At 6 o’clock on the evening of June 24, 1919, a train pulled into the small town of Romanovka, Russia. When the cars came to a halt, 33-year-old Lt. Col. Robert L. Eichelberger stepped lightly onto the station platform. The U.S. Army intelligence officer was en route from Vladivostok to Suchan (present-day Partizansk), a coal mining hub some 35 miles farther east as the crow flies. Eichelberger would later serve with distinction under General of the Army Douglas MacArthur in the Pacific theater of World War II. But on that warm, still evening seven months after the end of World War I he’d been sent to negotiate the release of five American soldiers taken captive while fishing along the Suchan River and to investigate why U.S. troops in the region had been suffering frequent attacks by Bolsheviks—the communist followers of Soviet Chairman Vladimir Lenin then engaged in a brutal civil war against monarchist supporters of the executed czar, Nicholas II.

Though Eichelberger found Romanovka generally quiet the evening of his visit, the next day it was the scene of a bloody fight some historians consider the last battle of World War I.

The Allies sent troops into Russia in the fall of 1918 to secure the thousands of tons of arms, munitions and other war materiel provided to imperial Russia before the communist revolution that deposed Nicholas in March 1917. Troops from a dozen nations—including the United States, France, Britain, Italy and Japan—occupied ports and other strategic facilities across the embattled country, primarily in the northern European region, the far eastern Pacific and Siberia. The 5,000 soldiers of the American North Russia Expeditionary Force (aka “Polar Bears”) were sent to help secure the port of Archangel, while the 8,000 men of the American Expeditionary Force, Siberia were dispatched to the port of Vladivostok, in the far east.

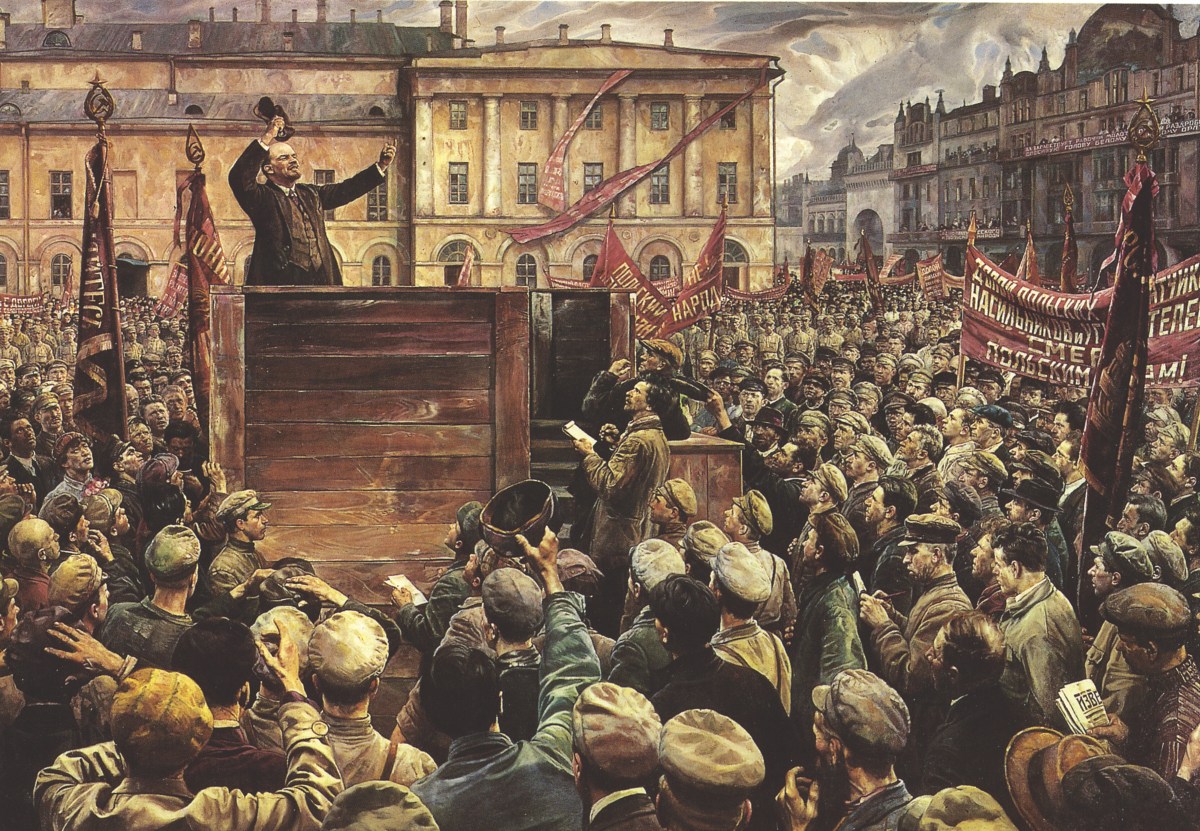

The American forces arrived in Russia 60 to 90 days before the signing of the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918. Though the Allies’ reasons for being in Russia ostensibly disappeared when the war ended, the subsequent failure of the moderate government of Alexander Kerensky and later seizure of power by Lenin and his radical Bolsheviks prompted the interventionist nations to maintain their in-country military presence. They also chose to abandon their professed neutrality and militarily support the anti-communist White Army forces in the civil war that engulfed Russia following Kerensky’s downfall. That choice inevitably brought Allied troops into direct combat with Bolshevik Red Army regulars and partisans.

