Force began employing them for nuisance raids in November 1950. Because of the damage done by the Bed-Check Charlies, UN forces were forced to devote considerable resources to intercept a handful of elderly biplanes.

As for the plane’s creator, Nikolai Polikarpov, he eventually fell into disfavor with Stalin because some of the other aircraft he designed were deemed failures. But when the 52-year-old designer died of cancer on July 30, 1944, Soviet authorities renamed the U-2 the Po-2 in his honor. Considering his little biplane’s versatility as well as its longevity, its designer achieved a measure of immortality that would likely have amazed him.

In time, the Po-2 set a record for a basic design: A grand total of some 40,000 were produced—a record exceeded only by the Cessna 172 (43,000 and still counting). The Soviet Union built Po-2s from 1928 to 1951, and Poland turned them out under license from 1948 to 1955. But that was not the end of it. Numerous aeroclubs and enthusiasts kept constructing them in Russia until 1959.

There are a handful of Po-2s that are still flying today, with some advertised for sale on the Internet at five figures and up. One 1954 model that had been restored for a traveling exhibition recently listed at $125,000.

Truman Temple, who worked as a newpaper reporter for 20 years, recommends for further reading: Night Witches: The Untold Story of Soviet Women in Combat, by Bruce Myles; and A Dance With Death: Soviet Airwomen in World War II, by Anne Noggle.

Originally published in the November 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.