Among the units dispatched to Siberia was the 31st U.S. Infantry Regiment out of Fort William McKinley, just outside Manila in the Philippines. On arrival in Russia the regiment’s three battalions were tasked with securing Vladivostok, sections of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the branch line leading from Vladivostok to the vital coal mines in Suchan. The latter duty was the responsibility of the regiment’s 1st Battalion, whose Company A was deployed in and around Romanovka.

When Eichelberger and Maj. Sidney C. Graves, son of Siberian expedition commander Maj. Gen. William Sidney Graves, stopped in Romanovka that June 24, they were less than pleased with Company A’s combat readiness. As Eichelberger wrote to wife Emma the next day:

When passing through Romanovka at 6 p.m., we found an American platoon with camp pitched on the village green (men bathing and playing baseball, etc.). We met a young West Pointer who was in command. Sidney remarked to me he should have some trenches constructed for use in case of attack.

The West Pointer was 21-year-old 2nd Lt. Harry Krieger, a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy’s accelerated Class of 1918. But he would not retain command for long. Earlier on the 24th one of Company A’s platoons had left Romanovka, bound for Company C’s command post in Kangaus (present-day Anisimovka), 20 miles to the east. That left Krieger with 51 men of Company A’s 3rd Platoon to guard the railroad and a nearby bridge. At dusk 27-year-old 2nd Lt. Lawrence D. Butler arrived with 21 reinforcements. As there had been friction between the people of Romanovka and Krieger, Butler was placed in charge of the combined American force.

Despite the regional uptick in Bolshevik attacks, Romanovka appeared peaceful. The Yanks and villagers mingled on a daily basis and seemed to tolerate one another. There was even a romance blooming, as Sgt. Almus Beck of Company C had won the heart of a resident Polish nurse named Lillie who had lately served in the White Army. Beck had left with Company C on the morning of the 24th, while Lillie remained in town.

She would soon have reason to put her considerable nursing skills to work.

The Americans encamped in Romanovka may have felt relatively secure the night of June 24, but by dawn the following morning some 200 Red Army soldiers had massed along a bluff overlooking town. Led by a fiery Moldovan-born Bolshevik leader named Sergei Lazo, the Russians were bent on inflicting as many casualties as possible on the troops they viewed as foreign invaders.

The Reds launched their attack at 5 a.m. as the lone American sentry left his nighttime post, unrelieved, to come in for breakfast. Firing from the hilltop, the attackers raked the American tents were machine-gun and rifle fire, killing or wounding many men while they slept. Among those seriously injured was Butler. Shot through the jaw, bleeding badly and unable to speak, he still managed to organize the bewildered doughboys. Recognizing the peril his men faced if they remained in the open, he used hand gestures and hastily scrawled notes to direct the survivors toward a trio of log houses on the outskirts of town. (For his actions Butler would ultimately receive the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second-highest award for combat valor, behind the Medal of Honor.)

That fall the International News Service distributed the lieutenant’s summary account of the attack:

Most of the boys who were killed never had a chance to leave their beds.…They were shot while asleep. The others came scrambling out and fought in their underclothing. I ordered them on to advance in skirmish order. They moved as though on the drill ground. A corporal, already wounded in the foot, led them. He walked, and the men followed.…

My orderly was behind me, carrying my rifle. My pistol was empty, and I turned to him, asking for the rifle. As he handed it to me, his head was blown off. I was wounded in the leg by an American bullet fired by a Russian.

A Russian ran to our ammunition tent. I put my head out of a window in a house where I had gone to pick a sharpshooter and received a bullet in the jaw. My teeth flew over the place like so many pellets.

Inspired by Butler’s valor, heroes began to emerge. Covering the survivors’ retreat across open ground were three sharpshooters—Pvts. Roy Jones and Emmet Lunsford, each armed with a Browning automatic rifle (BAR), and Pvt. George Strakey, with his fast-firing single-shot M1903 Springfield rifle. Though wounded, all three continued to expose themselves to fire for clear shots at the enemy. (Each would recover from his wounds and receive a Distinguished Service Cross.)

After gaining the protection of the log houses, the lieutenant called for volunteers to sprint back across open ground to the railroad tracks and follow them 6 miles east to summon help from Company E in Novonezhino. Corporals Leo Heinzman and Valeryan Brodnicki responded, each taking a different path in the hope at least one would get through. All able-bodied men provided covering fire. Although Brodnicki was twice hit by Bolshevik bullets, both men made it to the tracks. Heinzman soon flagged down an inbound train from Novonezhino. Aboard it were Sgt. Sylvester Moore and a 17-man detachment from Company K. Realizing they were too few to make a difference, Moore had the engineer back the train to Novonezhino to alert Company E. The train stopped only to pick up the wounded Brodnicki. (He and Heinzman would later both receive the Distinguished Service Cross.)

In Novonezhino the pair waited as Lt. Lewis J. Lorimar organized a relief mission. When the train set out again, 77 soldiers were aboard—58 from Company E, the 17 from Company K and Butler’s two courageous runners. Before dispatching the relief force, Lorimar also ordered a hospital train from Kangaus to come to the aid of the besieged men in Romanovka.

Meanwhile, from their barricaded stronghold within the log houses the Americans used BARs, rifles and grenades to keep the encroaching Bolsheviks at bay. Inside, however, several wounded and dying men needed immediate attention. The only medic in the detachment, Pvt. Herbert Naylor, had been grievously wounded early that morning and would die four days later in hospital. Fortunately, Sgt. Beck’s flame, Lillie the Polish nurse, was there to help. While the sights, sounds and smells would have unnerved even an experienced combat nurse, she retrieved wounded from the field, staunched bleeding, bandaged wounds and comforted the dying with compassion and skill. In after-action reports the survivors also praised another village woman, who patched up the lightly wounded and helped where she could as her three wide-eyed children looked on.

The train carrying Lorimar’s heavily armed relief force was the first to arrive in Romanovka, and it prompted the Bolsheviks to begin pulling out. The disembarking Americans were stunned by the carnage they found. The camp was a scene of devastation, and trails of blood led from the tents to the three barricaded log houses. “The ground was strewn with blood-soaked bodies of American soldiers,” 2nd Lt. Sylvian Kindall recalled. “Splintered bones and flesh torn with ghastly holes told plainly that dumdum bullets had been used. Half of those hit were dead; others were dying or were too injured to rise from the ground.”

While the fighting was largely over, the withdrawing Reds did leave a few snipers to keep the Americans’ heads down. That remained a concern once the hospital train arrived and disembarking medics began tending the wounded and gathering the dead. Capt. Oscar C. Frundt was in charge of the train. He triaged cases and supervised the loading of patients for the arduous trip back to Vladivostok, all while under fire. Once aboard he ensured their wounds were dressed and approved sulfate and morphine for the worst cases. He also took pains to ensure there was plenty of hot coffee and crackers on hand for those who could eat. (Frundt would also receive the Distinguished Service Cross.)

But the day’s agonies were not over. A bridge between Romanovka and the main Trans-Siberian line to Vladivostok had been destroyed, so the injured and dead had to be transferred across a river gorge to another train. Frundt’s staff removed the wounded from the hospital train on litters, carried them as gently as possible over a footbridge and loaded them onto a waiting Vladivostok-bound freight train—the wounded on two open boxcars, the dead on a third. During the onward journey the freight cars rattled and bumped all the way.

When the train pulled into Vladivostok at 7 p.m. that night, U.S. Army medical personnel from Evacuation Hospital No. 17 did their best to settle the patients and care for the dead. As Sgt. Sam Richardson recalled, hospital staff worked through the night administering medicine, tending wounds and embalming the dead. Richardson was tasked with compiling a casualty list to notify officials and next of kin back in the United States. His tally recorded 19 killed and 26 wounded, five of whom would die from their wounds. More than 60 percent of the Americans in camp that day had fallen as casualties.

The end of the Romanovka battle marked the beginning of a long road to recovery for the American wounded. After initial care at the evacuation hospital in Vladivostok, Butler and a dozen others were deemed fit to be moved. On August 4 they embarked on the USAT Sherman, bound for San Francisco. It was not a pleasant voyage. Soon after stopping to refuel in Manila, the ship ran into a typhoon. The San Francisco Chronicle reported the consequences:

The transport lost her wireless plant in a typhoon four days out of Manila that…taxed the seaworthiness of the ship to the utmost. For 20 hours the wind maintained a velocity of 120 miles an hour. Nearly everyone on board was sick, and the troops in the hold of the vessel, where they were denied fresh air owing to the fact that the hatches everywhere had to be closed, suffered intensely but without complaint.

Adding to the misery aboard ship was an outbreak of cholera, necessitating a 16-day quarantine for those aboard when the vessel reached Nagasaki, Japan.

Sherman finally arrived in San Francisco on October 9, more than two months after having left Vladivostok. Butler and the other Romanovka wounded were taken to the Letterman Army Hospital at the Presidio, where the young lieutenant began a round of reconstructive surgeries. In the meantime, whenever he craved a smoke, a handkerchief tied atop his head and looped beneath his shattered jaw sufficed as a lower lip.

In January 1920 the 27th and 31st infantry regiments began a gradual withdrawal, recalling their far-flung units to the vicinity of Vladivostok. On April Fools’ Day the last elements of the American Expeditionary Force, Siberia sailed from Vladivostok. While the value of the campaign has never been established, the final cost to Company A on June 25, 1919—24 dead and 21 wounded—seems a steep price to have paid for securing arms and materiel. Adding the estimated dozens of Bolshevik dead only magnifies the futility of the battle, the campaign and, in many ways, World War I itself.

Robert L. Willett is the author of three histories, including The Russian Sideshow: America’s Undeclared War, 1918–1920. For further reading he also recommends When the United States Invaded Russia, by Carl J. Richard.